Полная версия

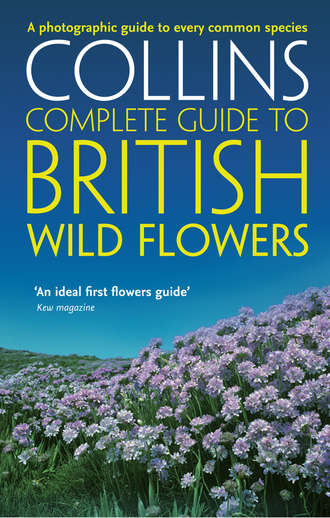

British Wild Flowers: A photographic guide to every common species

LOUSEWORTS AND COW-WHEATS – flowers 2-lipped; upper lip hooded, lower lip 3-lobed; borne in spike-like heads in most species; pinkish or purple depending on species; see pp.

FUMITORIES – flowers 2-lipped; pinkish or yellow depending on species; see pp.

FIGWORTS – flowers tiny, globular and 2-lipped; upper lip 2-lobed, lower lip 3-lobed; purplish or yellow depending on species; see pp.

LABIATES – flowers 2-lipped; lower lip often lobed, upper lip often hooded and toothed; borne in spikes in most species; whole plant often aromatic; wide range of colours seen in the different species; see pp.

BROOMRAPES – flowers 2-lipped; upper lip hooded, lower lip 3-lobed; flowers the same colour as rest of plant; borne in spikes; see pp.

MANY-FLOWERED HEADS OR FLOWERS IN CLUSTERED HEADS

UMBELLIFERS OR CARROT FAMILY MEMBERS – individual flowers comprising 5 tiny petals; flowers stalked and arranged in umbrella-shaped heads; white or yellow depending on species; see pp.

SCABIOUSES – individual flowers with 4 or 5 petals depending on species; borne in dense, domed heads; outer flowers often larger than inner ones; see pp.

DAISY FAMILY MEMBERS – numerous tiny flowers; arranged in dense heads in most species; inner disc florets appearing very different from outer ray florets in many species; wide range of colours seen in the different species; see pp.

FRUITS AND SEEDS

FRUITS FOLLOW IN THE wake of flowers and are the structures in which a plant’s seeds develop and are protected. In many cases, the shape and structure of these fruits, and often the seeds themselves, are designed to assist their dispersal, when ripe, away from the plant that produced them. A number of ingenious methods have evolved to facilitate this process: some seeds are carried by the wind; others attach themselves to the fur of animals; some even float away on water or have evolved to be eaten and digested by birds. The study of fruits and seeds is not only fascinating in its own right but in many instances the structure or appearance of a fruit can be a valuable aid to correct identification.

The burred fruits of Lesser Burdock readily become snagged in animal fur, travelling with the creature until the fruit finally disintegrates and liberates the seeds.

The hook-tipped spines on the fruit of Wood Avens catch in animal fur. Subsequently, they also help the fruit to disintegrate, as unattached barbs snag on objects and material that the animal rubs against.

The flowers of Common and Grey Field-speedwells are rather similar. Only by looking at the fruits (Common left, Grey right) can you be absolutely certain of any given plant’s identity.

Cabbage family members produce fruits known as pods, which vary considerably in terms of size and shape according to species. Those of Wild Candytuft, seen here, are particularly attractive.

Dandelion seeds are armed with a tuft of hairs – the pappus – that assists wind dispersal. While it remains intact, the collection of seeds and hairs is often referred to as a ‘clock’.

The fruits of Field Gromwell are hard-cased nutlets, designed to be resistant to abrasion and wear, allowing the species to grow as an arable weed, but of course only in the absence of herbicides.

Like other members of the pea family, the fruits of bird’s-foottrefoil are elongated pods.

The seeds of Elder are contained within luscious berries. These are eaten by birds and the seeds (protected by a coating resistant to being digested) are dispersed with the droppings.

The fruits of roses are fleshy and known as hips; inside these are seeds (dry achenes).

The fruit of the Common Poppy is a hollow vessel that contains thousands of minute seeds. When the fruit is ripe, holes below its rim allow seeds to escape when the plant is shaken by the wind.

In strict botanical terms, the fruits of the Raspberry are a collection of small drupes – each one a fleshy fruit that contains a hard-coated seed.

LEAVES

BEING THE MAIN STRUCTURES responsible for photosynthesis, a plant’s leaves are its powerhouse. They vary from species to species and come in a wide range of shapes and sizes. Their appearance is an evolutionary response to the plant’s needs, in particular factors such as the habitat in which it grows, the degree of shading or exposure dictated by its favoured growing location, and rainfall. In most instances, all the leaves on a given plant are likely to be broadly similar to one another, although size tends to decrease up the stem of a plant. However, to complicate matters, basal leaves can be entirely different in appearance from stem leaves. This applies to a number of species, notably some umbellifers.

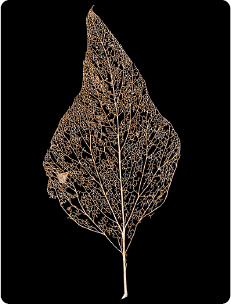

In essence, leaves are thin and rather delicate structures. However, rigidity is maintained by a network of veins through which pass the ingredients required for photosynthesis, and the products of the process.

The intricate network of veins in a leaf is often best appreciated after autumn leaf-fall in deciduous species. Softer tissue decomposes before the veins themselves disintegrate, leaving striking leaf skeletons.

Leaf shape is not an infallible guide to plant identity, so its importance as an identifying feature is secondary to the appearance of flowers. There are many instances where entirely unrelated plants have superficially very similar leaves and great care must be taken when using leaf shape alone for identification. However, there are also plenty of instances where leaf shape is distinctive and diagnostic, or where it allows the separation of closely related plants that have superficially similar flowers. So it is worth paying attention to the variety of leaf shapes found among British wild flowers, some of which are shown right and overleaf along with the common descriptive name by which their shapes are known. Also shown are a variety of distinctive marginal features.

OVATE

LANCEOLATE

ROUNDED

POINTED-TIPPED

SPOON-SHAPED

LINEAR

ROUNDED-TIPPED

TOOTHED (DENTATE) MARGIN

HEART-SHAPED (CORDATE) BASE

PINNATE

PALMATE

LOBED MARGIN

CLASPING BASE

TRIFOLIATE (OR TREFOIL)

FINELY DIVIDED

HABITATS

WHEREVER CONDITIONS ARE SUITABLE for life then plants are likely to grow. Although some species are rather catholic with regard to where they grow, most are much more specific, influenced by factors such as underlying soil type, whether the soil is waterlogged or free-draining, summer and winter temperature extremes and so on. Consequently, where environmental conditions are broadly similar, the same plant species are likely to be found; where these communities are recognisably distinct they are referred to by specific habitat names. In Britain, many of our most distinct habitats owe their existence to past and present human activity, so they are classed as semi-natural in ecological terms.

DECIDUOUS WOODLAND

Woodlands of deciduous trees are found throughout most of the region. They are (or would be, if allowed to flourish) the dominant natural forest type of all regions except in parts of Scotland where evergreen conifers predominate. As their name suggests, deciduous trees have shed their leaves by winter and grow a new set the following spring. The seasonality seen in deciduous woodland is among the most marked and easily observed of any habitat in the region.

Almost all woodland in the region has been, and still is, influenced in some way by man. This might take the form of simple disturbance by walkers, at one end of the spectrum, or clear-felling at the other. Man’s influence is not always to the detriment of wildlife, however. Sympathetic coppicing of Hazel and Ash, for example, can encourage a profusion of wild flowers. In particularly rich locations, carpets of Bluebells, Wood Anemones and Wood Sorrel form the backdrop for more unusual species such as Early Purple Orchid and Greater Butterfly Orchid, Goldilocks Buttercup and Herb-Paris.

Centuries of woodland coppicing have inadvertently created the perfect environment for Bluebells to thrive. A carpet of these lovely plants is a quintessentially English scene.

CONIFEROUS WOODLAND

Areas of native conifer woodland are restricted to a few relict pockets of Caledonian pine forest in the Highlands of Scotland. Conifers that are seen almost everywhere else in Britain and Ireland have either been planted or have seeded themselves from mature plantations. Our native conifer forests harbour an intriguing selection of plants, such as various wintergreen species, Twinflower and Creeping Lady’s-tresses, but conifer plantations are usually species-poor.

HEDGEROWS AND SCRUB

Once so much a feature of the British countryside, hedgerows have suffered a dramatic decline in recent decades. Many hedgerows have either been grubbed out by farmers keen to expand arable field sizes or, more insidiously, wrecked – both in terms of appearance and in their value to wildlife – by inappropriate cutting regimes.

The extent of scrub in the landscape has also diminished in recent times. Although scrub is difficult to define in strict habitat terms, most people would understand the word to mean a loose assemblage of tangled, medium-sized shrubs and bushes interspersed with patches of spreading plants such as Bramble and areas of grassland. Scrub is frequently despised by landowners – sometimes even by naturalists too – but its value to many species formerly considered so common and widespread as not to merit conservation attention should not be underestimated.

Hedgerows usually comprise the species, and acquire the character, of any woodland edge in the vicinity. Scrub, too, reflects the botanical composition of the surrounding area. However, because scrub is essentially a colonising habitat, and not an established one, the bushes and shrubs that comprise tend to be those that grow the fastest.

GRASSLAND AND FARMLAND

Full of wild flowers and native grass species, a good grassy meadow is a delight to anyone with an eye for colour and an interest in natural history. Unfortunately, prime sites are comparatively few and far between these days, either lost to the plough or ‘improved’ by farmers for grazing, by seeding with fast-growing, non-native grass species and by applying selective herbicides. When this happens, the grassland loses its intrinsic botanical interest and value.

It should not be forgotten that, in Britain and Ireland, grassland is a man-made habitat, the result of woodland clearance for grazing in centuries past. If a site is to be maintained as grassland, continued grazing or cutting is needed to ensure that scrub does not regenerate. In the past, the way in which grassland was managed had the beneficial side-effect – from a naturalists’ perspective – of increasing botanical diversity. Under modern ‘efficient’ farming regimes the reverse is the case.

Although arable fields may fall loosely into the category of grasslands (crop species such as wheat, barley and oats are grasses after all), their botanical interest tends to be minimal in many areas. Modern herbicides ensure that ‘weeds’ are kept to a minimum, and decades of chemical use have resulted in the soil’s seed bank being depleted dramatically. Many of the more delicate arable ‘weed’ species are essentially things of the past, often relegated to a few scraps of marginal land that escape spraying either by luck or, in a few instances, through the foresight of farmers. Arable weeds depend on disturbance, being unable to compete in stable grassland communities. So there is a sad irony to the fact that grant-funded ‘conservation’ schemes that create wildlife ‘headlands’ are often the final nail in the coffin for these scarce species, which become crowded out by the vigorous growth of seeded rank grasses and clovers.

HEATHLAND

Heathlands are essentially restricted to southern England, with the majority of sites concentrated in Surrey, Hampshire and Dorset. However, further isolated examples of heath-land can be found further afield, in south Devon and Suffolk, for example, and in coastal districts of Cornwall and Pembrokeshire. This fragmented distribution adds to the problems that beset the habitat: ‘island’ populations of plants and animals have little chance of receiving genetic input from other sites.

Heathland owes its existence to man, and came about following forest clearance on acid, sandy soils. Regimes of grazing, cutting and periodic burning in the past have helped maintain heathland, and continued management is needed to ensure an appropriate balance between scrub encroachment and the maintenance of an open habitat. Ironically, man is also the biggest threat to the habitat: uncontrolled burns cause damage that takes decades or more to repair, while the destruction of heathland for housing developments obviously means the loss of this unique habitat for good.