Полная версия

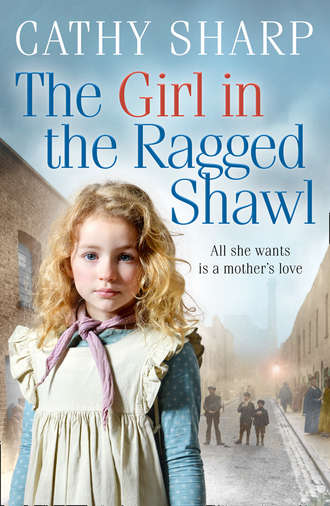

The Girl in the Ragged Shawl

She found Ruth in the kitchen helping Cook prepare vegetables and told her what the mistress had instructed her to do. Ruth nodded, for she was used to being given such tasks. Mistress Simpkins always passed on the children she could not be bothered with herself, and it was usually Ruth that had the task of caring for them.

‘Let’s fetch the lad here,’ she told Eliza with a smile. ‘We’ll give him a drop of the master’s stew – is that all right with you, Cook?’

‘Aye, Ruth lass. Let the boy get some food inside him and he’ll feel more like talkin’.’ Cook smiled at them. ‘I daresay you wouldn’t mind a drop of my soup, Eliza love? No need for the mistress to know. She grudges every penny she spends on our food, but she dare not question what I spend on the master’s dinners.’ She winked at them. ‘A little deception does no harm now and then. What say you, Eliza?’

‘I don’t want you to get into trouble or Ruth …’

‘Nay, lass, there’ll be no trouble. Mistress knows if I left she could not replace me. There’s not many would work here for the pittance they pay. So she would have to do the cooking herself or get another inmate to do it and none of them have the first idea how to start so I’m safe enough.’

Eliza smiled and took the bowl of soup Cook offered, drinking it down quickly as if she feared Mistress Simpkins might appear and snatch it from her.

‘Lawks a’ mercy,’ Cook said. ‘You’ll get hiccups, girl. Off with the pair of yer and let me get on or there’ll be no soup for the men.’

Ruth winked at Eliza as they left the kitchen. ‘She’s not a bad woman, Eliza for all her sharp tongue at times.’

‘I like Cook,’ Eliza said and smiled, the goodness of the soup giving her a lovely warmth inside. ‘Sadie said the new boy was a gypsy – his family travel, like yours, Ruth.’

‘My father was a tinker. He mended pots and pans and did odd jobs of any sort, but he wasn’t Romany,’ Ruth told her. ‘The true Romany is special, Eliza. The women often have healin’ powers – and the men are handsome and strong, and some of them could charm the birds from the trees.’

‘Perhaps Joe is Romany,’ Eliza said. She pointed across the wide, cobbled courtyard, swept clean every morning by the older boys no matter the weather. It was bounded by high walls with only one way out: a pair of strong iron gates that were impossible to scale. ‘Look, that must be him, standing near the gates.’

‘Aye, the poor lad be feelin’ shut in,’ Ruth said and there was pity in her tone. ‘I mind my father standin’ like that for many a month afore he grew accustomed to this terrible place.’

‘Doesn’t he know that he can’t leave unless his father comes for him – or unless he’s taken by a master?’

‘If he knows, he won’t admit it in his heart,’ Ruth said. ‘A lad like that needs to be free to run in the fields and breathe fresh country air.’

‘I’ll go to him.’ Eliza set off at a run, ignoring Ruth’s murmured warning to take care. As she approached, the boy turned and looked at her, glaring and angry, his blue eyes smouldering with suppressed rage. ‘Are you Joe?’ Eliza asked. ‘I’m Eliza. I was brought here when I was a babe. It is a terrible place but I’m goin’ to leave one day and then I’ll go far away, somewhere there are fields and wild flowers in the hedges.’

‘You don’t know where to find them,’ the boy said, and Eliza was startled by the sound of his voice that had a lilting quality. ‘You’re not Romany.’

‘No – are you?’ He inclined his head, his eyes focused on her so intently that Eliza’s heart jumped. ‘I think I should like to live as you did – travellin’ from place to place.’

‘In the winter it be hard,’ he said. ‘Ma took sick again this winter and Pa came to Lun’un lookin’ for a warm place to stay for her and work – but they said he was a dirty gypsy and a thief and they put him in prison for startin’ a fight, which he never did.’ His eyes glittered like ice in the sun. ‘My Pa never stole in his life nor did harm to any. He be an honest man and good – I hate them and all their kind.’

‘So do I,’ Eliza said and moved a little closer. ‘Master is not too bad as long as you don’t disobey him openly – but mistress is spiteful and cruel and she’s boss of her brother. I hate her so much. I should like to kill her.’ Eliza made a stabbing movement with her hand. ‘See, she’s fallen down dead.’

A slow smile spread across the newcomer’s face. ‘I like you, Eliza,’ he said. ‘Shall we kill her together?’

‘Yes, Joe – one day, when we’re bigger and stronger,’ Eliza said. ‘For now we have to do as she says – or pretend to. Let her think she rules, but she can’t rule our hearts and minds – she can’t break us even if she beats us. If you come with Ruth and me, Cook will give you some of the master’s stew. It’s good, much better than they give us. Mistress said we shouldn’t feed you until you were bathed and changed your clothes, but Cook said you should eat first. Will you come?’

‘I’ll come for you,’ Joe said. ‘You’re pretty – like my ma. She’s beautiful, but the travellin’ don’t suit her and she be ill in the winter.’

‘Where is your ma?’ Eliza offered her hand and he took it, his grip strong and possessive. Her eyes opened wide and she seemed to feel something pass between them, a bond that was not spoken or acknowledged but felt by both.

‘Bathsheba took her to Ireland,’ Joe told her. ‘She’s Pa’s sister and travels with us, though she has her own caravan. They wanted me to go with them but I ran away to be near my pa. When I can I shall visit him in prison and let him know I be waitin’ for him.’

‘You will need to get away from here,’ Eliza said. ‘How did they catch you?’

‘I went to the prison gates and demanded to see my pa; they tried to send me away but I refused and kept shouting at them. They sent the constable to arrest me and he brought me here because I had no money and nowhere to stay and he said I be a vagrant.’

‘They won’t let you go unless your pa comes for you or a master takes you,’ Eliza said with the wisdom of a child reared in the workhouse. ‘You could try to escape. Not many do because it’s hard out there, so they tell us. I’ve never been anywhere …’ Eliza’s eyes filled with tears, for there were times when she ached to be free of this place. Joe reached out to her, smoothing her tears away with his fingers.

‘You shouldn’t cry. You should just hate them. You’re be too pretty to cry, Eliza. Your hair’s like spun silk … My ma has hair like yours but ’tis darker, not as silver as yours.’ He smiled at her and leaned his head closer. ‘When I escape I’ll take you with me.’

‘Oh yes, please let me come with you,’ Eliza begged. ‘We could go and live in the fields and you can show me where the wild flowers grow.’

Joe nodded and then scowled. ‘I be hungry. ’Tis ages since I’ve eaten more than a crust of bread. I’ll wash ’cos I don’t like nits in my hair – but I want my own clothes. Can you wash them for me and give them back? If she gets them I’ll have to ask her for them before I leave and she wouldn’t let me go for I am too young to be alone on the streets – at least that’s what they claim.’

‘Yes, I can do that for you,’ Eliza said, though if she was caught stealing from the laundry she would be beaten. ‘You’ll have to wear what you’re given for now, but you can hide your things and then when you escape, you can wear them.’

‘You’re a bright girl,’ Joe said and smiled. ‘Can you read and write, Eliza?’

‘Rector taught us to write our names once and Ruth helped me practice, but I can’t read,’ Eliza admitted and the smile left her eyes. ‘Mistress never lets me take lessons with the vicar now. She says all I need to know is how to address my betters.’

‘You’re better than her,’ Joe said fiercely and once again his eyes glittered like ice, ‘and don’t you forget it. Ma taught me to read, write and my numbers – and I’ll teach you.’

‘Yes.’ Eliza felt the warmth spread through her. ‘We’ll be friends, Joe – me and you. Whatever they do, we’ll always be friends …’

CHAPTER 4

‘It is time the rules were reformed,’ Arthur said to a group of men as they moved to leave the inn parlour that had been their meeting place. ‘Some of them are too harsh – and I believe the wardens should be more strictly regulated.’

‘You would relax the rules for the undeserving and regulate the hard-working men and women who enforce them?’ one of the board members asked incredulously. ‘Have you lost your wits, Stoneham?’

‘No, Sir Henry, I think not,’ Arthur replied. ‘I believe that the rules were set up in good faith but they are open to abuse by the master and the mistress – and I think it is time they were reviewed. Just as I do not believe that a master should be allowed to beat his servant for some small misdemeanour.’

‘Good grief! You would turn society on its head,’ Sir Henry said, staring at him with eyes that bulged in disbelief. ‘You cannot imagine what chaos could ensue, my dear Stoneham. Your compassion does you credit – but they are cunning wretches. You must not believe a word they say. A servant who complains of his master’s whip has probably stolen from him – and if dealt with firmly would be sent for a year’s hard labour. He is lucky to escape with a beating.’

‘Come, sir,’ Toby said and raised a lazy eyebrow. ‘Are all the poor undeserving wretches?’

‘Most – and if not they are usually insolent and impertinent and should be kept in their place or a man will not be able to keep hold of his property. Only those that prove their worth and know their place should be promoted.’

‘And what if I had proof that the rules were being abused and vulnerable girls harmed?’ Arthur asked.

‘Well, in certain circumstances we might have to replace the master and the woman who assists him as matron or whatever.’ Sir Henry yawned, obviously bored. ‘These meetings are tiresome. I must be off to my club – good-day, gentlemen.’ He tipped his hat and went on his way muttering about reformers.

‘You see what I am up against,’ Arthur said, and his gaze followed the baronet in disgust. ‘Any mention of reform and they fear for their property.’

‘Sir Henry does not speak for us all,’ a deep voice said from behind them and they turned to see another of the governors looking at them with interest. ‘I agree that the rules may need updating.’

‘Major Cartwright …’ Arthur nodded. He was not inclined to make an ally of the old soldier and yet it seemed that he might have to take what votes he could get. ‘I believe that some of the punishments used on children are too severe.’

‘Ah yes, the poor young ones,’ the major said but looked odd. ‘Well, I am not against reform. You may rely on me if you need my vote – good day, gentlemen.’

Arthur watched him leave. ‘Why don’t I trust that man?’

‘I’ve met his sort before …’ Toby shook his head. ‘Not sure you are right not to trust him, but he might be an ally if you need one, Arthur.’

‘I’m glad you decided to sit in this morning,’ Arthur said. ‘Now, I propose to treat you to a dinner at my club to make up for all the boring chatter you’ve been forced to endure.’

‘And so I should think,’ Toby said and twirled his Malacca cane with its silver knob. ‘At least you got the money for the new drains passed so it’s not all bad, my friend.’

‘Tell me, Molly, is that my brat in there?’ Master Simpkins smiled and touched her swollen belly. ‘I dare swear I’ve swived you enough to claim it.’

Molly laughed and reached for the tankard of strong ale on the table beside her, drinking deeply from it and wiping her chin with the back of her hand before kissing him on the mouth and thrusting her tongue inside. He tasted of strong ale and his breath smelled, but she’d known worse and she tolerated him. Robbie could be coarse, and he’d taken her virginity by force when she was a young girl, but she’d more or less forgiven him because she accepted that it was her lot in life. Robbie wasn’t the worst of the men she served and these days she used him as much as he used her. He was weak, a creature of lust and greed, and yet he could be generous if he chose. Because of Robbie, Molly was able to come here to have her child and leave again when she chose.

Few knew that he was part owner of the whorehouse where she worked and lived, though he had nothing to do with its daily life, but Molly had discovered it long since. It made her smile to think that his sister was ignorant of what her brother got up to in his quarters.

Oh, Mistress Simpkins had her own dirty little schemes but Molly would bet that Robbie was as ignorant of what his sister was up to as she was of his part-ownership of the brothel. However, whereas Molly could accept Robbie’s involvement, she hated his sister and what she did with a deep vengeance. Grown women selling themselves for money and a life of comparative ease was one thing, but condemning children to the brutality of the evil men that used them was quite another. If she’d thought that she could stop Joan Simpkins from selling the children she would have told Robbie, but she knew he would either disbelieve her or be unable to control his sister; Joan was the stronger of the two and though she held her post through him, he seldom interfered with her.

‘You’re not a bad old sod,’ she told him now. ‘I can’t let yer ride me, Robbie love, ‘cos I’m too big – but I’ll give yer a treat if yer like.’ She moved her hand suggestively to his bulging breeches and smiled. ‘You’m be hung like a horse, me darling. It must be painful fer yer with yer breeches so tight … let Molly ease yer.’

‘Yer the best, Molly. Yer always look after me,’ he said and pulled her in for a kiss. ‘Get on with it then – and take your time.’

Joan Simpkins paused outside her brother’s door listening to the disgusting sounds coming from inside. He and his whores thought she was ignorant of what they did in his rooms, but she’d learned what he was long ago – even before his wife died. To hear him speak of his wife anyone would think he’d adored the woman he called a saint, but if he had loved her it had never stopped him indulging his baser needs with whores.

She frowned and turned away, making her own secret tour of all the wards while her brother was otherwise engaged. He had no idea that she overlooked his side of the workhouse, but she knew all the spyholes and enjoyed watching men, women and children as they moved about their quarters or lay in their beds, believing that no one but their companions knew of what they did in the hours of darkness; their misery satisfied her and eased her own self-pity.

Joan had learned of the baseness of these creatures when she was but a young girl. Spying on them, she saw the furtive couplings between certain types of men, and it pleased her that she knew their secrets – the filthy beasts were no better than animals to her mind. She grudged what comfort their couplings gave them for she thrived on the suffering of others. When gentlemen instructed that these creatures should be treated as human beings she hardly knew how to contain her ire. Men like Mr Stoneham, used to the luxury of clean linen, warm fires, and all the wine and choice foods he desired, had no idea what kind of beasts they dealt with here; ignorant, filthy, base creatures who would do nothing to help themselves unless prodded to it. They rutted like animals and deserved no better treatment.

Joan also knew that some of the men fought off those others and sought their pleasures with the women, sometimes their wives if they could find a way, but often another young woman taken with her consent and, at times, without. The strict rules meant that the men and women were segregated and locked in their own wings to prevent this kind of thing, but they were cunning and some had discovered how to move about the workhouse even after the doors were locked at night. When she discovered where their illicit key was hidden she would take great pleasure in punishing the culprits. For the moment it amused her that they believed themselves safe.

Joan had not interfered even when she witnessed the rape of a young girl by her own brother. It had amused her to watch for the girl was nothing but an impertinent upstart – and pretty. She deserved her fate.

Soon afterwards, the girl had come to her and confessed she was with child. Joan had told her she had her just deserts for fornicating and offered her a choice – she might go to an asylum for correction or enter a whorehouse. The girl had chosen the life of a whore, which just showed that Joan was perfectly justified in her opinion of her character.

Molly was a slut and always had been. She was a whore at heart and there was no more to be said, but it irked Joan that she seemed to enjoy her life. Why should she be happy and free to come and go when Joan was tied to her post, not by duty but the need for money? When she left this place it would be for good and she needed a great deal of money to live in comfort – or she would one day find herself once more in a place like this but as an inmate.

Eliza lay snuggled up to Ruth beneath the blanket they shared. Now that she was thirteen she was allowed to sleep on the women’s wing instead of being sent to join the other young children at night. Lying close to her friend was the only way to keep warm and Eliza liked being with the woman she called friend, but this night she found it hard to sleep. Joe had told her about his life while he ate his meal in the kitchen and Eliza felt an aching need inside her to see what it was like to be free, to travel wherever she wished.

The only place she’d ever been taken to was the church at the end of Farthing Lane. It was a treat on Sunday and she was given a clean dress on the days she was allowed to go, but that was not often. A group of children and women and a few men went every week, because the Board of Governors insisted that the inmates hear the word of God, but Mistress Simpkins did not allow everyone from her ward to go. A few women and girls were chosen and supervised by Mistress Simpkins and Sadie, and they were dressed cleanly with aprons and little white caps over a grey dress. Eliza sometimes wondered why the men and women did not just walk away on these outings, for neither Sadie nor the mistress could have stopped them, but when she asked Ruth, she’d told her that they simply had nowhere to go.

‘Life is hard in here,’ she’d said looking sad, ‘but it can be terrible cruel on the streets, Eliza. Here we be given food every day; it may not be much and ’tis often hard to stomach, but it is better than no food at all. The men bring their families in when they be close to starvin’. I tried to live on the streets and it’s no place for children, my lovely. There are dangers out there that we be protected from in here. The women won’t leave without their kids and the men won’t leave their families here alone so they stay until work is offered and they can sign themselves out, though many are back in a few months when the work dries up. ’Sides, if they walked off in the uniform they could be taken up fer stealin’.’

Ruth was fast asleep and snoring gently, and Eliza wished she might sleep, but her rebellious nature kept her wakeful. One of these days she was going to run away. She would like it to be with her new friend Joe, but if not she would go alone. Eliza knew her chances of surviving on the streets alone at her age were slight; she had to hold on, to endure the mistress’s spite for another year or so. When she was older she could ask for work and might be given it. At the moment she was too young and slight. Most people wanted a strong girl to do all their chores and Eliza might not look strong, even though the years of hardship had toughened her. They would want an older girl or a woman and that was why she was still here after so many years.

Yet perhaps if she and Joe ran away together they could manage. In the country, perhaps, folk were kinder than in town …

‘I’ve been lookin’ round,’ Joe told Eliza the next morning when they met after breakfast. It was a time when the two sides mixed in the dining room and then dispersed, each to their own work. ‘I’ve been put to work with the men making hemp rope. There’s a man called Bill and he knows a way to get out, though he says he’s not ready to leave yet. I asked him to tell me, but he said if I used it, it would spoil his chances when he goes, but if there is one way there must be others.’

‘No talking!’ Eliza looked up and saw the mistress watching them. ‘Get to your work, girl, or you will feel my stick.’

‘Don’t you dare hurt her,’ Joe said and moved in front of Eliza. ‘Lay a finger on her and I’ll see you dead – I’ll lay a curse on you and you’ll die in agony, withered and alone!’

For a moment the colour left Mistress Simpkins’ face and Eliza thought she saw fear in her eyes, but then in a moment it had gone.

‘I do not believe in your curses, gypsy,’ she said and raised her stick bringing it down hard, but Joe was too quick for her and seized it, twisting it from her hand with a flick of his wrist. ‘How dare you? I shall see you are flogged for this – and you’ll have no food this day.’

Joe stared at her defiantly and then broke the stick over his knee and flung down the pieces. She raised her hand and struck him again about the face but though he flinched he stood firm, his eyes daring her to touch him again.

‘Now then, now then,’ the master’s voice made Eliza spin round for she had not noticed his approach, but Joe and the mistress had not taken their eyes from each other as if neither would give in. ‘What has this boy done to upset you, sister?’

‘He is a disobedient, dirty gypsy and he needs to be punished. He broke my stick and he dared to threaten he would put a curse on me.’

The master looked at Joe severely. ‘Did you do as the mistress claims, boy?’

‘Yes, sir, ’tis true. She be goin’ to hit Eliza and I told her I’d curse her if she did – so she tried to hit me with her stick and I broke it.’

‘Did you indeed?’ For a moment it looked as if the master approved of Joe’s action but then he frowned. ‘Well then, well then, boy – what am I to do with you? This won’t do, you know. I cannot allow you to defy the mistress – even though you are in my ward, not hers.’ His thick brows met as he looked at his sister as if sending her a challenge.

‘He must be flogged and sent to the hole – and no food today, none!’ Mistress Simpkins’ voice had reached a shrill pitch that made the master frown.

He reached out and took hold of the collar of the worn and much-patched jacket Joe was wearing. ‘You come along with me boy,’ he said looking angry. ‘You have upset the mistress and you must be punished.’

Eliza watched as Joe was dragged off, holding back her tears. She was so angry and yet so frightened for Joe. He’d been rebellious from the start because he was used to living free and he didn’t understand how hard life was in the workhouse. Open defiance made the mistress lose her temper and she had been known to beat a child until the blood ran in one of her rages.

‘What are you staring at, girl?’ the mistress snapped suddenly making Eliza jump. ‘Get to your work or you’ll find my stick about your shoulders.’ A glint of temper showed in her eyes as she looked down at the stick Joe had broken. ‘Don’t think that will save you. I’ve another stronger and thicker that that gypsy brat won’t break.’

Eliza turned and walked towards the laundry. Her heart was racing wildly and she wanted to run but she made herself walk. She must never show fear, never show weakness. If the mistress once thought she could break you, she would never let up.

Eliza’s back felt as if it were breaking when she finished her day’s work. She’d filled the vats with hot water from the copper and then stirred ten piles of dirty clothes into the water that had turned a muddy brown colour by the time she’d finished the last. They were only allowed to heat one tub of water a day but they used two tubs of cold water to rinse the clothes, so that when they were mangled for the last time they smelled reasonably fresh and the dirt had gone. Once the washing was hanging high above their heads under the vaulted ceiling, they had to empty all the vats and tip the filthy water into the ditches that ran past the rear of the laundry out into the gutters in the lane and finally into the sewers. It was back-breaking work and all the women were exhausted by the time they were told to take their places for the second meal of the day in the dining-hall.