Полная версия

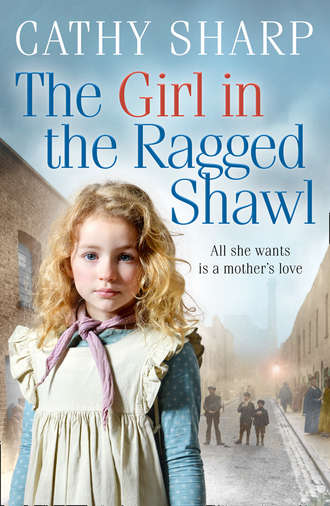

The Girl in the Ragged Shawl

‘If ever you dare to tell Mr Stoneham or the doctor that I shut you in the cellar I shall kill you!’ she hissed

Eliza opened her eyes and stared at her. The mistress met her look for a moment and then walked away. Eliza believed her threat, because children often died of fever or near starvation in this fearful place and one more would not be noticed. The mistress stood in place of a matron, which every workhouse was meant to have, but she cared little for the health of her inmates and anyone who was sick was left to rot in the infirmary unless Ruth or one of the other women cared for them.

‘Eliza, are you awake at last?’ Ruth’s face was bending over. ‘Can you drink a little milk now, my lovely?’

‘Yes please.’ Eliza felt herself raised against the hard pillows and a cup was held to her mouth. ‘She will punish us, Ruth. Just as soon as she thinks it safe, she will punish us again.’

CHAPTER 2

‘I swear there is something badly wrong at the workhouse in Whitechapel,’ Arthur Stoneham said to his companion as they lingered over the good dinner of roast beef and several removes Arthur’s housekeeper had served them. ‘I saw a child there today and she was barely alive. The tale was that she’d fallen down the stairs of the cellar when hiding to avoid doing her work – but those bruises looked to me very like she’d been beaten, and the idea of her having locked herself in the cellar is ludicrous.’

‘What do you mean to do about it?’ Toby Rattan asked. The younger son of Lord Rosenburg, Toby tended to spend his days in idle pursuits, gambling on the horses and cards, riding and indulging his love of good wine and beautiful women. He yawned behind his hand, for at times Arthur could be a dull dog, unlike the bold adventurer he’d been when the pair was first on the town in 1867 when they were both nineteen years of age. Something had happened about that time and it had sobered Arthur, making him more serious, though Toby had never known what had taken that devil-may-care look from his friend’s eyes, but their friendship had held for more years than he could recall since then, despite the change in Arthur’s manner.

‘I am trying to change things, but it is very slow, for although some of the board are well-meaning men they believe the poor to be undeserving,’ Arthur said and laughed as he saw Toby’s expression. ‘You did not dine with me this evening to hear about such dull stuff as this, I’ll wager.’

‘If only you would wager,’ Toby said and smiled oddly, because he was inordinately fond of his friend, even though he did consider him slow company when he got on his high horse about the state of the poor. ‘Actually, I agree with you, my dear fellow. If it would not bore me to death I would sit on the Board of Governors with you and help you get rid of that wretched woman.’

‘Ah, dear Toby, as if I would ask you to sacrifice so much,’ Arthur said and arched his left eyebrow mockingly. Toby was as fair as Arthur was dark and the two men were of a similar build and well-matched in form and looks, turning heads whenever they entered a room together. Toby grinned, for his sense of humour matched Arthur’s. ‘Fear not, all I would ask of you is that you donate a small portion of your obscene fortune to helping me repair and reform the workhouse.’

‘In what way?’ Toby smiled affectionately, because he admired his friend’s unswerving purpose in trying to rescue unfortunates from poverty and worse. ‘Are you going to install gas lighting or new drains?’

‘Firstly, they need a new roof, and I have already installed some new water pipes, but there was an outbreak of cholera in that area recently and I fear more needs to be done in the area as a whole,’ Arthur said and laughed as Toby’s lazy attitude fell away and he sat forward, suddenly intent. ‘Gas lighting is going a little too far for the moment, but I was hoping for both money and your help with changing opinions. For most the workhouse is a place of correction—’

‘Was that not its true purpose?’ Toby interrupted.

‘In 1834, because the demands of the destitute were so heavy on some parishes, the law was changed so that the poor could not claim on the parish unless they entered the workhouse,’ Arthur informed him, though he doubted his friend was ignorant of the law. ‘However, it was meant as a place of refuge where men, women and children would be cared for in return for work. The rules are strict, because they have to be – but I think Mistress Simpkins is not the only one who abuses them.’

‘In what way?’

‘I am fairly certain that they interpret the laws, using them for their own benefit. That girl had been in the cellar for three days, when the legal punishment in solitary confinement is one day, and she was lucky to be alive. Only a week or so back a boy died in mysterious circumstances in that same house and I believe the conditions to be much the same in many other workhouses.’

‘You do not hold to the opinion that the poor are shiftless and undeserving?’ Toby murmured one eyebrow lifting. ‘Most would say they have to prove their worth.’

‘Money is a privilege, not a right,’ Arthur said. ‘If I had a lazy servant to whom I paid good wages I would dismiss him – but I spoke to some of the men in that place and I believe that they are ready to work and care for their families. When they do have a situation, the wages are so poor that they can save nothing for the times when there is no work and so are forced into the workhouse through no fault of their own.’

‘You are a reformer, my friend,’ Toby chided. ‘You should take my father’s seat in the House of Lords.’

‘I leave the law-making to men like your father, Toby, but I would ask you to beg him to add his voice to those who seek reform. It is time the poor were treated with respect and given help in a way that does not rob them of their pride. Men should not be forced to take their families into the workhouse – and women should not be forced to prostitution to keep from starving. I also have it in mind to set up a place of refuge for such women.’

‘You know I am in agreement with that.’

‘Yes, I know – but I need help with these reforms at the workhouse.’

‘You have my promise,’ Toby said. ‘And if you need money for your reforms I will offer you five thousand immediately.’

‘I was sure I could count on you,’ Arthur murmured. ‘What I need most is your support. The more voices raised against those dens of iniquity the better, Toby, and I speak now of the whorehouses, not the spike, as the unfortunates within its walls call the workhouse. I would wish to have all brothels closed down, but every time I try to raise the subject I am told that such women are more at risk on the streets. At least in the brothels they are protected from violence and their health is monitored, so they tell me – and I fear it may be true, poor wretches.’

‘It is the children certain men abduct and initiate into their disgusting ways that disturbs me,’ Toby said, all pretence of being a fop gone now that Arthur had raised a subject that angered him. Toby enjoyed a dalliance with a beautiful woman as much as the next man, but he chose married or widowed women from his own class, women who were bored with their lives and enjoyed the company of a younger man. Visiting whores at houses of ill repute was something he had not done since he’d seen for himself the terrible consequences such places inflicted on the women forced to serve them. ‘If a woman chooses to support herself in this way it is her prerogative, but to force mere children! I told you of my groom’s twelve-year-old daughter who was snatched from her own lane, not two yards from her home?’

‘Yes, you did. When she was eventually found two years later, she had syphilis and was deranged. I know how that angered you, Toby.’ It was sadly but one case of many. Victorian society was outwardly God-fearing and often pious to the extreme, but it hid a cesspool of depravity and injustice that no decent man could tolerate.

‘Had I found the person that snatched poor Mary, I should have killed him,’ Toby vowed.

‘Exactly so.’ Arthur smiled at him. ‘I knew you were of the same mind, my dear friend. In our society the whore is thought of as the lowest of the low, but who brought her to that state? Men – and a State that cares nothing that a woman may be starving and forced to sell herself to feed her children.’

‘Yes, true enough, we are all culpable, but the ladies of the night do have a choice in many cases – the children sold into these places do not, Arthur. It is the children we must protect.’

Arthur reached forward to fill his wine glass. ‘We are in agreement. Thank you, Toby. I shall put your name at the top of my list – and I know of one or two influential ladies who will add theirs, but it is men we need, because for the most part they have the money and the power.’

‘I shall ask my father and brother to add their names. They will not do more, though of course I can usually extract a few thousand from my father for a good cause.’ Toby smiled, because he knew that his father indulged him. ‘I find the ladies are more vociferous when it comes to demanding change.’

Arthur raised his glass. ‘To your good health, Toby. Now tell me, have you visited the theatre of late?’

Arthur looked at himself in the dressing mirror as he prepared for bed. It was three in the morning and Toby had just departed to visit a certain widow of whom he was fond, and she of him. Their arrangement had lasted more than a year and Arthur thought it might endure for some time because the pair were suited in many ways, and Toby was too restless to marry.

He envied his friend in having found a lady so much to his liking. Arthur had thought of marriage once or twice but at the last he had drawn back, perhaps because he was still haunted by that time … No, damn it! He would not let himself remember that which shamed him even now. It was gone, finished, and he had become a better man, and yet he had not married because of his secret. He could never wed a young and beautiful girl, for he would soil her with his touch, and as yet he had not found a woman of more mature years of whom he might grow fond. Perhaps it was his punishment that he could not find love in his heart.

He had good friends, several of whom were married ladies that he might have taken to bed had he so wished, but he lived, for the most part, a celibate life. Yet he enjoyed many things – sharing a lavish dinner with his friends was a favourite pastime, as was visiting Drury Lane and the other theatres that abounded in London. On occasion he had even visited a hall of music, where singers and comedians entertained while drinks were served. He found it amusing and it helped him to see much of the underlife that ran so deep in Victorian society. It was seeing the plight of women thrown out of the whorehouse to starve because they were no longer attractive enough to serve the customers that made him feel he must do something to help, at least a few of them.

Mixing with a rougher element at the halls of music brought him in touch with the extreme poverty that the industrialisation of a mainly rural nation had brought to England. It had begun a century before, becoming worse as men who had been tied to the land followed the railways looking for work and then flocked to the larger towns, bringing their women and children with them. The lack of decent housing and living space had become more apparent and the poor laws which had once provided help, with at least a modicum of dignity, had failed miserably to support a burgeoning population. Public houses catered to the need to fill empty lives with gin, which brought temporary ease to those suffering from cold and hunger. It was because the towns and cities had become too crowded that the old laws were no longer sufficient to house and feed those unable to support themselves, so the workhouses had been built. All manner of folk, weak in mind and body were sent there, as well as those who simply could not feed themselves.

Arthur frowned as he climbed into bed and turned down the wick of his oil lamp. He’d long ago had gas lighting installed downstairs but preferred the lamps for his bedroom. His thoughts were still on the workhouse. It had been thought a marvellous idea to take in men, women and children who were living on the streets or in crumbling old ruins in cities and towns; to feed them, clothe them, and give them work, though production of goods made cheaply by the inmates was disapproved of by the regular tradesmen, who felt it harmed their livelihoods. Indeed, it should have been a good solution, but it was being abused. Women like that Simpkins harridan abused their power. Arthur frowned as he closed his eyes. His instincts told him that she had beaten the boy that died and locked that poor girl in the cellar – but was that all she was up to?

CHAPTER 3

Joan Simpkins was in a foul mood. She had sharply reprimanded by her brother, because he’d been warned that if there were more deaths they would be investigated and he could lose his ward-ship of the workhouse.

‘You must curb your temper,’ he’d told Joan after the latest meeting of the Board of governors. ‘I’ve been informed that we’re bein’ watched and if they find we’re mistreating the inmates we’ll be asked to leave.’

Joan felt her temper rise. Nothing annoyed her so much as knowing that those mealy-mouthed men and women, who understood little of what the poor were actually like, taking her to task. The Board consisted of gentlemen, prosperous businessmen, wives of important men, and even a military officer – and what did they know of the stinking, coarse wretches she was forced to deal with every day? Even when water and soap was provided some of them didn’t bother to wash, and some thought it dangerous to take off the shirt they’d worn all winter until it was mid-summer – and the women who came to the workhouse bearing an illegitimate child got no sympathy from Joan; they were whores and wanton and deserved to be treated as such. She made them wear a special uniform that proclaimed their sin and, if she had room, segregated them from the others in a special ward and made them scrub floors until they dropped the brat.

Now, she glared at her brother. ‘That wretched girl accused me of causing that stupid boy’s death. I had to make an example of her. If I hadn’t nipped it in the bud there would’ve been a rebellion. If something like that reached the ears of that interfering man Arthur Stoneham …’

‘Well, well, I daresay you had your reasons. However, Mr Stoneham has been very generous to us, Joan. He paid for the installation of new water pipes and we’ve not had a return of the cholera since then. He has granted us money towards some very necessary repairs to the roof and that will give the men work for weeks and us extra money.’

It was all right for her brother, Joan thought resentfully. Robbie was weak and lazy. He always took his cut of any money that came in. The funds for running the workhouses were raised by taxing the wealthy, which caused some dissent, but others saw it as a good thing that vagrants were taken off the streets, and made donations voluntarily. Joan did not share in her brother’s perks and was only able to save a few pence on the food and clothing she supplied to the women and children in her ward. If it were not for her other little schemes she would not have a growing hoard of gold coins in her secret place.

Joan hated living in the workhouse. The inmates stank and their hair often crawled with lice when they were admitted. Most of them obeyed the rules to keep themselves clean, but there were always some who were too lazy to bother. It was all very well for Mr Stoneham and the doctor to say the inmates should be given more opportunities to bathe. Heating water cost money and so did the soap she grudgingly gave her wards. She needed to pocket some of the funds she was given for their upkeep, because one day she intended to leave this awful place.

Joan had dreams of living in a nice house with servants to wait on her, and perhaps a little business. Once, she’d hoped she might find a man to marry her, but she was now over thirty and plain. Men never turned their heads when she walked by in the market and she resented pretty women who had everything given to them; like the woman who had brought that rebellious brat in and begged her to keep her safe from harm.

‘One day I’ll come back and pay you in gold and take her with me,’ the woman had promised, her eyes filled with tears.

She’d crossed Joan’s hands with four silver florins and placed the squalling brat in her arms. As soon as she’d gone, Joan had given the brat to one of the inmates and told her to look after it. She’d told Ruth that the child had been brought in by a doctor, though she hardly knew why she lied. Perhaps because she liked secrets and she’d believed then that the woman would return and pay to take the girl with her. She’d kept the girl all these years, refusing two offers to buy her, because of the woman’s promise, but the years had passed and the girl was nearly thirteen. She was a nuisance and caused more trouble than she was worth. It was time to start thinking what best to do with her …

Eliza paused in the act of stirring the large tub of hot water and soda. A load of clothes had been dumped into it earlier and it was Eliza’s job to use the wooden dolly stick she’d been given to help release the dirt from clothes that had been worn too long. They smelled of sweat, urine and excrement where the inmates wiped themselves for lack of anything else, and added to the general stench of the workhouse.

It was steamy and hot in the laundry, though the stone floors could be very cold in winter, especially if your feet were bare, and Eliza had been set to work here again once she recovered from her ordeal in the cellar. So far she’d been asked to stir the very hot water and then help one of the other women to transfer the steaming clothes to a tub of cold water for rinsing. Eliza wasn’t yet strong enough to turn the mangle they used to take out the excess liquid before the washing was hung to dry on lines high above their heads, which were operated by means of a pulley.

‘Watch it, girl,’ a cackling laugh announced the approach of Sadie, the oldest inmate of the workhouse. She’d been here so many years she couldn’t remember any other life. ‘Mistress be in a terrible rage this mornin’.’

Eliza looked at the older woman in apprehension. Sadie was handy with her fists on occasion and Eliza had felt the brunt of her temper more than once. She was the only one that didn’t seem to fear the mistress and was seldom picked on by her.

‘I’ve done nothin’ wrong, Sadie,’ Eliza said. ‘Do you know what has upset her?’

‘I knows the master took in a boy this mornin’ – a gypsy lad he be, dirty and rough-mannered, and mistress be told to have him bathed and feed him. She can’t abide gypsies.’

‘What exactly is a gypsy? I’ve heard the word but do not know what it means.’

‘They be travellin’ folk,’ Molly, another inmate, said coming up to them with an armful of dirty washing. They ain’t always dirty nor yet rough-mannered. I’ve known some, what be kind and can heal the sick.’

Sadie scowled and spat on the floor. ‘You’m be a dirty little whore yerself,’ she snarled and walked off.

‘Sadie’s in her usual cheerful mood.’ Molly winked at Eliza. ‘Do you want a hand with the rinsing, Eliza love?’

‘Would you help me?’ Eliza asked hopefully. ‘Sadie is supposed to give me a hand lifting the clothes into the tub of cold water, but she gets out of it whenever she can.’

‘You’re too small and slight for such work, little Eliza,’ Molly said and grinned at her. ‘And I’m too big.’ She laughed and looked at her belly, because she was close to giving birth again. Molly had been to the workhouse three times to give birth since Eliza had been here and each time she’d departed afterwards, leaving the baby in Mistress Simpkins’ care. Ruth had told her that the warden sold the babies to couples who had no children of their own.

Since workhouse children who were found new lives were thought to be lucky, no one sanctioned the mistress for disposing of the babies as she chose.

‘You might hurt yourself,’ Eliza said as Molly took up the wooden tongs. ‘If you lift something too heavy it might bring on the birth too soon.’

‘What difference?’ Molly shrugged. ‘If the babe be dead it will be one less soul born to misery and pain.’

Eliza looked up at her. ‘Would you not like to keep your child and love it?’

‘They wouldn’t let me. I should have to leave the whorehouse and I have nowhere else to go and no other way of earning my living,’ Molly said and pain flickered in her eyes. ‘They own me, Eliza love, body and soul.’ She smiled as she saw Eliza was puzzled. ‘You don’t understand, and I pray to God that you never will.’

‘If you are unhappy why don’t you go far away?’ Eliza asked. ‘When I’m older I shall go away, go somewhere there are flowers and trees and fields …’

‘What do you know of such things?’ Molly laughed as she started to transfer clothes from the steaming hot tub to the vat of cold water.

‘Ruth’s father was a tinker and they used to travel the roads. He found work where he could and they lived off the land, foraging for food and workin’ for what they could not catch or pick from the hedges.’

‘And where did that get them?’ Molly said wryly. ‘He took ill one winter and was forced to bring them into the workhouse. Ruth Jones has watched all her family die, one by one, and now what does she have to look forward to? It be a life of toil in the workhouse unless she be given work outside – and when men come looking for a servant we all know what they want.’ Eliza shook her head and Molly laughed. ‘No, you be innocent as a new-born lamb, little one, but that won’t last – and when you understand the choice you’ll know why I choose the whorehouse.’

Eliza did not answer. She did not consider that Molly was free, for Ruth had told her the whorehouse was no better than the workhouse, even though the food was more plentiful and at least Molly had decent clothes and was able to wash when she wanted.

‘You, girl – come here!’

Eliza jumped because she’d had not noticed the mistress approaching. She left the rinsing to Molly and went to stand in front of the mistress, but instead of hanging her head as most of the inmates did, she looked her in the face and saw for herself that Sadie was right: mistress was in a foul mood.

‘There’s a boy,’ Mistress Simpkins said, looking at Eliza with obvious dislike. ‘He’s filthy and disobedient and refuses to answer me. Tell Ruth to scrub him with carbolic and give him some clothes. I want him presentable – and in a mood to answer when spoken to; if he refuses he will have no supper. You know that I mean what I say.’

‘Yes.’ Eliza’s eyes met hers. She knew all too well that Mistress Simpkins gained pleasure from punishing those unfortunate enough to arouse her ire. ‘I’ll find Ruth – what is the boy’s name, please?’

‘His name is Joe, so I am told, but he refuses to answer to it.’ Mistress Simpkins’ eyes gleamed. ‘You might tell him what happened to you, girl.’

Eliza met her gloating look with one of pride. If it had been Mistress Simpkins’ intention to break her by shutting her in the cellar her plan had misfired. The horror she had endured had just made her hate the warden more and she was determined to defy her silently, giving her nothing she could use to administer more unjust punishment.

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘I might …’

‘You impertinent little bitch!’ Mistress Simpkins raised her hand as if she would strike but Molly made a move towards her and something in her manner made the mistress back away. ‘Get off and do as I tell you or you will feel the stick on your back.’

Eliza ran off, leaving the clammy heat of the washhouse to dash across the icy yard to the kitchen. She knew that if Molly hadn’t been there to witness it, Mistress Simpkins would have struck her. Molly had some status in the workhouse. Eliza didn’t know what it was but she thought perhaps the master favoured her.