Полная версия

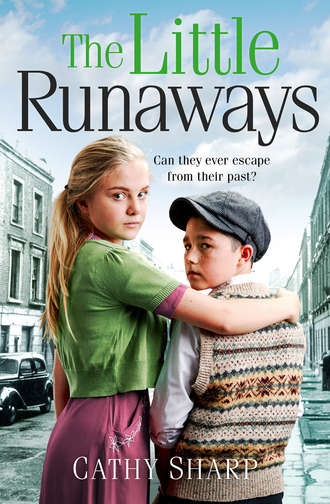

The Little Runaways

For a moment Angela’s eyes filled with tears, because the thought of her mother’s behaviour at Christmas still made her want to weep. She hadn’t come to terms with what her father had told her concerning her mother’s mental breakdown – because, of course, that was what it was. Mrs Hendry had always been a highly strung woman but something had changed her. In her right mind, her mother would never have stolen things from shops or drunk so much or run up a huge debt for her husband to pay.

When she saw him alone after returning to London, Angela had asked Mark if he knew why her mother was ill but if he did he hadn’t told Angela.

‘People sometimes become overwhelmed by life,’ was all he would say. ‘Something was triggered in your mother’s mind and …’ He shook his head. ‘If I understood why these things happened I would be able to do more for my patients. I believe it was a slow, gradual illness, made worse by the war and then …’ Mark had refused to elaborate. ‘I’m sorry, Angela, but I cannot reveal confidences.’

‘But she isn’t actually your patient.’

‘No, but your father is trying to persuade her to consult me – and she has talked to me in confidence.’

‘And you feel you can’t talk about it?’ Mark nodded and Angela felt annoyed with him. ‘I wish you’d let me know sooner that she was drinking too much. Perhaps I could have helped her.’

‘I doubt it,’ Mark said. ‘Even had you been living at home it would still have happened – it was already happening before you took the job at St Saviour’s. You’d had enough to bear with John’s death. I just wanted to spare you the pain of knowing for as long as I could. We hoped that she would conquer the habit. Instead, it has become very much worse. I thought she was much better at the dance she organised – but perhaps that was because you’d trusted her to do it. She is very proud of you, Angela.’

‘She never shows it.’ Angela shrugged the suggestion off. The fact that Mark had kept her mother’s addiction from her rankled more than she liked and she wasn’t ready to forgive him yet. She’d believed they might be getting closer to one another – but a man who truly cared for her would have known she was strong enough to face up to the challenge.

She put the thought from her mind, glancing round her apartment once more. She would have a house-warming party soon, Angela thought, going through to the modern and very new kitchen to boil a kettle. Yes, something simple would do; with a buffet if she could find anything nice in the shops.

‘I’m glad you’re here, Angela,’ Sister Beatrice greeted her as she walked into the sick bay that Sunday evening. ‘Nurse Paula has gone down with flu and rang to say she would be off work for the rest of the week.’

‘Oh, poor Paula,’ Angela said. ‘It is as well we’ve taken on Staff Nurse Carole.’

‘Yes, she has excellent references. We were lucky to get her – and that’s down to you, I suppose.’

‘Why down to me?’ Angela was surprised at the praise, faint though it was.

‘Yes, because of the extra funds you raised before Christmas, we’ve been allowed to employ another nurse with the necessary level of experience.’

‘Oh … well, yes, I suppose that did help but once the new building is finished we shall need more …’ Angela’s words were lost as they heard blood-curdling screams from the isolation ward next door. ‘What on earth was that?’

‘I think it must be Terry Johnson,’ Sister Beatrice said, ‘and that is why I’m glad you’re here this evening. We tried to separate him and his big sister, Nancy, into different dormitories earlier this morning, because they been here a couple of days and are obviously not carrying an infection, but the boy became violent and bit Staff Nurse Carole when she tried to part them. His sister intervened and he quietened, but he is going to need watching. We were forced to give him a mild sedative and leave them both in the isolation ward – but it sounds as though it has worn off.’ She hesitated, then, ‘I think Nurse will need help in there this evening.’

‘I’d better go and see whether he needs anything,’ Angela said, though the first screams had not been repeated.

‘I imagine his sister is calming him down, but they can’t be ignored. Go and talk to them, Angela, see what the matter is if you can. He won’t speak to me, I’m afraid. Usually, I can get children to talk, but not this boy. He just stared vacantly at me, though I’m sure he understood every word I said.’

‘Yes, Sister, I’ll see what I can do,’ Angela promised.

She left the sick bay and went through to the isolation ward. The dormitories were almost full in any case, because since Christmas six new children had been brought to the home and it was just about at bursting point. Angela knew that Sister Beatrice was impatient for the new wing to be ready, but although the builders had promised to be out by the end of this month, it looked as if they might not be finished for weeks yet. Angela would have to do what she could to hurry them up.

Entering the ward quietly, Angela saw a girl of slight build, perhaps thirteen or fourteen years of age, sitting on the edge of one of the beds. She had fine fair hair and was talking softly to the boy in the bed, stroking his much darker hair, her voice gentle and comforting.

‘Was it ’cos the door was locked, Nance?’ he asked, his eyes wide and scared. ‘I can’t remember … was it my fault … did I do something bad …?’

‘No, of course not, love,’ she murmured. ‘Pa was a brute – what he did to us both … He made it happen – it wasn’t your fault—’ Suddenly, she broke off and turned her head to look at Angela, a look of fear in her soft grey eyes. ‘Who are you?’

‘I’m Angela Morton. I work here, in the office, and sometimes help out with our children. I’ve been asked to see that you and your brother are safe and have all you need …’

‘Thank you,’ the girl said, and the fear in her eyes lessened, though Angela sensed hesitation in her. ‘Terry was having a bad dream – about our ma and pa …’

‘You’re Nancy, aren’t you?’

‘Yes, miss,’ she said, her eyes never leaving Angela’s face, almost as if she were trying to assess her, to see if she could be trusted. ‘I’m the eldest, almost fourteen. Terry is only ten; eleven in September. He’s usually as good as gold but …’

‘Yes, of course. We do understand what you’ve been through, Nancy. I hear you were a very brave girl. You should be proud of yourself for saving your brother’s life. It must have been terrifying to go back upstairs when the fire was raging.’

‘I had to, miss. It wasn’t his fault that the fire started – Pa was drunk. He must have knocked over the lamp and not noticed what he’d done. He was always getting drunk, miss, and Ma wasn’t much better. They locked Terry in his room and went out drinking together that night. Terry didn’t have any supper and he was crying but Pa had the key in his jacket pocket, and after they came back drunk, I unlocked the door and gave Terry a drop of tea and a crust of bread and jam … I was still in the kitchen clearing up the mess they’d made when the fire started. I heard Terry scream and went up and dragged him down the stairs. He just stood there staring …’

Nancy’s voice had risen, and she seemed on the verge of hysteria herself. ‘Terry shouted to Ma but their door was locked to keep us out and they either didn’t hear or they were too drunk … I couldn’t get them out, because the door was blazing – it was too late.’ Her voice broke on a sob of despair. ‘Too late …’

Angela could see that the girl was suffering from delayed shock herself. ‘It was a terrible tragedy, Nancy. No one blames you or your brother for what happened. You got your brother out, and you tried to save your parents too.’

Nancy’s gaze veered away, seeming to look into the distance. ‘Yes, miss, that’s what the policeman said. The firemen tried to get in but they couldn’t reach them; the stairs were all afire by then and no one could get to the bedrooms that way. When they got in through the window, they were dead from the smoke. We ran away because we didn’t know what to do – and Terry said Ma was screamin’ but I didn’t hear her. I think it’s just in his head, ’cos he loved Ma. It wasn’t our fault …’

Nancy was so intense. Angela reached for her hand and pressed it reassuringly. ‘I am quite certain it was not, Nancy. As you said, your father probably knocked his oil lamp over and didn’t notice because he was drunk. Fire spreads so quickly in old houses and by the time the fire service came it was too late. I am so sorry for all you and your brother have suffered.’

‘Yes, miss, thank you, miss,’ Nancy said and rubbed at her eyes. ‘I don’t want to lose Terry, miss. He’s all I’ve got now – and it’s always been the two of us …’

‘I’m sure you love him. He will be quite safe with us, I promise you. In time he will stop being so afraid and then he will realise that we are here to help children who have lost their homes. Do you have any other relatives?’

‘No, miss, not that I know of. They mostly died in the Blitz. Me ma once spoke of her cousin in the country, but she never come to see us …’ Tears welled in Nancy’s eyes. ‘Ma didn’t deserve to die. She did what she could for us until she got bad. Pa spent all he earned on drink and she gave us most of her food. I wanted to save her, miss. Truly I did, but the flames were so hot I couldn’t get near the door …’

Angela handed her a clean white handkerchief. ‘Wipe your eyes and blow your nose, Nancy. I am quite sure you did what you could for your mother and your father. It isn’t your fault. They were the adults; it was their job to keep you safe in your own home – no one will blame either of you.’

‘Will that Sister Beatrice let us stay here if Terry keeps screaming and being wild? She was very cross when he fought the nurses who tried to give him a bath. The only person he trusts near him is me.’

‘Why is that, Nancy?’ Angela asked, but the girl just shook her head. Clearly she didn’t want to talk about it, and it was too soon to press for details, although Angela suspected that the bruises on Terry’s body might have been inflicted by his father and not a tramp. No doubt Nancy would tell them the truth when she was ready.

‘I’ve always cared for him.’

‘The nurses have to make sure you don’t have anything infectious when you come – but perhaps Sister will let you stay here in this ward until he is more himself.’

‘Will you ask her if we can stay here together, miss? Sometimes, he wets the bed, and he walks in his sleep. If I’m not there to take him back to bed he might … hurt himself.’

‘Yes, I can see that,’ Angela said. She thought privately that Terry was a very disturbed child and might benefit from Mark Adderbury’s attention. Mark specialised in helping mistreated children in his spare time from his busy practice. Sister Beatrice relied on the help and advice he gave freely. ‘I’m sure you can stay in here for a while, just until we can sort something out …’

‘Thanks, miss. You’re kind.’ Nancy sniffed into the handkerchief and then offered it back.

‘You keep it for a while; you must have lost everything in the fire. I know St Saviour’s provides new clothes, but is there anything I can get for you that you need?’

‘Terry had a teddy bear he used to take to bed, but it was left behind when we escaped. It might have helped him to sleep …’

‘I can’t give him back the one he lost, but I do have my own very old and much-loved bear, if you think he would like that?’

‘You’d really let us have it?’

‘Yes,’ Angela said. ‘I’ll bring it tomorrow – and I’ve got a few pretty things you might like, Nancy. A case to put hankies in, and a brush and comb for your hair – and some satin ribbon to tie it up. You’ve got nice fair hair and it curls naturally.’

Nancy blushed, the tears glistening on her lashes, but she didn’t cry. Terry had been lying in the bed, just staring up at her, but now his eyes closed and Nancy smiled.

‘I think he will sleep now, miss. Shall we see you tomorrow?’

‘Yes. I shall be in and out this evening, just to make sure you’re both all right. I can get you a mug of cocoa to help you get off to sleep if you like?’

‘No, miss, I’m all right. I’m going to get into bed with Terry so that if he wakes again he won’t start screaming and wake everyone.’

‘Well, make sure you get out before the morning staff come on duty – they might not approve of you sleeping in his bed.’

Nancy looked at her sadly, reflecting more knowledge than ought to be in the eyes of a girl of her age. ‘I know, miss, but our Terry wouldn’t hurt me: he isn’t like Pa …’

‘Nancy.’ Angela caught her breath in shock. ‘Your father didn’t …?’

Nancy’s eyes filled with suffering but she didn’t say anything. Angela couldn’t bring herself to ask the questions that hovered at the back of her mind. If her suspicions were correct, Nancy had been interfered with by her own father and she was less than fourteen years old. What kind of a man would subject his own daughter to something so vile? He had more than likely beaten his son as well. She couldn’t help thinking that neither Nancy nor her brother would mourn him, though both seemed to be upset over their mother.

Angela left the children to sleep, but she couldn’t put the look in Nancy’s eyes out of her mind. Perhaps it was an act of fate that had caused the fire and set them free – and yet Angela had an uncomfortable feeling that there was much more that Nancy could have told her had she wished.

The problem was, what ought she to do about it? She supposed she should report what Nancy had let slip to Sister Beatrice, who would no doubt inform the police – but what was the point of that? Nancy hadn’t really told her anything and it could lead to lots of questions for the girl, and she’d already been through so much. She’d trusted Angela enough to open up a little and it would be a betrayal of that trust to tell. For the moment Angela would keep her suspicions to herself. What harm could that do?

SIX

Carole looked at herself in the rather mottled mirror on the wall of her room at the Nurses’ Home and patted her natural blonde and very short hair with satisfaction. It was important to keep hair clean and neat for work, and her new fashionable boyish crop suited her. She was pleased with herself for finding this job. After completing her training at the London Hospital, in Whitechapel, she’d wanted a change, somewhere that she could influence her own life.

The Sister in charge of her ward at the teaching hospital had disliked her almost from the start and Carole was fed up with being picked on the whole time. She was an excellent nurse and had passed all her exams easily, and yet Sister Brighton seemed to hate her. That was probably because Dr Jim Henderson had taken an interest in the younger nurse, and everyone knew that Brighton was mad about him. Unfortunately, he hadn’t looked at her and it had turned her sour – at least, that was what all the nurses under her supervision thought.

For a while Carole had believed that Jim Henderson was the right man for her. Yes, she had imagined being a doctor’s wife and all of the perks that it would have brought. But he had been too dedicated to his job for Carole’s liking, neglecting her to work all hours and talking endlessly of going overseas for a few years to work in a mission hospital and taking her with him to do his charitable works. That was the last thing she’d wanted. Besides, she wasn’t in love with him; there had been a man once, but he had died on the beach at Dunkirk … Carole had hardened her heart after that and now she kept her distance. If she did marry it would be because it fitted in with her plans for a good life – and that didn’t include being a missionary’s wife in some godforsaken backwater. Once the romance was over, she’d given in her notice and taken this job. She was glad to see the back of Henderson and Sister Brighton; they were welcome to each other as far as she was concerned.

At least here she didn’t have to share a room any more. One day she’d have her own little flat, but this would do for now – besides, if you had your own place men tended to ask if they could come back for a drink when what they really wanted was something more. Carole wasn’t a complete innocent, and she would have gone to bed with Jim if he’d shown more interest in her sexually … but he was too intent on his good works. Next time, she would choose a man who was more worldly …

St Saviour’s had exactly what she was looking for. The atmosphere was more relaxed than at the hospital, though Sister Beatrice was a bit of an old dragon. She breathed fire and brimstone whenever she considered someone had done something wrong, but Carole knew her standards were excellent and the nun would be unlikely to find fault with her work. If she’d guessed what was in Carole’s mind, well, it was doubtful that she would ever have taken her on.

Men were unreliable and selfish, and apart from using them to further her ambitions, Carole was opting to focus her efforts on building her career – in her own way. Sister Beatrice was getting on a bit and old-fashioned. An intelligent nurse such as herself could work hard and find a way to make herself indispensable so that when the old harridan retired in a few years she would be the natural successor.

Carole fixed her cap at the precise angle, smoothed her uniform and left her room, locking the door behind her.

It was chilly as she walked to the children’s home through the connecting gardens. St Saviour’s was almost unique in having more than a back yard in this area of London, but it was a relic from the past, when the house had been an impressive early Georgian mansion – and then later a hospital for contagious illness. Similar buildings had grown up all round as the area was peopled with silk merchants, and then the Jewish immigrants who had taken over the streets around St Saviour’s when the rich merchants had moved up West. The house had been used as the old fever hospital until it was closed in the early 1930s, but since then many of the Jewish synagogues and shops in the area had been replaced and there was a mixture of cultures and peoples working and living in the narrow dirty streets. St Saviour’s had become a home for children in need during the war, and the house the nurses occupied was what had once been a rather grand home for the Warden of the fever hospital.

Carole was surprised that the buildings here had survived the bombing in the war. The surrounding streets were filled with large empty spaces overgrown with weeds and neglected, awaiting renovation. In Bethnal Green several bomb sites had been turned into gardens and small allotments for the local residents; here the ruins were just left to decay while local children made a playground from the ruins of their former homes. The Government was going to build houses and shops to replace those lost in the war, but because of the shortage of building materials they were instead putting up prefabricated bungalows and they were dotted here and there amongst the decay and destruction; some had been built further out from the centre, where the air was fresher. Londoners were starting to drift out to the suburbs with the promise of new homes and a better life. From the outside St Saviour’s looked grubby like the rest of the buildings in the area, though inside it was as clean as Sister Beatrice could persuade her staff to keep it.

Most of the girls here were all right. She quite liked Staff Nurse Michelle, though she hadn’t seen much of her, but she was an East End girl and didn’t seem a threat to Carole’s ambition. Angela Morton was a different matter; she wasn’t sure whether she liked Mrs Morton or not, because although she was always friendly there was something about her – something that made Carole sense a rival.

Carole hadn’t yet worked out what Angela’s role was here. She talked of herself as being the odd-job lady, but she carried authority, speaking with a confident smile and amusement in her eyes. Everyone seemed to like her – at least Nan spoke very highly of her and Sally Rush seemed to think she was wonderful. Nan was a surrogate mother to the children, helping with everything, from washing them to giving them hot drinks in the night, taking them to the toilet if they couldn’t manage, or out on school trips. She was the lynchpin of the home and she seemed to be in Sister Beatrice’s confidence. But Nan wasn’t an ambitious person and wouldn’t think of herself in the position of Warden – though Angela Morton might.

Yes, she would bear watching, Carole thought as she let herself in through the back door and went along the rather dark corridor to the dining room, where breakfast was still being served. Helping herself to coffee and a piece of toast with a scraping of what looked suspiciously like margarine and a spoonful of marmalade, she sat down at the table reserved for nursing staff.

Most of the children had already eaten and were leaving the tables in an orderly fashion, under the eye of some of the senior children: new monitors that Angela had appointed since Christmas, so Carole had been told. Sally Rush was gathering the smaller ones, preparing to take them to wash their hands and jam-smeared faces. She saw Carole and nodded to her in a friendly way. Sally was all right; Carole had already marked her down as harmless.

Carole glanced at the little silver watch pinned to her uniform. She had another fifteen minutes before she was due on duty, but she might as well go up to the wards and look in on the new arrivals. Being early for work was always a good way to impress and she wanted Sister Beatrice to think well of her, because she knew she was still on probation as far as the crusty old nun was concerned. She was wed to her order and her religion and had probably never had a man in her life; at least that was Carole’s guess. Her whole life revolved around St Saviour’s and the children. Carole would never be like that; even if she did stay on to become Warden, she would never let her job become her whole life. No, she wanted it all and she intended to get whatever she could out of her present position.

Patting her mouth with the napkin, she stood up and straightened her uniform and then walked briskly from the dining room, almost colliding with a young red-haired boy who was running as if his life depended on it. She grabbed hold of his arm to steady him as he almost fell over in his efforts to avoid knocking into her.

‘Sorry, Nurse,’ he said. ‘I was in a hurry to catch up with Mary Ellen – you won’t tell on me, will you?’

‘You must be Billy Baggins,’ Carole said with a frown. ‘I’ve heard about you. You’re the little rebel. You really should start looking where you are going, but no, I shan’t tell on you – this time; just don’t do it again.’

‘Thanks, Nurse.’ Billy grinned cockily and walked nonchalantly away.

Carole guessed he would run as soon as he was out of view, but why should she care? She smiled, because she was a bit of a rebel herself and always had been. Perhaps it came from being the youngest of a clever brood and always the last to know what was going on in the family home. Not that she had much family now: the war had seen to that, taking her father and two elder brothers and leaving her with just her sister, Marjorie, and her mother.

Just as she reached the top of the stairs she saw a man come from Sister Beatrice’s office. He walked towards her, stopping to smile as they came face to face outside the sick bay, and then he offered his hand. Carole noticed at once that his hand was strong and assured as he clasped hers firmly; on the little finger of his right hand he wore a solid gold signet ring.

‘I’m Mark Adderbury,’ he said. ‘You must be Carole Clarke, the new staff nurse. Sister Beatrice told me about you. I’m glad to meet you, Carole.’

‘Yes, I’ve heard a bit about you too.’ Carole gave him the special smile she reserved for men who passed the test, and he did with flying colours. Good-looking, mature, rich and intelligent, he had all the necessary qualities – but what was he like as a man? ‘You visit the disturbed children, I think?’

‘Yes, that’s my job, but I’m interested in everything that goes on here and all the children. St Saviour’s gives hope to children who had none when they were brought here, Carole. I think helping a place like this to exist is the best job in the world.’