Полная версия

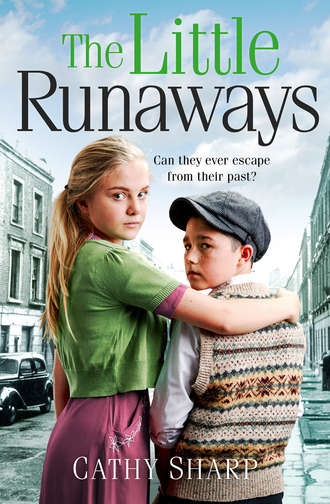

The Little Runaways

Alice didn’t know their Administrator well, but she admired her for standing up to Sister Beatrice when Mary Ellen had been banned from going to the pantomime. Alice had never been to one as a child, and she knew how much it would mean to a kid from a poor home like her. It was rotten to take the best treat away from the girl and Alice had been on Angela’s side when she took Mary Ellen to the pictures when the other kids were at the pantomime. Alice didn’t know, of course, but she’d bet Sister Beatrice had had a few words to say about that!

Angela smiled and spoke whenever they met and she knew she was very friendly with Sally – but would she be sympathetic if Alice told her what a mess she was in? Angela could have no idea of the sort of family Alice came from so perhaps she would be like Sister Beatrice and take the moral ground. After all, she probably had a perfect family life at home and would think Alice a stupid girl who was no better than she ought to be.

Angela stared at her father in disbelief as he showed her the things he’d taken from her mother’s wardrobe. Besides a lot of empty gin bottles, there was an assortment of dresses, handbags, perfume, soaps, scarves and hats – and many of them were stolen, according to her father.

‘But why?’ she asked. ‘Why would Mother take things like this? The clothes wouldn’t fit her or me – it doesn’t make sense.’

‘I asked Mark about it and he said that she’s ill, Angela. Sometimes when she’s had a few drinks she goes out and takes things from shops: local shops, where we have an account. That’s how I found out about it. One of the managers telephoned me from his office in private; he didn’t want to go to the police and asked me to discover whether she still had the things she’d stolen. Of course when I found all this – I didn’t dare to ask if it all belonged to him. I simply arranged to pay for the items he’d lost, and then he asked if I would care to settle the account.’

‘Was it very bad?’ Angela asked, noticing the new lines about his eyes. No wonder he’d been looking worried the last few times she’d seen him. ‘I can help with money, of course.’

‘I’m all right for the moment,’ he said. ‘I’ve cancelled the accounts in her name and closed the joint account at the bank. I didn’t want to humiliate your mother, Angela – but I couldn’t let it continue.’

‘So the drinking isn’t the worst of it, then.’ Angela reached across the kitchen table to squeeze his hand. ‘I’m truly sorry – but what can we do? She needs help …’

‘Mark says there is a very good clinic in Switzerland that would help with all her problems – the only trouble is your mother will not hear of it. She insists that nothing is wrong with her and said she hadn’t realised she’d run up large bills and promised not to do it again.’

‘What about the stolen stuff?’

‘She absolutely refuses to acknowledge that she took anything.’

‘It makes things so difficult for you, Dad. What are you going to do?’

‘I can’t force her to go away. She is my wife and I must try to protect her as best I can. I’ve told her she can’t use the car in future and the bus only goes into town twice a week. I’ll try to make sure she doesn’t catch it unless I can go with her – what more can I do?’

‘I don’t know,’ Angela said. He’d closed his eyes, as if he found the worry almost unbearable. ‘What about you? Are you all right?’

‘Just a little tired,’ he said, but she had the feeling that he wasn’t telling her everything. ‘I’ve seen my doctor and he advises cutting down on work.’

‘You must try not to worry. If you need me I could come down at a couple of hours’ notice. You know I would stay if you thought it would help.’

‘I don’t think she would take any notice even of you, Angela. I had hoped that she would make an effort for Christmas – as she did for the dance she organised for your charity.’ He sighed deeply. ‘She used to have good days and I kept hoping – but her drinking is getting worse. She would only drink sherry or wine once, but now she will drink whatever she can get.’

‘I wish I could do more.’

‘Just being able to tell you has helped a lot,’ he said and smiled. ‘Mark has offered to advise her but so far she just refuses to listen.’

‘I see …’

Angela turned away to pour more coffee, distressed by the news of her mother’s illness. Mrs Phyllis Hendry was the last person to drink to excess or steal from shops – at least she always had been. Angela couldn’t imagine what had happened to change the rather snobbish, intelligent woman she loved but couldn’t quite like, into this person who drank too much and stole things. Yet Mark’s attitude had distressed her more – or perhaps hurt was a more apt word. Yes, she was hurt that he’d decided he couldn’t tell Angela in case it made her break down. Had he thought she would turn to drinking like her mother?

She felt a little diminished, too. She’d turned to Mark in her grief over John’s terrible death, sobbing out her pain on the shoulder he offered – but now she felt patronised. When he’d suggested the job at St Saviour’s she’d thought he trusted and respected her – but if he felt anything for Angela, he would not have hidden her mother’s secret from her. There was little Angela could do here, it seemed, but at least she could offer her father support.

‘If you need me – anything, you have only to call, Dad.’

‘Yes, I know,’ he said. ‘Now go up and talk to your mother. She’s feeling a little fragile – and ashamed. Try to make peace with her before you leave, my love.’

‘Yes, of course,’ Angela said and kissed his cheek. ‘I do love you, Daddy.’

‘I love you,’ he replied. ‘You’re the light of my life and always will be. Please don’t worry. I’ll manage somehow. Perhaps in time she will agree to go somewhere they can help her …’

FOUR

‘I’m cold, Nance, and ’ungry,’ Terry sniffed, and wiped his dripping nose on his coat sleeve. ‘When are we goin’ ’ome?’

‘We can’t go home, love,’ Nancy said, and put her arm round his thin shoulders, pulling him close in an effort to inject some warmth into them both.

‘Why not?’ He tugged at her arm. ‘I want me ma …’

‘Don’t you remember what happened?’ she asked him. Terry shook his head and Nancy bit her lip, because he surely couldn’t have forgotten the terrifying events that had led them to flee the house as it was burning. Nancy had such terrible pictures in her head of the door of their parents’ room. It had been blazing by the time she’d reached the landing and saw her brother staring wide-eyed at the door. She’d known immediately that it was impossible to reach them, and as Terry started to scream, Nancy had seized him and pulled him down the stairs, grabbing coats and a hunk of bread that had been left on the table earlier. There just hadn’t been time to bring anything else; besides, there was never much food in the house.

‘We shan’t talk about it then, Terry.’ What was she going to do? Nancy hadn’t thought past their escape from the fire, but now after several days hiding in a disused shed on the Docks, and eating only the scraps of food that she could beg from a night watchman, she was beginning to realise they couldn’t stay here for much longer.

‘Nance, me stomach hurts …’ Terry whined, and rubbed grubby fingers at his face. ‘I want ter go ’ome …’

‘Shush … someone is coming,’ Nance hissed at him. She clutched hold of her brother’s arm as the door was opened and a large man in working clothes entered. She’d thought no one came near this place, and that they were safe from discovery because the Dock workers were still having their Christmas break. ‘Let me do the talking, Terry. Don’t say anything but agree with whatever I say.’

‘What ’ave we got ’ere then?’ the man said, and frowned as Nancy pushed her brother behind her.

‘We’re not doing any harm, mister,’ she said defensively. ‘We’ve got nowhere to go …’

‘Why aren’t you at ’ome?’ he asked, and then his frown cleared. ‘I reckon you’re them kids the coppers ’ave been lookin’ for … the ones whose folks got burned in the fire.’

‘What’s ’e mean, Nance?’ Terry pulled at her arm and she saw a flicker of fear in his eyes. ‘Where’s Ma? What’s ’e mean they got burned?’

‘My brother doesn’t remember anything, mister,’ Nancy said, though she remembered all too well. ‘We didn’t know what to do when we ran away … it all happened so fast. We had to leave quick and I couldn’t help them …’ A choking cry broke from her. ‘I had to get Terry out …’

‘Yes, o’ course yer did,’ he said soothingly.

‘I didn’t know where to go …’ Nancy was poised ready to flee, though she knew there was nowhere she could go, because they were both filthy, cold and near to starving.

‘Well, I reckon the coppers will know what to do,’ he said gruffly and kneeled down beside them. ‘You can’t stay here or you’ll freeze – tell me, ’ave yer had anythin’ ter eat today?’ Nancy shook her head. ‘You come along of me then, and I’ll sort yer out … no need to be frightened, nipper. I ain’t goin’ ter ’urt yer.’ He reached out towards the boy.

Terry pulled back from the man, looking wildly from side to side, as if he wanted to escape, but Nancy took a firm hold on his arm. ‘Come on, love,’ she said. ‘We haven’t got a choice. You’ll be all right, I promise.’

‘Constable Sallis won’t ’urt yer,’ the man said. ‘I reckon as he’ll be right glad ter find yer …’

‘Well, here you are then, Sister, our little runaways,’ Constable Sallis said. ‘I told you the other day that we feared the pair of them might be dead in the fire, but they’d run away because they were frightened and they were found down at the Docks, hiding in one of the sheds. One of the Dockers discovered them late yesterday afternoon on his way home and brought them to the station. We’ve kept them there overnight.’

‘What are their names?’ Sister asked, glancing towards the children, who were at that moment being cared for by Nan, St Saviour’s head carer.

‘Terry and Nancy Johnson,’ he replied. ‘Amazingly, neither of them was burned or had any ill effects … well, not physical. The boy seems terrified and screamed when I tried to touch him earlier, but that is natural enough. The girl is older and she says she was in the kitchen when she smelled smoke. She rushed upstairs to find her brother and dragged him out of bed and downstairs, and finally out of the house through the back yard – that’s why he’s in his pyjamas and his mother’s coat …’

‘We’ll soon sort them some clothes out,’ Sister Beatrice said. ‘How long were they missing?’

‘Well, the fire must have started some time on New Year’s Eve – and here we are 9th of January. I think one of the night watchmen gave them some food. They weren’t lost long enough for them to become really ill or to pick up lice anyway.’

‘I dare say they need a nice bath and some good food,’ Sister said. ‘You did right to bring them straight here, Constable. We’ll look after them now.’

‘I’ll get off then,’ he said. ‘It’s bad news about their parents – the fire started in a locked bedroom and neither of them got out, I’m afraid. Terrible time of year to find themselves orphans and homeless, isn’t it?’

‘I doubt it matters what time of year something like that happens,’ Sister said wryly, and he shook his head as he went off.

Sister Beatrice went over to Nan. ‘I’ll just take a look at them and then you can pop them in the bath … the boy first …’ Nan turned to try to help Terry get undressed, but he kicked out at her and backed away, his eyes rolling wildly.

‘Don’t yer touch me …’

‘You have to be examined and then have a bath,’ Sister told them. ‘It’s just routine, Terry.’

‘Nance, don’t let them ’urt me,’ he cried, and clung to his sister.

‘It’s all right, love,’ his sister said. ‘We’ve got to do what they say for now, Terry – and they won’t hurt you.’ She turned to Nan with a look of appeal in her eyes as she removed the coat and pyjama top. ‘Please, let me help him. He’s used to me.’

‘If you wish,’ Nan said, ‘but Sister needs to make sure he doesn’t have …’

Her words were left unfinished as she saw the marks on the child’s torso where he had obviously been beaten recently.

‘Who did that to him?’ Sister asked, shocked by the sight of his thin body and bruised flesh. She’d seen children in this condition often enough, but this was a particularly severe beating by the looks of it.

‘No one,’ Nancy said quickly. ‘He fell over and hurt himself – at the dockyard, after we ran away because of the fire.’ Nancy looked at Terry urgently. ‘That night I sent Terry to bed with a hot drink and then I went down and cleaned the kitchen … and then I smelled the smoke …’ She caught her breath and put her arms protectively around her brother. ‘Everything was blazing upstairs. I just grabbed him and we ran away …’

‘Yes, so Constable Sallis told me,’ Sister said. ‘Well, that was a brave thing to do, to go upstairs to rescue your brother when the fire must have been very strong – so I suppose you can be left to bath him. Just let me look at you, child. I promise I shan’t hurt you.’

‘You’re quite safe here,’ Nan told him, and looked kindly at Terry as he reluctantly submitted to Sister’s brief examination.

‘Caught you!’ Sally Rush gave a little scream and turned swiftly as she felt the hands on her waist. She was looking into the face of the man she loved but had not seen since Christmas Eve. He’d gone out of London for the festivities but she’d expected him back several days ago and been disappointed that he hadn’t kept his word to take her somewhere nice when he returned. ‘I’ve missed you, Sally,’ Andrew Markham said, and snatched a quick kiss on the mouth. ‘Any chance you missed me?’

A pretty girl with reddish brown hair cut short to form little flicks about her face, and melting chocolate eyes, Sally couldn’t help a smile peep out at him. She’d been feeling annoyed because he hadn’t contacted her in the New Year as he’d promised, but he was so attractive with his light brown hair and gentle smile, so the slight feeling of hurt melted away in her pleasure at seeing him.

‘Oh, Andrew, you know I did. I thought you would be back in London days ago …’

‘I intended to be,’ he said, and his smile dimmed. ‘Forgive me, darling Sally. My aunt had a bit of a turn and I had to take her into the hospital. She is over the worst, thank God, but she will need to stay in a nursing home for a few weeks.’

‘Oh, I am so sorry,’ Sally said. ‘I hope she isn’t really ill?’

‘Her heart isn’t strong,’ he said. ‘The specialists say she may have a few years yet. I must hope so. Aunt Janet brought me up after my parents died and I’m fond of her. I have to look after her now – as she did me.’

‘Yes, of course you must,’ Sally said, giving him a loving smile. ‘It was just that I missed you.’

‘Had you been on the telephone I would’ve called, but telegrams only ever carry bad news and I didn’t want to scare you, hence the surprise.’

‘You certainly did that,’ she said, her cheeks warm because Nan had just entered the playroom. ‘Did you want me, Nan?’

‘I need you to help me with a couple of new arrivals,’ Nan said.

‘Yes, of course,’ Sally said, and turned to Andrew. ‘Shall I see you later?’

‘I’ll call for you at home at half past seven.’

Sally nodded and turned to Nan as they went into the hall together. ‘Who have they brought in for us today?’

‘It’s a brother and sister. Their names are Nancy and Terry Johnson. They both seem nervous – the boy is terrified, I think. The police have been looking for them, as they were missing after their home caught fire, and found them hiding down the dockyard. Unfortunately, the parents were killed but the children got out somehow and ran off in fright … I suppose that is natural enough. It must have been terrible.’

‘It’s a miracle they got out, isn’t it?’

‘Constable Sallis thinks the girl pulled her brother out of bed and they fled, not knowing what else to do.’

‘Poor little things,’ Sally said. ‘How old are they?’

‘I think Nancy must be nearly fourteen and her brother …’ Nan frowned. ‘I’m not sure, because he looks as if he might be ten or so but seems backward for his age. I left him with Michelle. She was giving them a little check over when I left …’ Nan’s words were cut off by the sound of screaming from the bathroom. They looked at each other and Sally broke into a run, arriving just in time to see the boy sink his teeth into Michelle’s hand.

‘No, stop that, child!’ Nan cried as she followed her into the room. ‘You mustn’t bite. It isn’t nice …’

‘Has he drawn blood?’ Sally asked the staff nurse. ‘Shall I put some disinfectant on for you?’

‘The skin isn’t broken,’ Michelle said with a wry look. ‘Terry objected to my trying to take his pyjama bottoms off – didn’t you, Terry?’

‘Don’t like you,’ the boy muttered sullenly. Sally could see what Nan meant because he was nearly as tall as his sister, thin and wiry, and he looked quite strong, but his attitude was that of a small child. ‘Shan’t be washed. Nancy washes me – don’t yer, Nance?’

‘Yes, Terry, love, I look after you.’ Nancy came forward and placed herself between Michelle and the boy. Her eyes were filled with a silent appeal as she said, ‘Terry relies on me. I’ll give him a wash if you let us alone for a while.’

‘Staff Nurse Michelle wants to help you,’ Nan said. The children often resented the implication that they might have nits, but many of them were crawling with lice when they first arrived, and these two had been living rough, although if Constable Sallis was right, only for a few days. ‘No one is going to hurt either of you, Nancy, but you must have a bath – you may wash him if that is what you both wish.’

Nancy stared at her defiantly for a moment, and then inclined her head. ‘I’ll take your things off, Terry. Nurse has to look at us both but she won’t hurt you. I’m here to protect you.’

His sullen expression didn’t alter but he allowed Nancy to take everything off. Nancy turned him round so that they could see his thin body and Sally caught her breath as she saw the bruises all over his back, arms and legs.

‘Who beat you, Terry?’ Nan asked, but he just stared at her. She looked at Nancy, who hung her head but then mumbled something. ‘Speak up, my dear. We want to know who did this to your brother. It wasn’t just a fall, was it?’

‘It was a tramp where we were hiding,’ Nancy said, contradicting her earlier statement. ‘He was drunk. I pushed him over and we ran off and hid somewhere else – didn’t we, Terry?’

The boy nodded his head, seeming almost dazed as if he wasn’t sure what was going on. Sally suspected Nancy was lying to them, but if she didn’t want to tell them the truth there wasn’t much anyone could do.

‘I’ll leave you two to get on,’ Nan said, and went out.

‘Shall I show you how to run the water?’ Sally asked, leading the way to the old-fashioned bath at the other end of the large room. ‘Have you ever used a bath like this, Nancy?’

‘No, miss,’ Nancy said, staring at it. ‘We brought in a tin bath from outside when we had a bath – but we mostly just had a wash in the bowl in the kitchen, miss.’ She stared at Sally and then back at Michelle. ‘Are you all nurses?’

‘I’m a carer and my name is Sally. Nan is the head carer and she looks after us all. She is very kind, Nancy. You can trust her – and all of us. You’ve been brought here so that we can look after you. Once you’ve had a wash you’ll go into the isolation ward for a while, and then Sister Beatrice will decide which dormitories to put you in.’

‘What are they – dormitories?’

‘It’s another name for bedrooms. The girls go one side and the boys another.’

‘No!’ Nancy was startled, a frightened look in her eyes. ‘Terry can’t be separated from me in a strange place. We have to be together … please, you must let us. He won’t sleep and he’ll be terrified. Please, Sally, help us to stay together.’

‘I’ll talk to Nan about it,’ Sally said, ‘but I’m not sure what I can do – we’ve always separated the boys from the girls.’

‘Don’t tell Terry yet. Ask first, because he’ll get upset,’ Nancy begged.

‘Yes, well, you’ll be together for a while anyway. So I’ll see what Nan says. Now, I’m going to stand just here to make sure you can manage everything. If you need help, you only have to ask …’

Angela heard someone call her name as she walked towards the main staircase of St Saviour’s later that morning and paused, smiling as she saw it was Sally. She liked Sally very much because she was the first person to make her feel welcome at St Saviour’s when she’d arrived, feeling very new and uncertain just a few months earlier. Her friend looked happy and cheerful, even though her rubber apron was a bit wet and she’d obviously just come from bathing one of the children.

‘New arrivals?’ she asked, with a lift of her fine brows.

‘Yes, brother and sister,’ Sally said and sighed. ‘They were in a fire. I understand their parents died of smoke inhalation before the fire service got there.’

‘Oh, how tragic,’ Angela said. ‘Only a short time after Christmas and already we have another tragedy.’

‘Terry seems to be in a traumatised state. We couldn’t do anything with him but, fortunately, he does whatever his sister tells him so we’re getting by, so far.’ Sally frowned. ‘The boy has a lot of bruises. He looks as if he’s been beaten pretty severely recently. His sister said he’d had a fall and then a tramp had attacked him, but I think she was lying.’

‘At least he is safe now. He won’t be beaten here.’

‘No.’ Sally beamed at her. ‘It’s good to know he is safe with us …’ She hesitated, then, ‘Have you moved into your apartment?’

‘I got the keys two days ago and much of the stuff my father is sending up is coming later today. I have to meet the removers at around two o’clock so I’d better get going − I have a lot of work to do first.’

‘Perhaps I’ll see you tomorrow?’

‘I’ll be here later this evening. I’ve arranged to help out with the night shift.’

‘I’ll have finished my shift by then. Andrew is taking me out soon. We’re going somewhere special.’

‘Andrew Markham?’

‘Yes …’ Sally’s cheeks were flushed. ‘We’ve been going out since before Christmas, but just casually. It’s going to be different now, I think.’ She paused. ‘You did once say I might borrow a dress sometimes, if you remember?’

‘Yes, of course, Sally. Pop round tomorrow evening – say about eight? I’ll can show off my new home and you can choose something.’

‘I wouldn’t ask, but Andrew mentioned taking me to the theatre and I don’t have anything suitable. Mostly, I can wear my own things, but …’ She stopped and blushed, embarrassed at having to borrow Angela’s clothes.

‘Sally, I’d happily lend you anything of mine. I should have remembered my promise before this, but I haven’t stopped since we came back after the holidays.’

‘I don’t think any of us have had a spare moment,’ Sally said. She looked shyly at Angela. ‘I don’t want to let him down, you see.’

‘You couldn’t do that,’ Angela assured her. ‘You’ll look wonderful whatever you’re wearing.’ She glanced at her watch. ‘I must fly or I shall never get there.’

‘Go on, you don’t want to be late,’ Sally called after her but Angela didn’t stop to look back.

FIVE

Angela looked around the spacious sitting room with satisfaction. She’d been lucky to find an apartment of this size so close to her work at St Saviour’s, and after hours of moving furniture about and hanging curtains, she was finally happy with the effect. From outside, the building looked almost shabby, in keeping with its situation near the river and the old warehouse it had been some years before the war. During the bitter war that had wreaked so much havoc on the East End of London, it had sustained some fire damage but remained structurally sound. The building had since been restored to become a block of flats, some of which were quite small and others, like Angela’s, large with rooms big enough to hold her beloved piano and her gramophone, both of which had now been brought up from her father’s house in the country. Besides the large, comfortable sofa and chairs, and a selection of small tables, there was also a pretty mahogany desk and an elbow chair set near the picture window. Above her head, a wintry sunshine poured in through the skylights. Angela had fallen in love with it as soon as she walked in even though it had cost her more than she’d intended to spend on her new home. Her mother would think it an extravagance if she’d asked her, but her father had told her to go ahead and buy with confidence when she’d asked his advice.