Полная версия

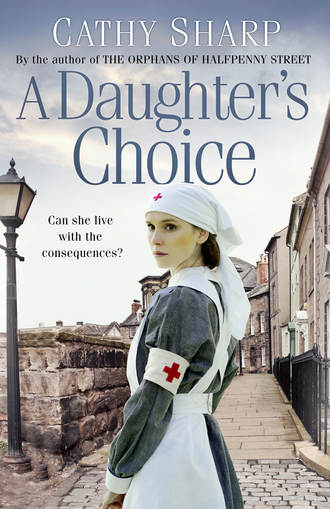

A Daughter’s Choice

‘I’m not your girl!’ I glared at him. ‘You don’t imagine I’d go out with you again after that?’

I started to walk away from him. I was smarting because of the insulting way Sam Cotton had behaved towards me, and also Valerie Green’s remarks about Billy. She was a year or so older and I’d known and liked her at school; it pricked my pride to know she thought me a fool for going out with him, especially as I had a sneaking suspicion she might be right.

Billy followed behind me. ‘Don’t be like this, Kathy. I’m sorry the evening was spoiled, but it wasn’t my fault. Sam Cotton is a docker. He couldn’t join up because they said he was needed on the docks – and some of us called him a coward. He hates anyone in uniform, especially me. That’s why he went after yer like that.’

‘He implied my mother was …’ I choked back a sob.

‘Don’t matter what she were,’ Billy said swiftly. ‘You ain’t like ’er, Kathy, and any man with sense knows that. Don’t be mad at me. I only did it fer you.’

I stopped walking and looked at him. ‘Was she a tart – my mother? Tell me the truth, Billy. I really need to know.’

‘I remember talk when she married your da …’ Billy frowned. ‘I were only a lad and me best mate were ill. Tom O’Rourke went away about that time and I were angry at the world because I thought he were goin’ ter die. I didn’t take much notice of anythin’ else, but I know me ma thought Ernie Cole was a fool to marry ’er. Sorry, lass. I can’t tell yer much more. Ma knows it all but whether she’d tell yer …’ He shrugged his shoulders. ‘I shouldn’t let it worry yer, Kathy. No one who knows yer thinks you’re like that.’

I looked at him unhappily. It wasn’t Billy’s fault that the unpleasant incident with Sam Cotton had happened. He had defended me and I supposed I ought to be grateful.

‘You shouldn’t have kept on hitting him like that, Billy. I thought you were going to kill him.’

‘I might ’ave if they ’adn’t dragged me off ’im,’ he admitted. The look in his eyes told me he wasn’t quite so proud of himself now. ‘He made me see red, Kathy. No one treats you like that when I’m around.’ He reached out and stroked my cheek with the tips of his fingers. ‘You’re special to me. Don’t you ever forget that.’

‘Oh, Billy …’ I was moved by something in his voice and manner and didn’t resist as he bent his head and gently kissed me. It was just a brief touch of his lips against mine but it made me feel odd. ‘Please don’t, Billy. Not yet. I’m not angry with you now, but I don’t know how I feel. I’m not ready to think about—’

He placed a finger to my lips. ‘’Yer don’t ’ave to say anythin’, Kathy love. I don’t want ter rush yer. It wouldn’t be fair to marry yer while this bleedin’ war’s goin’ on. Yer don’t want ter be a widow before you’re a wife.’

‘Billy!’ I went cold all over. ‘Don’t say that. Nothing is going to happen to you.’

‘Not if I can bleedin’ ’elp it!’ He grinned at me. ‘I’ve got too much ter come ’ome for. You are goin’ ter wait fer me, ain’t yer, Kathy?’

‘Don’t swear so much,’ I reproved with a little smile. ‘Da swears somethin’ terrible when he’s drunk and Gran hates it.’

‘I’ll try to remember,’ he said. ‘You will be my girl, Kathy – please?’

‘I’m not giving you my word yet, Billy. But if you promise not to get into any more fights I might go out with you again.’

‘We’ll go to the pictures tomorrow if yer like. There’s one of them Mack Sennett films on – the Keystone Kops, I think. Or we could go to a music hall if you’d rather. I’ve only got three days’ leave, Kathy, so we might as well make the most of it.’

‘Yes, all right,’ I agreed. ‘But remember, I’m not promising anythin’ yet.’

I thought about Billy when I was lying in bed that night. In the past I’d heard rumours about him getting into bad company, and I’d been very upset by the fight at the dance hall, but maybe he’d had to let off steam. All our men were under terrible strain out there, and Billy was no different from anyone else. I liked his smile and easy manner, and as I finally fell asleep I realized that I was looking forward to meeting him the next day.

I saw Billy twice more before he went back to his unit. We visited a music hall and saw Gertrude Lawrence and Jack Buchanan, joining in as the audience sang along with songs that had become so popular since the beginning of the war. On his last afternoon we went for a walk by the river and then had a drink in the pub.

It was a pleasant day despite the cool breeze and a lot of people were out walking about, making the most of the fine weather. The Sally Army was playing hymns outside the pub, and a group of children were marching after them banging on drums made out of old biscuit tins.

Billy looked at me anxiously as we lingered over our drinks. ‘You won’t go and marry anyone else, will yer?’

‘I’m not planning on it, Billy. I want to be a nurse when I can – to do something to help. I think of the war and about what’s happening out there all the time. All those lads getting killed and hurt.’

I had been reading the news about German submarines sinking ships, and the tremendous numbers of casualties at the Front, and it made me feel guilty for being safe at home when so many others were being killed.

Billy nodded, a serious expression on his face. ‘It’s bad, lass, real bad. We don’t talk about it much when we’re home on leave, but it’s a nightmare for the men. I’ve visited mates in the field hospitals out there, and those nurses are angels. I’d be proud for my girl to be one of them, so if that’s what you want to do I shan’t stand in yer way.’

Hearing the emotion in his voice I felt closer to him than ever before.

‘When will it be over, Billy? It’s more than three years since it started. Surely it can’t drag on much longer – can it?’

‘I wish I knew. Most of us who were out there at the start are sick of it – them what are left, that is. I’m one of the lucky ones. I’ve only ’ad a couple of scratches but I’ve seen some of me mates catch it. Us veterans ’ave to look out fer the young uns. Most of the new recruits they’re sendin’ us now are still wet behind the ears.’

‘It must be awful.’ I looked at him with sympathy, realizing for perhaps the first time how bad it must really be for the men in the trenches, seeing their friends get hurt. ‘You will take care, Billy? I shouldn’t like anythin’ to happen to you.’

‘I’m an old ’and at it now,’ he said and grinned. ‘It’s a matter of keeping your head down. Run away to fight another day and don’t be a hero – that’s what I say.’

‘Oh, Billy …’ I laughed. ‘I can’t see you runnin’ away from a fight.’

‘You’re never goin’ ter let me forget the other night are yer?’

‘Is your lip still sore?’ I asked and shook my head at him. Now that I’d had time to think about things I felt more pleased than angry that Billy had stuck up for me. I didn’t approve of fighting, of course, but it was nice that he’d cared so much.

‘Nah. It were just a little cut. I could kiss yer – if yer like?’

‘We’ll see. I think you’d better walk me home now or you’ll be late for your train – and Da will be back for his tea soon.’

So far my luck had held and my father hadn’t questioned me about my going out with Billy Ryan. I wasn’t sure that he knew. Even if he’d noticed I wasn’t around, he’d probably just assumed I was out with friends.

Billy finished his drink and stood, holding out his hand to me. I took it and we left the pub together, strolling through the lanes, which looked brighter than usual in the warm sunshine. In the distance we could hear the rattle of the trams and a hooter from one of the ships blasting off somewhere on the river. I’d heard that morning that an American ship had made its way here safely, bringing much-needed supplies to a country that was gradually running short of almost everything.

When we reached my doorstep, Billy lingered uncertainly. He was reluctant to leave and I knew he was waiting for the kiss I’d half promised him.

‘Oh, go on then,’ I said and moved towards him. ‘You can kiss me if you like.’

Billy smiled, reached out and drew me close to him. His kiss this time was much deeper and lasted longer than the first. I felt him shudder as he at last released me and I was trembling too. I gazed up at him wondering what emotion had made me feel so shivery inside.

‘You felt somethin’ too, didn’t yer, lass?’ Billy asked, looking down into my eyes. ‘I love yer, Kathy. I ’ave fer years. Wait fer me because I don’t think I could bear it out there if I thought yer were kissin’ another bloke.’ His tone and expression were so sincere that I was moved.

‘I like you a lot, Billy,’ I whispered feeling breathless. ‘I can’t promise that I’ll marry you, but I’ll think about you – and I don’t often go out with blokes. You’re the first I’ve let kiss me.’

‘Will yer write to me, Kathy? Ma will tell yer where if yer ask.’

‘I might now and then,’ I said. ‘Take care of yourself, Billy. We’ll see how we feel next time you come home.’

‘Fair enough,’ he said and that cocky grin spread across his face. ‘You’re my girl, Kathy Cole – whether you know it or not – and I’ll be claiming you when I get back.’

I smiled, but didn’t answer him, and I lingered on the doorstep to watch as he strolled down the lane. Billy’s kiss had certainly shaken me, but I still wasn’t ready to give him an answer.

I waved as Billy turned to look at me from the corner of the lane, and then I went into the house. I was smiling to myself, about to go upstairs when a yell of rage startled me and my father shot out of the kitchen and grabbed my arm.

‘You sly slut!’ he growled at me, his fingers digging deep into the flesh of my upper arm. ‘So that’s what you’ve been up ter behind me back!’

‘Leave off, Da, you’re hurtin’ me,’ I cried and pulled back from him. ‘What’s the matter with you? I’ve only been out for a drink with a friend.’

‘You’ve been out three times with that bleedin’ Billy Ryan,’ he muttered, his face puce with temper. ‘And don’t lie to me, girl, because you were seen by one of me mates.’

‘Billy is all right,’ I said rubbing at my arm where he’d hurt me. ‘We went out a few times because he was on leave – but we didn’t do anythin’ wrong. Billy respects me. He wants to marry me.’

‘I ’eard about the fight down the Pally,’ Da shouted, his face working furiously. ‘Makin’ a show of ’imself and you with ’im. No daughter of mine is goin’ around with a bloke like that.’

‘Billy was defending my honour,’ I said. ‘Someone tried to maul me and called me names – said I was like my mother.’ I looked at him defiantly. ‘Besides, you’re always getting into a brawl when you’ve been drinking. They threw you out of the Feathers last week and told you not to go back.’

Da raised his hand and struck me a heavy blow across the face, catching my lip. I gave a cry and jerked back as I tasted blood, gazing at him in horror. He had given me a clip of the ear in passing a few times when I was a child, but he’d never hit me like that before.

‘You shouldn’t have done that,’ I said. ‘You had no right to hit me like that.’ I felt like crying but I was determined not to let him see me weep.

‘That will teach you to cheek me,’ he muttered a sullen look in his eyes. ‘Your mother was a cheat and a whore – and I’ll kill yer afore I let you go the same way. You mind what I say, Kathy. See that Billy Ryan again and you’ll be sorry.’

He pushed past me and went out of the front door, slamming it behind him. For a moment I stood staring after him feeling shocked and numb. His rages and tempers had never really frightened me before, but now I wasn’t sure what he might do next.

Two

I tossed restlessly through most of that night, sleeping hardly at all. My face hurt where my father had hit me, but it was my pride and my sense of justice that had been hurt the most. I knew I had to change things, because I wasn’t going to let myself be beaten and used like so many of the women I knew. By the morning I had made up my mind.

‘It’s a bit desperate, Kathy,’ Gran said as I finished telling her my thoughts after breakfast. She was sitting by the fire, warming her hands round a mug of scalding hot tea, her expression anxious. ‘Ernie will come round in time. There’s no need for yer to go rushing off like this because of a quarrel. Besides, didn’t yer tell me yer had to be eighteen to enrol in the VADs? You’re not old enough until your next birthday – and that’s months away.’

‘He hit me, Gran.’ My face bore a purple bruise to prove it and I’d lain awake all night thinking about what my life would be like if I continued to go on as before. ‘If I stay here he might do it again. I’ve seen women in the lanes that get beaten regularly on a Saturday night, and I’m never going to let a man do that to me. I look old enough to pass for eighteen, you know I do – and if they want proof I’ll tell them we’ve lost my certificate. Lots of people I know would have difficulty proving their exact age.’

Gran acknowledged the truth of my words. In an area like ours some people didn’t even bother to register the birth of a child. The narrow lanes around Dawson’s Brewery had been almost a slum for years, though they were a much nicer place to live now due to the influence of Joe Robinson. Not content with improving the properties he owned, he had campaigned for the old warehouses that had harboured rats and vagrants to be pulled down. There was a stretch of grass in their place by the river now and the kids played there after school. Most of the houses in the lanes had running water and inside lavatories too.

‘I’ve never known exactly how old I am,’ Gran said, looking at me sadly as she leaned forward to poke up the fire. I’d been up early to black lead the grate and scrub the stone floor, which was covered with several peg rugs Gran had made from scraps of material. ‘I’ll miss yer if you go, Kathy – but maybe it’s for the best. Ernie’s temper gets worse all the time. If he doesn’t watch out Mr Dawson will get rid of him altogether, and then where will we be?’

‘He only keeps him on because he thinks he was to blame for the accident. At least that’s what Da says.’

‘That’s daft talk. Ernie has only himself to blame. He was drunk and he didn’t watch what he was doing with that load. It was his own fault it slipped and caught him, breaking his leg. The break never healed properly, that’s the pity of it.’ Gran sighed and looked at me. ‘When are you goin’?’

‘It might as well be today,’ I said and immediately felt guilty as I saw her expression of shock. ‘That’s if you’re feeling well enough to manage? I could stay a few days longer if you need me?’

She shook her head. ‘I’m better, Kathy. I shall miss yer, girl, but I won’t stand in your way if it’s what yer want – and maybe it’s for the best. I should think them hospital folk will be glad of a bit of ’elp. They need all the nurses they can get from what I ’ear of things.’

‘That’s how I feel,’ I said and kissed her cheek. ‘I know I shan’t be much use for a start, but I’m willing to do whatever they want and I don’t mind hard work.’

‘There will be ’ell to pay when Ernie knows you’ve gone, but never mind that, Kathy. I’ll give ’im a piece of me mind fer what he done to you.’

‘Don’t upset yourself over it, Gran.’ I touched the bruise gingerly with one finger. ‘It doesn’t hurt so much now and it will soon go.’

I felt guilty as I looked at her sitting there in her chair by the kitchen range, the fire blazing and putting out so much heat it was almost unbearable on a warm day like today unless you kept the yard door open. The fire and tiny oven beside it was Gran’s only method of cooking and there was usually a pot bubbling away on the top all day.

She was much better again now, but she wasn’t a young woman and I knew she would miss my help around the house. I didn’t like deserting her, yet I knew I had to get away for a while. For years I’d been aware that there was some mystery surrounding my mother, and my father’s harsh remarks about her had hurt me as much as the blow to my face. He’d seemed to hate her and, for a moment as he’d looked at me, I’d felt he hated me too.

It was hurtful to have my mother’s shame thrown at me like that, to feel that everyone was expecting me to behave in the same way, and I wanted to go right away from the lanes. Somewhere I wasn’t known. Somewhere I could be myself and hold my head up high.

There was another life away from the lanes, and this was my opportunity to find it, to make something of myself. I knew that if I didn’t take my chance now, I never would.

‘So you want to be a nurse, Miss Cole?’ The rather severe-looking woman behind the desk stared at me in what could only be described as a disapproving manner. ‘And what makes you imagine you have the qualifications for such an important task?’

I had waited several days to get this interview and I was feeling anxious as she glanced down at my application again. If she turned me down I didn’t know what I was going to do.

‘I know I’ve got a lot to learn, miss,’ I replied, meeting her forbidding gaze as steadily as I could. ‘But I’m a quick learner and I don’t mind how hard I work.’

‘Are you indeed?’ She drummed her fingers on the top of the battered-looking desk. ‘Well, we shall see. You have already been accepted into the VADs, but it is up to me whether I recommend you for the nursing branch or something else.’ She glanced at the papers in front of her. ‘You give your age as eighteen last birthday – you are a very young eighteen, Miss Cole.’

‘Am I?’ She waited for me to elaborate but I didn’t, lying wasn’t my strong point. I had a feeling this woman would know if I tried. ‘I’ll work really hard, miss.’

She continued to look at me thoughtfully for some minutes.

‘Yes, I think perhaps you will.’ She nodded as though making up her mind. ‘Very well, I’m going to put you forward. You will be sent to a hospital just outside London where they have a shortage of staff at present, and more patients than they can cope with, I’m afraid. It’s under the authority of the Military and the patients are all wounded personnel from one of the Armed Forces. You understand that at first you will be doing all the menial jobs the trained nurses just don’t have time for?’

‘Yes, miss. All I want to do is help – whatever it is.’

‘Then I shall not deny you the chance to serve, Miss Cole. Goodness knows, we need enthusiastic young women badly enough.’ She stamped a paper and handed it to me. ‘Take this to the desk on your way out. You will be provided with your ticket and all the necessary paperwork. You will be required to report to the duty officer on Monday morning without fail.’

‘Thank you.’ I took the paper she gave me gratefully, giving her a smile of thanks. ‘Thank you so much for passing me.’

‘Don’t let me down, Miss Cole.’ She gave me a wintry smile. ‘And I should let your birth certificate remain lost if I were you.’

The look in her eyes told me she had not been convinced that I was eighteen, but circumstances were such that she was willing to accept almost anyone she felt could be trusted to work and behave decently.

It wasn’t surprising with the way things had been going for the past eighteen months or more. The numbers of casualties, both dead and wounded, had been rising steadily as the fighting intensified and the hospitals were stretched to breaking point.

I had no illusions as I joined the queue at the recruitment agency’s reception desk. There was nothing glamorous about the job I had taken on. I was more likely to find myself emptying and scrubbing endless bedpans than smoothing the brow of a brave soldier, but at least I would feel needed and wanted. It was a chance for me, a chance to get away from the lanes and the past.

The memory of that quarrel with my father was still hurtful, but I’d made up my mind to put it behind me and look to the future. It was going to take years of hard work, but one day I would be able to call myself a nurse. I wanted to make something of myself.

‘Have you been accepted for nursing training too?’

I turned as the girl spoke behind me. She was several inches shorter than me, not much more than five foot five or six at most, whereas I was nearer five foot eight, but as I looked down into blue eyes that sparkled with fun I liked her immediately. She was pretty, had soft fair hair that curled about her face appealingly, and she was clearly very excited.

‘Yes – it was touch and go for a while, though; Miss Martin thought I might not be up to the work, but she accepted me in the end. I’ve been passed to train as a nurse, though I don’t suppose I’ll do much of that for a while.’

‘No – but it will be worthwhile in the end,’ she replied. ‘Miss Martin was a bit of an old battleaxe, wasn’t she? At first she said I would never stand up to the work because I’m too delicate. I told her I can eat and work like a horse, and that if she didn’t pass me I’d give a false name and try again until I did get someone to pass me. That made her stare, I can tell you.’ A giggle escaped her. ‘Mind you, I don’t suppose she had much choice really. They need girls so badly and they get an awful lot who fall by the wayside – find they can’t stand the hours or the work – or simply collapse under the strain. That’s what my cousin says anyway, and she has been in the Service from day one.’ She held her hand out. ‘I’m Alice Bowyer by the way. Ally for short.’

‘Kathy Cole.’ I shook her hand. ‘I’m being sent to a hospital just outside London – Military-controlled, she said.’

‘Me too,’ Ally agreed. ‘They’re short of staff there. Joan says they get most of the worst cases – badly burned or crippled by loss of limbs, long-term patients, I think. They’ve usually been in other hospitals for some weeks or even months, poor devils. Joan says that some of them will never be fit to go home.’

‘That’s such a shame. My friend was telling me it’s much worse out there than most of us know. The papers don’t tell us the half of it, according to Billy.’

‘Probably wouldn’t dare.’ She gave me a little push forward. ‘It’s your turn next. Will you wait for me? We can go for a cup of tea or something.’

‘Oh yes, I should like that. We shall be able to travel together, I expect.’

Ally nodded and gave me another push. The woman behind the counter took my paper and gave me a sheaf of leaflets with my instructions and information, and a small brown packet containing a ticket for the bus.

‘You’ll be one of fifteen personnel catching the bus,’ she told me. ‘Be there on time or you’ll be left behind. They don’t wait for stragglers. Miss it and you’ll have to make your own way.’

I thanked her and moved aside while Ally was given identical instructions. She grimaced as she joined me.

‘Anyone would think we were school children,’ she muttered. ‘I don’t know why they couldn’t give us the money and let us get there ourselves.’

‘We might take their money and run. Besides, it is a Military hospital and they probably want to control things their way – make sure we’re not spies or something. We might be German soldiers dressed up as girls …’

Ally laughed. ‘Daft! I thought you looked my sort. Where shall we go for a chat? I don’t know this part of London too well – I’m from the other side of the river, down Finsbury way. My father has a business there and we live near the shop. Let’s get something to eat, shall we? I’m starving.’

‘There’s a little teashop I’ve been using just up the road. It’s not bad and they make everything themselves.’

‘Do you live near here?’ She looked at me curiously.

‘I’ve got a room in the next street. It’s temporary – just until we go.’ I hesitated; then: ‘I had a row with my father and walked out last week.’

‘Oh, poor you,’ Ally said and linked her arm through mine. ‘My parents have been really good to me. They were expecting me to work in the shop – Dad owns a grocery business – but I told them I thought it was important to give something back to the men who were giving so much for us and they agreed.’