Полная версия

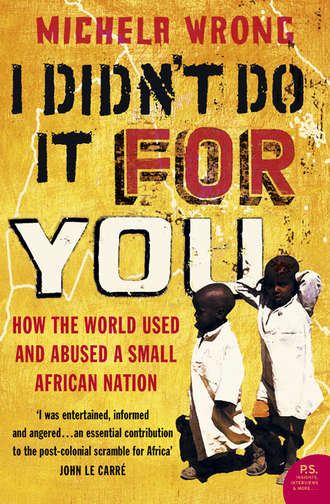

I Didn’t Do It For You: How the World Used and Abused a Small African Nation

Asmarinos today still refer to the city as âpiglo Romaâ and the centre of town as the âcombishtatoâ, bastardizations of the âpiccolo Romaâ Italy recreated on the Hamasien plateau and the campo cintato (âenclosed areaâ), ruled off-limits for Eritreans outside working hours âfor reasons of public order and hygieneâ. Eritrean merchants with premises on prime shopping streets were forced to surrender their leases to Italian entrepreneurs. Consigned to the public gallery at the cinema, Eritreans were barred from restaurants, bars and hotels and made to form separate queues at post offices and banks. Africans actually preferred to keep their distance, claimed the Italian Ministry for African Affairs in justification.33 Once, Eritreans and their white compatriots had greeted each other as âarkuâ (âfriendâ). In future, Fascism decreed, Italians would address Eritreans with the peremptory âattaâ and âattiâ (âyouâ), while the Eritrean was expected to use the respectful âgoitanaâ (âmasterâ) towards his white superior.

The new legislation enshrined the principle of separate education Martini had first embraced. And no matter how talented or well-heeled, an Eritrean could not stay longer than four years at his all-black school. Italy needed obedient translators, respectful artisans and disciplined ascaris, not trouble-making intellectuals. âThe Eritrean student should be able to speak our language moderately well; he should know the four arithmetical operations within normal limits; he should be a convinced propagandist of the principles of hygiene, and of history, he should know only the names of those who have made Italy great,â announced the colonyâs Director of Education.34 The subject of Italyâs Risorgimento was dropped entirely from the syllabus, for fear it might spark inappropriate ideas.

If the Fascist administrators disliked the notion of uppity natives, the prospect of an expanding âbreed of hybridsâ positively appalled.35 Young Italian soldiers, whose tendency to acquire female camp followers was noticed by reporters covering the conflict, marched into Abyssinia singing the popular hit âFacetta Neraâ (âLittle Black Faceâ), in which a black Abyssinian beauty is saved from slavery, taken to Rome by her lover and dressed in Fascismâs black shirt. A year later, the authorities were attempting to suppress the song as Italian newspapers warned that the Fascist Empire was in danger of becoming an âempire of mulattosâ.36 The new laws betrayed a vindictive determination to wipe out any vestige of affection, loyalty and love between the races. âConjugal relationsâ between Italians and colonial subjects were prohibited, marriages declared null and void. Italians who visited places reserved for ânativesâ were liable to imprisonment and it was ruled that an Italian parent could neither recognize, adopt or give his surname to a meticcio. With a stroke of the pen, Rome turned a generation of mixed-race Eritreans into bastards. âFiglio di Nâ was the mocking playground cry that greeted the mixed-race child, officially stripped of inheritance, citizenship and name: âson of Xâ.

Long before racial segregation was adopted as an official credo in South Africa, Eritrea had already tasted the delights of apartheid. In its day, it was the most racist regime in Africa. Eritreans no longer regarded their Italian administrators as âgood but stupidâ. Every Eritrean who lived through that era nurses in his memory a moment of humiliation he can today shake his head over with the bitter satisfaction that comes from knowing history has had the last laugh, a deep guffaw that comes from the belly. âWhen a white man walked along the street, you always followed a couple of steps behind, never alongside,â an old railwayman told me. âThe white man always walked alone.â âYou could be dying of thirst, but the cafés in the town centre would still refuse to serve you so much as a glass of water,â said another. A pastor remembered how, as a boy, he once made the mistake of crossing the road in front of an Italian policeman on a motorbike. âHe was quite a long way off, but as far as he was concerned I should have waited for him to pass. He caught up with me and slapped me round the face.â The pastor recalled an old Italian lawyer expostulating at his failure to step into the gutter as he passed. âHe said âHey, canât you see that a white man is coming?â,â he chuckled. âIt was his way of saying âGet off the pavementâ.â

For Italy, the conquest of Abyssinia and racial subjugation of Eritrea would prove Pyrrhic victories. Resistance by Haile Selassieâs followers meant much of the Abyssinian countryside remained unsafe, and the number of settlers never rose above the disappointing. The extravagantly-funded war plunged Rome into debt and while other European powers milked fortunes from their territories abroad, Italy, embarrassingly, never managed to make colonialism work for her financially. Pouring investment into both Eritrea and Ethiopia, her empire cost her more than she gained and the government was juggling ballooning budget deficits when the Second World War began. Thanks to the predictably easy victory in Abyssinia, Italians would enter that campaign with a dangerously unrealistic belief in their military might, a confidence which shattered at huge national cost. And while the European powers agreed temporarily to turn a blind eye to Mussoliniâs bullying, the Abyssinian campaign also marked the moment when Il Duceâs eventual destiny as Hitlerâs patsy began to take shape. Having thoroughly alienated the liberal democracies with his behaviour towards Abyssinia, Mussoliniâs natural place, increasingly, would seem alongside the Nazi leader.

The warâs most dramatic long-term outcome was to effectively kill off Italian colonialism. Crude and invasive, often loathed by Italian settlers whose presence in Eritrea predated Fascism, the racial legislation made daily life so ghastly for Eritreans that when history finally granted Italyâs African subjects an opportunity to decide their fate, they would turn and spit in the face of their former masters.

Looking back, many Eritrean intellectuals view the 1930s as the period in which the characteristics now regarded as quintessentially Eritrean began to take recognizable form. Every country which experiences colonialism is defined by how it digests humiliation. In many African states, the experience corroded a communityâs sense of self-worth, dripping through the generations like acid. But in Eritreaâs disciplined, tightknit communities, sure in the knowledge of their ancient traditions and religious faith, subjugation ate into the soul in a different way. In the kebessa, families had always prided themselves on settling their disputes without recourse to outsiders. Nothing was considered more undignified than being seen to lose control, to let go. The brutality of the racial laws was met with tight-lipped self-restraint. Turning inwards, the Eritreans bottled up their emotions and waited to see what the future would bring. âWhatever sun rises in the morning is our sun, and whichever king sits on the throne is our king,â runs a Tigrinya proverb which summarizes the bittersweet philosophy of a people accustomed to having things done to them. Since there was no point standing up to a mightier adversary, silence seemed the only way of salvaging self-respect. âYou knew what the consequences would be if you openly revolted, so you were advised to bide your time, to be patient. That was the advice my father always gave me when I was growing up: âjust be patientâ,â says Dawit Mesfin, an Eritrean intellectual living in London.37 He calls this preternatural calm, the apparent passivity cultivated in that era, âquietismâ. Like all superficial passivity, it was a lid on a pressure cooker, clamped over a storm of hurt pride and a longing for retribution.

CHAPTER 4 This Horrible Escarpment

âIt was contrary to every book that had ever been written, but it came off.â

Lieutenant-General Sir William Platt

If you drive two hours north-west of Asmara, on what was once Mussoliniâs Imperial Way, you eventually reach the town of Keren. The road takes you through eucalyptus groves, whose leaves, in the early morning, give off a heady medicinal perfume, before crossing a plateau of almost unimaginable bleakness. When it came to power in 1993, Eritreaâs new government launched an ambitious reforestation campaign and brave green saplings, their bark protected from nibbling goats by little iron wigwams, have been planted at neatly-spaced intervals along the way. But it will be decades before their handkerchiefs of shade make any impression on this glaring, denuded landscape. Much of the Hamasien highlands looks as though it was scooped up at a quarry and deposited from the tailend of a dumper-truck. With so little standing in its path, the wind is free to harry the cappuccino-coloured dust, so soft it could have been poured from a ladyâs powder compact, so fine a trailing fingertip registers no contact at all. Donkeys stand motionless in the middle of the road, as though stunned into imbecility by the heat and sheer unfairness of being expected to graze off an expanse of rubble.

Keren itself is a bustling crossroads of a town, a natural meeting point for Eritreaâs various tribes. White-robed nomads bring their animals to the weekly livestock market, a moaning, bleating, piebald medley of camels, sheep and goats. City dwellers make weekend jaunts to a Holy Shrine hidden in the womb of an ancient baobab and stroll along the colonnaded street where silversmiths crouch over bracelets and rings. But Keren only makes historical sense if you keep going, through the centre and out the other side. On the edge of town, by the side of the road that points towards the border with Sudan, lies a British cemetery from the Second World War. Jump over the low wall â visitors here are too occasional for anyone to man the gates permanently â and you can pace the rows of neat white British graves, each with its own crinkly bush of red geranium. The birthday-card triteness of the mottoes carved into the stones betrays a terrible anguish for young lives abruptly ended. âHe gave his life, forget him never, for in giving he lives for ever,â plead the relatives of 22-year-old W Hollings, who served with the West Yorkshire Regiment. âWith many sad regrets, we shall remember when the rest of the world forgets,â promises the family of PFC Mapes, 26. âIn memoryâs garden, we meet every day,â is the only consolation the mother of AV Simmons, just 18 when his life came to a sudden stop, can offer herself.

Further on, by the wayside, a grieving Madonna inclines her head in an expression of infinite tenderness. Her location is not accidental. A moment later, the road plunges, weaving and winding its tortured way through a ragged gash in the mountains which the British, mangling the local name, dubbed Dongolaas Gorge. Cliffs of bulbous brown rock crowd in on all sides, blocking out the sun, while the sheer slopes below are scattered with the rusting debris of vehicles that missed the curves. There is something oppressive about this pass, and it is a relief to emerge finally in the valley, a scrubby floodplain so dry it seems impossible water should ever run across these yellow sands. It is only when you hit the bottom and look back to where you came, that Kerenâs geography suddenly becomes clear. Between you and the town a knobbly range of barren peaks now stretches, a giant amphitheatre coddling Keren in its lap. With Dongolaas Gorge offering the only easy access route across this rock wall, Keren is one of the most formidable fortresses ever thrown up by nature.

This was the sight that met a force of around 30,000 British troops as it chased Italyâs retreating army from Kassala, on the Sudanese border, east across Eritrea. It was February 2, 1941 and the first dents were being knocked into what had until then seemed like an unstoppable Nazi and Fascist war machine. In the preceding two years, Hitler had swallowed up Czechoslovakia and Poland, invaded Norway and Denmark, toppled the French government and forced the humiliating evacuation of British forces from continental Europe. Hanging on to the German dictatorâs coat-tails, Mussolini had invaded Albania and Greece and used his colonies in north and east Africa to attack Egypt and eject the British from Somaliland. Afraid of losing control of the vital supply route through the Suez Canal to the Indian Ocean, Britain was hitting back. It had trounced Italian forces in Libyan Cyrenaica and was now sending three separate forces â one bearing with it the deposed Haile Selassie â in a vast pincer movement aimed at squeezing the life out of the marooned Italian administration in the Horn. Before the Red Sea could be made safe for Allied shipping, both Asmara and Massawa had to be captured. But between the advancing British forces and their target lay Keren.

No one remembers the battle of Keren now, except the men who fought there. Perhaps that is only to be expected. The Normandy landings were staged on beaches within reach of modern European holidaymakers, the Blitz left permanent scars on the map of London, every time Berliners gaze at their cityâs skyline, they are reminded of the devastation of Allied bombing. Keren took place in a country whose name was unfamiliar even to the soldiers dispatched there to fight, in a part of the world so alien as to be virtually unimaginable to those back home, against an enemy regarded as a joke. El Alamein and Tobruk were to be the African campaigns of the Second World War remembered by British audiences, not Keren. Even Eritreans, who live amongst memorials and cemeteries spawned by the battle, are distinctly fuzzy about the details, too obsessed with their own still raw military history to show much interest in an episode logged in the general category of âneo-colonialist adventuresâ.

Yet it was a linchpin episode, on which turned a long sequence of events stretching to eventual Allied victory. The BBCâs decision to send its star reporter Richard Dimbleby to cover the battle shows it recognized that fact. But as far as the BBC was concerned, Dimbleby was covering an early bout in a mighty strategic contest, not a liberation campaign. Not for the first time, Eritrea would play unwitting host to a battle in which its citizens would be slaughtered, yet their own aspirations remained almost immaterial, of interest purely for their passing propaganda potential. The battle of Keren might have been fought on Eritrean soil, but it was plotted, planned and ultimately capitalized on in the capitals of Axis and Allied powers.

It was to prove a grinding, infinitely testing campaign in which victory against the Italians, viewed until then with amused condescension, never looked assured. âIt was a dingdong battle, a soldiersâ battle, fought against an enemy infinitely superior in numbers, on ground of his own choosing,â General William Platt, head of the armed forces in Sudan and mastermind behind the Eritrean campaign, later said. âWe got down very nearly to bedrock, very nearly.â1 Those who took part and went on to fight in the deserts of North Africa, the streets of European cities and the jungles of Burma were to recall the fighting at Keren as the most dreadful they ever experienced. âPhysically, by World War Two standards, it was sheer hell,â remembered Major John Searight, of the Royal Fusiliers, in a letter written after the war. âNOTHING I met in nine months as a company commander in NW Europe compared with it.â2

It is interesting to log the process by which the mind gives form and shape to landscape. Colonial explorers in Africa had a knack for it, baptizing waterfalls and lakes whose existence had been known to locals for centuries after childhood sweethearts and royal patrons. When the British forces arrived on the Keren floodplain they looked at the scenery with the outsiderâs lazy eye. The soldiers, recruited not only from Britain but from India, Sudan and Palestine â these were the days of the British empire, after all â saw a craggy range of mountains, rising to 7,000 ft, pierced by an occasional curious nipple of rock. Foothills formed rucks in a ribbon of brown land that stretched across the horizon. From a distance, what little vegetation there was â sprays of candelabra cactus, stunted thorn bushes here and there â resembled a light dusting of pepper sprinkled by a giant hand. To the far east crouched a curious promontory resembling a squatting cat, to the far west rose a peak like a ripped-out molar.

Fear changes oneâs perspective, lending what was of purely abstract interest a sudden urgent relevance. By the time the men had moved on, 53 days later, every inch of the terrain had acquired a dreadful, unwanted intimacy, more familiar to them than the soft folds of their Yorkshire valleys or the alleyways

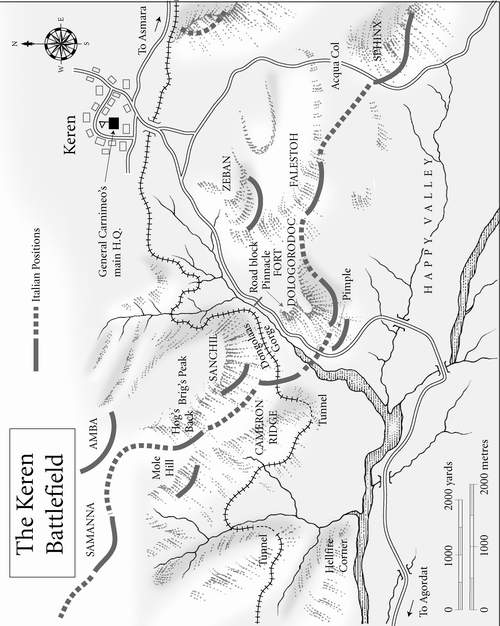

of their villages in the Punjab. Peaks and hillocks had been captured and lost, recaptured only to be surrendered again, as the front line juddered forwards and backwards. Each feature of the land had acquired its own distinct, tantalizing identity in the bloody baptisms that tracked the battleâs progress. Hellfire Corner, they called the point at which British troops were forced out of the shelter of the hills, exposing themselves to withering enemy fire. Above the horribly exposed plain, dubbed âHappy Valleyâ with the squaddieâs traditional irony, towered razor-sharp Mount Sanchil. The highest peak, it ran north-west, stretching into Brigâs Peak â christened after the 11th Brigade sent to conquer it â Hogâs Back and Mole Hill. At Sanchilâs base, overlooking the mouth of Dongolaas Gorge, reared the bluff that would be named Cameron Ridge, after the Cameron Highlanders who managed to scrape a vital first position there. Across the pass, above the foothills called the Pimple and the Pinnacle, rose Fort Dologorodoc, a cluster of trenches and cement parapets enjoying panoramic views. The cat-like formation became, with a certain inevitability, the Sphinx.

The Italians had never meant to make a stand at Keren. General Luigi Frusci, governor of Eritrea, had originally planned to dig in further up the road to Asmara. Since pulling out of Kassala in January, the Italians had been consistently on the defensive, holding up the British advance when the terrain gave them the upper hand, but always pulling out before losses rose. The British soldiers had almost been caught off-guard by an ambush at a place called Keru, where an Italian officer on a white horse had led a troop of Eritrean horsemen in a wild gallop straight into the mouths of the British guns.3 Taken by surprise by what must have been one of the last cavalry charges of the 20th century, British troops had recovered just in time, tipping their cannon so that they pointed into the ground in front of the horsesâ hooves. âIt was suicide, really, but it was gallantry one wouldnât expect of the Italians. They were totally destroyed,â remembered Colin Kerr, an intelligence officer with the Cameron Highlanders.4

As his troops withdrew ever further up the Imperial Way, Frusci belatedly realized the huge advantages Keren offered and ordered his men to stop and turn. There would have been no subsequent battle, had the British forces succeeded in keeping up their momentum. But the Italians had blown up a bridge behind them; and mined the river bed. By the time the obstacle had been cleared and the British convoy trundled into Happy Valley, the dull thud of explosions was audible ahead. General Orlando Lorenzini, the âLion of the Saharaâ to his men, was dynamiting the walls of Dongolaas Gorge, triggering a massive rock fall that closed off the pass. If Keren could be compared to a medieval fortress, the Italians had just rushed across the moat and pulled up the drawbridge.

Hoping to catch the Italians while they were still out of breath, British commanders ordered an immediate assault on Mount Sanchil. The Cameron Highlanders and Punjab Regiment stormed the slopes, capturing Cameron Ridge and Brigâs Peak, only to be forced off the latter by an Italian counterblast. âI saw a certain amount of the war after that, in various places, but the first 24 hours of Keren were about as unpleasant as any I saw anywhere,â recalled Kerr. âIt was incessant shelling and we were unable to reply to it because we were under observation.â The first attack ground to a halt as a sober understanding of the enormity of the task ahead dawned. The Italians, whose ranks were being swelled by reinforcements from the rear, were now dug in. They had set up machine guns and heavy mortars on all the loftiest points in the mountain range and designated them âlast man, last roundâ positions. There was to be no surrender, only death.

In contrast with what many civilians assume, military action does not always require extraordinary degrees of personal courage. Usually, the landscape offers so many possibilities for ambushes and outflanking movements, careful advance and sensible retreat, that a soldier can convince himself he stands a fair chance of surviving. Not so in Eritrea, where the campaign would essentially be fought along one road. On that road, Keren represented the head-on confrontation that brings with it the oppressive awareness of likely death. âIt was the first set-piece battle Iâd been near. The others were skirmishes where one could dodge out of the way. Here there was no avoiding it,â said one former artilleryman.5 Reconnaissance revealed that there was going to be no way of sidestepping this particular showdown: the mountain range stretched for 150 miles. âIt was a question,â recalled Platt, âof fighting this horrible escarpment somewhere or coming somewhat back. We could not live continuously under the escarpment.â6

When, in 2002, a British general took command of a UN peacekeeping force posted to Eritrea, he decided to use the battle of Keren as a training exercise for his under-employed troops. His aide-de-camp was ordered to dig out the 60-year-old military records, and groups of blue-capped UN officers were taken on tours of the battlefield to discuss how, facing the same logistical challenge but equipped with todayâs equipment, they would plan their attack.

I joined one of the tours, tagging along as the peacekeepers scrambled part way up Cameron Ridge to survey the terrain. None of us was carrying heavy loads, but we were soon stumbling and staggering, rasping for breath. The sand churned beneath our feet, making it hard to get a grip, rocks used for leverage had a nasty habit of rolling back onto you. It was only 10.00 in the morning, but it was already 41° C. The water in our plastic bottles had turned bathwater warm. Within a few minutes, I realized, to my embarrassment, that I was on the brink of fainting. Dots were dancing before my eyes. I couldnât seem to get enough oxygen into my lungs. The men in the group, I noticed with relief, looked no better: their faces had flushed an unbecoming gammon-pink.

âLook around you,â trumpeted the boisterous British general. âNo shelter anywhere from the sniper fire. Just imagine what it must have been like.â Our faces coated in a shiny slick of sweat, we gazed from the bare brown boulders on which the British had once crouched up to the unforgiving heights of Sanchil, where the Italians had sat waiting with their machine guns. âHorrid terrain to fight in,â muttered the general. âHorrid.â

Few of the soldiers mustering in Happy Valley had any real idea of the ordeal awaiting them. Their advance across Eritrea had gone swimmingly up until that point, with victory tumbling upon victory and few casualties suffered on the way. âWe were very confident. Morale was grand,â recalled Patrick Winchester, an artillery officer with the 4th Indian Division, just 21 at the time. âWeâd been up in the Western Desert, which was the first good thing to happen in the war. We thought âWeâll go and sort them out over there.ââ7