Полная версия

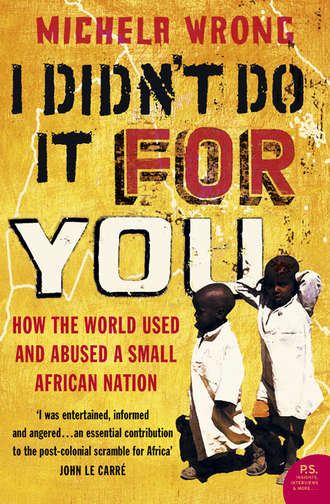

I Didn’t Do It For You: How the World Used and Abused a Small African Nation

Moving the capital from Massawa to cool Asmara, he set about his work with characteristic briskness. A series of decrees created a new civilian administration, placing the army firmly under its control. Strict limits were set to the number of civil servants employed in Eritrea, a move that slashed Romeâs expenditure. The worst soldiers and officers were simply expelled. âThese steps will cause a great deal of ill feeling, but I know I am doing my duty. Order, discipline, justice and thrift: without these the colony can neither be governed nor saved,â Martini pronounced.14 The colony was divided up into nine provinces, each with its own capital, and Martini established the building blocks of a modern society: an independent judiciary, a telegraph system and departments of finance, health and education.

The man who had calmly predicted the disappearance of Eritreaâs indigenous peoples quickly changed his tone. It was all very well airily discussing the elimination of local tribes as a passing visitor. Now that he was actually running Eritrea and could see for himself the damage â both political and commercial â done by military confrontation, Martini turned accommodating pacifier. Determined to shore up the Eritrean border, he became the perfect neighbour, putting an end to Romeâs long tradition of double-dealing. When rebel chiefs on the other side of the frontier challenged Menelikâs rule, Martini turned a deaf ear to their pleas for weapons. Instead of fantasizing, like so many Italian contemporaries, about avenging Adua, he cooperated with Menelikâs attempts to check the lawlessness on their mutual frontier, stabilizing the region in the process. As for emigration, Martini quickly realized how poorly judged the royal inquiry report had been. The colony was simply not ready for a flood of Italian labourers, who risked clashing with locals and would, in any case, be undercut by Eritreans willing to accept a fraction of what a European considered an honest wage. He scrapped legislation authorizing further land confiscation and pushed employers to narrow the huge differential between the wages paid Italians and Eritreans.

But while righting certain blatant injustices, Martini was never a soft touch. If Eritrea was to survive, the locals must be taught a lesson in the pitiless consistency of colonial law, the merest hint of insubordination ruthlessly crushed. Mutinous ascaris were shackled or whipped and the sweltering coastal jails filled with prisoners who often paid the ultimate price. âIâve never had a bloodthirsty reputation and I really donât deserve one,â Martini wrote, after refusing to pardon a condemned bandit. âBut here, without a death penalty, you cannot govern.â15 He was building a state, virtually from scratch, and often he felt as though he was doing the work single-handed. âThere is not a dog here with whom one can hold an intellectual discussion,â he complained in a letter to his daughter.16 It was a lonely, heady experience, bound to encourage delusions of grandeur. âAt times, unfortunately,â he confessed to his diary, âI feel it would not be too arrogant to say, adapting the words of Louis 14th, âI am the colonyâ.â17

The longer he stayed, the more convinced he became that the success of this monumental project hinged on one key element. He knew Eritrea had gold, fish stocks in abundance and river valleys capable of producing coffee and grain, cotton and sisal. But as long as a rickety mule track was the only way of scaling the mountains separating hinterland from sea, Eritrea would remain forever cut off from the African continent, its ports idle, its administration reliant on government subsidies. Only a railroad could unlock the riches of the plateau and â beyond it â the markets of Abyssinia and Sudan. It was the one explicit undertaking Martini had sought in exchange for his loyal service during his final conversation with King Umberto. âWithout a railway joining Massawa with the highlands, nothing good, lasting or productive will ever come from Eritrea,â he told the monarch. âRest assured,â the King had promised. âThe railway will be built.â18

The close of the 19th century was the golden era of African railways. Flinging their sleepers and coal-eating locomotives across savannah and jungle, the colonial powers sent a blunt message to the locals: progress was unstoppable. The railroad was both an instrument of war, depositing troops armed with machine guns within range of their spear-carrying enemies, and an instrument of commercial penetration, bringing the ivory, minerals and spices at the continentâs heart to market, opening the interior to land-hungry farmers and hopeful miners. Cecil Rhodes dreamt of one that would run from Cape to Cairo, the explorer Henry Stanley, nicknamed âBreaker of Rocksâ, was building one which would link Leopoldville to the sea, the British were braving man-eating lions to connect Uganda with the Swahili coast. Railways were the equivalent of todayâs national airlines â no African colony worth its salt could be without one.

Martini did not intend to be left out, although he knew Eritreaâs topography made this a uniquely demanding challenge. When Martini arrived, the Italian army had already laid 28 km of track to the town of Saati, carrying troops to fight Ras Alula. But the work had been carried out in such haste, it all needed to be redone. There were drawings to be sketched, sites visited, contracts put out to tender and strikes to be settled. It all fell to Martini, acutely aware that Italyâs colonial rivals were establishing their own trade routes into the interior, with France and Britain vying for control of a railway that would link Djibouti with Addis Ababa. âThe railway means peace, both inside and outside our borders, and huge savings on the budget,â he told his diary, time and again. Despite the Kingâs promise, winning the funding did not prove easy. Having sent Martini out with orders to cut spending, Rome did not take kindly to constant requests for money. He would waste months peppering the Foreign Ministry with telegrams, winning his bosses round to the railroadâs merits, only to see the government fall and a new set of ministers take office, who all had to be persuaded afresh. The railway, fretted Martini, âwould be the only really effective remedy to many â perhaps all â of the colonyâs ills. But in Rome they do not want to know.â19

He assembled a small army of 1,100 Eritrean labourers and 200 Italian overseers for the backbreaking and dangerous work, hacking and blasting through the rock, building stations and water-storage vaults as the railroad inched forwards. Struggling to master the technical minutiae of rail engineering, Martini found himself acting as peacemaker between irate private contractors and his abrasive head of works, Francesco Schupfer, a stickler for detail capable of forcing a company caught using sub-standard materials to knock down a stretch of earthworks and start again. âPerhaps he is too rough, but he is a gentleman,â Martini pondered, intervening yet again to smooth ruffled feathers. âHe is hated by everyone, but very dear to me.â20 When Britain raised the possibility of connecting Sudanâs rail network to the Eritrean line â a move that would have turned Massawa into eastern Sudanâs conduit to the sea â Martini was almost beside himself with excitement. âThis is a matter of life and death, either the railway reaches as far as Sabderat or we must leave Eritrea,â he pronounced.21 Just when his plans looked set in concrete, Rome began wondering â in a reflection of the changing technological times â whether it might not be better off investing in a highway to Gonder and Addis Ababa instead.

Despite all the telegrams and discussions, the stops and starts, the track slowly edged its way up to Asmara. By 1904, the crews had reached Ghinda, by 1911, four years after Martini had returned to Italy, it had reached Asmara. The final heave up the mountain proved the trickiest. Even today, old men living in Shegriny (âthe difficult placeâ), remember the dispute that lent their hamlet its name, as a father-and-son engineering team squabbled over the best route to take, each retiring to sulk in his tent before the precipitous route along âDevilâs Gateâ â little more than a narrow cliff ledge looking out over nothingness â was finally agreed.

The single most expensive public project undertaken by the Italians in Eritrea, Martiniâs railway was emblematic of his rule. Its construction marked the time when Eritrea, exposed to Western influences and endowed with the infrastructure of a modern industrial state, started down a path that would lead its citizens further and further away from their neighbours in feudal Abyssinia. Yet, as far as Martini was concerned, this gathering sense of national identity was almost an accidental by-product. Like so many colonial Big Men, he was haunted by the need to tame the landscape, to carve his initials into Eritreaâs very rocks. Literally hammering the nuts and bolts of a nation into place, he was more interested in the mechanical structures taking shape than what was going on in the heads of his African subjects. This colony was being created for Italyâs sake and if much of what he did improved life for Eritreans, it was motivated by an understanding of what was in Romeâs long-term interests, not altruism. No one could accuse Martini of remaining aloof â he toured constantly, setting up his marquee under the trees and receiving subjects whose customs he recorded in his diary. He knew the ways of the lowland Kunama and the nomadic rhythms of the Rashaida. But these were more the contacts of a deity with his worshippers than a parliamentarian with his constituents. This was the interest a lepidopterist shows in his butterfly collection â cool, distant and with a touch of deadly chloroform.

The approach is at its clearest when Martini writes about the two areas in which intimate contact between the races was possible: sex and education. Racial segregation had been practised in the colony since its inception. In Asmara, Eritreans were confined to the stinking warren of dwellings around the markets, while the Europeans, whose most prominent members donned white tie and tails to attend Martiniâs balls, lived in villas on the south side of the main street. Public transport was also segregated: Eritreans would have to wait another half-century to share the novel experience of using a busâs front door. But the races still mingled far more than the prudish Martini felt comfortable with. He disapproved of prostitutes, but was also repelled by the widespread phenomenon of madamismo, in which Italian officials took Eritrean women as concubines, setting up house together. The practice, he warned, raised a truly ghastly prospect. âA black man must not cuckold a white man. So a white man must not place himself in a position where he can be cuckolded by a native.â22 If the offspring of such unsavoury unions were abandoned, it would bring shame upon âthe dominant raceâ; if decently reared, it could ruin the Italian official concerned. Either outcome was to be deplored, so the entire situation was best avoided. It was an attempt at social engineering that enjoyed almost no success. By 1935, Asmaraâs 3,500 Italians had produced 1,000 meticci, evidence of a healthy level of interbreeding.23

But it is for his stance on education that Martini is chiefly resented by Eritreans today. The former education minister violently rejected â âNo, no and once again, noâ â any notion of mixed-race schooling. His justification was characteristically quixotic, the opposite of what one might expect from a man who had embraced the credo of racial superiority. âIn my view, the blacks are more quick-witted than us,â he remarked, noticing how swiftly Eritrean pupils picked up foreign languages.24 This posed a problem at school, he said, where âthe white manâs superiority, the basis of every colonial regime, is underminedâ. No mixed-race schooling meant there would be no opportunity for bright young Eritreans to form subversive views on their dim future masters. âLet us avoid making comparisons.â The natives must be kept in their place, taught only what they need to fulfil the subservient roles for which Rome thought them best suited. It was a variation of the philosophy Belgium would apply to the Congolese in the field of education: âPas dâélites, pas dâennemisâ (âNo elites, no enemiesâ).

In 1907, Martini asked to be recalled. He had pulled off a final diplomatic coup, travelling to Addis to pay his respects to an ailing Menelik II â âone of the ugliest men I have ever seen, but with a very sweet smileâ. It was a nightmarish journey during which the mules plunged up to their stomachs in mud and Martini, vain as ever, fussed constantly over the size of the ceremonial guard each provincial ruler sent to meet him.25 His work on the railway was not complete. It would never, in fact, be completed to his satisfaction, for Italyâs invasion of Ethiopia in the 1930s would interrupt construction of a final section intended to link the Eritrean line to Sudanâs network. But Romeâs procrastination had fatigued him. Being lord of all he surveyed had been enjoyable, but the small-mindedness of colonial life depressed him and he was fed up with army intrigues. As he prepared to embark aboard a P&O liner, with Eritreaâs notables â both black and white â mustered in Massawa to say goodbye, the man of letters was, for once, lost for words. âI feel such emotion that I have neither the strength nor ability to express it.â

His farewell message to the Eritrean people reveals just how far the anti-colonialist of yesteryear had travelled, how heady the role of Lord Jim, sustained over nearly a decade, had proved. It reads more like a prayer penned by an Old Testament patriarch ascending to his rightful place at Godâs side, than an Italian politician returning to his Tuscan constituency and, eventually, the top job at a newly-created Ministry for Colonies.

âPeople from the Mareb to the sea, hear me! His Majesty the King of Italy desired that I should come amongst you and govern in his name. And for ten years I listened and I judged, I rewarded and I punished, in the Kingâs name. And for ten years I travelled the lands of the Christian and the Moslem, the plains and the mountain, and I said âgo forth and tradeâ to the merchants and âgo forth and cultivateâ to the farmers, in the Kingâs name. And peace was with you, and the roads were opened to trade, and the harvests were safe in the fields. Hear me! His Majesty the King learnt that his will had been done, by the Grace of God, and has permitted me to return to my own country. I bid farewell to great and small, rich and poor. May your trade prosper and your lands remain fertile. May God give you peace!â26

With this portentous salutation, the Martini era came to a close.

He left behind a society transformed, but one â as far as its Eritrean majority was concerned â that held him in awe rather than affection. Today, when most Eritreans learn English at school, Martini has become little more than a name, his thoughts and achievements obscured by the barrier of language. Asmara holds not a single monument to this seminal figure. But older, Italian-speaking Eritreans remember, and their assessment of Martini is as ambivalent as the man himself. âHis legacy has been enormous, yet his aim was always to keep Eritrea in chains,â says Dr Aba Isaak, a local historian. âHe was a number one racist, but a superb statesman. I admire him, even while I regard him as my enemy.â27

When Martini left, there was no doubt in his mind that his government owed him thanks beyond measure. By his own immodest assessment, he had shored up a bankrupt enterprise and âsavedâ an entire colony from abandonment, transforming a military garrison into a modern nation-state. But Martini had also laid the groundwork â quite literally, in the case of the railway â for the sour years of Fascism, when the implicit racism of his generation of administrators was turned into explicit law, and a colonial regime that had seemed a necessary irritation began to feel to Eritreans like an intolerable burden.

In the years that followed, the colony would serve as little more than a supplier of cannon fodder for Italyâs campaign in Libya, sending its ascaris to seize Tripolitania and Cyrenaica from the Turks in 1911. Italyâs African pretensions were largely forgotten as the country was plunged into the horrors of the First World War. The Allied carve-up of foreign territories following that conflict left Italians bruised. Right-wingers who still quietly pined for an African empire felt their country had been promised a great deal while the fighting raged, only to be palmed off with very little by the Allies when the danger of German victory passed. It was an anger that played perfectly into the hands of the bully who was about to seize control of Italy.

As a youthful Socialist, Benito Mussolini had railed against liberals such as Martini for frittering away funds he felt would have been better spent tackling Italyâs underdeveloped south, actually going to prison for opposing Italyâs invasion of Libya. But once he assumed office in 1922 as prime minister, Mussoliniâs attitude to empire changed. Hardline Fascist commanders were dispatched to Libya and Somalia, where they ruthlessly crushed local resistance and expropriated the most fertile land. The extreme nationalism at Fascismâs core required a rallying cause and Mussolini was a great believer in the purifying power of battle. âTo remain healthy, a nation should wage war every 25 years,â he maintained. He was determined to prove to other European powers that Il Duce deserved a seat at the negotiating table. Nursing expansionist plans for Europe, he needed a quick war that could be decisively won, giving the public morale a boost before it faced more formidable challenges closer to home. Abyssinia, which many Italians continued to regard, in defiance of all logic, as rightfully theirs, seemed the perfect choice. France had Algeria, Britain had Kenya. It was only fair Italy should have her âplace in the sunâ.

As the official propaganda machine cranked into action, Italians were once again sold the idea of Abyssinia as an El Dorado of gold, platinum, oil and coal, a land ready to soak up Italian settlers â Mussolini put the number at a blatantly absurd 10 million. Once again, one of Africaâs oldest civilizations was portrayed as a land of barbarians, who needed to be âliberatedâ for their own good. Italian officials were not alone in nursing a vision of Abyssinia that could have sprung from the pages of Gulliverâs Travels. âThere human slavery still flourishes,â Time magazine told its readers in August 1926. âThere the most trifling jubilation provides an excuse for tearing out the entrails of a living cow, that they may be gorged raw by old and young.â Itching for a pretext to declare war on Ras Tafari, the former Abyssinian regent who had been crowned Emperor Haile Selassie in 1930, Mussolini finally seized on a clash between Italian and Abyssinian troops at an oasis in Wal Wal as a pretext. Retribution had been a long time coming, but the battle of Adua was about to be avenged.

For Eritrea, the obvious location for Italyâs logistical base, the forthcoming invasion meant boom times. Ca Custa Lon Ca Custa (âWhatever it costsâ) reads the slogan, written in Piedmontese dialect, carved into the cement of the ugly Fascist bridge which fords the river at Dogali. It epitomized Mussoliniâs entire approach to the war he launched in the autumn of 1935, ordering a mixed force of Italian soldiers and Eritrean ascaris to cross the Mareb river dividing Eritrea from Abyssinia. âThere will be no lack of money,â he had promised the general in charge of operations, Emilio de Bono, and the ensuing campaign would be characterized by massive over-supply.28 When de Bono asked for three divisions, Mussolini sent him 10, explaining: âFor the lack of a few thousand men, we lost the day at Adua. We shall never make that mistake. I am willing to commit a sin of excess but never a sin of deficiency.â29 Some 650,000 men, including tens of thousands of Blackshirt volunteers, were eventually sent to the region and with them went 2m tonnes of material, probably 10 times as much as was actually needed. Flooded with supplies â much of it would sit rotting on the Massawa quayside, only, eventually, to be dumped in the sea â Eritreaâs facilities suddenly looked in dire need of modernization.

A 50,000-strong workcrew was dispatched to do the necessary: widening Massawa port, building hangars, warehouses, barracks and a brand-new hospital. The road to Asmara was resurfaced, airports built, bridges constructed. Martiniâs heart would have thrilled with pride, as his beloved railway finally came into its own. Trains shuttled between Massawa and Asmara nearly 40 times a day, laden with supplies for the front. Even this was not considered sufficient, however, and, in 1936, work started on another miracle of engineering, the longest, highest freight-carrying cableway in the world. The 72-km ropeway erected by the Italian company of Ceretti and Tanfani, strung like a steel necklace across the mountain ranges, was as much about demonstrating the white manâs mastery over the landscape as meeting any practical need. It was exactly the kind of high-profile, macho project Mussolini loved.

Asmara blossomed. New offices and arsenals, car parks and laboratories sprang up, traffic queues for the first time formed on the cityâs streets. The most modern city in Africa boasted more traffic lights than Rome itself. Soon the simple one-storey houses of the 19th century were dwarfed by Modernist palazzi. In the space of three frenzied years, Italyâs avant-garde architects, presented with a nearly blank canvas and generous state sponsorship, created a new city. A mere five years before Mussoliniâs new Roman empire was to crumble into dust, Eritreaâs designers dug foundations and poured cement, never doubting, it seems, that this empire was destined to endure.

It was a short military campaign. By May 2, 1936, Italyâs tactic of bombing Abyssinian hospitals and its widespread use of mustard gas, which poisoned water sources and brought the skin out in leprous, festering blisters, had had the desired effect. With his army in tatters and Italian troops marching on Addis, Haile Selassie fled the country. He made one last poignant appeal for help before the League of Nations in Geneva, where, jeered by right-wing Italian journalists, he warned member states that their failure to stop Mussolini would destroy the principle of collective security that had been the organizationâs raison dâêtre. âInternational morality is at stake,â he said, âwhat answer am I to take back to my people?â30 European powers, who had already decided to take no more than token action, listened in silent embarrassment to this Cassandra-like warning. Riding a wave of popular rejoicing, Mussolini set about dividing Haile Selassieâs territory on ethnic lines. Abyssinia was swallowed up in Italian East Africa, a vast new Roman empire which embraced Eritrea and Somalia and covered 1.7 million sq km, stretching from the Indian Ocean to the borders of Kenya, Uganda and Sudan.

In Eritrea, this should have been a golden age, for white and black alike. But while the economy thrived, relations between Eritreans and Italians had never been worse. The new Italians, Eritreans quickly noticed, were different from the old. They came from the same modest backgrounds as their predecessors, but they seemed, like Il Duce himself, to feel a swaggering need to demonstrate constantly who was boss. There was little danger of these new arrivals, convinced of their Aryan superiority, becoming insabbiati: they despised the locals too thoroughly to mix. âEvery hour of the day, the native should view the Italian as his master, sure of himself and his future, with clear and defined objectives,â explained an Italian writer of the day.31 To that end, a raft of increasingly oppressive racial laws was introduced across Italian East Africa between 1936 and 1940. Part and parcel of the anti-Semitic legislation being adopted in mainland Italy, they aimed at keeping the black man firmly in his place.32