Полная версия

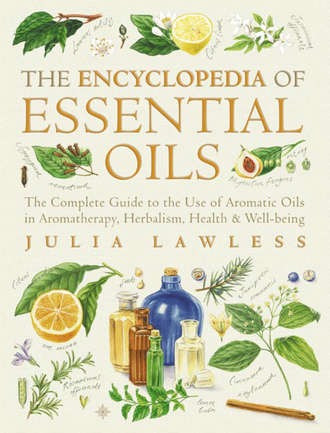

Encyclopedia of Essential Oils: The complete guide to the use of aromatic oils in aromatherapy, herbalism, health and well-being.

COPYRIGHT

HarperThorsons

An Imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 77–85 Fulham Palace Road, Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain in 1992 by Element Books Limited

This revised and updated edition published by HarperThorsons 2014

Botanical illustrations by Sarah Roche

© Julia Lawless 1992

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

While every effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright material reproduced herein and secure permissions, the publishers would like to apologise for any omissions and will be pleased to incorporate missing acknowledgements in any future edition of this book.

Julia Lawless asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

Source ISBN: 9780007145188

EPub Edition © SEPTEMBER 2014 ISBN: 9780007405213

Version: 2014-10-01

DEDICATION

To my mother, Kerttu

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Preface

How to Use This Book

Part I: An Introduction to Aromatics

1. Historical Roots

Natural Plant Origins

Ancient Civilizations

Treasures from the East

Alchemy

The Scientific Revolution

2. Aromatherapy and Herbalism

The Birth of Aromatherapy

Herbal Medicine

Therapeutic Guidelines

Safety Precautions

3. The Body-Actions and Applications

How Essential Oils Work

The Skin

The Circulation, Muscles and Joints

The Respiratory System

The Digestive System

The Genito-urinary and Endocrine Systems

The Immune System

The Nervous System

The Mind

4. How to use Essential Oils at Home

Massage

Skin Oils and Lotions

Hot and Cold Compresses

Hair Care

Flower Waters

Baths

Vaporization

Steam Inhalation

Douche

Neat Application

Internal Use

5. Creative Blending

Therapeutic and Aesthetic Properties

Correct Proportions

Synergies

Fragrant Harmony

Personal Perfumes

6. A Guide to Aromatic Materials

Habitat

Chemistry

Methods of Extraction

Natural versus ‘Nature Identical’

Part II: THE OILS

Ajowan

Allspice

Almond, Bitter

Ambrette Seed

Amyris

Angelica

Anise, Star

Aniseed

Arnica

Asafetida

Balsam, Canadian

Balsam, Copaiba

Balsam, Peru

Balsam, Tolu

Basil, Exotic

Basil, French

Bay, West Indian

Benzoin

Bergamot

Birch, Sweet

Birch, White

Boldo Leaf

Borneol

Boronia

Broom, Spanish

Buchu

Cabreuva

Cade

Cajeput

Calamintha

Calamus

Camphor

Cananga

Caraway

Cardamon

Carrot Seed

Cascarilla Bark

Cassia

Cassie

Cedarwood, Atlas

Cedarwood, Texas

Cedarwood, Virginian

Celery Seed

Chamomile, German

Chamomile, Maroc

Chamomile, Roman

Champaca

Chervil

Cinnamon

Citronella

Clove

Coriander

Costus

Cubebs

Cumin

Cypress

Deertongue

Dill

Dorado Azul

Elecampane

Elemi

Eucalyptus, Blue Gum

Eucalyptus, Broad-leaved Peppermint

Eucalyptus, Lemon-Scented

Fennel

Fenugreek

Fir Needle, Silver

Fragonia

Frangipani

Frankincense

Galangal

Galbanum

Gardenia

Garlic

Geranium

Ginger

Goldenrod

Grapefruit

Greenland Moss

Grindelia

Guaiacwood

Ho Wood

Hops

Horseradish

Hyacinth

Hyssop

Immortelle

Jaborandi

Jasmine

Juniper

Labdanum

Laurel

Lavandin

Lavender, Spike

Lavender, True

Lemon

Lemongrass

Lime

Linaloe

Linden

Litsea Cubeba

Lotus

Lovage

Mandarin

Manuka

Marigold

Marjoram, Sweet

Mastic

Melilotus

Melissa

Mimosa

Mint, Cornmint

Mint, Peppermint

Mint, Spearmint

Mugwort

Mustard

Myrrh

Myrtle

Narcissus

Neroli

Niaouli

Nutmeg

Oakmoss

Onion

Opopanax

Orange, Bitter

Orange, Sweet

Oregano, Common

Oregano, Spanish

Orris

Osmanthus

Palmarosa

Parsley

Patchouli

Pennyroyal

Pepper, Black

Petitgrain

Pine, Dwarf

Pine, Longleaf

Pine, Scotch

Plai

Ravensara

Ravintsara

Rose, Cabbage

Rose, Damask

Rosemary

Rosewood

Rue

Sage, Clary

Sage, Common

Sage, Spanish

Sandalwood

Santolina

Sassafras

Savine

Savory, Summer

Savory, Winter

Schinus Molle

Snakeroot

Spikenard

Spruce, Hemlock

Styrax, Levant

Tagetes

Tansy

Tarragon

Tea Tree

Thuja

Thyme, Common

Tonka

Tuberose

Turmeric

Turpentine

Valerian

Vanilla

Verbena, Lemon

Vetiver

Violet

Wintergreen

Wormseed

Wormwood

Yarrow

Ylang Ylang

References

Bibliography

Useful Addresses

General Glossary

Therapeutic Index

Botanical Classification

Botanical Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

About the Publisher

Woodcut from the title page of the Crete Herball, 1526

PREFACE

My own interest in essential oils and herbal remedies derives from the maternal side of my family who came from Finland, where home ‘simples’ retained popularity long after they had vanished from most parts of Britain. My Finnish grandmother knew a great deal about herbs and wild plants which she passed on to my mother, as she recalls:

Mama’s most important herb was parsley, which along with dill, marjoram, hops and others, were dried in bunches in the autumn, dangling at the ends of short lengths of cotton, all strung on a long length of thin rope stretching right across the kitchen stove. As scents are very evocative for remembering old things, I remember it so well – the strong and heady smell emanating from these herbs when they were hung up, and the stove was warm.

Later, as a biochemist, my mother became involved with the research of essential oils and plants, and helped inspire in me a fascination for herbs and the use of natural remedies. Without her early enthusiasm and guidance, I’m sure this book would never have been written.

In 1992 the first edition of this book was published in the UK. Since then it has been translated into many languages as well being released in several different formats, including an illustrated edition. Now, with this new 2014 edition, I am very glad to have the opportunity to update my original work. Apart from revising my original text, I have also included fifteen new oils, which have been chosen especially for their therapeutic potential: these include a few little-known essential oils.

In the twenty-year period since the original publication of The Encyclopedia of Essential Oils, the use of essential oils, together with the practice of aromatherapy in the West, has undergone a radical transformation. At the beginning of the 1990s, aromatherapy was still considered a fringe practice and the use of essential oils in the home was by no means widespread. However, as scientific trials and clinical research have continued to confirm the potentiality of essential oils, they have become increasingly respected within the medical arena. This has been accompanied by a steady increase of public interest in holistic therapies worldwide, and a sociological trend towards embracing all things ‘natural’ over the past two decades.

Nowadays, aromatherapy treatments are widely available, including in hospitals, while essential oils can be purchased on every high street. This change in attitude can only be of benefit, but it is worth considering that the commercialization of aromatherapy has brought its own dangers. Although essential oils are all wholly natural substances, they can be subject to adulteration, so it is important always to buy them from a reputable supplier (see here). It is also vital to check that any specific safety guidelines are followed with care at home. It is my hope that this new edition will bring fresh life to the multifaceted and multicultural study of essential oils and to the field of contemporary aromatherapy.

HOW TO USE THIS BOOK

The Encyclopedia of Essential Oils is divided into two parts:

Part I is a general introduction to aromatics, showing their changing role throughout history, from the ritual part they played in ancient civilizations, through medieval alchemy, to their modern-day applications in aromatherapy, herbalism and perfumery.

Part II is a systematic survey of over 160 essential oils shown in alphabetical order according to the common name of the plants from which they are derived. Detailed information on each oil includes its botanical origins, herbal/folk tradition, odour characteristics, principal constituents and safety data, as well as its home and commercial uses.

This book can be approached in several ways:

1. It can be employed as a concise reference guide to a wide range of aromatic plants and oils, in the same way as a traditional herbal.

2. It can be used a self-help manual, showing how to use aromatherapy oils at home for the treatment of common complaints and to promote well-being.

3. It can be read from cover to cover as a comprehensive textbook on essential oils, shown in all their different aspects.

1. When using the book as a reference guide to essential oils, the name of the plant or oil may be found in the Botanical Index at the back of the book, where it is listed under:

a) its common name: for example, frankincense;

b) its Latin or botanical term: Boswellia carteri;

c) its essential oil trade name: olibanum;

d) or by its folk names: gum thus.

Other varieties, such as Indian frankincense (Boswellia serrata), may be found in the Botanical Classification section under their common family name ‘Burseraceae’, along with related species such as elemi, linaloe, myrrh and opopanax. Less common essential oils, such as blackcurrant (which is used mainly by the food industry), do not appear in the main body of the book, but are included in the Botanical Classification section under their common family name, in this case ‘Grossulariaceae’.

2. When using the book as a self-help manual on aromatherapy, it is best to consult the Therapeutic Index at the end of the book, where common complaints are grouped according to different parts of the body:

Skin Care

Circulation, Muscles and Joints

Respiratory System

Digestive System

Genito-urinary and Endocrine Systems

Immune System

Nervous System

If for example, we have been working long hours at a desk and have developed a painful cramp in our neck, we should turn to the section on Circulation, Muscles and Joints where we find the heading ‘Muscular Cramp and Stiffness’. Of the essential oils which are listed, those shown in italics are generally considered to be the most useful and/or readily available, in this case allspice, lavender, marjoram, rosemary and black pepper. The choice of which oil to use depends on what is to hand, and on assessing the quality of each oil by consulting their entry in Part II of the book. Special attention should be paid to the safety data on each oil: both allspice and black pepper are known to be skin irritants if used in high concentration; rosemary and marjoram should be avoided during pregnancy; rosemary should not be used by epileptics at all. On the basis of our assessment, we may choose to use lavender, marjoram and a little black pepper which would make an excellent blend. Some of the principles behind blending oils can be found in Chapter 5, Creative Blending.

The various methods of application are indicated by the letters M, massage; C, compress; B, bath etc. Turn to Chapter 4, How to Use Essential Oils at Home, where you will find instructions on how to make up a massage oil or compress, and how many drops of oil to use in a bath. Further information on how essential oils work in specific cases can be found in Chapter 3, The Body – Actions and Applications.

3. Used as a comprehensive textbook, The Encyclopedia of Essential Oils provides a wealth of information about the essential oils themselves in all their various aspects, including their perfumery and flavouring applications. It shows the development of aromatics through history and the relationship between essential oils and other herbal products. It defines different kinds of aromatic materials and their methods of extraction, giving up-to-date areas of production. In addition, it includes information on their chemistry, pharmacology and safety levels. The ‘Actions’ ascribed to each plant refer either to the properties of the whole herb, or to parts of it, or to the essential oil. Difficult technical terms, mainly of a botanical or medical nature, are explained in the General Glossary at the end of the book.

However, since the therapeutic guidelines presented in the text are aimed primarily at the lay person without medical qualifications, the section dealing with the aromatherapy application of essential oils at home is limited to the treatment of common complaints only: Although there is a great deal of research being carried out at present into the potential uses of essential oils in the treatment of diseases such as cancer, AIDS and psychological disorders, these discussions fall beyond the scope of this book. References to the medical and folk use of particular plants in herbal medicine and their actions are intended to provide background information only, and are not intended as a guide for self-treatment.

1. HISTORICAL ROOTS

Natural Plant Origins

When we peel an orange, walk through a rose garden or rub a sprig of lavender between our fingers, we are all aware of the special scent of that plant. But what exactly is it that we can smell? Generally speaking, it is essential oils which give spices and herbs their specific scent and flavour, flowers and fruit their perfume. The essential oil in the orange peel is not difficult to identify; it is found in such profusion that it actually squirts out when we peel it. The minute droplets of oil which are contained in tiny pockets or glandular cells in the outer peel are very volatile, that is, they easily evaporate, infusing the air with their characteristic aroma.

A Herbalist’s Garden; Le Jardin de Santé, 1539

But not all plants contain essential or volatile oils in such profusion. The aromatic content in the flowers of the rose is so very small that it takes one ton of petals to produce 300g of rose oil. It is not fully understood why some plants contain essential oils and others not. It is clear that the aromatic quality of the oils plays a role in the attraction or repulsion of certain insects or animals. It has also been suggested that they play an important part in the transpiration and life processes of the plant itself, and as a protection against disease. They have been described as the ‘hormone’ or ‘life-blood’ of a plant, due to their highly concentrated and essential nature.

Aromatic oils can be found in all the various parts of a plant, including the seeds, bark, root, leaves, flowers, wood, balsam and resin. The bitter orange tree, for example, yields orange oil from the fruit peel, petitgrain from the leaves and twigs, and neroli oil from the orange blossoms. The clove tree produces different types of essential oil from its buds, stalks and leaves, whereas the Scotch pine yields distinct oils from its needles, wood and resin. The wide range of aromatic materials obtained from natural sources and the art of their extraction and use has developed slowly over the course of time, but its origins reach back to the very heart of the earliest civilizations.

Ancient Civilizations

Aromatic plants and oils have been used for thousands of years, as incense, perfumes and cosmetics and for their medical and culinary applications. Their ritual use constituted an integral part of the tradition in most early cultures, where their religious and therapeutic roles became inextricably intertwined. This type of practice is still in evidence: for example, in the East, sprigs of juniper are burnt in Tibetan temples as a form of purification; in the West, frankincense is used during the Roman Catholic mass.

In the ancient civilizations, perfumes were used as an expression of the animist and cosmic conceptions, responding above all to the exigencies of a cult … associated at first with theophanies and incantations, the perfumes made by fumigation, libation and ablution, grew directly out of the ritual, and became an element in the art of therapy.1

The Vedic literature of India dating from around 2000 BC, lists over 700 substances including cinnamon, spikenard, ginger, myrrh, coriander and sandalwood. But aromatics were considered to be more than just perfumes; in the Indo-Aryan tongue, ‘atar’ means smoke, wind, odour and essence, and the Rig Veda codifies their use for both liturgical and therapeutic purposes. The manner in which it is written reflects a spiritual and philosophical outlook, in which humanity is seen as a part of nature, and the handling of herbs as a sacred task: ‘Simples, you who have existed for so long, even before the Gods were born, I want to understand your seven hundred secrets! … Come, you wise plants, heal this patient for me’.2 Their understanding of plant lore developed into the traditional Indian or Ayurvedic system of medicine, which has enjoyed an unbroken transmission up to the present day.

The Chinese also have an ancient herbal tradition which accompanies the practice of acupuncture, the earliest records being in the Yellow Emperor’s Book of Internal Medicine dating from more than 2000 years BC. Among the remedies are several aromatics such as opium and ginger which, apart from their therapeutic applications, are known to have been utilized for religious purposes since the earliest times, as in the Li-ki and Tcheou-Li ceremonies. Borneo camphor is still used extensively in China today for ritual purposes. But perhaps the most famous and richest associations concerning the first aromatic materials are those surrounding the ancient Egyptian civilization. Papyrus manuscripts dating back to the reign of Khufu, around 2800 BC, record the use of many medicinal herbs, while another papyrus written about 2000 BC speaks of ‘fine oils and choice perfumes, and the incense of temples, whereby every god is gladdened’.3 Aromatic gums and oils such as cedar and myrrh were employed in the embalming process, the remains of which are still detectable thousands of years later, along with traces of scented unguents and oils such as styrax and frankincense contained in a number of ornate jars and cosmetic pots found in the tombs. The complete iconography covering the process of preparation for such oils, balsams and fermented liqueurs was preserved in stone inscriptions by the people of the Nile valley. The Egyptians were, in fact, experts of cosmetology and renowned for their herbal preparations and ointments. One such remedy was known as ‘kyphi’; a mixture of sixteen different ingredients which could be used as an incense, a perfume or taken internally as a medicine. It was said to be antiseptic, balsamic, soothing and an antidote to poison which, according to Plutarch, could lull one to sleep, allay anxieties and brighten dreams.