Полная версия

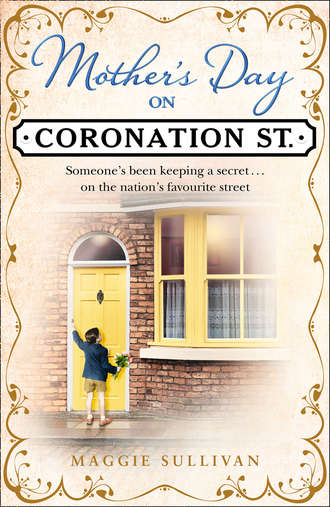

Mother’s Day on Coronation Street

‘At least it’s a clean job and it’s honest work,’ Annie said.

‘Well, Daddy certainly couldn’t have entertained getting a manual job like those dreadful men we passed on the way here. They looked so rough.’ Florence was trembling as she spoke. ‘Really low, working-class men they looked. They probably spend half their lives in a pub,’ she added contemptuously. ‘You must never forget, Annie, that regardless of what has happened to us we are not like the common people of the lower orders.’

‘At least whatever wages you get will put some food on the table,’ Annie said to her father who seemed to be preoccupied peering into cupboards.

He stood up. ‘As I see it, most of whatever pittance of a wage I earn will be going in rent. Imagine, we have to pay rent for this … this hovel.’

‘Don’t worry, Daddy,’ Annie said encouragingly. ‘I’ll go to work too. Just as soon as I can find a job.’

She thought that would please him, but instead of looking happy her father shook his head. ‘That’s wonderful. We are descendants of the line of the great Beaumonts of Clitheroe; we can trace our roots back to William the Conqueror and we’re used to having nothing but the best. We should be enjoying servants to make our lives comfortable as we get older and instead my only daughter is talking about going out to work.’

‘Not just me. Mummy, you will have to work too,’ Annie said, though she was not sure how that would be received.

Her father raised his eyebrows and Florence looked aghast. But Annie sounded determined. ‘Don’t you agree, Mummy? I suggest you make it known among the neighbours that you’re an extremely able needlewoman. It would help enormously if you could begin to take in some sewing.’

Florence looked shocked. ‘You seem to have an answer for everything, young lady,’ she admonished. ‘So tell me, who’s going to do all the cooking and cleaning, not to mention the shopping? We’ll need to get someone in to see to all of that. Small as it is, the house will still need to be looked after, not to mention that we’ll need someone to look after us. You’ve already told us there are only two bedrooms, so I imagine the servant will somehow have to sleep down here.’

Annie looked at her mother with pity now, but Florence was following a new train of thought as she looked round the dismal room.

‘Those wretched bailiffs have allowed us to keep so few possessions that I don’t know where to begin, but I need to start making a list of what we’ll need to buy and what the servant will need to do.’ She sniffed. ‘Not that there’s sufficient space to bring in much in the way of furniture.’ There was barely enough room for the few bits they had been allowed to salvage from their old house. Annie thought back to the morning of the previous day when she’d watched helplessly as the bailiffs piled their few bags onto a wagon that the horses then drove away. By some miracle, the boxes were waiting for them when Annie had first arrived, but they didn’t actually amount to much. Annie stood up. She couldn’t sit here and listen to more of her mother’s delusional ramblings. There were things to be done – and even if it hadn’t dawned on Florence yet, Annie understood that she and her mother were the ones who would have to do them.

She looked at the ashes in the grate that must have heated the range at the back of the room near the stairs. Perhaps the first thing she needed to do was to learn how light a fire. Not that it was cold, fortunately, but as long as there was no fire, she now realized, there wouldn’t be any hot water for tea. She went into the back yard and then into the alleyway beyond to look for some kindling and old scraps of paper which she had seen their kitchenmaid turn into a fire at home. She collected what she could and went back inside.

‘And who’s going to do the shopping and the cooking? You haven’t answered me that one.’ Florence was trailing round after her now, following her into the scullery where Annie was searching for any usable pots. ‘We’ve lost cook and the butler and all the servants,’ her mother was wailing. ‘I don’t know how we shall begin to replace them.’

To Annie’s disgust she thought her mother was going to cry again. Instead, Florence whined, ‘Who’s going to feed us?’ And she sat down again by the table once more, only this time with her head in her hands.

‘Sadly, we need to wake up to the fact that nobody but us is going to feed us, Mother.’ Annie had tried to be gentle but now she spoke more sharply. ‘We’ll have to learn how to feed ourselves.’

At that, Florence jerked up her head but before she could say anything Annie jumped in. ‘The fact of the matter is that you and I will have to learn some new housekeeping skills. I’ve already spoken to Mrs Brockett, the old lady we saw before, across the road.’ She held up her hands before her mother could respond. ‘Not that I’ve told her much about our exact position but she has agreed to try to help us. In exchange for the odd loaf of bread, she’ll give me some cooking lessons.’

Florence looked bemused. ‘Where will we buy the bread from to give her?’

‘Oh, Mother!’ Annie became exasperated. ‘That’s the whole point. We won’t buy it. We’ll make it ourselves. She’ll show me how to do it and how to cook a few simple meals. She’d help you too if only you’d agree. She has very kindly said she’ll tell me what ingredients we have to buy and where to get them and then she’ll show me how to cook them over the fire.’

Then Florence did begin to cry in earnest. She had barely been inside the kitchen in the grand house in Clitheroe except first thing in the morning when she used to check in with the housekeeper and issue orders for the day’s meals to the cook. But Annie had no time for her.

‘Oh, really, Mother, do pull yourself together.’ She could no longer hide her exasperation. ‘Here, have a look at this.’ She threw the Clitheroe Echo down onto the table. ‘Maybe you can find yourself a job this way. I know there’s not much around at the moment, particularly for women. These are depressing times, as Daddy said. The men claimed back all their jobs after the Great War so there’s precious little available for ladies right now. But you never know.’ The front page was filled with classified ads and she had ringed a few items. ‘I’m hoping I might have something lined up pretty soon. I shall be going into town this very afternoon to at least one shop where I believe there’s a vacancy.’

Florence looked up. ‘Really, darling! Some of the things you say. The very idea of it. Are you trying to shock me or something?’

Annie stared at her mother in disbelief. ‘What do you mean?’

‘I mean, how can you say such a thing? A daughter of mine even thinking of going out to work in a shop. You can’t seriously want to do that – what on earth would people say?’

Annie shook her head and gave a disdainful laugh. ‘It’s not a question of wanting to, Mother, but it’s needs must when the devil drives, you have to know that.’

‘Annie, for goodness sake. I do hope you’re not implying that it’s the devil that’s driving you.’

Annie held her breath for a moment before replying. She was afraid her mother really didn’t understand the seriousness of their situation. ‘I fear I am, Mother,’ she said eventually. ‘But the trick is: we can’t allow the devil to win.’

‘But what will you do in this “job” of yours? Where have you decided to work?’ Florence made no attempt to look at the paper. ‘I can’t read in this light without my glasses.’

Annie sighed. ‘It may not be a question of choice.’ Annie was trying to be practical and realistic, though she had no doubt about her ability to carry out any one of the first few jobs she had marked. ‘Obviously, I shall look for as good a position as possible but I may have to take whatever I am offered.’

Florence looked horrified, so Annie went on, ‘My preferred position would be as a saleslady in one of the fashionable hat shops in town. See, I’ve noted the first one here.’ They were brave words, spoken with more confidence than she felt, but Annie was frustrated that neither of her parents seemed to understand the gravity of their predicament. If her father’s wages would only cover the rent and she and her mother didn’t find a job quickly they might well be in danger of starving.

Upstairs, in the tiny bedroom under the roof, the one with the single bed, Annie crouched over the laundry bag of clothes she had managed to bring with her. Most of them she now realized would be completely unsuitable for the kind of life she would be leading in the future, but maybe she could persuade her mother to put her skill with a needle to good use in her own home first.

She picked out the smartest of the dresses she had been able to keep. It was in a soft blue wool and she thought it would be very suitable for working in a milliner’s shop. It had three-quarter-length sleeves and a nipped-in waist and she knew it was very stylish. Fortunately, only a few weeks before the bailiffs had come, she’d bought a pert little felt hat from her own milliner’s that matched the blue of the dress perfectly. She might as well wear it for the interview before she had to go through the whole shaming process once more of selling her clothes, or worse still, having to pawn them. The blue hat was really cute with a sideways-tilting brim and a small ostrich feather slotted into the petersham ribbon that ran around the base; it sat on top of her blonde sausage-curls in the most flattering way. She was glad she had thought to keep it when she had had to sell all her other lovely clothes. She didn’t know how long she would be able to hang on to it but for now at least it seemed like the perfect outfit for a job interview.

Annie set off into town where the shop was located. She didn’t have enough money for the bus fare both ways so decided she would walk back and took the bus to her destination, not wanting to appear hot and flustered even though that was how she was feeling. The sign above the door said Elliott’s Fine Millinery in gold script lettering. As she pushed open the door a bell tinkled in the distance and an older lady popped out immediately from a room behind the shop.

‘Good afternoon and how may I help you? I’m Mrs Elliott.’ The woman beamed at her as if she were a customer and looked prepared to show her an array of hats.

Annie thought she should come right to the point. ‘Good afternoon. I am here about the vacancy,’ she said. ‘I saw from your advertisement in the Clitheroe Echo that you have a retail position available. I hope I am not too late to apply?’

‘Not at all,’ Mrs Elliott said affably, although her smile faded a little, but her eyes examined Annie from top to toe. Annie met her gaze; she felt equal to any such scrutiny.

‘May I ask how old you are?’

‘I’m eighteen.’

‘That’s perfect,’ the older woman agreed.

Annie began to feel more confident. The job would be hers, she was sure of it. ‘Perhaps you would be kind enough to fill out this form.’ Mrs Elliott produced an official-looking piece of paper from under the counter. ‘It’s so that we may have your details on file.’

Annie thought this sounded promising until she actually began to write. No sooner had she written her name than she hesitated on the next line. She was tempted to give the more impressive Clitheroe address of her former home, but what if they tried to contact her and found out she no longer lived there? She took a deep breath and, with a flourish, wrote 16 Alderley Street, Norwesterly Clitheroe, before handing it back across the counter.

Mrs Elliott looked at it, the smile never wavering from her face, but when she posed her next question the eagerness had gone from her voice.

‘And what previous retail experience do you have, Miss Beaumont?’ she asked. ‘Is it in millinery or in some other commodity of ladies’ fashion wear?’

Annie felt her own smile begin to fade. ‘I-I don’t have any such experience, I’m afraid. But I’m an extremely quick learner,’ she added eagerly.

‘I don’t doubt it. But perhaps you have some other working experience that may be relevant?’

Annie realized, with dismay, that saying she had no experience of work of any kind would not be to her advantage. She wracked her brains but could think of nothing she had done in the past, other than being a valued client, that would prepare her for working in a hat shop. It hadn’t occurred to her that just being Annie Beaumont late of Clitheroe Town might not be sufficient recommendation, as it had been in the past, for whatever she decided to turn her hand to.

As the silence lengthened, Mrs Elliott said, ‘I’m afraid we must insist on taking on someone with prior ex-perience and impeccable references as I’m sure you understand. The job calls for a trained saleslady who would be able to step in and pick up the reins immediately. We don’t have the time to train someone up.’

‘May I ask how I’m supposed to gain this experience if you won’t give me a job where I could learn?’ Annie could hear the desperation in her voice and hated herself for it. It sounded almost like begging.

Now Mrs Elliott’s smile was positively condescending as she said, ‘I’m sure there are plenty of small local shops where you could gain an invaluable apprenticeship. Although not, perhaps, ones in the immediate vicinity of Alderley Street. They may not offer the kind of experience we would be looking for. I mean you could hardly expect a—’

Annie didn’t wait to hear the rest. ‘Thank you for your time,’ she said with as much dignity as she could muster. And she turned on her heel and walked out, trying to hide the burning tears of humiliation that stung behind her lids.

She had been so convinced she would be offered the job at Elliott’s Fine Millinery she hadn’t bothered to write down the addresses of the other retail positions she had seen advertised in the local paper, though she had noted they were all within walking distance of each other. So, after her initial disappointment, she set off scouring the neighbourhood to see if she recognized the names of any of the shops and if they matched the shops that had advertised they had positions available. She found two more milliners’ shops and a retail dress shop that had placed ads in the paper and at first her hopes soared when she found them. But when the shopkeepers’ reactions were similar to Mrs Elliott’s, she soon began to feel deflated. Even if they didn’t balk visibly when she gave her address as Alderley Street, Norwesterly Clitheroe, in what she now realized was the slum heart of the working-class neighbourhood, they were not prepared to overlook the fact that she had no retail experience, or indeed, experience of work of any kind. After each interview, she began to feel so disheartened it was difficult to pick herself up again ready for another one. Even when she found two more shops, one selling ladies’ underwear and one selling ballgowns, that had not been advertised in the Echo, but which had discreet postcards propped up in the window, the result was the same. After the initial question and response routine exposed her lack of experience, she turned on her heel and walked away. By the time she had visited all the retail shops that she could find that required staff, it was getting dark and she thought about the long walk home. As she turned in the direction of Norwesterly, she accepted there was no point in trying for any more similar jobs. It was time to admit defeat and look for something else.

There had been one other job in the Clitheroe Echo which had caught her attention but she had initially discounted it as not the kind of work she wanted. However, after such a fruitless day, she now realized that unskilled labour might be the only kind of work she was fit for. She knew where Fletcher’s Mill was, even though she hadn’t actually been there, for it was where her father worked in the administration offices. Not that their paths would cross if she did get the work, for the job on offer was for a loom operator, to work in the loom sheds which involved longer hours than any clerical job. The ad had said there would be training available and that, despite the long hours, she would be earning a pittance of a wage. She knew her mother would not find it palatable that any daughter of hers should have to be nothing better than a mill girl, and in this instance she wondered what her father would have to say about it too. Not that it mattered; she had tried her hardest to find more genteel work but it seemed obvious to her now that no matter how hard she tried there would be nothing forthcoming on the retail front.

The following morning, when Annie first set eyes on the sprawling complex that was Fletcher’s cotton mill, she was appalled. The only word she could think of to describe it was ‘Victorian’, but it was a far cry from the wealthy Clitheroe kind of Victorian buildings she was used to. This was a forbidding-looking compound surrounded by high walls that looked more like a prison. It was old-fashioned and out of date, a relic of the industrial revolution. As she approached the grimy, red brick buildings with the tall chimneys belching foul-coloured smoke she didn’t change her opinion. It was like taking a step back in time and she couldn’t believe she was about to put herself forward for a job in such a place. What was she thinking of? If only Mrs Elliott had been able to see beyond her lack of experience.

Fletcher’s Mill was quite some way out of the town centre in Norwesterly and the only thing in its favour, if she could get the job, was that she wouldn’t have to spend precious pennies, or too much time, travelling to and from work each day. No longer so confident that she would even be offered a job, she approached the man at the gate cautiously and asked to see the manager.

The first thing that hit her as soon as she entered the building was the hot, steamy atmosphere. There seemed to be no ventilation and, as she inhaled the dense, foggy air of the main looming shed, she knew she was making a mistake. She wanted to turn and run away while she still could, back to the fresh air and sunshine outside, but she had no choice. She desperately needed this job, any job, and for a moment she was rooted to the spot. It was like entering an alien world. The air was dense with cotton dust so that it was hard to see through the haze, and the heat and humidity made it very difficult to breathe. The fibres caught the back of her throat and made her cough.

The other thing that struck her was the noise, for what assailed her ears even before the doorman let her into the shed was the din, the like of which she had never heard before. The clatter and racket of the machinery, pounding down hundreds of times a minute, was compounded by the ceaseless whirring of a million hissing wheels rendering any kind of conversation almost impossible. As the sore, bloodshot eyes of the loom operators turned towards her momentarily, she fancied she could hear wolf-whistles even above all the cacophony. At least, she could see many lips pursed into whistle shapes as men and women alike eyed her up and down, eyebrows raised.

She was wearing what she thought of as her interview outfit and suddenly felt foolish. It might have been suitable for impressing Mrs Elliott, but it certainly wasn’t appropriate for the interview she was about to have. She wished she had thought to wear something more appropriate. But then she straightened her back and stood as tall as she could when she saw the manager coming towards her. As he negotiated his way down the narrow passageway between the looms she could see him chastising the floor workers with a flick of his finger, indicating they should be watching their machines rather than watching her. Then he directed her to the glass booth at the end of the shed that served as his office. When he closed the door, she was aware that it only shut out the highest decibel level of noise and she still had to strain to hear what he said.

Annie sat down and fanned her face with a cotton handkerchief she kept in her pocket now that she had relinquished all her leather handbags. It was unevenly embroidered in red silk with her initials. ‘Is it always so hot in here?’ she asked.

‘It’s got to be, unless you want the thread to keep breaking,’ he said.

‘Oh.’ Annie felt dismayed, but what could she say?

‘How do you like the racket?’ Mr Mattison asked, grinning as he shouted louder than necessary.

‘I don’t,’ she said. ‘But I suppose you get used to it.’ Annie’s throat already felt sore from shouting.

He shrugged. ‘There are five hundred sodding looms out there thumping down two hundred times a minute, so it’s no wonder they make such a bloody racket. And that in’t going to change either.’ He laughed a mirthless laugh, then he began to bark some basic questions at her. Annie shouted back her answers, hoping he could hear them. Then after only a few moments, she thought he said she could have the job. Under the circumstances, she wasn’t sure whether she’d heard him correctly.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.