Полная версия

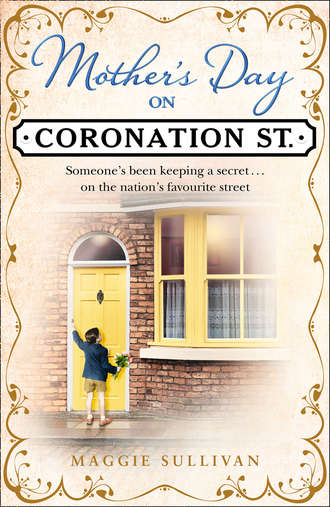

Mother’s Day on Coronation Street

The fair-haired girl glanced about her almost furtively as she stepped nearer to the bar and, when she caught Annie’s eye, it seemed as if she might turn and run out again. But then a resolute look crossed her face and she made a strange sight as she walked up to the counter in a determined manner. Large black shoes flapped out beneath a blue serge skirt, so that it looked like the old-fashioned Edwardian style. The skirt’s coarse material was gathered at the waist under a stiff buckram band that seemed to be cutting her in half and the whole thing looked like a hand-me-down because it was too big and much too long for her, far longer than the current fashion dictated, given the limited availability of fabric. A tight, rib-knit jumper with several holes in it flattened whatever there was of her breasts. The girl’s hands were hidden from view, plunged into the two side pockets, and a small wooden box was tucked under one arm.

‘Can I help you? Annie asked in the most superior voice she could muster. Now that she was close to, she felt as if there was something familiar about the girl’s face. Was it the unusually high cheekbones that didn’t seem to have much flesh on them, or the narrow chin giving her a diffident, almost impish, look that Annie was sure she had seen before?

‘I’ve not come to drink,’ the girl said, ‘if that’s what you’re thinking.’

Annie’s laughter was steeped in sarcasm. ‘I should hope not, young lady. I don’t know who you are, but one thing I do know is that you are far too young to be in a pub at all. Now I must ask you to leave or they’ll be after my licence.’ The girl glanced down. She had released her hands from her pockets and was twisting her fingers awkwardly, only stopping now and then to pick at the cuticles. Her hands looked red and sore; Annie’s response had obviously unnerved her and she suddenly seemed unsure.

‘You’d better leave quietly before I get cross.’ Annie made a waving motion in the direction of the door but the girl didn’t move. She plunged her hands back into her pockets.

‘I’ll go as soon as you’ve answered my question,’ she said, her voice suddenly strong.

‘Oh, and what question is that?’ Annie sounded amused.

‘Is your name Anne?’ she asked. ‘I’m looking for someone called Anne.’

Annie’s first reaction was to raise her eyebrows in astonishment. As the landlady of the Rovers Return she was not unknown in these parts, but she would never have expected a young girl to march in and ask for her by name like that. Then she frowned. She tilted her head trying to get a closer look at the girl’s face; there was something familiar about those cheekbones …

‘And who …’ Annie began. But the girl cut across her.

‘Did you used to work at Fletcher’s Mill?’ the girl asked.

Now Annie’s jaw fell open and for a moment she was speechless. Nobody knew about the time she’d worked at the mill. Except for her mother and Jack, of course, but the shame of it would preclude Florence from ever disclosing the fact to anyone. She glanced round the room. Quite a few of the locals and several GI soldiers still lingered, though to her relief no one seemed to be listening to what the girl was saying.

‘I think you’d better come this way,’ Annie said abruptly, her voice stiff and unnatural, and lifting the velvet curtain she led the way through the little vestibule that lay behind it, and into the living room.

Gracie had seen the young girl enter the bar and was unsure what she should do so she was pleased that Annie had not yet gone upstairs and was still around to deal with her, but she was surprised to see Annie usher her into her private quarters. Annie had been looking tired before the girl appeared and was looking even more so after speaking to her. Gracie wondered who she was. She collected all the dead glasses and went to attend to Mrs Sharples, who had just banged her pint pot on the counter demanding immediate attention in her customary way. Gracie recognised the girl’s face. She had seen her hanging round outside on her way into work but when Gracie had tried to smile at her she had quickly looked away. She had been carrying a small wooden box with her then and she was carrying it now. What could she want with Annie Walker, she wondered? What would she give to listen at the living room door in the vestibule!

‘A pint of stout when you’ve finished dreaming.’ It was Ena Sharples. Her reputation went before her and Gracie was anxious not to cross swords with her.

‘Oh, sorry,’ Gracie said. ‘What can I get you?’

Ena shook her head at Gracie’s forgetfulness, but for once she just pointed at the row of black bottles and didn’t say anything.

Annie gathered herself in the time it took to usher the girl into the room and settle her in to a chair. It took a few moments but finally her breathing rate returned to normal. She would have welcomed any excuse to leave the room while she collected her thoughts. But she knew she couldn’t do that.

She sat down opposite the girl and entwined her fingers so that her hands lay passively in her lap.

‘Now then, young lady,’ she said and smiled benignly, ‘who are you exactly? And what is it you want to know?’

‘I want to know if you’re Anne Beaumont. It’s not such a difficult question, is it?’ The girl lifted her chin and tried to sound defiant but it was obvious her bubble of initial confidence was beginning to deflate as Annie’s gaze didn’t flinch. ‘My name’s Annette, Annette Oliver,’ she added looking away.

Annie’s brows knitted together. The name didn’t immediately mean anything to her, but the similarity to her own name was not lost on her. ‘Am I supposed to know you?’ she asked.

The girl shrugged. ‘Dunno.’ She looked as if she was going to say something else but then changed her mind.

Annie’s eyes were then drawn to a white lawn handkerchief Annette was pulling out of the box that had been under her arm. She could clearly see the initials that had been embroidered in the corner in red silk thread. AB. Now it was Annie’s turn to look uncomfortable. She visibly blanched. ‘Where did you get that?’ she asked, her voice sharp now.

‘It was in this box the orphanage gave me now I’m old enough.’

She passed it to Annie, who held it loosely in her fingers as if she were afraid to touch it. Then she let it fall into her lap. Even though her eyes had misted she could recognize the unevenly embroidered stitching and the sight of it brought back floods of unwelcome memories. She looked at the girl from under hooded lids. Annette was almost twelve years old, she’d said. Annie did some quick arithmetic and sat back in shock. She looked again at the handkerchief and her breathing quickened. Then she looked at the girl. There was something familiar about the girl’s face, though she couldn’t quite put her finger on what.

‘I grew up in the orphanage, no one ever knew my mum or dad.’ It was Annette who broke the silence. ‘And for some reason they thought I should have the box on my twelfth birthday. It was the only thing that was left with me, apparently, when I was abandoned in a shopping basket outside the gates. I was only a baby, just a few days old, one of the staff once told me, but no one had any idea where I came from.’

‘That’s very sad,’ Annie said.

‘I suppose it is, but it’s all I’ve got. That handkerchief’s my only clue, really. You recognize it, don’t you? I can tell the way you was looking at it.’ The girl was staring at her disconcertingly and Annie began to feel uncomfortable.

‘There was a dummy and a rattle in the box as well,’ Annette went on. ‘But they had no marks on them to say where they came from. Or where I came from, for that matter.’ Annette stopped and stared directly at Annie. ‘I was hoping the rattle might be silver so’s it could make me rich.’ She shook her head. ‘No such luck, though.’ Annette gave a little smile. ‘It’s shaped like a man in a funny hat and it’s got bells hanging from it. Mean anything?’

Annie looked at her, her expression blank. She didn’t know what to think. She shook her head slowly. Though she was still wracking her brains about what was so familiar about the girl’s face.

‘The box has a letter in it too, telling me to go look for Anne Beaumont. I haven’t had much time lately because I’ve started working after school and most weekends as a scullerymaid in Grant House on the edge of the big park in Cheshire.’

‘But that’s miles from here.’ Annie lifted her head and looked with pity at the young girl.

‘I know. But whenever I gets a day off I goes looking. And though I save what I earn to help pay fares, I usually have to walk most of the way so it takes me a while. But I do what I can. I really wanted to find you.’ She hesitated. ‘That’s supposing … you are Anne Beaumont?’ She peered directly into Annie’s face, as if she was hoping to recognize something, some specific feature.

Annie didn’t answer. She looked down into her lap and fingered the white lawn square. What was Annette reading into this, she wondered? She shifted uncomfortably in her seat, feeling agitated and unsure. How did Annette think she was related to AB?

‘Do you want to see the letter?’ Annette stood up and carefully unfolded the fragile piece of paper into Annie’s lap. Then she stood behind her so she could read it over Annie’s shoulder. ‘See?’ She pointed a red, swollen finger. ‘See there, it says I’m to contact Anne Beaumont from Clitheroe. That is you, init? I know I’m right.’

Annie picked up the delicate letter by the corner. It looked as if it had been torn from a notebook. She turned it over but there was nothing written on the back. The letter wasn’t signed and she didn’t recognize the tiny scrawl. Finally, she gave a little nod.

‘Yes, it is me,’ she said. ‘Beaumont was my maiden name. But … but I don’t know how my handkerchief ended up in your box. I … I don’t know anything about your mother,’ she said softly.

Annette stiffened.’

‘The trouble is …’ Annie hesitated. ‘I don’t know how you think I can help you.’

Annette didn’t reply.

‘Do you know who wrote the letter? You do realize it could have been written by anybody?’ Annie said.

Annette hung her head. She sighed and her shoulders dropped as she turned away and slumped back into the chair.

‘I’ve been looking for you for ages,’ was all she said then.

‘But the fact that your letter mentions me by name is no proof that I’ve any connection with your mother,’ Annie said, ‘or that I even know who she is. For all we know, it could be a different Anne Beaumont entirely.’

‘I suppose so.’ Annette sounded dejected. She leaned forward and put out her hands in a pleading gesture. ‘But I’ve got to find out about her. I’ve got to know where I come from and the letter says you could help …’ Her voice cracked and a tear plopped onto the carpet.

‘Are you sure you—’ the girl tried again, but Annie cut in sharply, ‘The letter is wrong.’ Her voice was firm, but then she saw the despondent look on the girl’s face and Annie had to look away. ‘I’m truly sorry, Annette,’ Annie said sadly, ‘but I’m afraid I can’t help you.’

Gracie was pulling a pint of Shires for Albert Tatlock when the bedraggled young girl finally came out from Annie’s living quarters, the small wooden box still tucked under her arm. Gracie watched her make her way to the door, her shoulders slumped. Annie was only a few steps behind her, as if to make sure she didn’t turn to come back into the bar. Gracie thought Annie looked a lot paler now than she had before and somehow even more weary, though her jaw seemed set in a kind of grim determination. Neither she nor the girl spoke so Gracie was left to wonder who the stranger was and what she had wanted.

As soon as Annette had gone, Annie climbed the stairs as fast as her unsteady legs would carry her but she stood uncertainly on the landing for a few moments, remembering the feel of the handkerchief, seeing again the words of the letter. Her legs were trembling and she had to work hard to control her breathing as her mind was flooded with memories. She gripped hold of the bannister and opened her eyes wide, hoping the sight of the vase of silk flowers tucked into the recess on the landing would help to shut out the images that assailed her.

Annie felt sorry for Annette. How dreadful not to have any idea who your parents were. She had seemed a nice enough child, but Annie really hoped she would never have to meet her again. For Annette, even in her short visit, had managed to rake up so many painful memories of heat and lung-filling dust, memories of long, uncomfortable hours in a loom shed; memories Annie would rather forget.

Chapter 3

1927

Annie was eighteen years old when she went to work in Fletcher’s Mill; not something, even in her wildest imaginings, that she had ever thought she might be doing. Her dreams had been of stage and screen stardom. She had assumed she would be living the life of a lady, once she had secured a good marriage to some rich eligible young man, someone who matched the standing of her own prestigious background, and she had never thought beyond that. But then their family fortunes had changed dramatically and their status and upper-middle- class life style had disappeared overnight.

When she saw her parents being unceremoniously dumped out of the back of their erstwhile gardener’s old wagon and left at the front door of the two-up, two-down terraced cottage on the poorest side of Clitheroe, Annie rushed out of the house to greet them. She could see at once how hard this was going to be for them to grasp that this was, for the foreseeable future, to be their new home.

‘They can’t expect us to live here!’ Edward Beaumont stood, shoulders hunched, amid the straggling weeds on the moss-ridden flagstones. The bowler hat he was clutching seemed so out of place he didn’t try to put it back on and he scratched his almost bald head in puzzlement.

‘Who’s “they”? Annie asked wearily. She knew what her father would say, but she thought that hearing him put voice to the words might help all of them to make sense of their plight.

‘The authorities … the mill owners … Oh, I don’t know. Whoever owns these kinds of places.’ He gestured towards the front door in exasperation.

Annie shrugged. ‘Why shouldn’t we have to live here? It’s no worse a house than lots of people live in.’ She was feeling wretched and deflated but was determined not to show it in her parents’ presence.

Having arrived first and already explored what she could only describe as a doll-sized house, she felt helpless and knew they would too. She had never been to this part of the town before and now she was here she knew why. Inside herself she was feeling as lost as her parents were. They were all still trying to make sense of what they had been reduced to, to work out how their fortunes had turned so completely around, but Annie thought it politic to try to put on a brave face.

‘I’ve had a little time to have a look around before you came,’ she said, ‘and from what I’ve seen and heard from the neighbours I think this one’s a step up from what some people have to put up with round here.’

‘What do you mean by a step up? We would never have let one of our tenants live in a hovel like this, never mind us. This is nothing but a working-class slum that should have been cleared years ago,’ her father blustered.

‘I suppose even the working classes have to live somewhere, and if they don’t have enough money to do them up—’ Annie began.

‘But we’re not like those lower sort of people,’ Florence cut in, ‘and we can’t live in a place like this.’ She sounded most indignant. ‘We can’t be expected to live amongst them.’ Now she was openly dismissive. ‘Just because we have no money doesn’t bring us down to their level, you know.’ She flapped her arms vaguely, as if to dismiss the whole neighbourhood. ‘It doesn’t matter what our financial situation is, we could never be considered to be the same as the labouring classes. They are of a completely lower order. That is just the way it is.’

There was an old lady sitting on the doorstep of one of the terraced houses opposite, with some tired-looking knitting in her lap. She must have thought Florence was waving and she waved back.

Florence tossed her head in disgust and turned away. But Annie waved to their new neighbour and gave her a tired smile. ‘That’s Mrs Brockett, that old lady over there,’ Annie said. ‘She’s lived here all her married life. She’s actually very nice.’

Florence peered down her nose and looked at Annie as if she was mad. ‘How on earth did you come to that conclusion? The poor old thing looks like she’s a permanent fixture in that chair.’

Annie laughed, trying to lighten the mood. ‘You’re right there, Mother. I think she sits out on the doorstep every day unless it’s raining, but I had a chance to chat to her before you arrived.’

‘Did you, indeed?’ Florence didn’t look impressed and she actually shuddered.

‘As long as we’re stuck here she might turn out to be a very useful lady to know. She seems to know most of what goes on in the street,’ Annie said.

‘I hope you didn’t tell her any of our affairs?’ Florence’s reprimand was as swift as it was sharp. ‘I know I certainly shan’t be giving her the time of day.’

Annie ignored her mother. ‘She thinks we’re very fortunate that we have our own lavatory and she says we should be grateful we have a tap for water actually in the kitchen.’

‘Grateful? For a lavatory and running water? Are you mad, girl?’ Now her father spoke up. ‘This is the end of the 1920s. Surely everyone has water and water closets these days?’

‘It seems not,’ Annie said carefully. ‘Not round here at any rate. But, apparently, it’s a real bonus having our own lavatory, just for the family’s use. Although …’ She hesitated, thinking of their old home. ‘It is outside.’ She tried not to pull a face as she said this for she didn’t want to tell them just yet that it would need a jolly good clean before any of them could think of using it. ‘Apparently,’ she thought she’d better add, ‘many of the houses in these terraces have to share a toilet with half the street. And there are several who have to carry their water indoors in buckets that they fill from some kind of communal standing pipe in the yard.’

Annie thought her mother was going to faint when she said this, so she quickly pushed open the front door and ushered them inside. But that didn’t improve either of her parents’ demeanours. Florence looked so lost and bewildered standing in the middle of the single downstairs room that was to serve as a living room-cum-kitchen for the three of them that Annie almost felt sorry for her. But when Florence wailed, ‘We can’t possibly live here! There’s no room for anything,’ Annie thought she would lose patience. She watched Edward and Florence as they stood regarding the few meagre items they had begged to salvage from the bailiffs, while the rest were ignominiously sold, together with the bedding they had been allowed to keep. The few selected items of clothing they had clung on to had been bundled up like rags and lay discarded by the front door.

‘At least there’s two separate bedrooms upstairs,’ Annie said quickly, hoping to distract them. ‘They’re off a small landing.’ She indicated the stairs at the back of the room.

‘And where will the servant sleep?’ Florence enquired.

Then Annie’s patience snapped. She felt so exasperated at her mother’s inability to grasp the magnitude of the tragedy that had befallen them that she thought she was going to scream out loud. She herself was struggling to understand what had happened to them, but how could she get it into her mother’s head that life was never going to be the same as it had once been? When Florence began to cry, it was all Annie could do not to strike out and hit her. Surely she, as the child, was the one who needed her parents’ support?

‘Shall I show you the bedrooms?’ Annie said, gritting her teeth. ‘Then you can see for yourself exactly how much room there is.’

Florence shook her head. ‘Not just yet, dear. I haven’t the strength.’

There was a wooden table and a bench and two chairs that had been left by the previous tenants by the window in the front room. Florence wiped the seat of one of the chairs with her white lawn handkerchief and sat down. She also tried to wipe away the powdery film of dust that covered the scratched wood of the table, but when she leaned against it the table wobbled back and forth, so she pulled back, sitting up as straight as she could. Edward sat in the other chair without paying heed to the dust that was being transferred from the splintered wooden seat to his best Crombie overcoat. Annie kept her back as erect as possible when she took a place on the bench.

They all stared in the direction of the window, though it was too grimy to see out of it. Suddenly, there was a wailing sound that made Annie jump.

‘What’s going to become of us?’ It was Florence who had cried out. ‘And what’s going to happen to our lovely home? Who’s going to look after it until we’re ready to go back?’ She prodded her husband who was sitting beside her, looking bemused. ‘We can’t desert it now, Edward. It’s been in your family for generations.’ She shook her head from side to side as though in disbelief. ‘The beautiful summerhouse and the old oak tree down by the lake … I know how much you love it all, Edward. Will the gardener really look after it while we’re away? How much will he do if you’re not there to prod him and remind him?’ She covered her face with her hands for a moment.

‘You can ask my father about the house and the estate when you next see him,’ Edward growled angrily. Scowling, he kicked a piece of garden rubble from where it had stuck to his shoe to the other side of the stone floor.

‘Don’t be disrespectful of the dead.’ Florence sounded horrified.

‘What respect did he show me when he left me the legacy of all his debts? Don’t call me disrespectful, madam, when it’s me who’s had to sacrifice the family inheritance to pay off his creditors. When it’s me and my family who’ve been reduced to this.’ He looked round the room in disgust. ‘How can you respect someone who, despite his years, still had no idea what made for a good business deal and what made for a bad investment?’

‘I always thought Grandpa was rich,’ Annie intervened, for she recognized the expression on her father’s face as one that meant they were in for a long harangue.

‘He was when I was a young lad. But I was too young to understand that money was leaking out of the estate faster than it was coming in. As I grew older, if ever I questioned anything, he always found ways to cover up his incompetence.’ Edward closed his eyes and took a deep breath. ‘I can’t say I blame the family entirely for turning their backs on us. I suppose we must look like a piteous lot.’

At this Florence had a fresh outburst of tears. ‘Not one of them put out a hand to help. I wouldn’t have expected the bailiffs to show much sympathy, but Edward, your own brothers? I ask you.’

‘I know.’ Edward sounded resigned. ‘Charity begins at home, I told him. But that meant nothing to him. He was too busy feeling smug about how he had managed to hang on to his own fortune that, fortunately for him, had nothing to do with the family’s money.’

‘Uncle William was in the same position but at least he did find you a job,’ Annie chipped in.

‘Doing what?’ Edward was scornful. ‘As a clerk at a mill?’

‘A senior clerk,’ Florence corrected him.

‘A clerk nevertheless,’ he repeated. ‘At Fletcher’s Mill. In the worst part of Clitheroe I’ve ever seen.’

‘At least Uncle William was true to his word,’ Annie said as patiently as she could. ‘You said the mill does have a job for you?’

Edward nodded. ‘I suppose that’s something. I understand there’s not much work about these days.’

‘I know,’ Annie said. ‘The country is still struggling from the disastrous financial effects of the war and it’s affecting everyone.’

‘But what do I know about cotton mills?’ Edward was still grumbling. ‘I’ve never done a day’s work outside of the estate in my life. All I know is about managing smallholdings and woodlands, supervising the gardeners, and collecting the rents from the tenants’ cottages. That’s my line of work. Not cotton mills.’ He got up and stomped round the room.