Полная версия

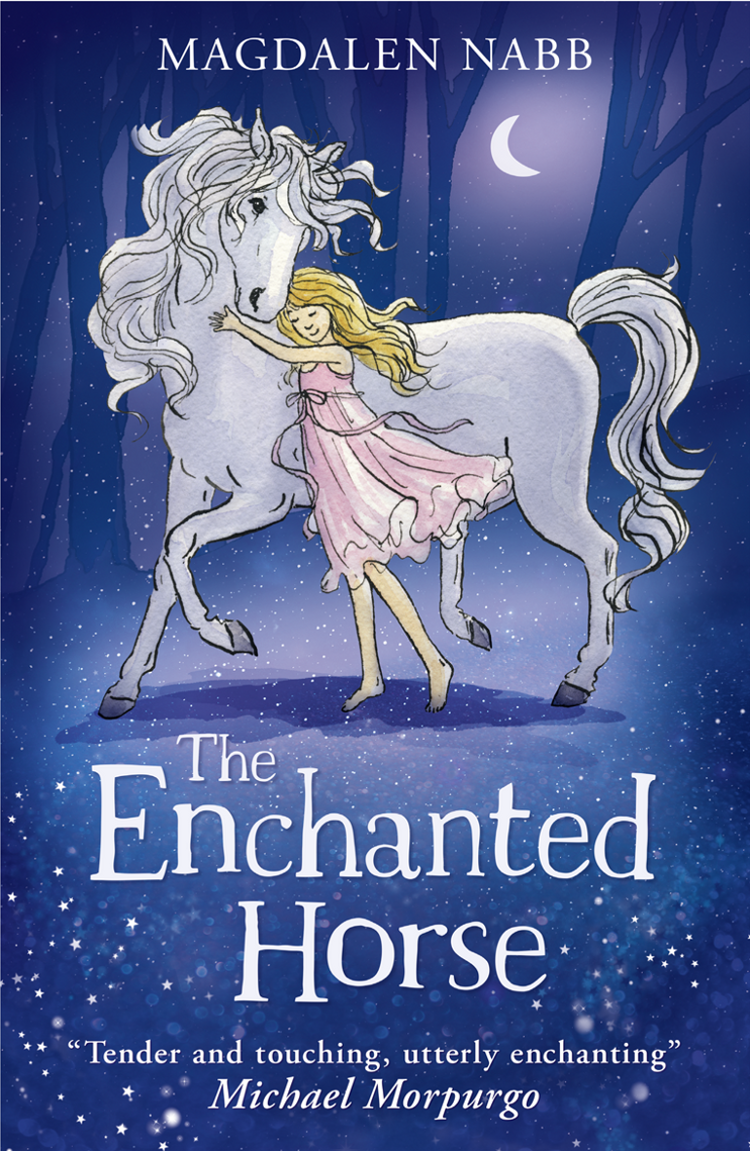

The Enchanted Horse

Copyright

First published in Great Britain by Collins in 1992

This edition published by HarperCollins Children’s Books in 2014

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd,

77-85 Fulham Palace Road,

Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Text copyright © Magdalen Nabb 1992

Illustrations copyright © Julek Heller 1992

Why You’ll Love This Book copyright © Michael Morpurgo 2009

Cover illustration © Susan Hellard

Magdalen Nabb asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007580293

Ebook Edition © 2014 ISBN: 9780008104863

Version: 2014-11-19

This book is dedicated to Maestro Nino di Fazio with admiration for his boundless knowledge of horses

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Keep Reading …

Why You will Love this Book

Also by Magdalen Nabb

About the Publisher

It was Christmas Eve, and the afternoon had frozen as hard and milky as a pearl. The sun was as thin and pale as a disc of ice in a sky as white as the snowy ground.

Irina walked in front of her mother and father along the lane that led across the fields to the village. She was dressed in a sheepskin coat and boots and mittens and a sheepskin hat. Her long fair plait hung down beside her. The cold pinched her thin cheeks, and the trees that grew on each side of the lane poked their black fingers through the freezing fog as if they were trying to clutch at her as she went by.

Even before they reached the first houses at the edge of the village, Irina heard the faint sound of a band playing Christmas carols. But she didn’t look up and smile or turn to say “Listen!” to her mother and father. She only walked quietly on, looking down at her thick boots as they trod the hardened snow. Irina didn’t like Christmas.

When they reached the village, all the shop windows were already lit, making haloes of light in the fog. The snow-covered square where the band was playing round the Christmas tree was hung around with coloured bulbs. But Irina and her parents didn’t stop to listen to the carols because they had so much to do. They lived on a farm and at Christmas everyone wants more cream and eggs and milk, and besides, they had to be back home in time to feed the animals. So her father stopped to talk to the dairyman at the corner and Irina went ahead with her mother to help with the shopping.

They went to the baker’s to buy bread and flour and had to wait in a long queue. At the front of the queue a girl who was smaller than Irina reached up and pointed at the cakes and little pies sprinkled with icing sugar.

“And some of those,” she shouted, “for Grandma! And the big cake! Grandpa likes cakes! The big cake!”

Irina watched her and listened to every word, but when it was her mother’s turn she didn’t ask for anything. She was thin and never had much appetite and there was no Grandpa or Grandma coming for Christmas dinner.

They went to the greengrocer’s and waited in the long queue. A fat little boy with a red scarf wound round and round his neck was quarrelling with his older sister.

“I like dates best!” he protested.

“No you don’t,” his sister said, “you only like the box with the picture on it, and we’re going to buy figs and nuts and tangerines, so there.” And their mother winked at the greengrocer’s wife and bought figs and nuts and tangerines and dates.

Irina watched them and listened to every word, but when it was her mother’s turn she didn’t ask for anything. She had no brothers or sisters to quarrel with.

The band in the square began to play “O Come, All Ye Faithful” and the fat little boy in the red scarf and his sister joined in the singing as they went out.

It was getting dark, and the coloured lights twinkled brighter now against the shadowy snow. On the corner outside the greengrocer’s shop a fat lady with a long apron and thick gloves was selling Christmas trees. A thin boy, taller than Irina, was choosing one with his father. “This one! No, this one, no, that one, that one, it’s the biggest!” and his father laughed and said, “And how do you think we’ll get it home?” But he bought it, even so, and the fat lady wound some thick string round it to help them carry it. Irina watched and listened but she didn’t ask for anything. Years ago her mother had said, “You’re too old now to be bothering about a Christmas tree. It’s a waste of money. You can choose a nice present instead.”

So they walked past the Christmas trees and crossed to the other side of the square. There was a toy shop there, and next to that a gloomy junk shop with a bunch of dusty mistletoe hanging in the window, and next to that a shop that sold pretty frocks with full velvet skirts. Irina stood beside her mother and stared at the shop windows with bright eyes but she didn’t ask for anything. What was the use of a party frock when she lived so far from the village that she never went to a party? And what was the use of toys when there were no children near enough to play with?

“Have you thought what you’d like?” her mother asked. “You know we mustn’t be long, we’ve a lot to do.”

Irina tried to think. It’s nice to be able to choose anything you want but it’s nicer still when your present is a surprise. So she stared at the big dolls in boxes and then at the dresses and then at the tinsel and the silver bells decorating the window. She wanted to choose something that would please her mother. Then she remembered the fat little boy and his cheerful red scarf and so as not to keep her mother waiting and make her angry she said, “I like the red velvet frock …”

“And where do you think you’ll go in it?” said her mother impatiently.

“I don’t know …” It’s hard to please your mother when you don’t know exactly what she wants you to say. Then she turned and saw her father coming.

“Well?” he said. “Have you finished shopping? It’s about time we were getting back.”

“Irina hasn’t chosen her present,” said her mother crossly. “And to look at her face you’d think it was a punishment instead of a treat.”

Irina wanted to say, “I don’t want anything. I’m not asking for anything. I’d rather go home.” But she didn’t dare.

Then her father said, “Come on, let’s have a look in that toy shop. There must be something you’d like.”

“She’s spoilt, that’s what she is,” her mother said. “She doesn’t know what it means to want for anything.”

The band in the square was playing “Silent Night” very quietly. The sadness of the music, the growing darkness, and the cheerfulness of all the other families made Irina want to cry.

“I don’t want anything,” she said to herself fiercely, “I don’t—” But just as they were coming to the toy shop she stopped.

“Come on,” said her father, “you’re not going to find anything there.”

But Irina didn’t move. She was staring in through the window of the junk shop, trying to make something out in the gloom.

“Irina!” said her mother. “For goodness’ sake, we have to get home.”

But Irina, always so quiet and obedient, for once took no notice.

“The horse …” she said, “look at the poor horse.”

“What horse?” said her father.

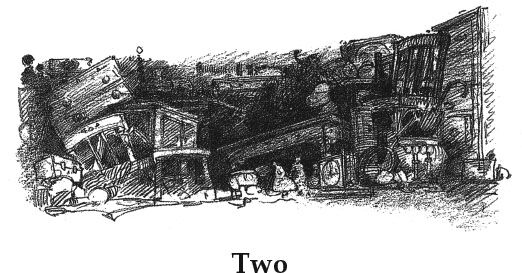

“I can’t see any horse,” said her mother. And they both peered into the gloomy junk shop. Beneath a jumble of dusty broken furniture they could just make out the head and tattered mane of what was probably a rocking horse.

“I see it now,” her father said. “Well, come on, let’s get on. You don’t want that old thing for Christmas.”

“I should hope not,” her mother said. “It looks filthy.”

But Irina stared up at them bright-eyed, and the tears that had started with the sad carol and the growing darkness and the cheerfulness of all the other families spilled over and ran down her cheeks.

“It’s being crushed,” she cried. “It’s lonely and frightened and being crushed under all those things!” And before her parents could stop her, she had run inside the shop and all they could do was to follow her.

Once inside, Irina stood still, wondering what to do. She’d never seen such confusion in a shop before. It didn’t really look like a shop at all, more like the untidiest house in the world. The piles of old furniture reached right up to the ceiling and it was difficult to pass between them. There were ornaments, too, and brass buckets and lampstands and old stoves and typewriters and objects you couldn’t tell the use of, and everything was thickly coated with dust, including the one bare light bulb which left most of the room in shadow.

“What can I do for you?” asked a voice in the gloom.

Irina looked about but she could see no one. She felt frightened, but she stood where she was and waited.

“Anyone at home?” said her father’s voice behind her.

A voice chuckled. “I am,” it said, “if you want to call this home. Past the big dresser on your left.”

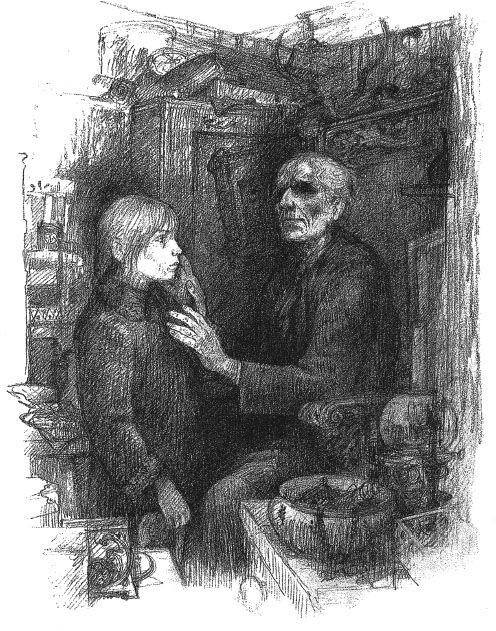

Irina looked round. At first she could make nothing out but then she noticed a huge armchair with carvings on it as big as a throne, and the profile of a man’s head just visible.

“See me now?” But the head didn’t turn and the eyes were shut. “I suppose it’s getting dark, but I can’t see and I don’t know why I should pay out good money so that others can see. There’s nothing much worth looking at, though I make a living after a fashion. What was it you wanted?”

“The rocking horse,” Irina said, as loudly as she dared, and she went closer to the huge carved chair. The man seated there was almost as small and slight as herself, and his closed eyes were sunk in his white face so that he seemed to have no eyes at all. He wore a black overall and his pale hands rested on his knees as quietly as mice.

“Irina …!” protested her mother in an angry whisper. Irina stood where she was, her fists clenched in fear and determination.

“She saw the horse in the window …” Irina’s father began, but the blind man took no notice of him.

“What’s your name?” he asked, his face lifted towards Irina.

“Irina.”

“Irina,” he whispered. “Come closer to me.”

Irina was frightened of the blind man, but she had to rescue the horse. She went closer. The blind man lifted his mouse-like hands and touched her face, feeling her eyes, her thin cheeks, her mouth and her chin in turn.

“Irina,” he said again, and he patted her face gently. “You’re a very sad little girl. Why don’t you play and be happy?”

“Because there’s nobody to play with,” Irina said.

“And that’s why you want Bella? To play with?”

At first Irina didn’t answer because she didn’t know who Bella was, but then she thought and said, “Is Bella the name of the horse in the window?”

“That’s right,” said the blind man.

“Then I don’t want her to play with,” said Irina boldly. “I want to look after her because she’s dirty and lonely and crushed under all those heavy things in your window.”

“In that case,” said the blind man, “you’d better take her home with you.”

Irina stood still and waited, wondering if her mother would say she couldn’t, but nobody spoke until the blind man said, “Would you like to know why I call her Bella?”

“Yes,” said Irina. “Did she belong to another girl who called her that?”

“I don’t rightly know,” the blind man said, “who she belonged to, but I’ll tell you her story, such as it is. Do you remember a wicked farmer who used to live hereabouts who was known as Black Jack?”

“No,” said Irina, “I don’t.”

“Well, well,” said the blind man, “you’re very young and it was all before your time.”

“I remember him,” said Irina’s father, coming closer. “He kept horses.”

“He did,” said the blind man. “And the most beautiful one of all was named Bella because Bella means beautiful. But he was an evil man and treated his animals badly, very badly. They never got more than a handful of oats a day, barely enough to keep them alive, and Bella, who was as finely bred and elegant as a racehorse, was forced to pull him around in that dirty old cart of his. They say he whipped her until she bled. No one knew where he got her, but some said he captured her himself from a wild herd that sometimes passes by this way.”

“And what happened to her?” Irina asked.

“I don’t know,” the blind man said. “But I can tell you what happened to Black Jack. He died.”

“I remember,” said Irina’s father. “I went to the auction when his farm was sold. My old father was still alive then and he kept a pony and trap himself. It was he who talked me into going, but there was little enough worth buying and the horses were only fit for the knacker’s yard.”

“Even Bella?” asked Irina.

“Bella wasn’t there,” the blind man said, “Bella wasn’t there. I asked about and I spoke to the auctioneer himself but there was no horse of that description on his list. Poor creature. Poor beautiful creature …”

The blind man fell silent with his thoughts as if he’d forgotten there was anyone there.

“Was she dead, then …?” whispered Irina after a while.

“I bought all that stuff in the window from Black Jack’s place,” the blind man said, without giving her an answer, “and there it’s been ever since, including the horse.”

“Now what would Black Jack have wanted a rocking horse for?” wondered Irina’s father. “He had neither wife nor child.”

“But that’s just it,” said the blind man very softly, just as if he were talking to himself. “It’s not a rocking horse.”

Then he spoke more loudly, turning his face up towards Irina’s father’s voice.

“Take the horse home for your little Irina,” he said. “If it will make her happy I don’t want anything for it. Only perhaps you’ll have to come for it another day when the boy who helps me is here. You understand. I can’t move all that stuff to get at it.”

“That’s very nice of you,” said Irina’s father. “We’ll call another time.”

He took Irina by the shoulder, but Irina, who never asked for anything, cried, “Please! Please can we wait in case he comes?” And she touched the blind man’s arm, no longer afraid of him. “Please let us wait! You can tell us more stories about Bella.”

“Come on now,” said her father, and he led her to the door. “You know we have to get home.”

“And don’t imagine we’re coming back,” warned her mother as they went. “That filthy thing must be a mass of woodworm and it’s not coming into the house.”

Outside on the snowy pavement Irina began to cry. The band was still playing under the Christmas tree and the people had finished their shopping and were starting for home loaded with parcels and calling to each other under the winking lights.

“Merry Christmas! Merry Christmas to you!”

Before her parents could take her away, Irina turned her tearful face for a last look at Bella’s poor head, crushed under all that junk, and then from inside the shop the blind man’s voice called out, “Stop!”

It was as if he had given an order that had to be obeyed. Irina’s parents hesitated and looked at each other.

“Come back a moment, if you will.”

Irina’s father shrugged. “I suppose we’d better see what the old chap wants.”

They went back inside the gloomy shop and Irina ran straight to the blind man’s chair. He was sitting just as they’d left him, with his hands resting quietly on his knees.

“I never mistake a footstep,” he said. “When you can’t see you learn to recognise people in other ways.” Then he lifted his face up and called, “Hurry up now! We have customers waiting!”

Irina turned round, and saw a tall cheerful boy come in from behind where her parents stood watching.

“I came to wish you a Merry Christmas, Grandad!”

The grinning boy spoke at the top of his voice as though the man were deaf rather than blind.

“And just as well you did,” said the blind man, “there’s a job for you to do. This is Irina, and she wants to take Bella home with her, so you’ll have to get her out from under all that stuff in the window.”

“Right you are, Grandad!” said the boy.

“I don’t think …” began Irina’s mother, but the boy had already climbed into the window and was heaving the broken furniture about. “I’ll have her out of here in two minutes!”

“Is he your grandson?” asked Irina shyly.

“No,” said the blind man, “but that’s what he likes to call me.”

“I haven’t got a grandad,” Irina said, and she stared at the blind man, wishing he were her grandad, because he could make her parents do what he told them.

“Here you are!” said the boy, and he set Bella down on the floor by Irina. She touched the dirty tangled mane timidly.

“Your father will carry her home for you,” the blind man said. “She’s too heavy for you.”

And sure enough, without a word of protest, Irina’s father came and picked up Bella.

“She’s a fair weight,” he said, “but I’ll manage.”

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.