Полная версия

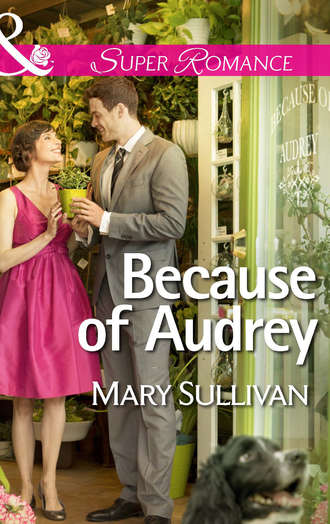

Because of Audrey

“What kind of business?”

“Importing computer parts for the government.”

With a glance, she checked out his suit. Why on earth was he wearing one at eight in the morning? A simple pair of jeans and a T-shirt would have sufficed. Did he even own jeans?

His rumpled tie, the unbuttoned collar of his shirt, the hair that sported rills where it looked as though he’d run his fingers through it impatiently, scorned his casual arrogance. Maybe Gray wasn’t as together as he’d like her to believe. But if not, why not?

“The business is lucrative, I take it?” she asked. The suit looked like it cost big bucks.

He nodded. Of course. Gray would make a success of anything he touched. Golden boy. His surface confidence nearly unnerved her. Nearly, but not quite. She’d seen him at his worst, naked, both literally and figuratively. She knew he put his pants on one leg at a time, just like any other man. She knew exactly how vulnerable Grayson Turner could be.

He glanced around the greenhouse, his gaze seeming to linger on the timeworn corners of the old place. Humid streaks trailed the inside of the glass walls. So what if it looked bad? She would fix it all when she had money. “So,” he asked, “what’s so important in here that you locked yourself to the door?”

“My life.” She decided she might as well come clean and let him see exactly how kooky she was. “These—” she swept an arm wide to encompass the tables of seedlings and plants she nurtured like vulnerable infants “—are my babies.”

He quirked one eyebrow. “Babies?”

Her natural defiance kicked in, and she lifted her chin and nodded.

“This is what you do for a living?” he asked. “I thought you did something with rocks.”

“I did. I was a geologist for thirteen years. I decided to come home to open a floral shop.”

“Why? Geology would probably pay more than the income from a flower shop in a small town.”

“After all these years, there’s still a glass ceiling for women in certain industries.”

His swift glance down her body spoke of things he wouldn’t express overtly. Again, his disdain. “Did you dress like that on the job?”

“I expressed my individuality.” She’d been defiant at work, yes, but she’d done a hell of a good job. “I paid a price for it. I worked for thirteen years at something that should only ever have been an avocation. Collecting rocks was a hobby and should have stayed that way, but I made enough to do what I really want to do.” At least, barely.

She gestured toward her fledgling plants in this greenhouse, and the two as-yet-unfilled greenhouses beyond the windows. “I earned what I own here. I paid good money for it. I scrimped and saved and nickeled and dimed. For years I did what I had to do. Now, I’m doing what I want to do. Flowers are my passion.”

But for the occasional self-indulgence, like the vintage Chanel suit she wore today, she’d scraped by and had put the rest into savings and investment accounts.

Through the years, she’d even sewn her own clothes. Still did.

She shot him a look, uncertain whether the sound he’d just made was a snort or a clearing of his throat. Either way, she wasn’t so naive that she didn’t know judgment when she heard it. “There’s more to life than the bottom line. Money isn’t everything, Gray.”

“No? You’re a romantic, Audrey. Everyone needs something to live on.”

“True, but how much is necessary and how much overkill? Why is it no longer okay for businesses to believe that making millions is enough? Everyone wants to be the next computer geek gazillionaire, at any cost. People no longer matter, only more and more money. Insane, unreasonable amounts of money.”

“Is that what you see is wrong with the world these days?” She thought she detected a glint of admiration in his eyes. Or maybe not. His mouth had a cynical cast to it. Surprise, surprise. Their philosophies, after all, directly opposed each other.

“One of many things.”

She couldn’t fix the world, but she could control her small corner of it. “I want to spread joy with my flower arrangements. I want to spend the rest of my life doing something I enjoy. I can make this business work.”

He nodded, cataloguing that information, but why?

His fingers drummed against his thighs, as though nervous energy hummed through his body needing an escape. “Do you dress like that when you go on dates?”

Dates? “What does that have to do with anything?” She did, but it was none of his business. She’d had her share of boyfriends, most of them good men. She’d just never considered one a keeper. “My boyfriends have never complained about my clothes.”

Gray shrugged and looked at the plants. “Tell me about them,” he demanded.

She watched him and remained silent. The man had no authority over her.

“Please.” He’d softened his tone.

“Okay.”

The first row held her myriad weird and wonderful mushrooms.

“What is that?” he asked, indicating a hedgehog of a mushroom.

“Lion’s mane,” she answered.

“It looks like Cousin Itt,” he said, “but with shorter hair.”

The corner of Audrey’s mouth kicked up. She’d often thought so, too.

Gray stepped closer, using his body to make her uneasy. She was pretty sure his subtle intimidation was deliberate. Oh, please. As if that was going to work on her.

She had to be honest with herself. To a certain extent, it did. Where with every other man on the planet she was strong, Gray left her vulnerable. The woman in her liked the man in him too much, breaking down the barricades erected between them as business adversaries.

He unsettled her, the heat from his body penetrating the careful walls she constructed against him. He smelled clean and crisp and green, like her fields, like the forest after a rainfall.

Even though his cologne reminded her of an earthy forest floor, of evergreens, something else hovered around him, too. Cigarette smoke. Yuck. She would have sworn the boy she’d known, who’d loved nature and impish exploration, could never turn into a man this cold and be a smoker to boot.

Tall and fit, he loomed over her. Maybe she should be afraid, but she wasn’t. So many years ago, Gray had been her little buddy. He would never hurt her, but his heat so close to her right arm, and his sheer forceful presence, distracted her. Audrey forgot what she’d been about to say.

This close, she noticed things about him that gave her hope he might not be stronger than her, cracks in his perfect veneer, tightness in his jaw and a tension that radiated from him like static electricity.

He might want the world to believe he was in control, but something was bothering Gray, feeding his nervous system with darkness. She knew as surely as she recognized her own heartbeat that he was a deeply unhappy man.

About to open her mouth to ask, What happened to you, Gray? she felt his withdrawal, as though he sensed she saw too deeply.

He pretended a normalcy whose authenticity she questioned, and asked, “What are those?” He walked to the next row of plants.

She swallowed her concern. If he didn’t want to confide in her, there was nothing she could do.

“Rare orchids.” She held herself back from naming all of her orchids. Not everyone shared her enthusiasm.

Thelymitra ixioides, with its bright blue flowers that bloomed on warm, sunny days, waited patiently for her attention. She thought of telling him how hard it would be to get it to bloom indoors, but held her tongue, wary of this über-practical man and his motives, of his probable question, So why do it?

Whimsy. Pure utter whimsy that he would never understand.

She didn’t want to tell this cold stranger too much, didn’t want to disclose her hopes and dreams to a man who would use them against her.

“And those?” he asked, pointing to her baby sunflowers.

Despite herself, absurdly pleased that he showed interest, she disclosed the names of both her dwarf and her giant varieties. “Coming along nicely, my dears,” she whispered to them.

She showed off the miniature topiaries she was training into the shapes of small animals—a rabbit and two hedgehogs and a squirrel with a bushy tail.

She indicated her Clematis aureolin. “I’m growing this for the strange hairy seedpods it will get in the fall. If you thought lion’s mane looked like Cousin Itt, these will be little green baby Cousin Itt wannabes.”

He didn’t return her smile. Where his height and big body had failed to intimidate her, his cold, flat eyes did. If eyes were the windows to the soul, Gray’s eponymous ones had the shutters firmly closed against her. Or against everyone?

Where are you, Gray? Where did you retreat to all of those years ago when you left me alone?

The temperature in the room dropped, February in August, and the warmth of the day leached out of her.

This was not her friend, not the boy she’d run wild with over Turner fields when they were barely old enough to be out on their own. They’d trusted each other. They’d looked out for one another.

Audrey shivered. Gray wouldn’t watch out for her now. He was her enemy. He wanted to bring her down.

Amused by her discomfort, the corners of his lips twitched. “I don’t know much about flowers, but this is all really strange stuff. Peculiar. Not standard fare for a floral shop. Why are you growing it?”

Audrey’s glance flew to the poster she’d hung beside the door for inspiration, advertising the Annual Colorado State Floral Competition in Denver on the second Sunday in September. Gray turned to see what had snagged her attention.

He jerked his thumb toward the poster. “What’s this?”

She shrugged. She planned to win the trophy. She needed the $25,000 award desperately, and even more, the yearlong contract being offered to the winner to provide all of the arrangements in one of Denver’s boutique hotels, as well as the hospital’s gift shop. The future clients and prestige the win could bring would be huge for a fledgling business. Gray didn’t need to know that, though.

He stared at her and must have seen something on her face. Hope and determination, she guessed. She’d never been a great card player, had lost every hand of poker she’d ever played. He smiled, but not nicely, as though he had a secret, but one he didn’t intend to share with her.

She’d always believed that somewhere beneath that crisp, cool exterior the Gray Turner she had known must still exist. Oh, how wrong she’d been.

“You’re wrong, Audrey.”

Nonplussed, she stared. The man could read her mind?

Tapping a finger against the poster, his grin mocking her belief that, despite her quirkiness, she’d grown up to be a better person than the man he’d become, he said, “Money is everything.”

He left the greenhouse. Chilled, Audrey rushed down the aisles, touching her plants, drawing hope from their fledgling fight to survive, struggling to drive the chill from her blood.

Gray hadn’t returned because he was interested in her work. He’d needed to find where she was vulnerable, and he had.

Knowing his reputation as a hardheaded businessman, she knew he would use it against her, but she didn’t have a clue how. While she might be strong enough to fight the attraction she felt toward him and win, she knew she wasn’t a fraction of the businessperson he was.

She’d been a business owner for only nine months.

Her rib cage cradled her pounding heart as though it were a baby bird needing protection.

What if—?

Audrey, stop. Just stop. Gray’s playing games, messing with your head, but you don’t have to let him.

She left the greenhouse and locked it behind her, wishing she could coat the building in steel to protect her babies from the likes of Grayson Turner.

She strode to her car, morning dew moistening her feet through the peekaboo holes in the toes of her shoes. She glanced back over her shoulder. Sunlight glimmered from the many panes of her greenhouses, igniting shimmering golden jewels in the middle of emerald fields—and a fire in her to burst Gray’s arrogant bubble.

No, she didn’t have to buy into his intimidation tactics. She was strong.

CHAPTER TWO

AUDREY’S HEADY PERFUME followed Gray out the door, trailing him like a scarf that wrapped itself around his shoulders with comforting hands. Nuts.

Nothing about Audrey said comfort. Words that came to mind were sexy and strange and disconcerting, but comforting? Never.

The black eyeliner slanting up at the corners of her violet eyes made them exotic. In the middle of her pure, clear-skinned face, the effect was violently erotic.

Unnerved to feel anything good about the woman, he ordered himself to snap out of it.

She had the power to hurt his family, and he wouldn’t stand for it.

Babies. Gray laughed. She’d called her plants her “babies.” Nutbar. Defeating this woman was going to be a piece of cake.

At least in grilling Audrey, he’d calmed down enough to see his father without confrontation.

Gray drove to his parents’ home. At thirty-six, he shouldn’t be living with his mom and dad, but they were getting on in age, and he felt better being around in case something happened to one of them.

Set apart from town on its private cul-de-sac, the gray stone house with the white trim and black lacquered front door spoke of well-bred money, of discreet, respectful living.

He’d had a good upbringing. So why was he screwed up these days? Why so neurotic?

The garage door was open and Dad was inside. Good. There were things that needed to be said.

“Dad?” he called.

Dad had his head buried inside a deep box. “Aha!” He stood, triumph and a childlike joy lighting his face. “Here they are.”

“We need to talk—”

“Remember these?” He held an old snorkel set of Gray’s in his hands, the rubber of the ancient flippers dry and cracked.

“Yes, I remember. I must have been nine or ten when you bought them for me.” He didn’t have time for this. They had issues to settle. Huge issues.

Dad wore an old cardigan, ratty around the edges from years of use. White hair curled over the collar of the sweater. Disgraceful. Dad used to be particular about his grooming.

“What happened to you, Dad? Something’s changed.” The words were out of his mouth before good manners could stop them, a sign of how bad Gray’s nerves were. Dad’s aging, the slow crumbling of a once-powerful man, affected Gray, left him sad and a little lost. Left him somehow smaller, at a time when he was already vulnerable with residual grief. Marnie was dead.

Stop. Concentrate on the here and now, on business.

“I turned eighty last year.” For all of Gray’s recent worries about Dad’s state of mind, especially given the shaky business dealings lately, Dad had understood his question perfectly.

Gray waited for more explanation. When it didn’t come, he prompted, “And...?”

“And you try turning eighty and looking back on your life and realizing how much time you spent indoors in a stuffy old office when you could have been out doing things.” He pulled out a plastic oar belonging to an old dinghy that had been relegated to the dump years ago. “Look!” His chuckle held a strange glee that Gray had never heard before, not sinister, just, again, childlike.

Gray couldn’t get past his surprise. Dad had regrets? “But...”

“But what?”

“But you loved the business.”

“Past tense. I’m tired. I want to enjoy what’s left of my life. I want peace.”

How had Gray missed Dad’s transformation from a savvy businessman to a reluctant one? Gray had tried to visit as often as possible, but given that he’d taken after his father with twelve-hour days and a demanding, if loved, girlfriend, it had been hard. Obviously, he hadn’t come home often enough.

“You’re here now,” Dad asserted. “You take care of the business.”

Speaking of which...

“Did you sell a piece of land to Audrey Stone in the winter?”

“Jeff Stone’s daughter?” Dad looked up from the box he was still rummaging through. A fine fuzz of white stubble dusted his unshaven chin. Dad shaved every day. Apparently not today.

The gray eyes that Gray had inherited still seemed sharp, but his glance shifted away from Gray’s. What was he hiding? Over and over, Gray had had to find out things about the company from Hilary or the accountant. While Dad seemed to welcome Gray into the business, he also stonewalled him at too many turns. Something strange was up with his father.

He said he was tired. He said you take care of the business. His actions spoke a different language. Dad couldn’t let go of the reins.

“Yes,” Dad replied. “I sold land to Audrey. Why?”

“It’s in the heart of the land I want to sell to Farm-Green Industries.”

“Hmm. Too bad.”

Dad had become a master of understatement. Gray gritted his teeth. “Why did you sell?”

“Jeff is sick.”

“What does that have to do with the land?”

“His daughter needs to take care of him.”

Gray bore the frustration of dealing with Dad like this, but only barely. Conversation was like pulling freaking teeth out of his head one by one. Without anesthetic. Where was the man who used to be open about everything?

“Dad, what does that have to do with our land?”

“She needed a place to grow plants and flowers for her floral shop. She needs to support herself and help her father. We stopped using those greenhouses years ago. Shame to see them go to waste.”

“But we’ve spent months hammering out this deal with Farm-Green. They aren’t going to take it with a huge hunk of land missing from the middle.”

“I never wanted to sell to them anyway. When they first started sniffing around two or three years ago, I told you that.”

God, give me strength. “We’ve gone over this a hundred times. You need to look at the big picture. Look outside of Accord. The economy isn’t what it used to be. The whole country is suffering. The lumberyard isn’t bringing in a fraction of the money it used to. We need that money to pay your employees.” Let alone take care of all of the other dubious decisions Dad had made lately.

“So, find a different solution. Something else that will work. If one thing doesn’t, find another.”

“There won’t be another company who’ll pay what Farm-Green was willing to so quickly. It could take a year to find someone else who’s interested, and then months more of negotiations. I’m turning myself inside out to come up with creative solutions to our problems.”

Dad shrugged. “When one door closes, another opens.”

One of Dad’s empty pronouncements. He thought they were nuggets of wisdom. Not even close. New-age gobbledygook.

“Did you at least get a good price?” Gray wouldn’t put it past his father to give the land away for sentiment’s sake.

Judging by Dad’s annoyed frown, he’d asked the wrong question. “Of course I did. I spent sixty years working as a successful businessman.”

Yes, Gray knew that, but Dad had lost his grip on reality. He was eighty years old and changing, reverting to childhood, or something. He should have retired twenty years ago, but what would he have done instead? Retirement would probably have killed him, but in the past months that Gray had been home, he’d finally had to accept that Dad needed to step away from the business altogether before he sent the whole thing down the drain. Dad was still too sharp for this to be Alzheimer’s. This wasn’t a failing, wasn’t even dementia, just a change. But why?

“Isn’t Jeff Stone the one you pay a salary to even though he’s off work?”

“I pay him a reduced salary. An early retirement.”

“Even though he was short of fulfilling his requirements?”

“He’s going blind.” Gray flinched at Dad’s harsh tone. “Jeff worked for me for twenty-nine years. His macular degeneration precluded him from working his final year.”

“He would qualify for disability. Why make the company bear the financial burden of his care?”

“He would make a pittance on disability. He has medical bills. He needs an operation that will cost a fortune. He’s middle class, not a millionaire.” Dad pulled the second oar out of the box but threw it onto a growing rubbish heap when he discovered it was broken. “Paying Jeff is no burden. He worked hard for me and, by extension, since you enjoyed the secure childhood and higher education the business bought, for you. The least we can do is show our appreciation.”

Dad was too softhearted to run a successful company in today’s environment. Disability was designed for this situation, for people like Jeff.

Gray opened his mouth to argue further, but Dad forestalled him. “Selling those greenhouses to Audrey was the right thing to do. Give it some thought and you’ll agree.”

Before he said something too harsh, Gray left the garage. For sixty years, his dad had done everything right, but in the past year, it seemed he’d been getting it all wrong. Or maybe longer. The further Gray dug into records and finances, the more he realized that Dad had been making risky investments and dubious decisions for a while.

Also, he’d caught him lying more than once. No, that wasn’t fair. They weren’t lies, just convenient half-truths so that Gray had to double-check everything Dad told him to find the truth for himself.

His stomach burned.

Did Mom have antacid tablets in the house? He could use a couple. Or the whole bottle.

Inside, he found her sitting in the living room. Where Dad’s grooming was suffering with age, Mom still looked perfect.

Dressed to the nines even this early in the morning, she wore a silk blouse with a soft pastel print and a tweed skirt, her still slim legs encased in stockings and her feet in stylish black heels.

She sat on the sofa reading a romance novel. She had just turned seventy-five, for Pete’s sake. He didn’t need to catch her holding a book with a photograph of a half-naked man clutching a busty woman on the cover.

Even so, when she peeked at him over the rims of her reading glasses, her once-vivid blue eyes faded now, his heart swelled. A cloud of white hair framed a tiny face. Her welcoming smile warmed him. This amazing woman had given him everything, the absolute best childhood.

“Can I get you anything?” he asked, and he meant anything. For his parents, especially Mom, he would do whatever was asked of him. “A cup of tea?” Mom loved her tea.

“I’m fine,” she answered. “I’ve already had four cups this morning.”

“Mom,” he said, hesitating because he didn’t want to offend, but needing to know. “What’s happening with Dad?”

She didn’t seem surprised by the question. “He’s tired. He’s had a lot of weight on his shoulders for a long time. He needs to let go and relax.”

“He said it started when he turned eighty.”

She set her glasses down on top of her book. “Oh, it started well before that. He’s been tired for years.”

Startled, Gray asked, “Why didn’t he tell me? I would have come home sooner.”

Those faded blue eyes studied him shrewdly. “Would you have?”

His mind flew to an image of Marnie with her hands on her hips, obstinate in battle with him. “Yes,” he said, but he’d taken too long to answer.

“Truly?”

Gray slumped into the armchair. “I don’t know. Marnie didn’t want to live here. She loved Boston.”

“You would have had to have made a choice. Your parents or your fiancée. I understood that, Gray, so I didn’t tell you about your dad’s state.”

Gray leaned forward and rested his elbows on his knees. “Mom, I love you and Dad. I would have worked out something.”

“What could you have done? You loved Marnie, too, and Boston is not within commuting distance. Would you have lived six months here and the other half of the year there? Like a child in joint custody? What kind of life would that have been, especially once you had children?”

“I don’t know. I would have come up with a solution.”

Mom closed her book and put it on the side table, giving him her full attention. “Why did it take so long for you and Marnie to set a wedding date? You were engaged for five years.”