Полная версия

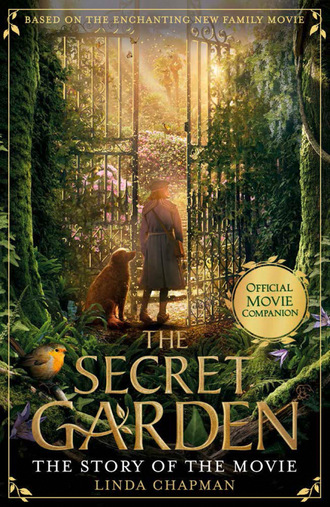

The Secret Garden: The Story of the Movie

Mary had no idea why the way she looked might upset her uncle, but, before she could ask, Mrs Medlock was already leading the way up the stone steps to the iron-bound, oak front door. Mary followed her into the huge entrance hall. Portraits of stern-looking ladies and men frowned down from the walls and a wide central staircase led up to a landing with a huge window. It couldn’t have been more unlike the bright, airy villa she had lived in in India.

‘First things first,’ said Mrs Medlock, marching over to a brass light switch on the wall. ‘We’re fully electric.’ She pulled the switch down. The huge glass chandelier in the centre of the hall lit up briefly, but then there was a fizzling sound and the lights went out again. Mrs Medlock raised her eyebrows. ‘But that doesn’t mean it always works. So, if you’re needing the facilities in the night, take a lamp. Secondly, the master is a widower and on his own. He has promised you will have someone to look after you soon enough, but in the meantime don’t you be expecting there’ll be people to talk to you because there won’t.’

Standing in the cavernous hall, Mary refused to be daunted. She lifted her chin. ‘I need no entertaining. I am not a child.’

She felt a stab of satisfaction as she saw the housekeeper blink in surprise. Mrs Medlock turned and led the way up the grand staircase. On the first landing the staircase split, heading off in opposite directions. Mary followed her down a long, gloomy corridor.

‘This house is six hundred years old,’ said Mrs Medlock as the corridor twisted and turned past endless closed doors. ‘There are near a hundred rooms. You’ll be told which ones you can go into and those you’re to keep out of, but until then you’re to stick to your rooms and your rooms only. Is that understood?’ Mary nodded. ‘You may play in the grounds outside, but no exploring the house.’ Mrs Medlock gave her a warning look. ‘No poking about.’

Mary met her gaze. ‘I assure you, Mrs Medlock, that I have no interest in “poking about”.’

‘Hmm,’ Mrs Medlock sniffed and stopped beside a door. ‘This is you,’ she said, opening a door to a bedroom. Mary went inside and Mrs Medlock quickly shut the door behind her. She heard the housekeeper walking away, her boots tapping on the floorboards.

Looking round the vast room, Mary felt very small. There was an iron bed with a thin cover and one thin pillow. Next to it was a bedside cabinet with a single lamp. The floor was just bare wooden boards with a couple of threadbare rugs, and the walls were covered with fading wallpaper painted with trees and birds. There was a huge window with long, heavy curtains on either side, a small fire burning in the grate, and an old rocking horse and a battered toy chest.

So this is my new bedroom, Mary thought, looking round at the shabby, old-fashioned things. No, I will not cry, she thought fiercely as she felt her throat tighten. She wondered about her uncle. She had thought she would be introduced to him when she arrived, but maybe he didn’t want to see her. Mrs Medlock’s words had certainly given her the impression that he hadn’t wanted her to come to Misselthwaite.

No one wants me, she thought, her heart swelling with a desperate loneliness. No one likes me. Everyone probably wishes I had died in India.

She took off her boots and coat and got under the thin embroidered coverlet of the bed, drawing her knees up to her chest. She thought of India – the sunshine, the bright red and yellow orchids that bloomed after the rain, the monkeys in the trees, the ripe mangoes; Daddy swinging her round in his arms and calling her his little monkey; her ayah smiling fondly at her, happy to bring the little Miss Sahib whatever she wanted.

I want to go back, Mary thought longingly. To my home, to the sunshine and the flowers. I want to wake up and see Daddy and Ayah and for this all to be a terrible nightmare.

A little voice piped up inside her. But it isn’t a nightmare. It’s real and it all happened because of the wish you made …

No! She didn’t want to think about that.

Staring hard at the embroidered flowers on the coverlet, Mary made herself imagine they were real flowers, vibrant and sweet-smelling. As her imagination began to work its magic, they seemed to brighten and grow in front of her eyes, moving, bending, sweeping her far, far away …

Mary was back in her garden in India. It was part dream, part memory from a year ago. She ran towards the palm tree, her legs pounding. She’d climbed it the day before. For the first time, she’d got up it by herself and now she wanted her mother to see. She wanted her to be proud of her! Glancing back at the villa, she saw her mother walking along the veranda, one hand on her forehead, her head bowed.

‘Mother! Look, I’m climbing!’ Mary shouted, starting to climb up. Higher and higher she went. ‘Mother? Look, please!’ Her voice rose as she glanced round, hoping her mother had seen her triumphant climb. But her mother was walking back into the house. She hadn’t even glanced in Mary’s direction …

Mary woke up in the dark, feeling unhappy and cold. Her eyes darted around. Where was she? As she spotted the shadowy rocking horse and the enormous stone window, it all came back to her. Of course. She was at Misselthwaite Manor. Someone had been into her room, taken away her coat and boots and shut the curtains while she’d been asleep – Mrs Medlock maybe or a maid?

Mary shivered, wanting more blankets. In India she had always had a bell by her bed and, whenever she had rung it, her ayah had appeared. But here there was no bell. ‘Hello?’ she tried calling. She raised her voice. ‘Hello?’ But her words just rang out in the eerie silence.

A high wail from somewhere in the house made her jump. It sounded like a child, but there were no other children here in the manor house. Was it a bird or an animal maybe? Mary heard the noise again. Swinging her legs out of bed, she padded inquisitively to the bedroom door. The sound seemed to be coming from a floor above the one she was on. Perhaps it was her uncle. She listened, head on one side. It didn’t sound like a grown man. A worrying thought struck her. Could … could it be a ghost?

A shiver passed over her skin and for a moment Mary wondered if she should just stay in her room and ignore it. But her curiosity got the better of her. She had to find out what was making such a dreadful noise.

Gathering her courage, she left her room and set off along the gloomy corridor.

The House at Night

No one replied and so she continued up the dark, twisty staircase. The wails started again and then stopped. Quickening her pace, Mary reached a landing lit by a shaft of moonlight filtering in through a window at the end. She hurried along the dark, narrow corridor and turned the corner.

There was a ghost! Mary stopped with a gasp as she saw a girl standing at the far end of the corridor. It took her a few seconds to realise that she was looking at an enormous mirror and the phantom girl was just her own reflection. She let out a relieved breath and felt her racing heart start to slow down.

There was a sudden noisy clatter overhead and Mary’s nerve failed her. Turning, she sprinted back along the corridor as if a whole army of phantoms were after her. She dived into her bedroom and slammed the door shut, leaning against it and gasping for breath. As her breathing calmed, she hurried to her bed and, pulling the coverlet over her head, she shut her eyes. She didn’t open them again until morning.

When Mary woke next, she saw that light was shining round the edges of the heavy curtains. Had her night-time adventure really happened?

Getting out of bed, she pulled open the curtains and saw that her room looked out on to the sweeping driveway and, beyond the driveway, out on to the misty moors. As Mary watched, a man came out of the house, dragging an old iron bedframe behind him. He flung it on to the gravel. He was about as old as her father and was wearing dark trousers and a waistcoat over a shirt with rolled-up sleeves. His face was craggy and sad, etched with deep wrinkles, and his hair was messy.

That must be my uncle, Mary thought.

There was something odd about him. It was his back, she realised. He had a hump on his shoulders that made him bend over slightly at the waist. Mrs Medlock’s strange words – don’t you go staring at him – suddenly made sense. Mary peered down with interest, wondering why no one had ever told her that her uncle was a hunchback. She wouldn’t have minded. She had once read a story about a man with a crooked back who had married a beautiful princess whom he had loved very much.

He hurried back into the house and reappeared a minute later, dragging another bed. This time Mrs Medlock was with him.

‘Sir!’ she exclaimed. ‘Please leave the beds. The army will come and collect them. You don’t need to do this.’

‘It needs sorting out,’ he said stubbornly.

‘I know but not like this. You’ll do yourself an injury. Please, sir, come back inside.’ Mrs Medlock gave him a pleading look. Mary saw her uncle run a hand through his hair and then give in. As he started to follow Mrs Medlock back into the house, he glanced up towards Mary’s window. Mary ducked down, not wanting him to see she had been spying on him. She retreated back into her room, thinking about the lines etched in her uncle’s face. He wasn’t very old, but he looked like someone who had suffered.

Just then, the bedroom door opened and a maid came in. She was neatly dressed in a grey dress buttoned up to the neck and looked about twenty. Her thick dark hair was tied back tidily in a low bun and she was carrying a tray with a bowl of porridge on it.

Mary wondered why the maid hadn’t knocked before entering. ‘Who are you?’

‘What’s that for a greeting?’ said the maid with a smile.

Mary blinked at her impudence.

‘You’ll call me Martha. You’re Mary, I hear,’ the maid went on. Putting the tray down, she went over to the fireplace.

Mary stared at her. She was used to Indian servants who never spoke unless they were spoken to. They would answer her if she asked a question, but otherwise they bowed and stayed silent.

Martha began to rake out the cinders. ‘There’s a fine chill in the air today, isn’t there?’ she went on chattily as she spread paper on top of the ash. ‘But spring is on its way. That’s what my brother Dickon says. He’s always out on the moors and knows more about nature and animals than anyone.’

Mary frowned. She wasn’t sure she liked this talkative servant. ‘I was cold in the night,’ she said accusingly. ‘No one heard when I called.’

‘I’m guessing that’s because we were all in our beds too,’ the maid said. ‘There’s a second blanket under your bed if you’re cold tonight.’

‘And I heard noises too,’ Mary went on. ‘Wailing, screaming.’

‘No,’ Martha said firmly, adding a layer of coal to the fire. ‘You heard the wind, that’s all. It blows right bad around the house.’

Mary considered this. Maybe Martha was right and she’d got scared over nothing. Not wanting to seem foolish, she changed the subject.

‘Well, I needed someone. You should sleep outside my room. My ayah did and she would always come if I called her.’

To her astonishment, Martha just raised her eyebrows. ‘Well, whoever Ayah is, she’s sure as not here, is she?’ she said, lighting the fire. ‘And I won’t be sleeping outside your room tonight or any other night. I’ll be sleeping in my own bed, thank you very much.’

‘But aren’t you going to be my servant?’ said Mary, surprised.

‘Your servant?’ Martha’s smile widened. ‘No, girl. I’m just here to check the fire’s lit, the room’s shipshape and you’ve food in you. Nothing more. I’ve got countless other jobs to do around the house. Now eat your porridge. It’s getting cold.’

Mary inspected the porridge. It was lumpy and had a skin forming on top of it. She didn’t like the look of it all. ‘I don’t eat porridge,’ she informed Martha, lifting her chin. ‘For my breakfast, I like bacon and eggs.’ She waited for Martha to take the tray away and fetch her something else, but Martha just grinned.

‘I like them too but you’ve got porridge. Now come on, time to get yourself dressed,’ Martha said, opening the wardrobe. Mary saw it was filled with clothes for her. Martha handed her a dress, some undergarments, stockings and a cardigan.

‘You want me to dress myself?’ said Mary, astounded. ‘But aren’t you going to do that?’ Her ayah had always dressed her.

‘Dress you?’ echoed Martha. ‘Whatever for? You’ve got hands and arms, haven’t you?’ She shook her head. ‘Goodness, Mother always said she couldn’t see why grand people’s children didn’t turn out to be fools. What with needing help with washing and dressing and being took out to walk as if they were puppies.’ She chuckled. ‘I see what she means now.’

Mary’s temper snapped. How dare this rude maid laugh at her! With an angry exclamation, she stamped her foot, her fists scrunching up at her sides.

Martha took a startled step backwards. For a moment, there was a long pause, then she shook her head. ‘And to think I was excited to have a young’un in the house,’ she said ruefully as she turned and left the room.

Mary stared after her. Martha had seemed hurt. I don’t understand, Mary thought. She rubbed her forehead. Things were so different in England.

She looked at the clothes in her arms. If children dressed themselves in England, then that’s what she would do. She certainly didn’t want to give that maid a chance to laugh at her any more. Chin jutting with determination, she managed to get undressed, pulled on the vest and bloomers and the woollen stockings. Then she put the dress over the top. It was an old-fashioned pinafore style, loose fitting with long sleeves and a hem that reached her knees, but Mary didn’t care. Clothes were clothes and at least this dress was easy to put on.

When she was dressed, she took a few mouthfuls of porridge. It was cold and claggy now and she began to wish she’d eaten some of it when it was still warm. She looked round the room. What should she do? Her eyes fell on the large rocking horse.

It was old but beautiful. It had a leather saddle and bridle and a dapple-grey coat. Its dark eyes were large and its mane and tail – made from real horsehair – were long and thick. Its legs were positioned as if it was moving. Wondering who it had belonged to, Mary scrambled on to its back. Holding the reins, she started to make it rock backwards and forwards, slowly at first, but getting higher every time and, as she did so, she shut her eyes and her imagination that had been lying dormant, like a bulb in the winter soil, suddenly put out a green shoot. For a few precious, fleeting minutes, she forgot everything she hated about her new life and let her imagination transport her away. She wasn’t Mary Lennox – the orphan from India whom no one wanted or liked – she was beautiful Sita, escaping from an evil demon, carried by a winged horse across the bright blue Indian sky …

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.