Полная версия

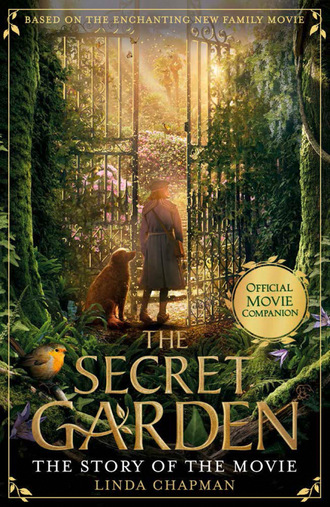

The Secret Garden: The Story of the Movie

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Children’s Books in 2020

Published in this ebook edition in 2020

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd,

HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

The HarperCollins Children’s Books website address is

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Written by Linda Chapman

Based on the screenplay by Jack Thorne,

and based on the original novel by Frances Hodgson Burnett

© 2020 STUDIOCANAL S.A.S., All rights reserved.

Cover design copyright © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2020

All rights reserved.

Linda Chapman asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of the work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook onscreen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008340070

Ebook Edition © March 2020 ISBN: 9780008340087

Version: 2020-02-04

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Chapter One: Noises in the Night

Chapter Two: A Long Journey

Chapter Three: Misselthwaite Manor

Chapter Four: The House at Night

Chapter Five: Exploring Misselthwaite

Chapter Six: Making Friends

Chapter Seven: Colin

Chapter Eight: Mr Craven

Chapter Nine: The Secret Garden

Chapter Ten: Cousins

Chapter Eleven: Dreams and Memories

Chapter Twelve: Dickon

Chapter Thirteen: The Hidden Room

Chapter Fourteen: The Robin’s Secret

Chapter Fifteen: Taking Risks

Chapter Sixteen: New Friends

Chapter Seventeen: Caught

Chapter Eighteen: Prisoner

Chapter Nineteen: Unlocking the Past

Chapter Twenty: A Way Out

Chapter Twenty-One: The Fire

Chapter Twenty-Two: Believe in Magic

Chapter Twenty-Three: Four Months Later …

About the Publisher

Noises in the Night

‘Jemima, can you sleep?’ she whispered. Jemima stared back at her.

Mary liked to pretend that Jemima could understand everything she said because talking to Jemima and telling her stories helped Mary feel less lonely and bored. She didn’t have any brothers or sisters, and the servants – apart from her ayah, her Indian nanny – kept their distance. She wasn’t allowed to play outside much because the sun was very strong. Her father was too busy with his work to play games with her as much as she’d like and her mother … Mary chewed her lower lip. She knew her mother didn’t like her. At times, Mary even suspected that she hated her.

Well, I hate her too, Mary thought, scowling.

There was a scream from somewhere in the villa and then the sound of a crash and a door slamming. A wisp of fear curled in Mary’s tummy as she glanced at her bedroom door. What was going on?

She’d heard her father talking to his friends about how there was a lot of fighting in India at the moment. Mary didn’t really understand, but it sounded like the Indian people didn’t want the English to be in India any more and wanted them to leave. Daddy and his friends had talked about fighting in the streets. But surely those streets were a long way away, in distant cities. The Indian servants who worked for the Lennox family did whatever they were told so Mary couldn’t imagine them fighting. No, she was safe here. Nothing bad would happen to her.

Trying not to listen to the muffled bangs and crashes and shouts from outside her room, she stroked Jemima’s woollen hair. ‘Are you scared, Jemima?’ she whispered. ‘Well, don’t be. It’s just grown-ups being grown-ups. Shall I tell you a story to make you feel better?’

Lighting a lantern, she got out of bed and took Jemima to a den she had made out of cushions and throws in the middle of her room. She began to recite one of her favourite stories, using shadow puppets to act it out as she spoke. It was a story her ayah had told her about a boy called Rama and a girl called Sita who loved each other, but then one day a demon kidnapped Sita and took her away. Ayah’s stories were always filled with gods and demons, magic and excitement.

By the time Mary was nearing the end, the noises outside had quietened down, and her eyelids were starting to feel heavy. ‘Rama was just about to catch up with Sita and the demon, but then the demon threw down fire and imprisoned him in flames,’ she said, yawning. ‘Luckily, the fire god, Agni, was watching and he parted the flames and carried Rama up into the clouds. After that, the two of them set off, looking – ever looking – for Rama’s love,’ she finished.

Blowing out the lantern, she sank back on the cushions with Jemima in her arms. Her eyelashes fluttered and a few seconds later she was asleep.

A damp green lawn … flowerbeds filled with pink, lilac and blue flowers … trees with branches bursting with blossom … Mary ran down a path past statues … A grown-up was holding her hand. She was laughing, trying not to fall over, and she felt happy, wonderfully and completely happy …

Slowly, Mary began to wake up. For a moment, she tried to hold on to the familiar dream, but it faded just like it always did. The dream garden looked so different to any garden she had ever known, but it seemed so real to her when she was there and she always felt truly happy in it. With a sigh, she rubbed her eyes. The first thing she noticed was that the shutters were still open and it was very bright outside. Sunlight was flooding in through the window. Mary’s tummy rumbled. Where was her ayah? Why hadn’t she brought her breakfast?

Feeling hungry and cross, she sat up in her den. ‘Ayah!’ she called loudly. To her surprise, the door didn’t open to reveal her ayah’s kindly face. Feeling even crosser, Mary raised her voice. ‘Ayah! I’m calling you! It’s late and I’m not even dressed!’ Her voice reached shouting pitch. ‘AYAH!’

Mary waited. Still no one came. What was going on? The house was very quiet. That was peculiar, she realised. Usually, she could hear the servants bustling around. Unease flickered through her as she remembered the strange noises in the night.

‘Should … should we go and look around and see if we can find anyone, Jemima?’ She tried to sound brave but her voice trembled slightly. ‘Yes, I think that’s a very good idea,’ she went on. ‘Don’t worry. I’ll look after you. We’ll go and find Daddy and he shall get Ayah for us.’

Opening the door of her bedroom, she paused. The corridor outside her room was in chaos. Pictures had been pulled from the walls and were now lying on the floor without their gold frames. Heart beating fast, she started to hurry through the villa. Every room was the same – curtains had been torn down, ornaments lay smashed on the floor, much of the furniture had disappeared and, in the kitchen, the cupboards were open and the shelves bare. Everything of any value had vanished and, worst of all, there was no one there at all.

‘Father? Daddy? Ayah?’ Mary’s voice rose anxiously. She pushed the doors to the veranda open. The sun shone down brightly, but the garden was as deserted as the house. Mary clutched Jemima.

‘Where have they all gone?’ she whispered.

A Long Journey

No one had come to the house for two days until two English officers turned up. They had been astonished to find her there – dirty, thirsty, hungry – and had taken her to the hospital. She had asked them where her father and mother were, but they had just told her to be a good girl and not to worry. At the hospital, a nurse gave her something to eat and drink, and helped Mary bathe and change into clean clothes. Then Mary was seen by a doctor. Neither the nurse nor the doctor would answer her questions about her parents either.

As she waited in a small room, wondering when Daddy was going to come and take her home and what he would say when he found out that all the servants had vanished, she heard the two officers talking in a room next door.

‘This is a frightful mess,’ said one gravely. ‘Poor child. If only we had evacuated the family before the trouble broke out. The cholera epidemic couldn’t have come at a worse time for them.’

Mary pricked her ears. She knew that cholera was a disease that killed lots of people, but what did it have to do with her family?

‘The doctor tells me her mother was struck down with cholera very suddenly. Her father rushed her here in the night, but it was too late,’ the first officer continued.

Mary froze, foreboding running down her spine. Too late for what?

‘The mother died that night and then the father died the next morning.’

Mary’s heart started to pound so fast she thought it was going to burst out of her chest. Mother and Daddy … both dead? She drew in a sharp breath. No, they couldn’t be dead. They couldn’t be! But even as the thought formed she knew, with a horrible, crashing certainty, that it must be true. The officers wouldn’t make a mistake about something like that. A sob ripped up through her, half whimper, half choking cry.

There was the sound of feet and one of the officers looked in through the door. ‘Oh, Lord. She’s here.’ He cleared his throat awkwardly, clearly having no idea how to comfort a ten-year-old girl.

His companion joined him. ‘What in heaven’s name are we going to do with her? She can’t stay here,’ he said.

Mary looked up through her tears to see the first officer consulting his notes.

‘She has a widowed uncle in England,’ he said. ‘We’ll send her back on the boat with the other children.’

From then on, Mary was passed around like an unwanted parcel. On leaving the hospital, she was sent to stay with a clergyman called Mr Crawford who had a wife and five children of his own. She heard the adults around her saying it would be better for her to be with other children, but she didn’t understand why. She didn’t want to play with the Crawford children. They were younger than her and they wanted to know all about her parents and how they had died. She felt miserable and wouldn’t answer their questions. Finally, she lost her temper, ripping up a drawing that the youngest had done for her and screaming at them all to leave her alone. After that, they stayed away from her, watching her as if she was a strange, wild animal. Mary didn’t care. She didn’t feel like she would care about anything ever again.

She had heard the clergyman and his stout, well-meaning wife talking about her in whispers: ‘Poor child … Word has been sent to England … He’s her uncle by marriage, you know … He was married to her mother’s twin sister who died years ago … Such a tragedy, poor man … but he’s her only living relative … He’ll have to take her, whether he likes it or not …’

Finally, a telegram had arrived. ‘The ship that will take you to England leaves tomorrow,’ Mrs Crawford informed Mary. ‘Your uncle – Mr Craven – who was married to your Aunt Grace, has agreed to take you in. He lives in Yorkshire at a place called Misselthwaite Manor. You’re a lucky girl, Mary. Your uncle is a rich man.’

Mary swallowed. How could Mrs Crawford possibly say she was lucky? Her parents were dead and she was going to live with some old uncle in a horrible house in a strange country! Tears pricked her eyes, but she wouldn’t cry in front of the Crawfords – she wouldn’t!

Pressing her lips tightly together, she nodded and then walked up the stairs. Reaching her bedroom, she shut the door behind her and then threw herself down on the bed, sobbing into the pillow to muffle her bitter tears.

The ship that carried Mary from Bombay to England was crowded and noisy. There were many families on board, all returning to England because of the unrest in India. Mary had to eat with the other children and do what she was told. She hated it – the food was horrible and the other children were rough and loud. On the first day, she had pushed her plate of food away. ‘This is disgusting!’ she said.

A scruffy boy sitting next to her grabbed her plate and emptied the food on to his own plate.

Mary stared at him, outraged. ‘I didn’t say you could do that!’

‘You didn’t say I couldn’t,’ the boy replied. ‘If you aren’t going to eat it, I am.’

‘You don’t understand,’ Mary exclaimed. ‘I need better food than this. My parents are dead.’

He shrugged. ‘We’ve all lost, girl.’

Mary watched as he gobbled up her food. She didn’t like him much, but he was the only person who had spoken to her so far. ‘Would … would you like to hear a story?’ she asked tentatively.

He gave her a scornful look. ‘No, I’m not a child.’ He got up and moved away to sit by someone else, leaving Mary on her own. Since then, she had barely spoken a word to anyone.

Standing up, Mary now walked to the side of the ship. A railing ran round the deck and the deep blue ocean swelled below. She lifted up Jemima. Maybe she could tell her one of Ayah’s tales and escape into it, forgetting everything else. Telling stories had always been her way of coping when Mother didn’t want to see her or when Daddy was too busy to play.

‘I’ll tell you a story, Jemima,’ she said. ‘Just like I used to do at home. There once was a Lord of the Seas. His name was Varuna and he … and he …’

The words seemed to dry up in her head. She tried again. ‘Varuna was very powerful. He …’ She faltered. But it was no use. All Mary could think about was home.

‘I don’t have a home, do I, Jemima?’ she whispered. ‘I don’t belong anywhere or to anyone now.’

Mary felt a sudden stab of pain as she looked into Jemima’s blank face. Jemima was just a doll, not a friend. Only children played with dolls and children had to eat what they were given and keep quiet. Children were passed from place to place; children had to do what grown-ups wanted. She suddenly made up her mind.

‘I’m not a child,’ she said fiercely. ‘Not any more.’

She let Jemima go. As the doll hit the water far below, shock filled Mary. What had she just done? Jemima floated on the surface for a moment. She stared up at Mary one last time and then the waves dragged her under.

A lump swelled painfully in Mary’s throat, but she swallowed it back. No more tears, she told herself. She lifted her chin, her eyes defiant. She wasn’t going to cry again – not now, not ever.

Crossing her arms, she turned away from the railings, a lock snapping shut on her broken heart.

Misselthwaite Manor

Mary was reminded of a word her father had once used to describe the elderly aunt of a colleague. Formidable, he had called her. Yes, formidable is just what Mrs Medlock is, thought Mary. But she reminded herself that Mrs Medlock was just the housekeeper – a servant – and so had to do what the family told her to do.

Remembering her decision not to be a child any more, Mary met Mrs Medlock’s gaze. ‘Very well,’ she said coldly.

Head held high, Mary followed Mrs Medlock to the train that was to take them to Yorkshire. As the whistle went and it started to puff along the rails, clouds of steam shooting out from its funnel, Mary became aware that Mrs Medlock was studying her.

‘Well, you’re a plain little piece of goods, aren’t you?’ Mrs Medlock said in her Yorkshire accent.

Mary puzzled over the words, trying to work out what they meant. I think it’s her way of saying I’m not very pretty, she decided. Mary didn’t mind the comment because she didn’t consider herself particularly pretty either. She didn’t have the long golden hair of a princess in a storybook or the jet-black hair and enchanting brown eyes of the Indian girls in her ayah’s tales. She was small and skinny with hair the colour of a conker. Her skin was pale, her inquisitive hazel eyes almost too large for her face. Her words are true, Mary thought, but what a strange thing for a servant to say.

She turned and stared out of the window.

Opposite her, Mrs Medlock settled herself more firmly in her seat. ‘Now I don’t know what you’ve been told, girl,’ she began with a warning note in her voice, ‘but don’t be expecting luxury at Misselthwaite. It’s not the house it was.’

Her eyes grew distant and for a moment Mary had a feeling she was reliving the past.

‘When the young mistress was alive, there was a full household staff, a stable of horses, grand balls, but that’s all changed now.’ She tutted indignantly. ‘Those army savages! They turned the house into a hospital during the war. Brought the wounded, the dead and the dying. They set up camp in the garden and kept their sick in the ballroom. Quite took over the place and now there’s no knowing what to do with the house. They left it a wreck!’

Mary didn’t say anything.

Mrs Medlock clearly expected more of a response. ‘Well? Don’t you even care?’

‘Does it matter whether I care or not?’ said Mary bluntly.

Mrs Medlock’s eyes narrowed. She gazed at her for a long moment. ‘Well, you are an odd duck, aren’t you?’

Mary’s initial dislike of the housekeeper intensified and she turned to look out of the window again, not wanting to talk to her any more. Mrs Medlock sniffed and got out a book to read.

As the train headed north, Mary continued to gaze out. England was so grey! Rain slanted against the train window. Sodden fields stretched in all directions, cows and sheep hanging their heads in the downpour. It was so different from the bright sunshine of India. There the rain was as welcomed as a longed-for guest, making flowers burst into life and fresh green buds push their way up through the parched soil.

On and on the train went until they pulled into a station and transferred to a car driven by an unsmiling, gruff man. As they drove away from the station, Mary fell asleep. When she woke up, she saw an endless expanse of grey on either side of the car. She had never seen anything like it. ‘Is that the sea?’ she asked as she looked at the clouds swirling across the top.

‘The sea! What a foolish thing to say, girl. Out there are the moors,’ snorted Mrs Medlock. ‘Be sure to stay inside when the mist is rolling or you may not find your way home.’

From her tone of voice, it sounded as if she didn’t think that would be a bad thing. Mary’s lips tightened. She had the strong feeling that Mrs Medlock didn’t want her at Misselthwaite any more than she wanted to be there. Well, she can stay out of my way and I’ll stay out of hers, she thought fiercely. All I want is to be left alone.

They drove on and on along the narrow strip of road that cut across the moors, past heather, sheep and wild ponies. Occasionally, through the shroud of mist, Mary thought she saw the glow of orange and red flames flickering weakly and once she was sure she caught sight of a group of raggedly dressed people trudging beside a pony and cart, but, as she looked more closely, the mist closed in and the shadowy figures vanished from sight.

It seemed as if the journey would never end, but finally they turned down a long drive. Parkland stretched away on either side until it merged with the moors. At the end of the drive was an enormous stone manor house with sharp turrets silhouetted against the twilight sky. A single weak light shone out of an upstairs window.

‘There it is,’ Mrs Medlock announced with a touch of pride in her voice as she looked at the dark, forbidding fortress of a house. ‘Misselthwaite.’

As the car swept through the gates, Mary noticed a robin perched on one of the pillars. For a moment, it seemed to look straight at Mary and then it flew away.

The car stopped. Mary gazed up at the vast house and felt a shiver run through her. It looked like the kind of place where ghosts and phantoms walked at night.

‘This is your home now,’ said Mrs Medlock. ‘Thanks to your uncle’s kindness.’ She fixed Mary with a stern look. ‘Now, when you see him, you’re not to stare, girl. Do you understand?’

Mary was puzzled. Why ever did Mrs Medlock think she would stare at her uncle?

Mrs Medlock went on. ‘He’s suffered enough, poor man. And now to see you, looking the way you do … No.’ She shook her head as if that would be too much. ‘A shadow, that’s what you’ll have to be at Misselthwaite, girl. Just a shadow.’