Полная версия

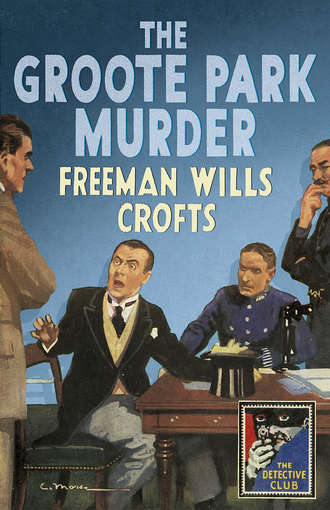

The Groote Park Murder

But, interesting as was this find, it offered no aid to identification, and Clarke turned with some eagerness to the pocketbook and papers.

The latter turned out to be letters. Two were addressed to Mr Albert Smith, c/o Messrs. Hope Bros., 120-130 Mees Street, Middeldorp, and the third to the same gentleman at 25 Rotterdam Road. Sergeant Clarke knew Hope Bros. establishment, a large provision store in the centre of the town, and he assumed that Mr Smith must have been an employee, the Rotterdam Road address being his residence. If so, his problem, or part of it at all events, seemed to be solved.

As a matter of routine he glanced through the letters. The two addressed to the store were about provision business matters, the other was a memorandum containing a number of figures apparently relating to betting transactions.

Though Sergeant Clarke was satisfied he already had sufficient information to lead to the deceased’s identification, he went on in his stolid, routine way to complete his inquiry. Laying aside the letters, he picked up the pocketbook. It was marked with the same name, Albert Smith, and contained a roll of notes value six pounds, some of Messrs. Hope Bros. trade cards with ‘Mr A. Smith’ in small type on the lower left-hand corner, and a few miscellaneous papers, none of which seemed of interest.

The contents of the pockets done with, he turned his attention to the clothes themselves, noting the manufacturers or sellers of the various articles. None of the garments were marked except the coat, which bore a tab inside the breast pocket with the tailor’s printed address, and the name ‘A. Smith’ and a date of some six months earlier, written in ink.

His immediate investigation finished, Sergeant Clarke returned to Dr Bakker in the other room.

‘Man’s name is Albert Smith, sir,’ he said. ‘Seems to have worked in Hope Bros. store in Mees Street. Have you nearly done, sir?’

Dr Bakker, who was writing, threw down his pen.

‘Just finished, Sergeant.’

He collected some sheets of paper and passed them to the other. ‘This will be all you want, I fancy.’

‘Thank you, sir. You’ve lost no time.’

‘No, I want to get away as soon as possible.’

‘Well, just a moment, please, until I look over this.’

The manuscript was in the official form and read:

‘11th November.

‘To the Chief Constable of Middeldorp.

‘SIR,—I beg to report that this morning at 6.25 a.m. I was called by Sergeant Clarke to examine a body which had just been found on the railway near the north end of the Dartie Avenue Tunnel. I find as follows:

‘The body is that of a man of about thirty-five, 6 feet 0 inches in height, broad and strongly built, and with considerable muscular development. (Here followed some measurements and technical details.) As far as discernable without an autopsy, the man was in perfect health. The cause of death was shock produced by the following injuries: (Here followed a list.) All of these are consistent with the theory that he was struck by the cowcatcher of a railway engine in rapid motion.

‘I am of the opinion the man had been dead from eight to ten hours when found.

‘I am, etc.,

‘PIETER BAKKER.’

‘Thank you, Doctor, there’s not much doubt about that part of it.’ Clarke put the sheets carefully away in his pocket. ‘But I should like to know what took the man there. It’s a rum time for anyone to be walking along the line. Looks a bit like suicide to me. What do you say, sir?’

‘Not improbable.’ The doctor rose and took his hat. ‘But you’ll easily find out. You will let me know about the inquest?’

‘Of course, sir. As soon as it’s arranged.’

The stationmaster had evidently been watching the door, for hardly had Dr Bakker passed out of earshot when he appeared, eager for information.

‘Well, Sergeant,’ he queried, ‘have you been able to identify him yet?’

‘I have, Stationmaster,’ the officer replied, a trifle pompously. ‘His name is Albert Smith, and he was connected with Hope Bros. store in Mees Street.’

The stationmaster whistled.

‘Mr Smith of Hope Bros.!’ he repeated. ‘You don’t say! Why, I knew him well. He was often down here about accounts for carriage and claims. A fine upstanding man he was too, and always very civil spoken. This is a terrible business, Sergeant.’

The sergeant nodded, a trifle impatiently. But the stationmaster was curious, and went on:

‘I’ve been thinking it over, Sergeant, and the thing I should like to know is,’ he lowered his voice impressively, ‘what was he doing there?’

‘Well,’ said Clarke, ‘what would you say yourself?’

The stationmaster shook his head.

‘I don’t like it,’ he declared. ‘I don’t like it at all. That there piece of line doesn’t lead to anywhere Mr Smith should want to go to—not at that time of night anyhow. It looks bad. It looks to me’—again he sank his voice—‘like suicide.’

‘Like enough,’ Clarke admitted coldly. ‘Look here, I want to go right on down to Mees Street. The body can wait here, I take it? One of my men will be in charge.’

‘Oh, certainly.’ The stationmaster became cool also. ‘That room is not wanted at present.’

‘What about those engines?’ went on Clarke. ‘Have you been able to find marks on any of them?’

‘I was coming to that.’ Importance crept once more into the stationmaster’s manner. ‘I had a further search made, with satisfactory results. Traces of blood were found on the cowcatcher of No. 1317. She worked in the mail, that’s the one that arrived at 11.10 p.m. So it was then it happened.’

This agreed with the medical evidence, Clarke thought, as he drew out his book and made the usual note. Having made a further entry to the effect that the stationmaster estimated the speed of this train at about thirty-five miles an hour when passing through the tunnel, Clarke asked for the use of the telephone, and reported his discoveries to headquarters. Then he left for the Mees Street store, while, started by the stationmaster, the news of Albert Smith’s tragic end spread like wildfire.

Messrs. Hope Bros. establishment was a large building occupying a whole block at an important street crossing. It seemed to exude prosperity, as the aroma of freshly ground coffee exuded from its open doors. Elaborately carved ashlar masonry clothed it without, and within it was a maze of marble, oxidised silver and plate glass. Passing through one of its many pairs of swing doors, Clarke addressed himself to an attendant.

‘Is your manager in yet? I should like to see him, please.’

‘I think Mr Crawley is in,’ the young man returned. ‘Anyway, he won’t be long. Will you come this way?’

Mr Crawley, it appeared, was not available, but his assistant, Mr Hurst, would see the visitor if he would come to the manager’s office. He proved to be a thin-faced, aquiline-featured young man, with an alert, eager manner.

‘Good morning, Sergeant,’ he said, his keen eyes glancing comprehensively over the other. ‘Sit down, won’t you. And what can I do for you?’

‘I’m afraid, sir,’ Clarke answered as he took the chair indicated, ‘that I am bringing you bad news. You had a Mr Albert Smith in your service?’

‘Yes, what of him?’

‘Was he a tall man of about thirty-five, broad and strongly built, and wearing brown tweed clothes?’

‘That’s the man.’

‘He has met with an accident. I’m sorry to tell you he is dead.’

The assistant manager stared.

‘Dead!’ he repeated blankly, a look of amazement passing over his face. ‘Why, I was talking to him only last night! I can hardly believe it. When did it occur, and how?’

‘He was run over on the railway in the tunnel under Dartie Avenue about eleven o’clock last night.’

‘Good heavens!’

There was no mistaking the concern in the assistant manager’s voice, and he listened with deep interest while Clarke told him the details he had learned.

‘Poor fellow!’ he observed, when the recital was ended. ‘That was cruelly hard luck. I am sorry for your news, Sergeant.’

‘No doubt, sir.’ Clarke paused, then went on, ‘I wanted to ask you if you could tell me anything of his family. I gathered he lived in Rotterdam Road? Is he married, do you know?’

‘No, he had rooms there. I never heard him mention his family. I’m afraid I can’t help you about that, and I don’t know anyone else who could.’

‘Is that so, sir? He wasn’t a native then?’

‘No. He came to us’—Mr Hurst took a card from an index in a drawer of the desk—‘almost exactly six years ago. He gave his age then as twenty-six, which would make him thirty-two now. He called here looking for clerical work, and as we were short of a clerk at the time, Mr Crawley gave him a start. He did fairly well, and gradually advanced until he was second in his department. He was a very clever chap, ingenious and, indeed, I might say, brilliant. But, unfortunately, he was lazy, or rather he would only work at what interested him for the moment. He did well enough to hold a second’s job, but he was too erratic to get charge.’

‘What about his habits? Did he drink or gamble?’

Mr Hurst hesitated slightly.

‘I have heard rumours that he gambled, but I don’t know anything personally. I can’t say I ever saw him seriously the worse for drink.’

‘I suppose you know nothing about his history before he joined you?’

‘Nothing. I formed the opinion that he was English, and had come out with some stain on his reputation, but of that I am not certain. Anyway, we didn’t mind if he had had a break in the Old Country, so long as he made good with us.’

‘I think, sir, you said you saw Mr Smith last night. At what hour?’

‘Just before quitting time. About half past five.’

‘And he seemed in his usual health and spirits.’

‘Absolutely.’

Sergeant Clarke had begun to ask another question when the telephone on the manager’s desk rang sharply. Hurst answered.

‘Yes,’ he said. ‘Yes, the assistant manager speaking. Yes, he’s here now. I’ll ask him to speak.’ He turned to his visitor. ‘Police headquarters wants to speak to you.’

Clarke took the receiver.

‘That you, Clarke?’ came in a voice he recognised as that of his immediate superior, Inspector Vandam. ‘What are you doing?’

The sergeant told him.

‘Well,’ went on the voice, ‘you might drop it and return here at once. I want to see you.’

‘I’m wanted back at headquarters, sir,’ Clarke explained as he replaced the receiver. ‘I have to thank you for your information.’

‘If you want anything more from me, come back.’

‘I will.’

On reaching headquarters, Clarke found Inspector Vandam closeted with the Chief in the latter’s room. He was asked for a detailed report of what he had learned, which he gave as briefly as he could.

‘It looks suspicious right enough,’ said the great man after he had finished. ‘I think, Vandam, you had better look into the thing yourself. If you find it’s all right you can drop it.’ He turned to Clarke with that kindliness which made him the idol of his subordinates. ‘We’ve had some news, Clarke. Mr Segboer, the curator of the Groote Park, has just telephoned to say that one of his men has discovered that a potting shed behind the range of glass-houses and beside the railway has been entered during the night. Judging from his account, some rather curious operations must have been carried on by the intruders, but the point of immediate interest is that he found under a bench a small engagement book with the name Albert Smith on the flyleaf.’

Clarke stared.

‘Good gracious, sir,’ he ejaculated, ‘but that’s extraordinary!’ Then, after a pause, he went on, ‘So that’s what he was crossing the railway for.’

‘What do you mean?’ the Chief asked sharply.

‘Why, sir, he was killed at ten minutes past eleven, and it must have been when he was leaving the park. Across the railway would be a natural enough way for him to go, for the gates would be shut. They close at eleven. There are different places where he could get off the railway to go into the town.’

The Chief and Vandam exchanged glances.

‘Quite possibly Clarke is right,’ the former said slowly. ‘All the same, Vandam, I think you should look into it. Let me know the result.’

The Chief turned back to his papers, and Inspector Vandam and Sergeant Clarke left the room. Though none of the three knew it, Vandam had at that moment embarked on the solution of one of the most baffling mysteries that had ever tormented the brains of an unhappy detective, and the issue of the case was profoundly to affect his whole future career, as well as the careers of a number of other persons at that time quite unknown to him.

CHAPTER II

THE POTTING SHED

OF all the attractions of the city of Middeldorp, that of which the inhabitants are most justly proud is the Groote Park. It lies to the west of the town, in the area between city and suburb. Its eastern end penetrates like a wedge almost to the business quarter, from which it is separated by the railway. On its outer or western side is a residential area of tree-lined avenues of detached villas, each standing, exclusive, within its own well-kept grounds. Here dwell the élite of the district.

The park itself is roughly pear-shaped in plan, with the stalk towards the centre of the town. In a clearing in the wide end is a bandstand, and there in the evenings and on holidays the citizens hold decorous festival, to the brazen strains of the civic band. Beneath the trees surrounding are hundreds of little marble-topped tables, each with its attendant pair of folding galvanised iron chairs, and behind the tables in the farther depths of the trees are refreshment kiosks, arranged like supplies parked behind a bivouacked army. Electric arc lamps hang among the branches, and the place on balmy summer evenings after dusk has fallen is alive with movement and colour from the crowds seeking relaxation after the heat and stress of the day.

The narrow end nearest the centre of the city is given over to horticulture. It boasts one of the finest ranges of glass-houses in South Africa, a rock garden, a Dutch garden, an English garden, as well as a pond with the rustic bridges, swans and water lilies, without which no ornamental water is complete.

The range of glass-houses runs parallel to the railway and about fifty feet from its boundary wall. Between the two, and screened from observation at the ends by plantations of evergreen shrubs, lies what might be called the working portion of the garden—tool sheds, potting sheds, depots of manure, leaf mould and the like. It was to this area that Inspector Vandam and Sergeant Clarke bent their steps when they left headquarters.

Waiting for them at the end of the glass-houses were two men, one an old gentleman of patriarchal appearance, with a long white beard and semitic features, the other younger and evidently a labourer. As the police officers approached, the old gentleman hailed Vandam.

‘’Morning, Inspector,’ he called in a thin, high-pitched voice. ‘You weren’t long coming round. I hope we have not brought you on a fool’s errand. As I told your people, I would not have troubled you at all only for the name in the book being the same as that of the poor gentleman who was killed. It seemed such a curious coincidence that I thought you ought to know.’

‘Quite right, Mr Segboer,’ Vandam returned. ‘We are much obliged to you, sir.’

The curator turned to his companion.

‘This is Hoskins, one of our gardeners,’ he explained. ‘It was he who found the book. If you are ready, let us go to the shed.’

The four men passed round the end of the glass-houses and followed a path which led behind the belt of evergreen shrubs to the building in question. It was a small place, about eight feet by ten only, built close up to the boundary, in fact, the boundary wall, raised a few feet for the purpose, formed one of its sides. The other three walls were of brick, supporting a lean-to roof of reddish brown tiles. There was no window, light being obtained only from the door. The shed contained a rough bench along one wall, a few tools and flowerpots, and a bag or two of artificial manure. The place was very secluded, being hidden from the gardens by the glass-houses and the evergreen shrubs.

‘Now, Hoskins,’ Mr Segboer directed, as the little party stopped on the threshold, ‘explain to Inspector Vandam what you found.’

‘This morning about seven o’clock I had to come to this here shed for to get a line and trowel for some plants as I was bedding out,’ explained the gardener, whose tongue betrayed the fact of his Cockney origin, ‘and when I looked in at the door I saw just at once that somebody had been in through the night, or since five o’clock yesterday evening anyhow. The floor seemed someway different, and then, after looking a while, I saw that it had been swept clean, and then mould sprinkled over it again. You can see that for yourselves if you look.’

The floor was of concrete, brought to a smooth surface, though dark coloured from the earth which had evidently lain on it. This earth had certainly been brushed away from the centre, and was heaped up for a width of some eighteen inches round the walls. A space of about seven feet by five had thus been cleared, and the marks of the brush were visible round the edges. But the space had been partly re-covered by what seemed to be handfuls of earth, and here and there round the walls it looked as if the brush had been used for scattering back some of the swept-up material.

Vandam turned to the man.

‘You say this was done since five o’clock last night,’ he said. ‘Were you here at that time?’

‘Yes, I left in the line and trowel when I quit work last night.’

‘And what was the floor like then?’

‘Like it always was before. There was leaf mould and sand and loam on it; just a little, you know, that had fallen from the bench. But it was all over it.’

‘You found something else?’

The man pointed to the corner opposite the bench.

‘Them there ashes were not there before.’

In the corner was a little heap of burnt paper, and now that the idea was suggested to Vandam, he believed he could detect the smell of fire. Still standing outside the door, he nodded slowly and went on:

‘Anything else?’

‘Ay, there was the pocketbook. When I was coming out with the line and trowel, I saw something sticking out of a heap of sand just there. I picked it up and found it was a pocketbook, and when I looked in the front of it I saw the name was Albert Smith. I wondered who had been in the shed, for I didn’t know anyone of that name, and I slipped the book into my pocket, saying to myself as how I’d give it to the boss here first time I saw him. Well, then, after a while I heard that a man called Albert Smith had been found dead on the railway just back of the wall here, so I thinks to myself there’s maybe something more in it than what meets the eye, and I had better give the book to the boss at once, and so I did.’

‘And here it is,’ Mr Segboer added, taking a small notebook bound in brown leather from his pocket and handing it to Vandam.

There was no question of the identity of the owner, for the same address—that of Messrs. Hope Bros. of Mees Street—followed the name on the flyleaf. The book was printed in diary form, each two pages showing a week. Vandam glanced quickly over it. The notes seemed either engagements, or reminders about provision business. There was nothing in the space for the previous evening.

Vandam questioned the gardener closely on his statement, but without gaining additional details. Mr Segboer could give no helpful information, and Vandam dismissed both after thanking them and, more by force of habit than of deliberate purpose, warning them not to repeat what they had told him.

To Inspector Vandam the circumstances were far from clear. From what he had just learned, it seemed reasonable to conclude that Smith had visited the shed some time between five and eleven on the previous evening, probably near eleven, as the sergeant’s suggestion that he had been killed while leaving the Park after the gates were closed was likely enough. But was there not, at least, a suggestion of something more? Did the visit to the shed not mean an interview with someone, a secret meeting, and, therefore, possibly for some shady purpose. For a secret interview probably no better place could have been found in the whole of Middeldorp. If it were approached and quitted by the railway after dark, as it might have been in this instance, the chances of discovery would be infinitesimal. What could Smith have been doing there?

At first Vandam thought of a mere vulgar intrigue, that he was meeting some girl with whom he did not wish to be seen. But the sweeping of the floor seemed to indicate some more definite purpose. What ever could it have been?

It was fairly clear, Vandam imagined, that the scattering of the earth over the floor was done to remove the traces of its having been swept. If so, it had been badly done and it had failed in its object. Was this, he wondered, due to lack of care, or to haste, or to working in the dark?

He could not answer any of these questions, but the more he thought over them, the more likely he thought it that Smith had been engaged with another or others in some secret and perhaps sinister business.

Inspector Vandam was mildly intrigued by the whole affair, but it did not seem of passing importance. He decided that after taking a general look round, he would return to headquarters and consult his Chief as to whether the matter should be further followed up. He therefore turned from the shed to its immediate surroundings.

At the end of the shed, between the path and the boundary wall, the ground was covered with low heaps of leaf mould. The stuff had evidently lain there for a considerable time, for the surface had grown smooth, almost like soil. Across this smooth surface and close to the end of the shed passed two lines of footsteps, one coming and the other going.

Vandam stood looking at the marks. They were vague and blurred and quite useless as prints, and yet there was something peculiar about them. At first he had assumed—without reason, as he now realised—that they were Smith’s tracks approaching and leaving the shed. But now he saw they had been made by different persons. Those receding were closer together and much deeper than the others, and he began to picture a tall, thin man arriving, and a short, stout one going away.

And there he would probably have left it, had not Sergeant Clarke at that moment walked across the leaf-mould to look over the wall. Almost subconsciously Vandam noticed that his steps made comparatively little impression, about the same, indeed, as those of his hypothetic thin man. But Clarke was not thin. He was a big man, tall, broad and well developed.

‘I say, Clarke,’ Vandam looked up suddenly, ‘what do you weigh?’

‘Just turn the scale at sixteen stone,’ returned the other stolidly, no trace of surprise at the question showing on his wooden countenance.

‘I thought so,’ Vandam muttered, turning his eyes again on the footprints. Somewhat puzzled, he walked across the strip himself, and turned to see what marks he had made. Vandam was a small man, thin though wiry, and his weight, he knew, was just under twelve stone. The prints he had left were considerably lighter than Clarke’s.

At first he wondered whether atmospheric conditions might not have rendered the leaf-mould softer on the previous night than it was now, but he immediately realised that no such change in the weather had taken place. No, there seemed to be no way of escaping the obvious suggestion. The man who had left the gardens had been carrying a heavy weight.

And this, if true, would account for the outward-bound prints being closer together than the others, so that they might well have been made by the same man. What could Smith have been carrying?

Vandam turned and looked over the wall. Below him was the railway cutting, and his eyes followed the curving line of rails until about fifty yards to the right it disappeared into the black mouth of the Dartie Avenue tunnel. From where he stood, it was just possible to see the place where the body had lain, and Clarke lost no time in pointing it out.