Полная версия

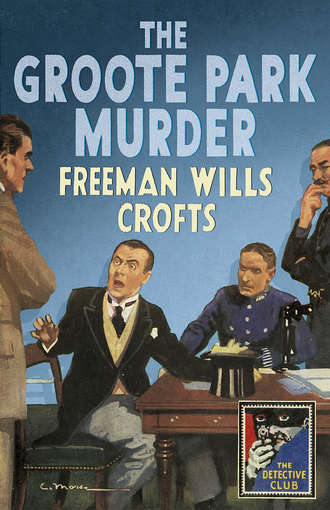

The Groote Park Murder

Vandam recollected that the medical evidence was not inconsistent with such a supposition. Dr Bakker had examined the body between seven and eight on the Thursday morning, and had given it as his opinion that death had taken place about ten hours previously. The Inspector was aware that such testimony was not conclusive, but so far as it went, it supported the idea.

That evening, when he had finished his day’s work and was sitting smoking in his most comfortable armchair, Vandam’s thoughts returned to the case. What, he wondered, had taken place in that terrible shed in the Groote Park? What was the sequence of events which had led up to the tragedy? Was Swayne really the murderer? Had his quarrel with Smith been about the pretty barmaid, Jane Louden? Though at the moment he could not reply to these questions, he swore to himself that it would not be long before he learned their answers.

Presently he began to consider details. How had the victim been lured to his doom? By an anonymous letter? Or by one forged in Miss Louden’s handwriting? Vandam’s experience suggested something of the kind.

He tried to picture the happening at the shed, Smith’s arrival, his feeling his way in through the enshrouding darkness of the night, perhaps his whispered ‘Are you there?’ the dull thud of the sandbag on the unsuspecting head, the collapse of that powerful frame into a shapeless heap …

Vandam, reconstructing the scene, saw suddenly the significance of the sweeping of the floor and of the newspapers. Smith could not be allowed to fall on the earthy floor. Still less could Swayne roll the body over as he searched the pockets for the document which in all probability had been used to lure the victim to his doom. Why not? Simply because the clothes would be stained by earth, stained a different colour from the railway ballast, and would therefore afford a clue to the sharp-eyed detective who would be called in if any suspicion about the ‘accident’ arose. To lay newspapers on the floor would be an obvious precaution. But newspapers, covering an area on which was spread little heaps of earth and small stones, would tear when pressure came on them. Therefore the heaps of earth and the stones must be removed. The floor must be swept. And when the work of the newspapers was done, when the clothes had been searched and the document removed, and the body dragged down to where the accident was to be staged, these marks left in the shed must be removed. The papers must vanish. And how could this be done more efficiently than by burning? Vandam saw that Swayne would have to burn them. And he would have to throw back the earth over the floor so as to remove the signs of the sweeping.

Smoking feverishly, Vandam believed he could picture the whole scene: Swayne crouching, sandbag in hand and with murder in his heart, behind the door of the shed; Smith, possibly suspecting a trap, but still forced to go on, groping his way cautiously to the place; his sudden instinctive realisation of danger; the dull thud of the sandbag; the limp form falling; the dragging of it in so that the door might be shut and a light used; the search for a possible incriminating document; the extinction of the light, and the terrible, staggering journey with the corpse from that awful shed, across the wall and down on to the railway below. Vandam seemed to see it all; the dragging of the body into the tunnel; the leaving it across the rails; the return to the shed; the burning of the papers and the scattering of the earth; the stealthy crossing of the railway; the hiding of the sandbag cover and the hammer. The hammer! Vandam was brought up sharp in his imaginings. The hammer did not fit in. What had the hammer been used for?

Here was a problem on which at first light seemed unattainable. The Inspector rose to his feet and began silently pacing the room. For twenty minutes he strode up and down, his head bent forward, his lips moving as he put his thoughts into words, and then at last the sought for idea flashed into his mind. Was the hammer not a precautionary measure? Had it not been brought to the site, and used, because there was an element of doubt about the efficacy of the sandbag? A sandbag left no marks. How was Swayne, a layman without medical knowledge, in the imperfect light of the shed and in his hurry and excitement, to be quite sure that the sandbag had done its work? He must run no risk of his victim being merely stunned. He must be certain that there would be no revival in that body before the train came.

The more Vandam thought over it, the better his theory seemed to work in. He now saw why the sandbag had been used in the first instance. There must be no blood in the shed. And blood must not stain the murderer’s clothes as he dragged the body to the railway. But the railway once reached, he could complete his ghastly work. Blood on the line did not matter; it would be expected.

As Vandam thought over his theory, he felt distinctly pleased with himself. Starting from nothing, he had evolved a complete conception of what might have occurred, from the original motive almost down to the last detail. Of such an achievement he might be justly proud.

But he was under no illusions on the matter. He fully recognised that his idea was a mere guess, and he quite saw that some new fact might upset the whole of it and leave him as far from a solution as ever. However, his theory was at least something to go on, and he decided that his next step must be to test it. On the following day he would continue the tracing of Swayne’s movements on the fatal Wednesday night between the hours of 8.10 and 11.

CHAPTER V

ROBBERY UNDER ARMS

ONE of the things which added piquancy to Inspector Vandam’s life was the fact that at no time could he say with any reasonable degree of certainty where he would be or how he would be engaged an hour later. However he might plan, whatever arrangements he might make, he was for ever at the beck and call of the unexpected. His friends knew from experience that it was best to expect him when they saw him, and they were usually more surprised when he kept his appointments than when he broke them.

This attribute of his calling was exemplified when he reached headquarters on the following morning. He had arrived, his mind filled with the importance of finding out where Swayne was between eight and ten on the night of the murder. Fifteen seconds later Swayne was forgotten, and his thoughts were concentrated on a quite different side of his case. The event which produced this sudden change of outlook was nothing more nor less than the fact that he was informed that a Miss Jane Louden was impatiently awaiting the officer who was dealing with the matter of the accident to Albert Smith.

‘Show her to my room,’ Vandam said, and he looked up with eager interest as a tall, strongly-built girl entered.

She was dark, and her face was of a heavy and immobile type, though it was not without a certain coarse beauty. Her features were set in an expression of arrogance and scorn. After what he had heard of her, Vandam was at first surprised that she was not better looking. But before he was five minutes in her presence he became aware of a certain attraction which to some types of mind, he believed, might easily become irresistible. She was dressed quietly but extremely well in a dark blue coat and skirt, of which even Vandam could not but admire the cut, a small hat, silk stockings and patent shoes. She seemed as eager and excited as Vandam imagined it was her nature to be. He took her measure rapidly and bowed politely.

‘Good morning, Miss Louden,’ he said. ‘Won’t you sit down? I am Inspector Vandam, and I have been detailed to make inquiries into the death of the late Mr Albert Smith. I take it from your message you wish to see me?’

‘That’s so,’ the girl answered. She spoke quietly, but there was more than a suggestion of anxiety in her manner. ‘I felt I should come to headquarters the moment I heard of his death, but I just couldn’t lift my head at the time. I was down with ’flu, and I came just the moment I could stand. I’m not very well yet.’

‘I hope you’ll soon be all right,’ Vandam returned sympathetically. ‘In the meantime if there is anything I can do for you, I hope you will just let me know.’

‘That’s what I came for,’ she declared. ‘I can tell you in two words. It is not generally known that Mr Smith and I were engaged to be married, but that is the fact.’

Vandam did not see exactly where this was leading, but he made sounds of respectful commiseration and waited for more.

‘It was only five days ago, certainly,’ the girl went on, ‘and it wasn’t announced, but it was quite a definite engagement for all that. I wanted it kept quiet for a day or two. A girl does, you know. But I’m sorry I did now, though, of course, I couldn’t tell he would be fool enough to get run over. It puts me in an awkward position, right enough.’

Still Vandam did not see what was coming.

‘But who would question the fact of your engagement?’ he asked.

‘Nobody,’ she said grimly. ‘I’d like to see anyone trying it on. But I thought it would be only right that you people knew.’

‘Ah, quite so. Of course. No doubt,’ Vandam admitted. ‘We’ll certainly keep it in mind.’

But this evidently would not meet the case, and she proceeded to explain more definitely.

‘I suppose there’s no question I’ll be all right?’ she queried. ‘I don’t suppose he made a will—it would be just like him not to bother—but there can be no doubt of his intention.’

Illumination came over Vandam. Though a wide experience had made him tolerant of the frailties of human nature, he was unable to keep a slight feeling of disgust out of his mind as he looked at her. She could not show even a decent pretence at regret for the man who had loved her!

‘What about his relations?’ he asked, to see what she would say.

‘He hadn’t any.’ She spoke with a covetous eagerness. ‘I made quite sure of that. There is nobody but me that could have any claim at all. That is, in justice. But I was afraid that perhaps if there wasn’t an actual will in writing, that there might be some legal difficulty; that maybe I would only get a part.’

Vandam would have enjoyed telling her that she hadn’t the slightest chance of getting a farthing. But that would not be business. He must pump her well first.

‘I would hardly like to say off-hand,’ he said slowly. ‘These lawyers, you know; when once they get started …’ He shook his head to indicate the futility and meddlesomeness of the profession. ‘It would be a matter, I think, of evidence; what evidence there was of the engagement, whether there really were no relatives, and how far the engagement, if admitted, could be held to take the place of a formal will. I don’t know that I should like to say how it would go.’

‘Do you mean that?’ she cried, and there was now no doubt of the genuineness of her emotion. ‘But I tell you the stuff is mine! He said so. He said it was for me. Why, it was only on account of it that I promised to marry him. I tell you it was a bargain.’

‘Forty-five pounds of assets and a hundred of debts,’ thought Vandam. ‘What is she getting at?’ But aloud he said, ‘You speak as if the deceased gentleman had large means. I was not aware that that was so. His salary, I understand, was about £400, and of course that will die with him.’

‘Salary!’ she repeated scornfully. ‘It’s not his miserable salary I’m talking about. It’s the diamonds I want.’

Vandam automatically controlled a start of surprise, but a moment’s thought convinced him that he would gain nothing by pretending a knowledge of her meaning.

‘What diamonds are you speaking of?’ he therefore asked.

She stared at him.

‘Why—’ she burst out. Then a look of absolute horror dawning in her eyes, she sprang to her feet and screamed at him. ‘You don’t mean to say you don’t know? You don’t mean they weren’t on the body? Speak, can’t you?’

‘Sit down and control yourself,’ Vandam said sternly. ‘There was nothing of any value found on the body.’

She took no notice of his admonition, but stood glaring at him, crying with a torrent of bitter oaths that her diamonds had been stolen.

Vandam got up, seized her by the arm, and forced her into her chair.

‘Sit down there,’ he ordered harshly, ‘and don’t be more of a fool than you can help. If you talk calmly I’ll listen to you; otherwise you can get out of here and look for your diamonds yourself.’

The threat had some effect, and the girl stopped shouting.

‘Now,’ went on Vandam, ‘begin at the beginning and explain what you’re talking about. And remember you can’t do any monkeying with the police force. We’ve a quick way here of dealing with anyone that gives trouble.’

Somewhat cowed, the girl glanced at him venomously and began to speak.

‘It’s all very well for you,’ she grumbled sullenly. ‘You’ve lost nothing. It’s I that have had the loss, and you tell me to keep quiet.’

Vandam, convinced that he was on the eve of some important revelation, was awaiting her statement with keen interest, but all he said was, ‘If you don’t want our help, you needn’t wait.’

‘No,’ she said hurriedly. ‘I’ll tell you. Five days ago we were engaged. It’s true we didn’t—’

‘That’s no good,’ Vandam interrupted roughly. ‘You must tell me the whole thing. Begin at the beginning. How did you first get to know Mr Smith?’

‘It was about six months ago,’ she answered, and as she continued to speak she grew calmer and more coherent. ‘He came one night to the hotel—my father keeps a hotel in East Hawkins Street, you know. He was looking for a man who was staying there, a Mr—I forget his name—Jones, I think. Well, anyway, he found him, and they had some drinks in the bar. I served them, and they got talking to me part of the time. After that Albert began to come regularly, but it was a week or more before I knew he was after me. He got more and more friendly, and then one Saturday night he begged me to go for a walk with him next day. I didn’t do it then, but after he’d asked me three or four times I went. We went out on Sundays regularly after that, and then he asked me to marry him. I had found out about him by that time, and I knew he had little more than the clothes he stood in, so I told him the truth. I hadn’t any use for a poor man. He wouldn’t take No for an answer, and implored me not to shut down our acquaintanceship. I said if he was fool enough to hang round me on those terms I didn’t mind. Every now and then he’d ask me to marry him, but I wasn’t having any. He might have known I had made up my mind.’

She was talking now in what was presumably her natural manner, with a dull, heavy cynicism that made no attempt to cloak her selfishness and heartlessness. But, repulsive as she seemed to him, Vandam could imagine her possessing enormous influence over any man who might be unlucky enough to fall in love with her.

‘Two days before his death,’ she went on, ‘that was, on last Monday, he came into the bar, and I could see at once that something was up. He was all nervous and upset and was bubbling over with some news. He asked me to go out with him, saying he had something very important to tell me. I confess I was curious, so I agreed and we went to the Groote Park. When we had got away from the crowd, he said that at last he could ask me to marry him with a better heart. He had had a stroke of luck and would now be able to offer me a suitable home and income.

‘I asked what had happened, and he drew me over near one of the big lamps in the park and took something from his pocket.

‘“Look at that,” he said, and he showed me what I thought was a pebble at first, but what I saw then was a diamond. It was a medium-sized stone, not cut. I didn’t think much of it.

‘“What’s the use of that?” I asked him. “That’s not worth anything to make a song about.”

‘“Isn’t it though?” he said. “It’s worth a tidy £250, and perhaps £300.”

‘I was annoyed at that, for what was two or three hundred pounds to marry on? I was beginning to tell him what I thought of him when he stopped me.

‘“Ah,” he said, “but that’s not all. That’s one stone—it’s all I cared to carry on me—but there are more hidden away where that came from. There’s a bag in a safe place with forty-seven other stones, and most of them more valuable than this one.”

‘Well, that pretty well took away my breath. Ten or fifteen thousand pounds! That was talking.

‘“If you have that, I’ll marry you tomorrow,” I told him. He wanted to kiss me, but I wouldn’t let him. “No,” I said, “time enough for that sort of thing later. Wait ’til we’re married. I’ll see the money first.”

‘That sort of made him wild to sell the stones, but after a time I got him quieted down to tell me some particulars about them, and the more he told me, the more I began to believe in them.’

‘Did he tell you how he got them?’ Vandam interrupted.

‘Yes, that was the first thing I asked him. He said gambling. He said he was in a private room in one of the downtown houses, and there was high play going on and a lot of drinking. There were some men in from the mines, and they were staking stones on the play. Albert joined in. He had a run of luck and began to win their stones. He stood drinks again and again, and they were knocked over soonest, for they were half drunk when he went in, but he was as sober as you are. The stakes got higher and higher and the men drunker and drunker, ’til some of them could go on no longer and dropped out and went to sleep. But there was one big man that wouldn’t give way, and he staked and staked and lost to Albert every time. At last when they must all have been pretty mad, the end came. The big man staked all he had, a bag of twenty-one stones against Albert’s winnings. Albert by this time had twenty-seven stones in his bag. Albert won this time and collared the lot. Of course, they’d never have let him away alive; the big man pulled a gun on him at once, but Albert had seen the electric switch was just behind him as they sat at the table, and he nipped up and had the light off and was out of the place before they could get him. There was the devil’s own row and they fired all round, but he got clear away with the whole forty-eight.’

‘Where did this take place?’

‘He wouldn’t say and I didn’t bother to press him; somewhere down east, I gathered. He said it was the greatest piece of luck, for he hadn’t gone to the place intending to play. But he was in a rare old stew about it too; said if any of the miners got sight of him they’d have his life for sure. I told him to buy a gun, and he promised he would.’

This, then, was the explanation of the automatic pistol found on Smith’s body. Vandam had hoped for great things from the tracing of the weapon, but now it looked as if it would teach him nothing. ‘A promising clue gone west,’ he thought regretfully as he asked Miss Louden to continue.

‘We talked on about the thing, and I told him uncut diamonds were no use to me, and asked him what about getting them turned into cash. He said he’d thought of that, and that he was going to sell them quietly to one of the dealers; Messrs. Goldstein, he mentioned. He said he would go round to old Goldstein the next evening and see if he could fix up a satisfactory price. He didn’t want the deal to be known of, for he expected the men that had lost the stones to him would be watching the ordinary buyers, and might find him in that way. He came back on Tuesday night to say he had seen Goldstein, who had seemed willing to treat. Albert was to meet him with the stones the next night, that is, the night he was killed, to fix up the sale. I suppose he was going to the meeting place by the railway so as to avoid meeting people with all that wealth on him, and like the fool he always was he let himself get run over. I would have come and told you all about it this next morning only I had gone down with this darned ’flu, and I didn’t know ’til last night what had happened.’

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.