Полная версия

Treasury of Norse Mythology: Stories of Intrigue, Trickery, Love, and Revenge

Center of the Cosmos

An ash tree stands in a field.

The center of the Norse cosmos was an ash tree named Yggdrasil, a legend that may have its origin in the Arctic Sami people. They build a house with hide stretched across poles. So, a tree was the center of the home. That Yggdrasil was an ash tree makes sense. Ash resists splitting, so it makes good bows and tool handles. It’s springy, so it makes good mountain-walking sticks. It burns well, even when freshly cut. And it’s very hard, so it doesn’t wear out quickly.

And there were many corpses to feed on, for humans were more fragile than gods. On the third and lowest level of the cosmos was the realm of the dead. It took nine days to ride northward and downward from Midgard to get there. It was the deep and frozen northern land of Niflheim. A hateful monster presided there, all pink down to her hips and then greenish black and decayed from hip to toes, with a huge, bloody-muzzled dog, Garm, baying at her side. She went by the name Hel, and many called her realm by her name. In those days, to die was to go to Hel.

Beyond these six worlds, there were three more, whose locations are murky, as is that of Vanaheim. Fire giants dwelled in the smoky landscape Muspell. Dwarfs had the mountain caves in the land called Nidavellir. Near them was Svartalfheim, the land of the dark elves. They were crabby, mysterious beings, as different from the light elves as the moon is from the sun.

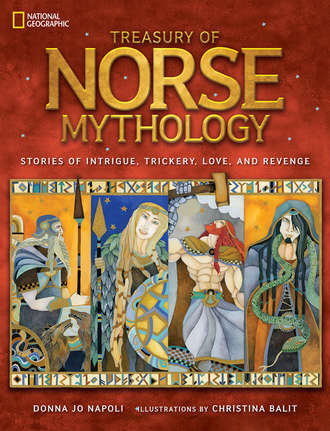

Rising up through the center of it all was a mighty ash tree called Yggdrasil. Its branches shaded all the nine worlds, and it dripped a sugary dew that swarms of bees made honey from—the very first honeydew. Three gigantic roots held it up, one that went through low Niflheim, one that went through Jotunheim on the middle level, and one that went through the highest land, Asgard. Gnawing at the cold root in Niflheim was the dragon Nidhogg. The squirrel known as Ratatosk ran up and down Yggdrasil, carrying words of envy and insult between the dragon below and the eagle that circled its talons around the tree’s limbs. Four stags leaped through the highest boughs, nibbling at the leaves. And a goat called Heidrun chewed on its tender shoots. Yggdrasil groaned in agony, yet stood tall with nobility. It was the noblest of trees. It looked out over everything, and the knowledge of the worlds seeped into it.

The ash tree Yggdrasil rose in the middle level of the cosmos, but it stretched its roots down to the bottom level and its branches up into the top level, making a whole that would stand strong only so long as the tree stood strong.

All the animals romping and feeding on Yggdrasil seem ordinary except for the dragon Nidhogg. Serpentine dragons slither through the Norse myths, embodiments of the lurking dangers of the natural world.

With all this abuse, surely the magnificent tree would have withered but for the efforts of three Norns. Norns were giantesses who ruled the destinies of humans. There were many of them, some malevolent, some beneficent. They were the ones responsible for one man’s son dying of illness and another’s surviving that same illness, for one woman perishing in her first childbirth and another producing a dozen offspring and still planting and plowing with strength. They were present at the birth of every child and no one could escape the fate they assigned. Whenever anything strange happened, anything weird, everyone knew it was the work of the Norns. Three of these Norns, lovely maidens all, took to caring for Yggdrasil. One was Urd—Fate. One was Verdandi—Being. One was Skuld—Necessity. They watered Yggdrasil daily with the purest water from the sacred spring of destiny, and they whitened the bark with clay from that very spring, to make it shine as clean and new as the lining of an eggshell and to protect it from rot and decay.

Three special Norns tended Yggdrasil. They gave the tree water from a sacred spring and coated its bark with that spring’s clay to keep it from decaying with age.

Yggdrasil served every kind of creature in every world of the cosmos. This most central tree made a whole of the cosmos, and so it was the most sacred place of all. Everyone knew that when Yggdrasil finally would shake, everyone would curl in fear, for the end of everything as we know it would be at hand. Indeed, that may be why the hideous dragon Nidhogg tormented the tree—to put an end to what otherwise would be eternal. In the meantime, though, just the sight of Yggdrasil calmed the most frantic heart.

The Aesir mistreated the old witch Gullveig, who lived with the Vanir. In revenge, the Vanir prepared to attack. But the Aesir made a preemptive attack. The bloody battle went on for eons.

THE GODS CLASH

The two groups of gods living in the cosmos didn’t trust each other much. Rather, they were wary to the extreme. One day a witch named Gullveig, who lived with the Vanir in Vanaheim, visited the Aesir, living in Asgard. No one’s really sure why, but Gullveig walked into Odin’s hall and blathered about gold, about how it glistened and how much she loved it. The Aesir listened with growing disdain and finally did the unforgivable: They jammed spears into her everywhere. Then they tossed her into a fire and burned her to death. All she had done was annoy them with her incessant talk, and just look what they did to her!

But Gullveig stepped right back out of the flames, alive and whole. A second time they threw her in, and a second time she stepped back out. And yet a third time. By that point the astonished Aesir realized this witch had powers beyond anything they’d dreamed of, so they moved aside and let her wander wherever she wished in the halls of Asgard. Troublemakers followed her; the more wicked the followers, the more they admired Gullveig. Word got back to the Vanir of how dreadfully the Aesir had treated Gullveig. Vengeance seemed a duty; they prepared for war.

From his high seat in Valaskjalf, Odin saw what was happening over in Vanaheim. He saw them sharpening spearheads and polishing shields. So, he prepared a preemptive strike, and the Aesir cast the first spear. But the Vanir were already surging forward on their mounts, trampling the fields between the two worlds.

Berserkers

Odin, Thor, and Frey on a Viking tapestry

In the Icelandic sagas Odin’s warriors put on animal fur coverings. Wolf fur let them fight with trickery. Bear fur let them wrestle with strength. Their fighting bordered on insanity; they went berserk (ber was the Old Norse word for “bear”). The Vikings, likewise, were known for their ferocious frenzy in battle. These “berserkers” terrorized much of northern Europe in the late 700s until the early 900s, but their more mild Norse compatriots settled peacefully throughout the same area.

The battle went on and on. That’s how battles between gods are. Both sides are immensely powerful, after all. But the longer the battle endured, the clearer it became to all that a victor was unlikely. The gods wearied of the futility of this dreary war. Finally, the leaders of the Vanir and the Aesir sat down to hash things out. They couldn’t agree on almost anything, but they wanted so much just to end that plague of war that they drew up a truce. And to show their sincerity, they exchanged hostages: Two from each group would go to live with the other group.

The Vanir sent the very wealthy god Njord and his son Frey to Asgard. Frey’s twin sister, Freyja, and Kvasir, the wisest Vanir, accompanied those two on their journey and ended up staying there. The Aesir welcomed them honorably. Njord and Frey were appointed high priests to preside over sacrifices. Freyja became a sacrificial priestess, and she taught the gods all the spiritual, medical, and magical knowledge that she had, which was considerable.

The Aesir, for their part, sent Hoenir and Mimir to Vanaheim. Hoenir was strong and big; he certainly looked like he’d make a fine leader. And Mimir, though he was a giant, was considered the wisest Aesir—definitely comparable to Kvasir. All seemed good to the Vanir. They put Hoenir in a position of power and Mimir stood to his right and advised him. Together they made shrewd decisions. But if Mimir left Hoenir’s side, the tall and handsome Hoenir turned silent. When asked a question, he refused to speak. The Vanir felt cheated. In fury, they cut off Mimir’s head and sent it back to Odin.

Why they cut off poor Mimir’s head because of closed-mouthed Hoenir is unfathomable. Gods had their own ways of doing things.

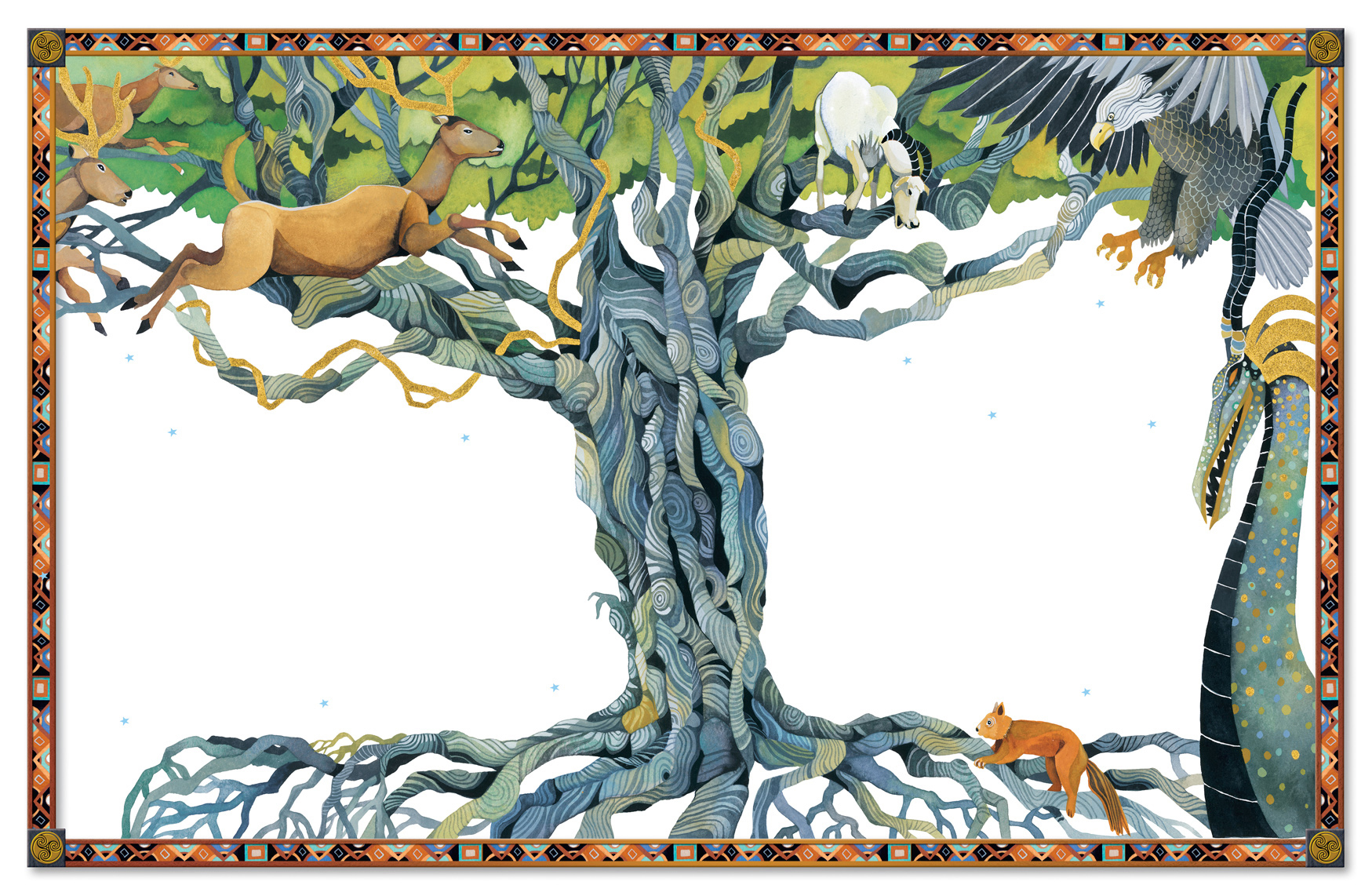

Odin was bereft, for Mimir had been a fine and true friend. He held that severed head in his arms and crooned to it. Then he coated it with herbs that would retard decay and sang magic incantations over it. The head of Mimir regained its power of speech and thenceforth became a font of wisdom for Odin.

The Aesir sent the wise giant Mimir to their rival gods, the Vanir, in an exchange. But the Vanir got angry and cut off poor Mimir’s head. Odin grieved for his lost friend.

And thus the first war in the cosmos began and ended. But it wasn’t the last. Humans waged war often. And the gods treated the corpses of men who died in battle very well. They didn’t go to Hel. No, no. Half of them went to Asgard to live in a special hall called Valhalla, where spear shafts served as rafters and the roof was thatched with shields. At the western door lurked a wolf with an eagle hovering overhead. To arrive in Valhalla, the fallen warriors had to cross a large, noisy river. Once there, Odin welcomed them heartily. He had straw strewn on the benches in the hall to make them comfortable; he had all the goblets polished, for he already foresaw needing these warriors. Someday, he knew, there would be a final great battle among gods, humans, monsters, giants, everyone—the all-consuming Ragnarok. Warriors would be invaluable.

The Valkyries flew on their horses over battlefields and chose the best fallen warriors to bring back to Valhalla. The warriors feasted and practiced their martial arts there, preparing for the great battle of Ragnarok that would come someday.

Odin’s helper maids, the Valkyries, put on silver helmets from which their golden hair flowed out and red corselet armor that emphasized their beautiful bodies, and they rode on white horses through the air over the battlefields below. They must have appeared both terrifying and alluring to the sweaty, exhausted men as they lay dying. The Valkyries carried the chosen dead up to Valhalla.

And what a fine routine met these warriors there in Valhalla. Every night they feasted on overflowing platters of pork from the beast Saehrimnir, roasted in the cauldron Eldhrimnir by the soot-covered cook Andhrimnir. They drank never ending mead that came from the udders of the goat Heidrun, the one that ate the tender shoots of the tree Yggdrasil. Every day they battled together, and those who fell in these heavenly battles simply rose again at the end of the day and marched through the 540 doors of the hall to join the feast anew, since everything regenerated of its own accord.

The other half of the dead on the battlefield were gathered up by the priestess Freyja, the Vanir goddess who had taught everyone in Asgard so much about the wonders of the cosmos. She brought them to her heavenly field called Folkvang, where they, too, were groomed for the final battle, Ragnarok.

It’s as though right from the beginning of time everyone was preparing for the end of it all.

From his throne, Odin could view all nine worlds. Still, he sent out his two ravens to patrol for him and come back with details about happenings in those corners of the cosmos that his eye couldn’t reach.

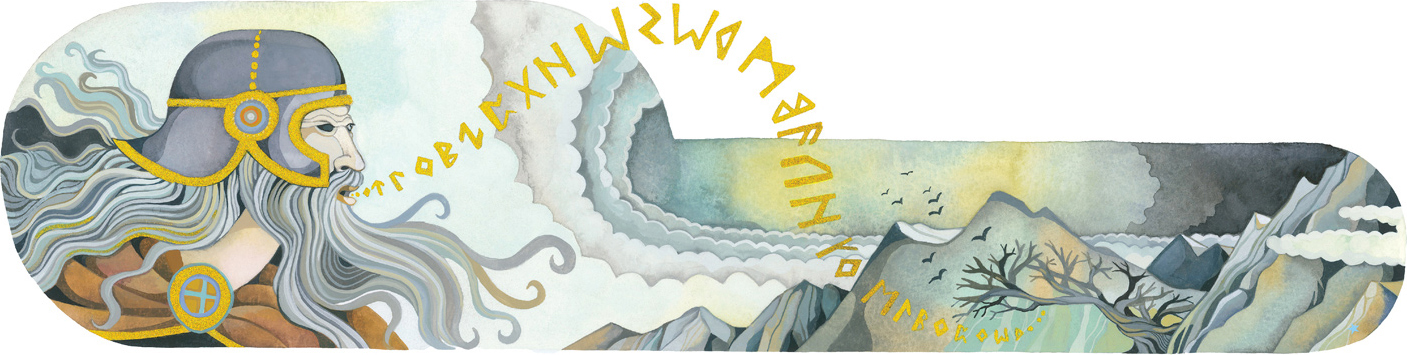

ODIN’S QUEST

Odin was viewed as harsh and severe. And the one he was most severe with was himself.

When Odin sat on his high seat, Hlidskjalf, he could look out over the cosmos and see a great deal. But not everything. Hmmm. What was going on behind that ridge over there in the land of the dark elves? Who was whispering what under that root of Yggdrasil in Hel? His throat was parched with the yearning for knowledge. So he relied on the two ravens that perched on his shoulders: Huginn (Thought) and Muninn (Memory). They flew off in the morning to investigate the nine worlds with their sharp eyes. At night they returned to Odin and told him all that they had witnessed.

Still, it wasn’t enough. Odin’s mind was greedy; knowledge tasted good, but wisdom, ah, that would taste far better.

Odin and the other gods living in Asgard rode their horses every day over the burning bridge, Bifrost. On the other side was the grand ash tree Yggdrasil and the sacred well of destiny.

By this time there were ten major gods in the cosmos beyond Odin (and before too long, there would be two more). Eight of them were Aesir: Odin’s sons Thor, Balder, Tyr, Heimdall, Hod, and Vidar, plus his grandsons Forseti (son of Balder) and Ull (stepson of Thor). The other two major gods lived among the Aesir, but they had come originally from the Vanir: Njord and Frey. Each day Odin and these ten gods rode their horses over Bifrost, the flaming bridge, to that root of the spreading ash tree Yggdrasil that extended to heaven. Beneath that root was the sacred well Urdarbrunn, where the spring of destiny bubbled up. The gods held their assemblies right there. They made decisions that upheld righteousness and justice, and that protected humans against giants and dwarfs and dark elves. As they sat there, Odin watched two swans swimming with a sense of peace he’d never experienced, and he watched the three lovely Norns sprinkle the sacred tree from the spring of destiny and coat its wounds with a clay salve from the well Urdarbrunn. In this watery ritual he recognized something mystical, beyond reason, something that renewed the everlasting tree’s strength, something that gave those swans equanimity. Water did it—water had that unnamed something that could elevate one to an ever greater strength.

That’s when Odin took a closer look at the giant Mimir. Mimir was but a head at this point, severed from his body by the Vanir. But he was still the wisest one in all Asgard. Under another root of Yggdrasil, the one that stretched into the frost giants’ world, Jotunheim, was a well that Mimir guarded, and so it was called Mimisbrunn. Mimir drank from this well each day. Aha! The well was the source of Mimir’s wisdom! Odin had to have at that well.

And so Odin made a deal with Mimir: an eye for a single draught of that well water. Such a high price, this extreme self-mutilation. But what good was an eye that couldn’t fathom what it saw? Odin willingly scooped it from his own skull and hid it. He fashioned a drinking horn from dragon skin, dipped it into the well, and opened his mouth wide. The cool water sloshed down his throat and radiated throughout his essence. Yes, Odin knew more now, much more; he understood, he was wise. But, alas, he now knew that the highest wisdom of all—that of clairvoyance—was yet to be attained.

And where else to attain it than from the sacred tree Yggdrasil itself? Odin pierced himself with his spear Gungnir, perhaps so that he could come close to understanding the pain the tree experienced from its daily wounds. Then he hanged himself from a high bough. For nine long days and nine long nights, he swung there. He allowed no one to ease his suffering—not a drop of water passed his lips. In this delirious state, near death, he saw below him runes. He knew runes; some were carved on the tip of Gungnir—mysterious letters. But now those letters formed in the tree roots and they yielded their meanings to him and taught him nine precious songs and magic charms and the art of poetry. He looked out at the nine worlds in a new way. He shuddered at the knowledge he now embodied—at the miseries that lay ahead, at the deeds that lay behind, at all the difficulties of getting from day to day in a decent way.

Healing Waters

Holy water in the Hindu Tirta Empul Temple in Bali

Sacred wells, rivers, and springs appear in many religions, including those of several indigenous people of the Americas, ancient Rome, and India, as well as Christianity. Likewise, sacred words—here in the form of runes, those mysterious letters that took wisdom to decipher—come up repeatedly. Both are associated with the ability to heal, and, sometimes, to destroy. The Norse poem “Hávamál” claims that runic words heal better than leeches, a hint that old Norse medicine was fighting against the newer Christian methods.

Odin chose to hang himself from Yggdrasil for nine days and nights in his quest for wisdom. He was rewarded with a vision of runes that granted him knowledge of nine magic songs, charms, and poetry.

Odin proclaimed:

Cattle die, kinsmen die,

The self must also die;

but glory never dies,

for the man who is able to achieve it.

Odin determined to achieve glory. In this new state he could connect his own ancestry among the giants to the present race of gods, and with that connection he made a whole of the cosmos. To each its time, its place. Everything fit.

Odin, the clairvoyant, now conversed with everyone. People made human sacrifices to the mighty god. They hanged men from trees and pierced them with spears—mimicking the passion of Odin dangling from Yggdrasil those nine days. Who were these hanged men? Some were dying of disease, and so they dedicated themselves to Odin, to end their lives in the glory of talking with the highest god. Others chose to avoid a natural death by embracing this ceremonial one. And while the men hung there, Odin came to talk with them, to glean what they might know of this life and this death. Odin found solace and pleasure in these shared words. He was proud to be god of the gallows, for dying men told truths.

Odin engaged in this same kind of intimate talk with those fallen on the battlefield. Dead men revealed mysteries—this was an extra advantage of surrounding himself with warriors for the huge war ahead, the one that would come eventually, the dreaded Ragnarok.

Odin thus put his quest for information and, ultimately, understanding of that information before all else. A harsh choice, indeed.

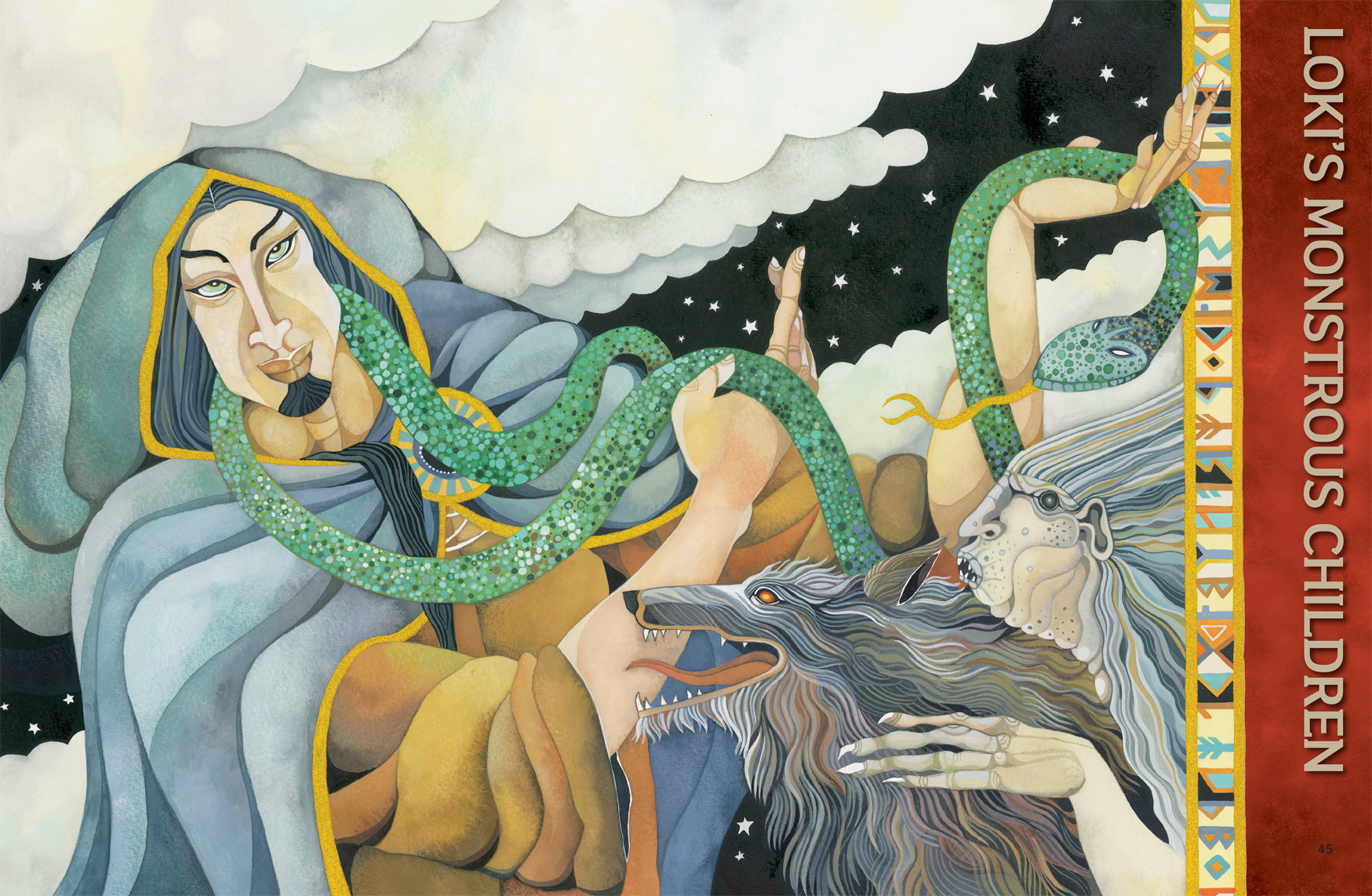

Loki had many offspring, but three were horrendous: the wolf Fenrir, fated to kill Odin in the battle Ragnarok; the serpent Jormungand, whose venom would kill Thor in that battle; and hungry Hel, who would keep Odin’s son, Balder, prisoner.

LOKIS MONSTROUS CHILDREN

Loki made everyone edgy.

Loki was the son of the giant Farbauti and the goddess Laufey. Several gods took giantesses as wives, and their offspring did fine. But it was taboo for a goddess to take a giant as a husband; thus, Loki was born with a giant (so to speak) strike against him. But at one point he and Odin mixed blood and thus became blood brothers. Odin, in fact, promised that he would always share drink with Loki. This meant that Loki was counted among the Aesir.

From the start, Loki was spiteful, and that spirit proved to be inheritable. Hapless wives bore him wretched children, three notable for their evilness: the chaos monsters, children by the frost giantess Angrboda. The first was the vicious wolf Fenrir; the second, the serpent Jormungand; and the third, the horrible hag Hel. At first, the children lived with their mother in Jotunheim. But everyone in Asgard knew they were destined to cause cosmic misery eventually. The gods couldn’t kill these children—for no one can interfere with fate. But they wanted to be rid of them in the meantime. So the one-eyed Odin had a band of gods sneak into Jotunheim one night and gag and bind the giantess Angrboda and kidnap the children.

The wolf Fenrir was the son of Loki and a vicious, frightful creature. Odin had him bound in chains and brought to Asgard. But it was hard to capture him: The god Tyr lost his right hand in doing it.

Tricksters and Sneaks

A Native American rock painting, possibly of Coyote

Tricksters appear in many traditions. Some native tribes of North America have Coyote, a well-known prankster, but he reveals people’s weaknesses, so he’s listened to. The Greek god Hermes was a liar and thief, yet he was eloquent and could convince anyone of anything. Coyote, Hermes, and Loki are shape-shifters. But Coyote is neither good nor evil, Hermes is simply an annoyance, and Loki is wicked. Both Odin and Thor seek Loki out sometimes, however, to use his ability to deceive for good goals.

Odin decided the wolf Fenrir should live in Asgard, perhaps so he could keep an eye on him. After all, Fenrir was destined to kill Odin at the final battle of Ragnarok. The inhabitants of Asgard were not delighted with the prospect of this beast living among them. The only one who dared get close enough to the wolf to feed him was Odin’s son Tyr, whose mother was a giantess and who was bolder than others—a true god of war. Still, as Fenrir grew, fear of him grew until people wanted to tie him up. But they didn’t want Fenrir to realize he was being tied up. They pretended they were having a bet, to see if the wolf was strong enough to break binding chains. Fenrir agreed, and immediately burst from his fetters. The gods made a second chain, twice as strong as the first. Fenrir burst out of it easily. So Odin sent Frey’s servant Skirnir to the dark elves, to ask them to forge a chain strong enough to bind Fenrir. The chain they forged was of the sound of a cat footfall, the beard of a woman, the roots of a mountain, the sinews of a bear, the breath of fish, and the spit of birds. This chain was called Gleipnir, and it brushed against your skin soft as silk. The gods took Fenrir to the island Lyngvi in the lake Amsvartnir and asked him to submit to being tied with Gleipnir.