Полная версия

Treasury of Egyptian Mythology: Classic Stories of Gods, Goddesses, Monsters & Mortals

But Ra didn’t wait for anything; it wasn’t in his nature. He looked at the bow Nut’s body formed and all those words that filled his heart now spilled out of his mouth in a new form: stories. Ra became brilliant like Nut, brilliant with stories. He had to tell those stories, those stories could make anything happen, anytime, anywhere.

Shu lifted his daughter Nut; the drape of her body formed the sky. He left his son Geb lying at his feet; the expanse of Geb’s body formed the earth.

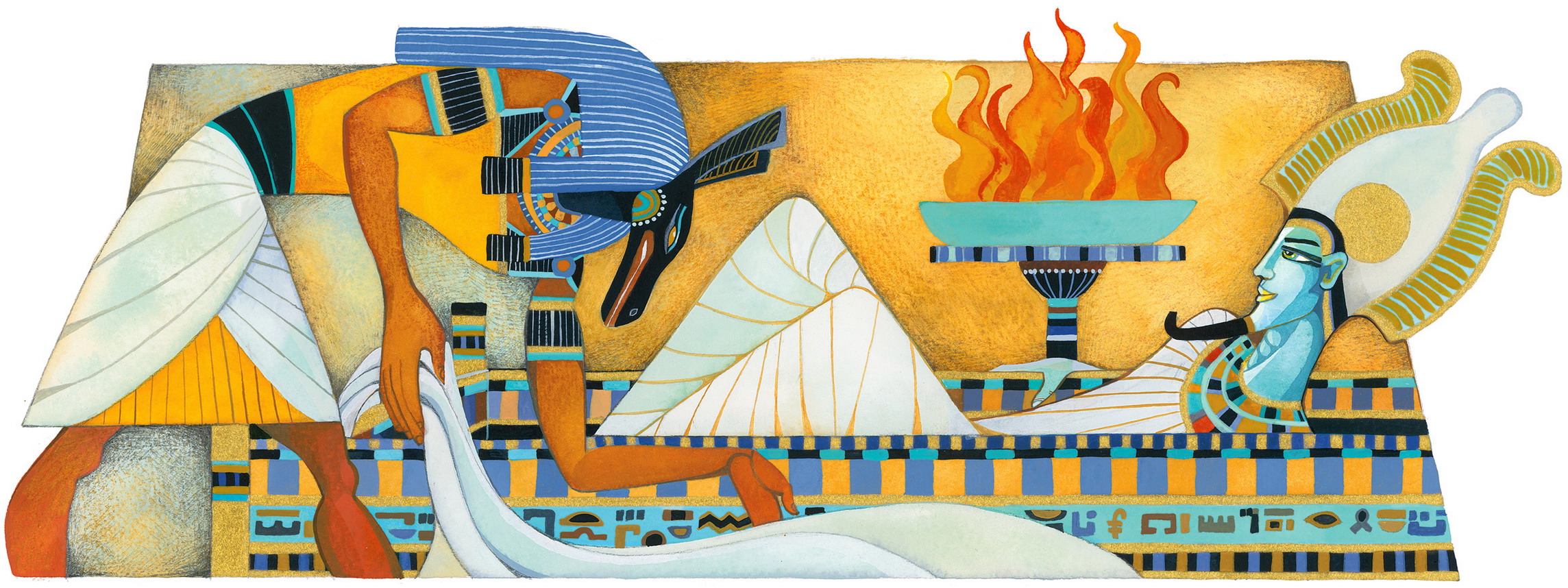

Ra snuck behind the mountain Manu (which appeared even as he said the name) and climbed into his boat Manjet (again gaining solidity as it was named, yet somehow being as old as forever, millions upon millions of years old) and sailed across the sky as a glowing ball of fire that appeared to roll over Nut’s thighs and buttocks and spine and neck. He landed in the far west horizon (since the directions now existed as he spoke them) and then journeyed back to Manu, to his starting point, this time traveling through the underworld Duat in his second boat, Mesektet.

Manjet carried Ra across the sky, as he changed from a morning babe to an evening sage. Imagine how strange it must have felt to experience a lifetime each day.

There was something exhilarating and renewing at the start of the journey across the sky and something tiring and withering at the end. A tantalizing mix. Ra had to repeat it; it was far too involving to experience only once. He allowed himself to be born again, coming out through Nut as though she were his mother rather than his granddaughter, reversing the order of things, confusing time by letting it circle back on itself. He rose as a baby. By midday, when the boat Manjet arrived at the first knob of Nut’s spine, he was a man in the prime of life, a hero ready to tackle any problem and win. He set in the evening as an old man, tottering on a short stick, a flame fanning to a flicker of heat and finally a memory of warmth. What a journey. What a thrill. He had to repeat it forever.

And so a new order was formed. The sun god Ra defined the fundamental rhythm of life. But disorder could never disappear now; life entails it. And Ra’s words ensured it.

Pay attention, all.

Behold my majesty.

I am the Lord of Radiance.

I am the father of all, the lover of strength, the giant of victory.

So now, let us conquer.

Conquer? What could that mean? Who was there to conquer? Where was the disorder, the discord, that would require vanquishing? Ra couldn’t see it yet. But he knew beyond a doubt it was coming.

THE GREAT PESEDJET

A Hierarchy of Gods

The sun god Ra created himself, then his children: the air god Shu and the moisture goddess Tefnut. They created their children: the earth god Geb and the sky goddess Nut. Now the ball was rolling; Geb, in all his lush splendor with plants growing from him, and Nut, in all her quiet splendor with winds caressing her, did their part, singly and together. Soon there were five children in the next generation: the goddess Nebet Hut and her husband-brother god Set, the goddess Aset and her husband-brother god Usir, and the god Heru Wer. Ra was progenitor to nine more deities now, the Great Pesedjet. (See illustration)

Ra had been pleased at the triad that he and Shu and Tefnut formed. But now, all these progeny totaled nine, and nine was better. Nine was three squared. A nine-pointed star could be formed by superimposing three identical equilateral triangles, so that each was rotated precisely 40 degrees over from the next lower one. A magic square could be formed by making a matrix of nine cells within a square, each one filled with a distinct numeral from 1 to 9, where the numbers in each row, the numbers in each column, and the numbers in each of the two diagonals added up to the same total. The geometric and algebraic games one could play with nine were a delight. They were a promise of an extraordinary future. And the best thing about the Great Pesedjet was that Ra’s great-grandson Heru Wer was really just the embodiment of Ra himself at midday. So Ra could count himself as part of this miraculous nine. Ra was pleased beyond measure.

Hut Heru was grace itself, enriching the world with the joys of the senses. She was dance and music, inextricably intertwined, and decoratively beautiful, night and day.

That pleasure excited Ra into an even more heated frenzy of creativity that needed to live up to the cleverness of the number nine. The molten flow that had emerged from the watery Nun with Ra’s first words still sizzled. It now inspired Ra. With flame coming from his pointing finger he made the basic elements to build all things. He started with iron and blew it over this rapidly forming ball of a world. It glittered golden. A royal satisfaction enveloped Ra; this was fated to be his color, the rightful color of the father of everything and everyone.

But the world needed more colors. Another jab of Ra’s fire fingertip scattered red lithium to the winds. Next calcium burned bright orange. Then sodium flamed yellow, copper sparkled green, selenium glowed blue, cesium flashed indigo, potassium gave violet luster.

The luminosity of colors seduced Ra’s new eye to step forward as a goddess, and she called herself Hut Heru. She danced over the earth, on which the iron had now cooled into a crust, and laughed, filling the cosmos with music. The twirling of her skirts swished the remaining gassy colors high. When the sun god Ra shone his light through the moisture goddess Tefnut, a rainbow arched across the world, echoing the arched body of Nut, the daughter of Tefnut and Shu.

Hut Heru didn’t always dance, though. She loved night. She lay back in those hours and gazed upward into nothingness. So she wanted calming colors for those quiet times. Ra knew this, of course, for Hut Heru was his very eye. With a scorching finger, he made the silver of aluminum. From it the stars and moon formed, and Hut Heru was glad and grateful.

Now there were nine colors. Nine again. Luscious nine.

Ra shrugged and a cloud of insects filled the air in all imaginable colors. He loved scarabs best. They rolled dung into balls and laid their eggs inside, so the little balls emitted heat as the dung decayed. Later, when the eggs hatched, it seemed like spontaneous generation—like the self-generation of the royal Ra. What charming creatures! Ra took to assuming scarab form and calling himself Ra-Khepra in the morning, when he was just a babe pushing the sun up into the sky. From then on the scarab was sacred before all other creatures.

But the insects swarmed, far too many, plaguing the Pesedjet of deities. So the tongue of Ra stepped forward, as the god Tehuti, and with ever-powerful words he created birds to eat them. Clever Ra was wiser now about the ways of life, so he didn’t stop there; he made Tehuti speak again, and now some birds preyed upon others, to keep the pop-ulations of both insects and birds under control. The master predator and most intelligent was the falcon, and so Ra declared it his bird. Ra often assumed the head of a falcon, particularly in midday at the sun’s zenith. In that form he called himself Ra-Herakhty.

The falcons were such skillful hunters, they would soon have eaten up all the smaller birds except for the fact that they had the snakes to prey upon, as well. Perfect.

There was a whole world to fill, and Ra did it all. Just a blink, a shrug, a chin flick, and wings flapped, feet scurried, bodies wriggled.

And those snakes—good glory, what killers the cobras were! Their tongues picked up the faintest smells and the pits behind their nostrils were so sensitive to heat that they could hunt even at night. Ra had been brilliant to add the sacred iaret to his headdress.

Through words, Ra created little creatures of land and sea and air. Then medium-size ones. Then enormous ones. He created plants and mushrooms. He created rocks and metals and gases. And it was all so painfully beautiful.

Ra gazed at the world through his new eye Hut Heru, wearing his sacred iaret, and the complexity impressed him—the deities, the plants, the beasts, the humans. But somehow those humans kept worrying him. They were cunning in a different way from the beasts. Ra had the terrible sense that he had known those humans would bring trouble, that he had willfully played his part. This was how it had to be. And just as strongly he felt all creation was teetering, close to going out of control.

Set: The god Set appeared as a mix of parts from different animals: aardvark, jackal, donkey. Over time, he came to be viewed as increasingly evil. Perhaps this conglomeration reflects the lack of peace within him.

SET (SETH)

Envious God

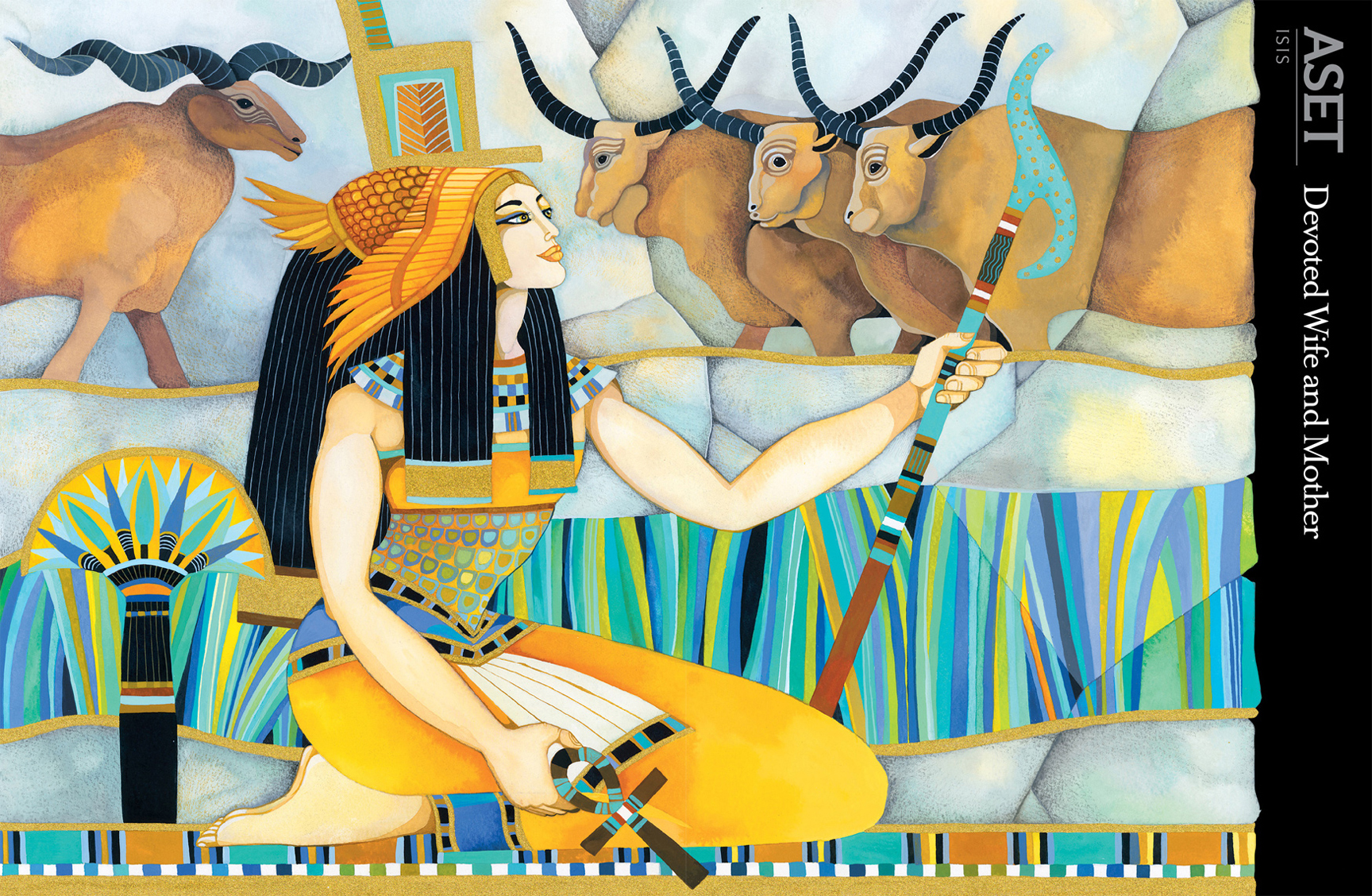

The goddess Aset, great-granddaughter of Ra, was beautiful in every way. Humans gravitated toward her naturally. She listened to the worries, hopes, dreams of everyone, from the richest to the slaves. She listened to those who were abused and even to their abusers. And by listening, she helped them understand their own thoughts and find their own paths to solving their troubles or fulfilling their dreams. In a sense, it was through Aset’s faithful and careful listening that human beings really learned to trust in the deities. She wished strength and health for all of them; she wished good life. And so she wore the tjet, a girdle with a knot at the front, and carried in one hand the ankh, a small straight key with two straight arms and a loop on top. Both the tjet and the ankh were symbols of life. In her other hand she often held a simple wooden staff.

That wooden staff was useful when she walked with her brother-husband Usir in the fields. Usir loved to wander among the animals, particularly the animals that humans quickly gathered around them. And even more particularly those fat woolly sheep with the wide-set eyes that made that little baaa baaa noise Aset found so pleasing. In fact, Usir was so fond of sheep, he wore ram horns on his crown. He was a benevolent god, bringing robustness to the sheep and fertility to the land. He taught humans to plow and he gave them laws to live by, rising to become king of Lower Egypt and then, so popular was he, king of all Egypt. And so it was impossible for this benevolent god not to love his ever-so-benevolent wife Aset. He adored her. They were meant for each other.

Their brother god Set watched them gaze at each other, this Aset and this Usir, eavesdropping on their fond murmurings. He could smell how they changed when they approached each other. Usir grew musky, like a young ram; his muscles rippled under his skin. Aset became as fragrant as those water flowers she picked so often, those blue lotuses. She grew intoxicating, as though her very essence was lotus oil.

Set had a sister-wife of his own—what was her name? Ah, yes, Nebet Hut. But Set couldn’t think about her. He couldn’t even look at her. He looked instead at Aset.

THE LOTUS: God Scent

Ancient Egypt had both white and blue lotuses, and from both an oil can be extracted that is pungently sweet to smell. People used the flowers as decoration and women used the essence of the lotus as perfume. Egyptian perfumes have been famous from ancient times through modern times. But the blue lotus also has a high plant nutrient content, so this flower may have been used by the ancients in medicines for its healing properties.

Blue lotus flowers are still used in perfume manufacture today.

All that love heaped on his brother galled Set. Alas, he couldn’t think of anything else, he couldn’t enjoy ordinary things, he couldn’t love anyone.

And he looked at Usir. He looked until his eyes burned as dry as the desert he prowled.

Then the strands of envy twisted even tighter around Set’s innards, for his brother Usir fawned over Set’s son Inpu. Set’s teeth went grimy with disgust. And Inpu, the ingrate, he responded to this attention, caring for his uncle Usir too much—he even seemed to take after him. Intolerable—it was Set the boy should love like that! So Set was glad when the boy left home to go work in the underworld Duat. Who needed such a son around?

But still Set had to watch Aset’s face as she gazed at Usir. And now he looked around and noticed how humans adored this sister and this brother that they had chosen as their queen and king, and his top lip curled. There were so many humans by now—they just kept multiplying. And that meant Set’s brother Usir was king of far too much, and was loved by far too many.

Sometimes a brother doesn’t need a reason to be spiteful toward another brother. Set was almost sure he would have hated Usir no matter what, regardless of how Aset loved him, regardless of how his own son Inpu admired him. But the way all those people loved Usir—well, that went beyond the pale. King of Egypt! Bah! Set’s insides swirled like the very strongest of tempests, with lightning and thunder and shrieking winds—and in this stormy state he vowed to himself to crush Usir.

Set held a banquet. He arranged cones of scented fat in a large circle and set them ablaze to keep away pesky mosquitoes. He gave the goddesses lotus flower necklaces—knowing, of course, that this would endear him to Aset. He filled a basin with sparkling clean water for everyone to wash their hands in. Then he served them bread and great quantities of beer. As they were lolling around, satiated, he pulled a cloth away to reveal a beautiful box.

Usir ran his hand appreciatively along the intricate carvings. “Where did you get this, brother?”

Usir slid happily into the majestic cedar box. It felt like the most comfortable of beds. How cold must Set’s heart have been, planning the doom ahead.

The combination of gold gilt, the color so dear to the great god Ra, and deep blue paint, the color so dear to his beloved wife Aset, made the box nearly irresistible to the unsuspecting Usir.

“It’s superb, isn’t it?” Set leaned in toward Usir with a brotherly intimacy. “Tell you what. Whoever fits perfectly in this box, well, that’s the rightful owner of it. I will regale that person with this fine box.”

Each guest took a turn at lying in the box. But each was too short or too long or too fat or too thin. In contrast, Usir fit perfectly. Naturally. For Set had taken all the relevant measures of his brother as he slept, and had the box built just so.

The instant Usir lay inside, Set and his helpers rushed forward, closed the lid, and sealed it. Set lifted the box over his head and flung it with all his might into the raging Nile River. And for the first time in so long he couldn’t remember, Set felt triumph. He was rid of Usir, rid of the scourge of his life. At last, he could be all he wanted to be; he stood in no one’s shadow.

Such is the brutality unchecked envy can wreak.

But good has its own way of responding—and both Aset and Usir were deeply good. This story was far from its end.

Aset: Aset loved lotuses, the symbol of Upper Egypt. Usir loved papyrus reeds, the symbol of Lower Egypt, especially where the Nile flows into the sea. Together they made the perfect ruling couple for all Egypt.

ASET (ISIS)

Devoted Wife and Mother

The god Set was so envious of his brother Usir that he committed a dastardly act. He nailed Usir into a box and threw it into the Nile River.

“Ahiii,” screamed Aset. She ran along the shore, arms outstretched futilely. She must catch up, she must pull the box to safety. She imagined her husband trapped inside, panicked. She ran.

But the current raced north, carrying her husband inexorably toward the sea. And the wind blew south, impeding Aset’s every step. She ran hard, seeing the white-foamed swirl of the swift and wild river. She ran harder, hearing nothing but the shriek of the wind rasping her ears raw. The box was already out of sight! Aset had to run yet faster. That was her husband—the love of her life!

Aset ran all that day, all that night, all the next day. Her feet bled. Her legs ached. When she arrived at the seashore, she raced back and forth, calling out over the green and blue and purple waters, calling, calling. She rent her hair. She grabbed a clamshell and shaved off her eyebrows. She beat her chest.

The world spun around this goddess, this woman in love, bereft and alone, who had no choice but to prostrate herself on the beach and wait for the dizziness to pass and hope against hope that her husband had managed to get out of the box before he suffocated.

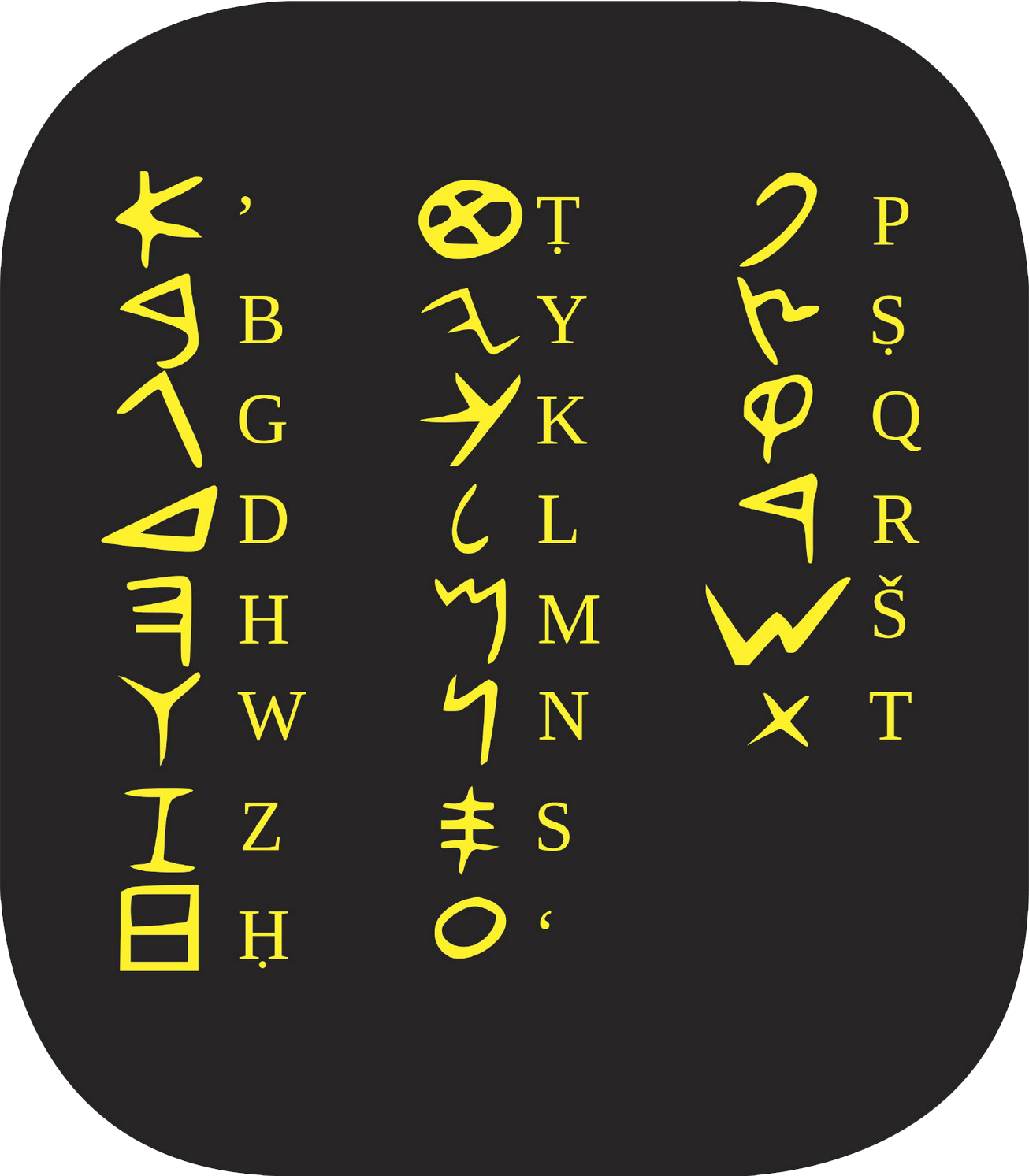

Our Alphabet’s History

The Kenaani’s land became known as Phoenicia. It spread between the River Jordan and the Mediterranean Sea. The people were known for sea trading and purple dye made from murex snails. But we know them most for their abjad, a writing system with letters that represented consonant sounds. The Greeks borrowed this abjad and added letters for vowels. The Etruscans then borrowed it, then the Romans, each making changes—hence our alphabet.

A tablet showing the Phoenician alphabet

Meanwhile the box that held Usir had washed out to the middle of the vast Mediterranean Sea and floated in that wadj wer—that great green—aimlessly, a rudderless, sail-less skiff, until the currents eventually carried it toward shore again. But not back to the mouth of the Nile where miserable Aset lay crying, no. The box settled far to the east, near the city of Kubna in the land of the Kenaani.

The coast there was thick with strong reeds that reached out. Like tentacles, they slipped around and over and under each other and pulled the box in, wrapping themselves about it over and over, caressingly. Somehow one reed pushed against another so insistently that the two reeds merged, and then another merged with them, and soon the mass of reeds was a single shrub engulfing the box. And then the shrub grew.

This sort of magic doesn’t happen every day—and magic it surely was. For inside that box lay the corpse of the god Usir, who had known how to bring fertility to the earth, who could make anything grow. So perhaps that very power had transferred from the god to the box as he gave his last breath. Who can know such a thing? Yet that shrub grew faster than any shrub had ever grown before, and became a massive cedar tree, 130 feet tall, studded with cones. Hoopoe birds came in droves to give themselves sand baths under the tree and to nest among its silver-green needle-like leaves.

The mighty cedar could be seen from afar, but it could be smelled even before it was seen, for it gave off a spicy, alluring aroma. Soon the king himself noticed the tree, and he called his queen to his side to inhale its essence. She swooned at the cedar perfume. After all, she was late in her pregnancy and she was given to swooning.

There was no question about it: The tree was majestic, it must grace the king’s palace. It took a troop of workers to cut through the base and haul the tree to the palace, where it became a beautiful column that all could admire. And they did. The column made them feel a certain peace; it offered a sense of assurance that all would be well with the world. It was almost godly in that way. Yet still, no one guessed that inside the trunk nestled the box that held Usir.

The gigantic cedar that held Usir’s trunk was one of many colossal trees in that land. They could live thousands of years. But this tree was doomed.

Grief-stricken Aset somehow sensed the birds knew best. She followed their calls to the palace of Kubna, where her husband Usir was hidden within the cedar column.

Back on the shore of Egypt, the goddess Aset lay desperate. Moons had passed and still she remained immobile. But now she was woken from her grief-stricken stupor by the insistent calls bu bu bu, and again bu bu bu, all around her bu bu bu. She sat up, agog at the flock of hoopoes with their colorful crests, strutting in profusion. These were the birds who had nested in the cedar the king had cut down; they were mourning its loss. They had flown all this way searching for a substitute tree when they’d spotted Aset, and instinctively they were drawn to her, instinctively they understood her grief matched theirs.

The birds called bu bu bu and Aset stood. Bu bu bu. The birds took to the air and circled above her. Aset followed, and the procession moved east, a wavering line along the sands, a spiraling in the heavens.

Aset sensed an urgency in the birds and hope swelled her heart. These birds were leading her to Usir. What else could this mean? With each day her hopes grew till her heart was ready to shred.

There, at long last, was the splendid palace of Kubna. Aset wandered, sure the box would be just past that wall, just ’round that corner, just under that eave. But the box was nowhere!

Without warning, without preamble, reason finally coated Aset’s tongue with a bitter salt: Usir was dead. Whether she found the box or not, he was dead. It was almost as though he was nearby, with his spirit telling her that, forcing her to understand.

Aset found a large, smooth, warm rock in the courtyard. She sat and wept. But these were tears of acceptance and exhaustion. It was over. At last.

So she thought.

But inside the Kubna palace the royal handmaidens whispered. A morose stranger sat in the courtyard. She was thin as a wind-whipped pine, but still one could see a beauty in those cheekbones, that long neck, those cupped hands. The royal handmaidens peeked out at her, wary at first, but then, gradually, worried for her. Grief weighed on the stranger so heavily, it hurt them to watch. This woman was broken. They approached on quiet feet.

Aset turned and saw their frightened faces and her wounded heart opened. After all, her grief was due to no fault of theirs. She smiled through tears and patted the empty spot on the rock beside her. These handmaidens were hardly older than girls, innocent and fresh. She plaited their hair and exhaled perfume onto their golden skin, and when they asked what had happened to her, she talked sweetly of nothing. Deities knew that humans weren’t good at discussions about death.