Полная версия

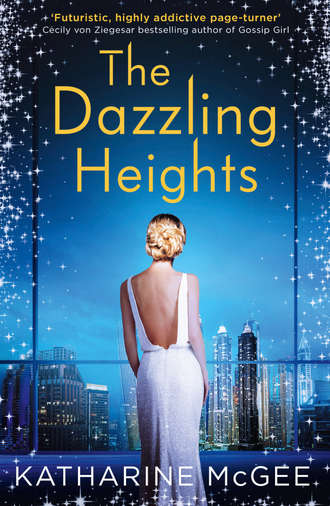

The Dazzling Heights

First published in the USA by HarperCollins Publishers Inc in 2017

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Children’s Books in 2017

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd,

HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

The HarperCollins website address is:

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Copyright © 2017 by Alloy Entertainment and Katharine McGee

All rights reserved.

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

Cover photographs © Ilina Simeonova / Trevillion Images;

Westend61 / Getty; Hongqi Zhang Alamy; Shutterstock.com.

Katharine McGee asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008179946

Ebook Edition © 2017 ISBN: 9780008179939

Version: 2017-07-26

For my parents

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

Mariel

Leda

Calliope

Avery

Watt

Rylin

Calliope

Rylin

Leda

Watt

Rylin

Calliope

Avery

Leda

Avery

Rylin

Watt

Rylin

Calliope

Avery

Rylin

Watt

Avery

Calliope

Leda

Avery

Rylin

Calliope

Avery

Leda

Rylin

Avery

Watt

Calliope

Avery

Leda

Rylin

Calliope

Rylin

Avery

Watt

Leda

Rylin

Watt

Calliope

Watt

Avery

Calliope

Rylin

Calliope

Watt

Leda

Avery

Calliope

Leda

Watt

Avery

Rylin

Leda

Watt

Mariel

Acknowledgments

Keep Reading …

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE

IT WOULD BE several hours before the girl’s body was found.

It was late now; so late that it could once again be called early—that surreal, enchanted, twilight hour between the end of a party and the unfurling of a new day. The hour when reality grows dim and hazy at the edges, when nearly anything seems possible.

The girl floated facedown in the water. Above her stretched a towering city, dotted with light like fireflies, each pinprick an individual person, a fragile speck of life. The moon gazed over it all impassively, like the eye of an ancient god.

There was something deceptively peaceful about the scene. Water flowed around the girl in a serene dark sheet, making it seem that she was merely resting. The tendrils of her hair framed her face in a soft cloud. The folds of her dress clung determinedly to her legs, as if to protect her from the predawn chill. But the girl would never feel cold again.

Her arm was outstretched, as though she were reaching for someone she loved, or maybe to ward off some unspoken danger, or maybe even in regret over something she had done. The girl had certainly made enough mistakes in her too-short lifetime. But she couldn’t have known that they would all come crashing down around her tonight.

After all, no one goes to a party expecting to die.

MARIEL

Two months earlier

MARIEL VALCONSUELO SAT cross-legged on her quilted bedspread in her cramped bedroom on the Tower’s 103rd floor. There were countless people in every direction, separated from her by nothing but a few meters and a steel wall or two: her mother in the kitchen, the group of children running down the hallway, her neighbors next door, their voices low and heated as they fought yet again. But Mariel might as well have been alone on Manhattan right now, for all the attention she gave them.

She leaned forward, clutching her old stuffed bunny tight to her chest. The watery light of a poorly transmitted holo played across her face, illuminating her sloping nose and prominent jaw, and her dark eyes, now brimming with tears.

Before her flickered the image of a girl with red-gold hair and a piercing, gold-flecked gaze. A smile played around her lips, as if she knew a million secrets that no one could ever guess, which she probably did. In the corner of the image, a tiny white logo spelled out INTERNATIONAL TIMES OBITUARIES.

“Today we mourn the loss of Eris Dodd-Radson,” began the obituary’s voice-over—narrated by Eris’s favorite young actress. Mariel wondered what absurd sum Mr. Radson had paid for that. The actress’s tone was far too perky for the subject matter; she could just as easily have been discussing her favorite workout routine. “Eris was taken from us in a tragic accident. She was only seventeen.”

Tragic accident. That’s all you have to say when a young woman falls from the roof under suspicious circumstances? Eris’s parents probably just wanted people to know that Eris hadn’t jumped. As if anyone who’d met her could possibly think that.

Mariel had watched this obit video countless times since it came out last month. By now she knew the words by heart. Oh, she still hated it—the video was too slick, too carefully produced, and she knew most of it was a lie—but she had little else by which to remember Eris. So Mariel hugged her ratty old toy to her chest and kept on torturing herself, watching the video of her girlfriend who had died too young.

The holo shifted to video clips of Eris at different ages: a toddler, dancing in a magnalectric tutu that lit up a bright neon; a little girl on bright yellow skis, cutting down a mountain; a teenager, on vacation with her parents at a fabulous sun-drenched beach.

No one had ever given Mariel a tutu. The only times she’d been in snow were when she ventured out to the boroughs, or the public terraces down here on the lower floors. Her life was so drastically different from Eris’s, yet when they’d been together, none of that had seemed to matter at all.

“Eris is survived by her two beloved parents, Caroline Dodd and Everett Radson; as well as her aunt, Layne Arnold; uncle, Ted Arnold; cousins Matt and Sasha Arnold; and her paternal grandmother, Peggy Radson.” No mention of her girlfriend, Mariel Valconsuelo. And Mariel was the only one of that whole sorry lot—aside from Eris’s mom—who had truly loved her.

“The memorial service will be held this Tuesday, November first, at St. Martin’s Episcopal Church, on floor 947,” the holo actress went on, finally managing a slightly more somber tone.

Mariel had attended that service. She’d stood in the back of the church, holding a rosary, trying not to break out into a scream at the sight of the coffin near the altar. It was so unforgivingly final.

The vid swept to a candid shot of Eris on a bench at school, her legs crossed neatly under her plaid uniform skirt, her head tipped back in laughter. “Contributions in memory of Eris can be made to the Berkeley School’s new scholarship fund, the Eris Dodd-Radson Memorial Award, for underprivileged students with special qualifying circumstances.”

Qualifying circumstances. Mariel wondered if being in love with the dead scholarship honoree counted as a qualifying circumstance. God, she had half a mind to apply for the scholarship herself, just to prove how screwed up these people were beneath the gloss of their money and privilege. Eris would have found the scholarship laughable, given that she’d never shown even a slight interest in school. A prom drive would have been much more her style. There was nothing Eris loved more than a fun, sparkly dress, except maybe the shoes to match.

Mariel leaned forward and reached out a hand as if to touch the holo. The final few seconds of the obit were more footage of Eris laughing with her friends, that blonde named Avery and a few other girls whose names Mariel couldn’t remember. She loved this part of the vid, because Eris seemed so happy, yet she resented it because she wasn’t part of it.

The production company’s logo scrolled quickly across the final image, and then the holo dimmed.

There it was, the official story of Eris’s life, stamped with a damned International Times seal of approval, and Mariel was nowhere to be seen. She’d been quietly erased from the narrative, as if Eris had never even met her at all. A silent tear slid down her cheek at the thought.

Mariel was terrified of forgetting the only girl she’d ever loved. Already she’d woken up in the middle of the night, panicked that she could no longer visualize the exact way Eris’s mouth used to lift in a smile, or the eager snap of her fingers when she’d just thought of some new idea. It was why Mariel kept watching this vid. She couldn’t let go of her last link to Eris, forever.

She sank back into her pillows and began to recite a prayer.

Normally praying calmed Mariel, soothed the frayed edges of her mind. But today she felt scattered. Her thoughts kept jumping every which way, slippery and quick like hovers moving down an expressway, and she couldn’t pin down a single one of them.

Maybe she would read the Bible instead. She reached for her tablet and opened the text, clicking the blue wheel that would open a randomized verse—and blinked in shock at the location it spun her to. The book of Deuteronomy.

You shall not show pity: but rather demand an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth, burn for burn, wound for wound … for this is the vengeance of the Lord …

Mariel leaned forward, her hands closing tight around the edges of the tablet.

Eris’s death wasn’t a drunken accident. She knew it with a primal, visceral certainty. Eris hadn’t even been drinking that night—she’d told Mariel that she needed to do something “to help out a friend,” as she’d put it—and then, for some inexplicable reason, she’d gone up to the roof above Avery Fuller’s apartment.

And Mariel never saw her again.

What had really happened in that cold, thin air, so impossibly high? Mariel knew there were ostensibly eyewitnesses, corroborating the official story that Eris was drunk and slipped off the edge to her death. But who were these eyewitnesses, anyway? One was surely Avery, but how many others were there?

An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth. The phrase kept echoing in her mind like cymbals.

A fall for a fall, a voice inside her added.

LEDA

“WHAT ROOM SETTING would you prefer today, Leda?”

Leda Cole knew better than to roll her eyes. She just perched there, ramrod-straight on the taupe psychology couch, which she refused to lie back on no matter how many times Dr. Vanderstein invited her to. He was deluded if he thought reclining would encourage her to open up to him.

“This is fine.” Leda flicked her wrist to close the holographic window that had opened before her, displaying dozens of décor options for the color-shifting walls—a British rose garden, a hot Saharan desert, a cozy library—leaving the room in this bland base setting, with beige walls and a vomit-colored carpet. She knew this was probably a test she kept on failing, but she derived a sick joy from forcing the doctor to spend an hour in this depressing space with her. If she had to suffer through this appointment, then so did he.

As usual, he didn’t comment on her decision. “How are you feeling?” he asked instead.

You want to know how I’m feeling? Leda thought furiously. For starters, she’d been betrayed by her best friend and the only boy she’d ever really cared about, the boy she’d lost her virginity to. Now the two of them were together even though they were adopted siblings. On top of that, she’d caught her dad cheating on her mom with one of her classmates—Leda couldn’t bring herself to call Eris a friend. Oh, and then Eris had died, because Leda had accidentally pushed her from the roof of the Tower.

“I’m fine,” she said briskly.

She knew she’d have to offer up something more expansive than “fine” if she wanted to get out of this session easily. Leda had been to rehab; she’d learned the scripts. She took a deep breath and tried again. “What I mean is, I’m recovering, given the circumstances. It’s not easy, but I’m grateful to have the support of my friends.” Not that Leda actually cared about any of her friends right now. She’d learned the hard way that none of them could be trusted.

“Have you and Avery spoken about what happened? I know she was up there with you, when Eris fell—”

“Yes, Avery and I talk about it,” Leda interrupted quickly. Like hell we do. Avery Fuller, her so-called best friend, had proved to be the worst of them all. But Leda didn’t like hearing it spoken aloud, what had happened to Eris.

“And that helps?”

“It does.” Leda waited for Dr. Vanderstein to ask another question, but he was frowning, his eyes focused on the near distance as he studied some projection that only he could see. She felt a sudden twist of nausea. What if the doctor was using a lie detector on her? Just because she couldn’t see them didn’t mean this room wasn’t equipped with countless vitals scanners. Even now he might be tracking her heart rate or blood pressure, which were probably spiking like crazy.

The doctor gave a weary sigh. “Leda, I’ve been seeing you ever since your friend died, and we haven’t gotten anywhere. What do you think it will take, for you to feel better?”

“I do feel better!” Leda protested. “All thanks to you.” She gave Vanderstein a weak smile, but he wasn’t buying it.

“I see you aren’t taking your meds,” he said, changing tack.

Leda bit her lip. She hadn’t taken anything in the last month, not a single xenperheidren or mood stabilizer, not even a sleeping pill. She didn’t trust herself on anything artificial after what had happened on the roof. Eris might have been a gold-digging, home-wrecking whore, but Leda had never meant to—

No, she reminded herself, clenching her hands into fists at her sides. I didn’t kill her. It was an accident. It’s not my fault. It’s not my fault. She kept repeating the phrase over and over, like the yoga mantras she used to chant at Silver Cove.

If she repeated it enough, maybe it would become true.

“I’m trying to recover on my own. Given my history, and everything.” Leda hated bringing up rehab, but she was starting to feel cornered and didn’t know what else to say.

Vanderstein nodded with something that seemed like respect. “I understand. But it’s a big year for you, with college on the horizon, and I don’t want this … situation to adversely affect your academics.”

It’s more than a situation, Leda thought bitterly.

“According to your room comp, you aren’t sleeping well. I’m growing concerned,” Vanderstein added.

“Since when are you monitoring my room comp?” Leda cried out, momentarily forgetting her calm, unfazed tone.

The doctor had the grace to look embarrassed. “Just your sleep records,” he said quickly. “Your parents signed off on it—I thought they had informed you …”

Leda nodded curtly. She’d deal with her parents later. Just because she was still a minor didn’t mean they could keep invading her privacy. “I promise, I’m fine.”

Vanderstein was silent again. Leda waited. What else could he do, authorize her toilet to start tracking her urine the way the ones in rehab did? Well, he was welcome to it; he wouldn’t find a damned thing.

The doctor tapped a dispenser in the wall, and it spit out two small pills. They were a cheerful pink—the color of children’s toys, or Leda’s favorite cherry ice whip. “This is an over-the-counter sleeping pill, lowest dose. Why don’t you try it tonight, if you can’t fall asleep?” He frowned, probably taking in the hollow circles around her eyes, the sharp angles of her face, even thinner than usual.

He was right, of course. Leda wasn’t sleeping well. She dreaded falling asleep, tried to stay awake as long as she could, because she knew the horrific nightmares that awaited her. Whenever she did drift off, she woke almost instantly in a cold sweat, tormented by memories of that night—of what she’d hidden from everyone—

“Sure.” She snatched the pills and shoved them into her bag.

“I’d love for you to consider some of our other options—our light-recognition treatment, or perhaps trauma re-immersion therapy.”

“I highly doubt reliving the trauma will help, given what my trauma was,” Leda snapped. She’d never bought into the theory that reliving your painful moments in virtual reality would help you move past them. And she didn’t exactly want any machines creeping into her brain right now, in case they could somehow read the memory that lay buried there.

“What about your Dreamweaver?” the doctor persisted. “We could preload it with a few trigger memories of that night and see how your subconscious responds. You know that dreams are simply your deep brain matter making sense of everything that has happened to you, both joyful and painful …”

He was saying something else, calling dreams the brain’s “safe space,” but Leda was no longer listening. She’d flashed to a memory of Eris in ninth grade, bragging that she’d broken through the Dreamweaver’s parental controls to access the full suite of “adult content” dreams. “There’s even a celebrity setting,” Eris had announced to her rapt audience, with a knowing smirk. Leda remembered how inadequate she’d felt, hearing that Eris was immersed in steamy dreams about holo-stars while Leda couldn’t even imagine sex.

She stood up abruptly. “We need to end this session early. I just remembered something I have to go take care of. See you next time.”

She quickly stepped out the frosted flexiglass door of the Lyons Clinic, perched high on the east side of the 833rd floor, just as her eartennas began to chime a loud, brassy ringtone. Her mom. She shook her head to decline the incoming ping. Ilara would want to hear how the session had gone, would check that she was on her way home for dinner. But Leda wasn’t ready for that kind of forced, upbeat normalcy right now. She needed a moment to herself, to quiet the thoughts and regrets chasing one another in a wild tumult through her head.

She stepped onto the local C lift and disembarked a few stops upTower. Soon she was standing before an enormous stone archway, which had been transported stone by stone from some old British university, carved with enormous block letters that read THE BERKELEY SCHOOL.

Leda breathed a sigh of relief as she walked through the arch and her contacts automatically shut off. Before Eris’s death, she’d never realized how grateful she might feel for her high school’s tech-net.

Her footsteps echoed in the silent halls. It was sort of eerie here at night, everything cast in dim, bluish-gray shadows. She moved faster, past the lily pond and athletic complex, all the way to the blue door at the edge of campus. Normally this room was locked after hours, but Leda had schoolwide access thanks to her position on student council. She stepped forward, letting the security system register her retinas, and the door swung obediently inward.

She hadn’t been in the Observatory since her astronomy elective last spring. Yet it looked exactly as she remembered: a vast circular room lined with telescopes, high-resolution screens, and cluttered data processors Leda had never learned to use. A geodesic dome soared overhead. And in the center of the floor lay the pièce de résistance: a glittering patch of night.

The Observatory was one of the few places in the Tower that protruded out past the floor below it. Leda had never understood how the school had gotten the zoning permits for it, but she was glad now that they had, because it meant they could build the Oval Eye: a concave oval in the floor, about three meters long and two meters wide, made of triple-reinforced flexiglass. A glimpse of how high they really were, up here near the top of the Tower.

Leda edged closer to the Oval Eye. It was dark down there, nothing but shadows, and a few stray lights bobbing in what she thought were the public gardens on the fiftieth floor. What the hell, she thought wildly, and stepped out onto the flexiglass.

This sort of behavior was definitely off-limits, but Leda knew the structure would support her. She glanced down. Between her ballet flats was nothing but empty air, the impossible, endless space between her and the laminous darkness far below. This is what Eris saw when I pushed her, Leda thought, and despised herself.

She sank down, not caring that there was nothing protecting her from a two-mile fall except a few layers of fused carbon. Pulling her knees to her chest, she lowered her forehead and closed her eyes.

A shaft of light sliced into the room. Leda’s head shot up in panic. No one else had access to the Observatory except the rest of the student council, and the astronomy professors. What would she say to explain herself?

“Leda?”

Her heart sank as she realized who it was. “What are you doing here, Avery?”

“Same thing as you, I guess.”

Leda felt caught off guard. She hadn’t been alone with Avery since that night—when Leda confronted Avery about being with Atlas, and Avery led her up onto the roof, and everything spun violently out of control. She wanted desperately to say something, but her mind had strangely frozen. What could she say, with all the secrets she and Avery had made together, buried together?

After a moment, Leda was shocked to hear footsteps approaching, as Avery walked over to sit on the opposite edge of the Oval.