Полная версия

Journey to Jo’Burg

Copyright

First published in Great Britain by Longman Group Ltd 1985

First published by Collins 1987

This edition published by HarperCollins Children’s Books 2016 HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd, 1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

The HarperCollins Children’s Books website address is

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Copyright © Beverley Naidoo/Canon Collins Educational Trust for South Africa 1985

Illustration copyright © Lisa Kopper

Note from the author copyright © Beverley Naidoo 1999

Why You’ll Love This Book copyright © Michael Rosen 2008

Journey to Jo’burg is published by arrangement with Longman Group Ltd, London

Cover design © HarperCollins Publishers 2016

Cover illustration © Andy Bridge 2016

Beverley Naidoo and Lisa Kopper assert the moral right to be identified as the author and illustrator of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007263509

Ebook Edition © 2016 ISBN: 9780007368853

Version: 2016-07-22

In memory of two small children who died far away from their mother … and to Kentse Mary Sebate, their Mma, who worked in Jo’burg.

Why You’ll Love This Book By Michael Rosen

The history of children’s books is full of wonderful and extraordinary stories, but it has to be said that a great majority of these are about one tiny, narrow band of the human race: middle-class western European and American people. Of course, our massively popular folk tales talk of peoples struggling to survive – think Hansel and Gretel, for example – but once novels for children started to be written, the authors tended to write about people like themselves. This is not a complaint – I do it myself! However, when a book comes in front of us that does that rare thing of talking of people with a way of life utterly distant from this western European type, it’s my view that we should celebrate it.

When Beverley Naidoo wrote Journey to Jo’burg, South Africa was a place that had a very special kind of political structure:it was ruled by a white elite that had its origins in two countries – Britain and Holland. So, the two languages of those who ruled were English and a form of Dutch called Afrikaans. There was also a big minority of people of Eastern European Jewish origin, they tended to speak English rather than Afrikaans. But the large majority of people living under this rule came from the many nations of Africans – people like the Tswana and the Zulus – who had been living on the continent of Africa long before the British or Dutch had come to settle and rule there. The system of rule was called Apartheid, an Afrikaans word meaning something like “separateness”. However, this makes Apartheid sound as if it was just a matter of living separately; it was far from it. It meant something much more stark and cruel: the white people of European origin were the only ones who benefited from the system. They invented hundreds of rules that tried to ensure that white people and black people were kept apart. This meant that there were many places – like the best swimming pools, shops, schools and colleges – where black people were not allowed to go. But in the end it was Apartheid itself that fell apart! Nelson Mandela who had fought against the system was released from prison and the black people of South Africa won the right to vote.

So, Journey to Jo’burg has become a different kind of book. When Beverley wrote it, it was a book that threw light on a problem that was going on at that very moment. I can remember the feeling that teachers, writers and school students had: this was a story about now, and spoke out on behalf of the people suffering in South Africa. We had read, heard or seen musicians, poets and plays that had spoken like this, but we had never thought there could be a children’s book that talked of such things. And yet here it was. For some of us who supported Nelson Mandela and what was called the “Anti-Apartheid” movement, this was very exciting.

Of course, some people said that children’s books shouldn’t be “political”, or that they shouldn’t “preach” or try to put over a “message”. Well, the only problem with this argument is that one of the most popular children’s books, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, is a very political book and does put over a “message”. What’s more, all through Victorian times, many, many children’s books, comics and magazines put over strong messages about how children should behave. Indeed, lots of popular stories also spoke about how it was right and proper for British people to rule in Africa. So, in some ways, I see Beverley’s book almost as a reply to those kinds of books and magazine stories that I used to read when I was a boy, books that told me that I was civilised and sensible, and African people were dangerous or childish.

Now Journey to Jo’burg has become what we would call a “historical novel”. It’s about a time and a society that has passed away. So, why bother to read it? Hasn’t that urgency and excitement disappeared? Well, there are several answers to this. First of all, we never tire of hearing about times from the past. This comes to us in all sorts of ways – through finding out about our own families, through history programmes on the TV, books and even films set in past times like Gladiator or Beowulf. And of course we can read books or see films that were, in their day, set in their own time, but are now history – like books by Charles Dickens, plays by Shakespeare and the like. All this suggests to me that most of us like trying to feel and understand what it was like in another time, in another place. Perhaps we want to compare it to how we live now. But what is especially special about Journey to Jo’burg is that it’s not only set in a society that has changed, but that it’s about the people who were the most poor in that society. And another thing: these poor people wouldn’t be “saved” by clever, nice, rich people. They struggled to get something better by themselves.

There’s another reason why the book is worth reading. Though Apartheid is finished, there are places all over the world where something similar is going on. A group of people rule a country for their own benefit and the poor people have very few rights – there are places they are not allowed to go, or certain kinds of mixing that are not allowed. When Beverley wrote Journey to Jo’burg, no one knew if Apartheid would be defeated. When she wrote it, for all she or anyone else knew, the system might last for ten, twenty or a hundred years more. But now, we know that it was defeated, and in its own way, this book helped in that. One thing that the rulers of South Africa hated was people around the world knowing how black African people were living. The book was of course banned in South Africa itself. If anyone tried to bring copies of it into the country, customs people seized and destroyed them. That’s how dangerous it was considered to be!

So, when we read the book today, we are reminded of the struggles that people had to face in South Africa during an oppressive and unfair system, and that in the end their fight for freedom was successful. But more than that, this book can help us think about other people living in brutal and controlling conditions, and how for them too, we can hope that it won’t last much longer.

Michael Rosen

Michael Rosen is well known as a poet and broadcaster, his work has won numerous awards, including the Nestle Smarties Prize for We’re Going On a Bear Hunt. He has devoted his life to entertaining children with his writing and performances and to informing teachers, librarians, parents, publishers and government agencies of the importance of supporting children’s books. Michael’s contribution to the world of children’s books was recognised in 2007 when he was appointed the Children’s Laureate.

***

Can you imagine having to live apart from your parents for most of your childhood?

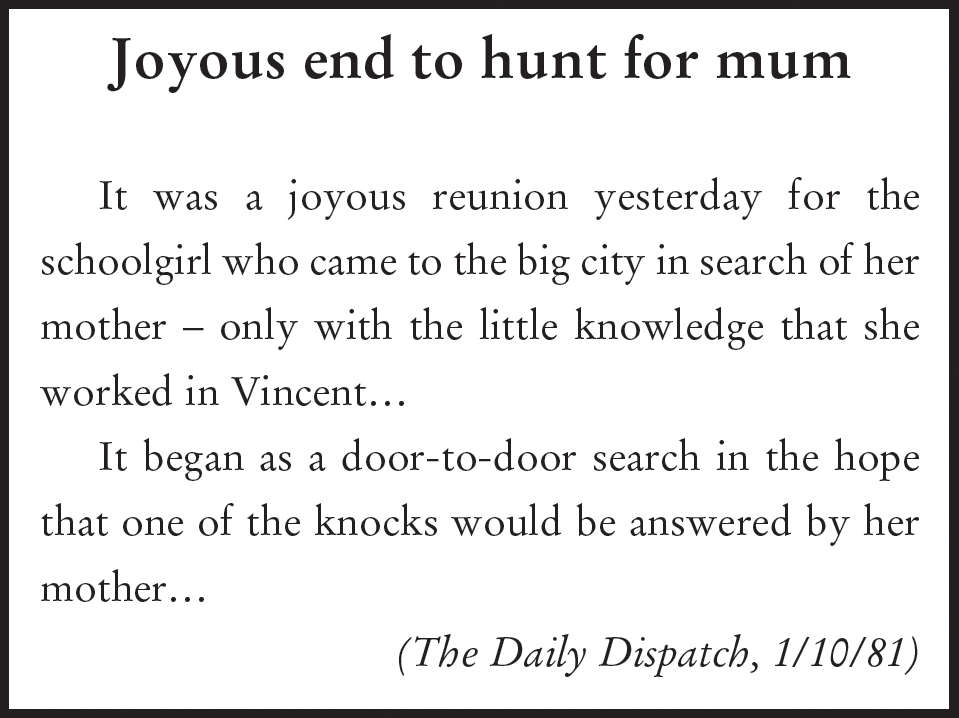

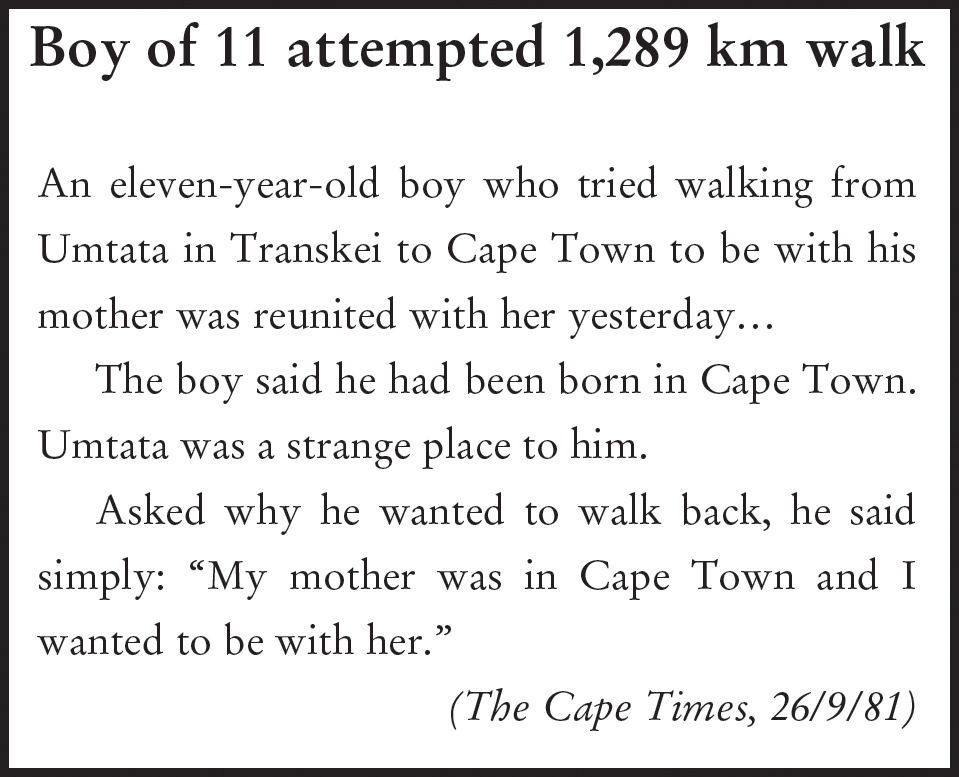

In South Africa for a long time the law forced many parents and children apart. Many fathers and mothers from the countryside had to go away to towns and cities to work. Their children had to stay behind. For this was the land of apartheid – where the broken families were all black and the people who made the laws were white. We didn’t often hear about the children who were cut off from their parents. We only got a glimpse of them through a short news item now and then.

Another report told of a boy who had always lived with his mother until he was caught up in a police raid and taken hundreds of miles away.

It will take a long time to repair the damage of apartheid. Journey to Jo’burg may help you understand why. But many people have planted their hopes, like seeds. now they need to work hard at helping them grow.

***

Map

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Why You’ll Love This Book By Michael Rosen

Map

Chapter One – Naledi’s Plan

Chapter Two – The Road

Chapter Three – Oranges!

Chapter Four – Ride on a Lorry

Chapter Five – The City of Gold

Chapter Six – A New Friend

Chapter Seven – Mma

Chapter Eight – Police

Chapter Nine – The Photograph

Chapter Ten – Grace’s Story

Chapter Eleven – Journey Home

Chapter Twelve – The Hospital

Chapter Thirteen – Life and Death

Chapter Fourteen – Waiting

Chapter Fifteen – Hope

Footnotes

More than a Story

About the Author

Also by the same author

About the Publisher

Chapter One

NALEDI’S PLAN

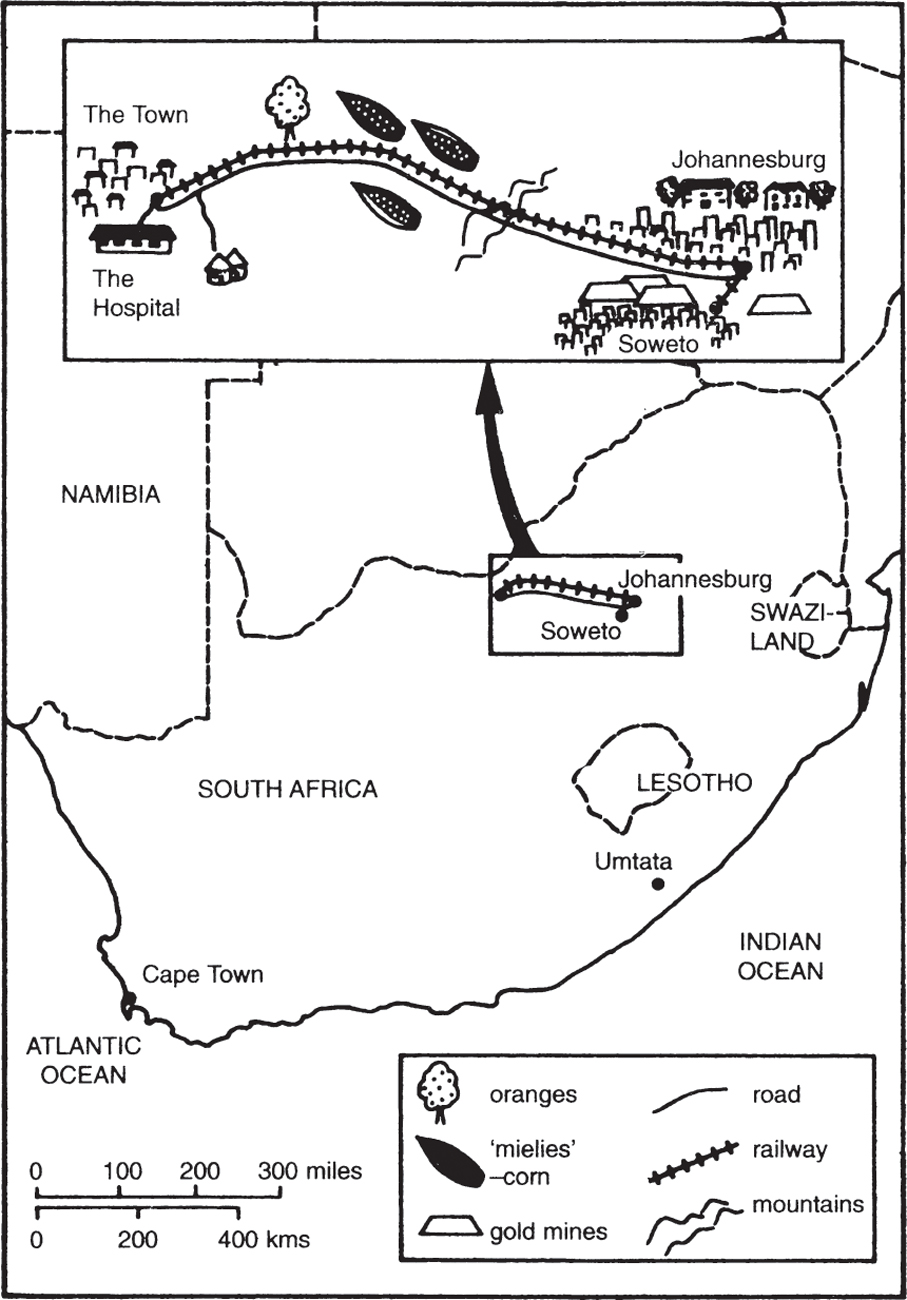

Naledi and Tiro were worried. Their baby sister Dineo was ill, very ill. For three days now, Nono their granny had been trying to cool her fever with damp cloths placed on her little head and body. Mmangwane1, their aunty, made her take sips of water, but still their sister lay hot and restless, crying softly at times.

“Can’t we take Dineo to the hospital?” Naledi begged, but Nono said Dineo was much too sick to be carried that far. The only hospital was many miles away, and Naledi also knew they had no money to pay a doctor to visit them. No one in the village had that much money.

“If only Mma2 was here,” Naledi wished over and over as she and Tiro walked down to the village tap with their empty buckets. She clutched tightly at the coins in her hand.

Each morning the children had to pass the place of graves on their way to buy the day’s water and only last week another baby in the village had died. It was always scary seeing the little graves, but especially this fresh one now.

As they came nearer, Naledi fixed her eyes on the ground ahead, trying not to look, trying not to think. But it was no use. She just couldn’t stop herself thinking of her own little sister being lowered into a hole in the ground.

Finally Naledi could stand it no longer. When they had returned with the water, she called Tiro to the back of the house and spoke bluntly.

“We must get Mma, or Dineo is going to die!”

“But how?” Tiro was bewildered. Their mother worked and lived in Johannesburg, more than 300 kilometres away.

“We can get to the big road and walk,” Naledi replied calmly.

It was the school holidays now, but in term-time it took the children more than an hour to walk to school each day, so they were used to walking. Naledi wasn’t going to let herself think how much longer it would take to get to Johannesburg.

However, Tiro was not so sure.

“But Nono doesn’t want us to worry Mma and I know she won’t let us go!”

“That’s just it,” Naledi retorted quickly. “Nono and Mmangwane keep saying Dineo will be better soon. You heard them talking last night. They say they don’t want to send Mma a telegram and frighten her. But what if they wait and it’s too late?”

Tiro thought for a moment.

“Can’t we send Mma a telegram?”

“How can we if we haven’t the money? And if we borrow some, Nono will hear about it and be very cross with us.”

It was clear that Naledi had made up her mind – and Tiro knew his sister. She was four years older than him, already thirteen, and once she had decided something, that was that.

So Tiro gave up reasoning.

The children went to find Naledi’s friend Poleng, and explained. Poleng was very surprised but agreed to help. She would tell Nono once the children had gone and she also promised to help their granny, bringing the water and doing the other jobs.

“How will you eat on the way?” Poleng asked.

Tiro looked worried, but Naledi was confident.

“Oh, we’ll find something.”

Poleng told them to wait and ran into her house, returning soon with a couple of sweet potatoes and a bottle of water. The children thanked her. She was indeed a good friend.

Before they could go, Naledi had to get the last letter Mma had sent, so they would know where to look for her in the big city. Slipping into the house, Naledi took the letter quietly from the tin without Nono or Mmangwane noticing. Both were busy with Dineo as Naledi slipped out again.

Chapter Two

THE ROAD

The children walked quickly away from the village. The road was really just a track made by car tyres. Two lines of dusty red earth leading out across the flat dry grassland.

Once at the big tar road, they turned in the direction of the early morning sun, for that was the way to Johannesburg. The steel railway line glinted alongside the road.

“If only we had some money to buy tickets for the train. We don’t have even one cent.” Tiro sighed.

“Never mind. We’ll get there somehow!” Naledi was still confident as they set off eastwards.

The tar road burnt their feet.

“Let’s walk at the side,” Tiro suggested.

The grass was dry and scratchy, but they were used to it. Now and again, a car or a truck roared by, and then the road was quiet again and they were alone. Naledi began to sing the words of her favourite tune and Tiro was soon joining in.

On they walked.

“Can’t we stop and eat?” Tiro was beginning to feel sharp stabs of hunger. But Naledi wanted to go on until they reached the top of the long, low hill ahead.

Their legs slowed down as they began the walk uphill, their bodies feeling heavy. At last they came to the top and flopped down to rest.

Hungrily they ate their sweet potatoes and drank the water. The air was hot and still. Some birds skimmed lightly across the sky as they gazed down at the long road ahead. It stretched into the distance, between fenced-off fields and dry grass, up to another far-off hill.

“Come on! We must get on,” Naledi insisted, pulling herself up quickly.

She could tell that Tiro was already tired, but they couldn’t afford to stop for long. The sun had already passed its midday position and they didn’t seem to have travelled very far.

On they walked, steadily, singing to break the silence.

But in the middle of the afternoon, when the road led into a small town, they stopped singing and began to walk a little faster. They were afraid a policeman might stop them because they were strangers.

Policemen were dangerous. Even in their village they knew that …

The older children at school had made up a song:

“Beware that policeman,

He’ll want to see your ‘pass’1,

He’ll say it’s not in order,

That day may be your last!”

Grown-ups were always talking about this “pass”. If you wanted to visit some place, the “pass” must allow it. If you wanted to change your job, the “pass” must allow it. It seemed everyone in school knew somebody who had been in trouble over the “pass”.

Naledi and Tiro remembered all too clearly the terrible stories their uncle had told them about a prison farm. One day he had left his “pass” at home and a policeman had stopped him. That was how he got sent to the prison farm.

So, without even speaking, Naledi and Tiro knew the fear in the other’s heart as they walked through the strange town. They longed to look in some of the shop windows, but they did not dare stop. Nervously, they hurried along the main street, until they had left the last house of the town behind them.

Chapter Three

ORANGES

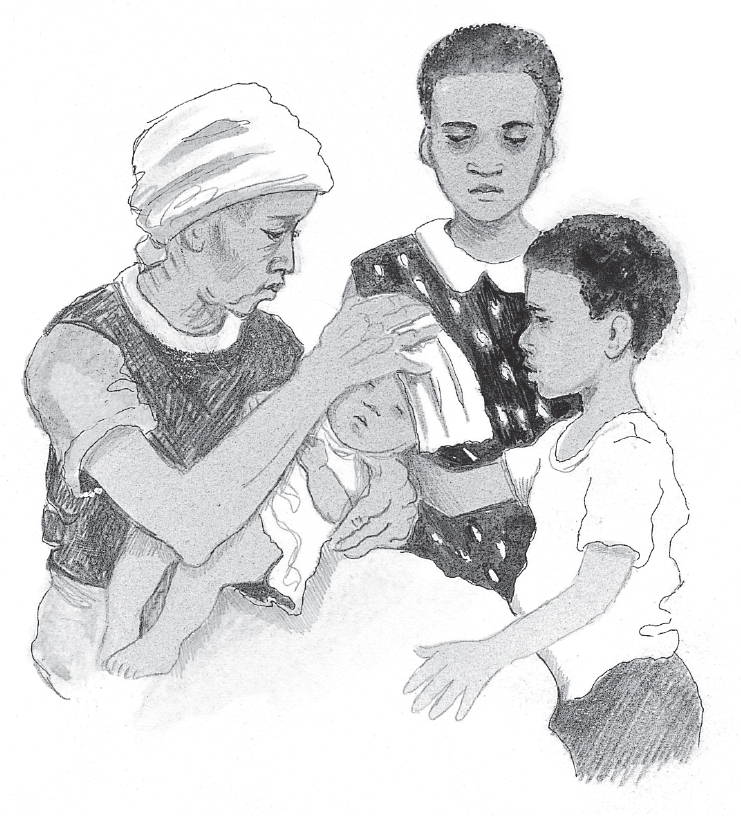

On they walked. The sun was low down now and there was a strong smell of oranges coming from rows and rows of orange trees behind barbed wire fences. As far as they could see there were orange trees with dark green leaves and bright round fruit. Oranges were sweet and wonderful to taste and they didn’t have them often.

The children looked at each other.

“Do you think we could …” Tiro began.

But Naledi was already carefully pushing apart the barbed wire, edging her body through.

“Keep watch!” she ordered Tiro.

She was on tiptoes, stretching for an orange, when they heard, “HEY, YOU!”

Naledi dropped down, then dashed for the fence. Tiro was holding the wires for her. She tried to scramble through, but it was too late. A hand grasped her and pulled her back.

Naledi looked up and saw a young boy, her own age.

“What are you doing?” he demanded.

He spoke in Tswana, their own language.

“The white farmer could kill you if he sees you. Don’t you know he has a gun to shoot thieves?”

“We’re not thieves. We’ve been walking all day and we’re very hungry. Please don’t call him,” Naledi pleaded.

The boy looked more friendly now and asked where they came from.

So they told him about Dineo and how they were going to Johannesburg. The boy whistled.

“Phew. So far!”

He paused.

“Look. I know a place where you can sleep tonight and where the farmer won’t find you. Stay here and I’ll take you there when it’s dark.”

Naledi and Tiro glanced at each other, still a little nervous.

“Don’t worry. You’ll be safe waiting here. The farmer has gone inside for his supper,” the boy reassured them. Then he grinned. “But if you eat oranges you must hide the peels well or there will be big trouble. We have to pick the fruit, but we’re not allowed to eat it.”

He turned and ran off, calling softly, “See you later.”

“Can we stay here for the night?” Tiro asked.

Naledi wasn’t too sure if they should.

“It can go badly if the farmer finds us. Remember what happened to Poleng’s brother?”

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.