Полная версия

Paddington Complete Novels

“Go away!” said a booming voice. “I don’t want to see anyone.”

Paddington peered round the door. Sir Sealy Bloom was lying stretched out on a long couch. He looked tired and cross. He opened one eye and gazed at Paddington.

“I’m not signing any autographs,” he growled.

“I don’t want your autograph,” said Paddington, fixing him with a hard stare. “I wouldn’t want your autograph if I had my autograph book, and I haven’t got my autograph book so there!”

Sir Sealy sat up. “You don’t want my autograph?” he said, in a surprised voice. “But everyone always wants my autograph!”

“Well, I don’t,” said Paddington. “I’ve come to tell you to take your daughter back!” He gulped the last few words. The great man seemed to have grown to about twice the size he had been on the stage, and he looked as if he was going to explode at any minute.

Sir Sealy clutched his forehead. “You want me to take my daughter back?” he said at last.

“That’s right,” said Paddington, firmly. “And if you don’t, I expect she can come and stay with Mr and Mrs Brown.”

Sir Sealy Bloom ran his hand distractedly through his hair and then pinched himself. “Mr and Mrs Brown,” he repeated in a dazed voice. He looked wildly round the room and then dashed to the door. “Sarah!” he called, in a loud voice. “Sarah, come in here at once!” He backed round the room until he had placed the couch between himself and Paddington. “Keep away, bear!” he said, dramatically, and then peered at Paddington, for he was rather short-sighted. “You are a bear, aren’t you?” he added.

“That’s right,” said Paddington. “From Darkest Peru!”

Sir Sealy looked at his woollen hat. “Well then,” he said crossly, playing for time, “you ought to know better than to wear a green hat in my dressing-room. Don’t you know green is a very unlucky colour in the theatre? Take it off at once.”

“It’s not my fault,” said Paddington. “I wanted to wear my proper hat.” He had just started to explain all about his hat when the door burst open and the lady called Sarah entered. Paddington immediately recognised her as Sir Sealy’s daughter in the play.

“It’s all right,” he said. “I’ve come to rescue you.”

“You’ve what?” The lady seemed most surprised.

“Sarah,” Sir Sealy Bloom came out from behind the couch. “Sarah, protect me from this… this mad bear!”

“I’m not mad,” said Paddington, indignantly.

“Then kindly explain what you are doing in my dressing-room,” boomed the great actor.

Paddington sighed. Sometimes people were very slow to understand things. Patiently he explained it all to them. When he had finished, the lady called Sarah threw back her head and laughed.

“I’m glad you think it’s funny,” said Sir Sealy.

“But darling, don’t you see?” she said. “It’s a great compliment. Paddington really believes you were throwing me out into the world without a penny. It shows what a great actor you are!”

Sir Sealy thought for a moment. “Humph!” he said, gruffly. “Quite an understandable mistake, I suppose. He looks a remarkably intelligent bear, come to think of it.”

Paddington looked from one to the other. “Then you were only acting all the time,” he faltered.

The lady bent down and took his paw. “Of course, darling. But it was very kind of you to come to my rescue. I shall always remember it.”

“Well, I would have rescued you if you’d wanted it,” said Paddington.

Sir Sealy coughed. “Are you interested in the theatre, bear?” he boomed.

“Oh, yes,” said Paddington. “Very much. Except I don’t like having to pay so much for everything. I want to be an actor when I grow up.”

The lady called Sarah jumped up. “Why, Sealy darling,” she said, looking at Paddington. “I’ve an idea!” She whispered in Sir Sealy’s ear and then Sir Sealy looked at Paddington. “It’s a bit unusual,” he said, thoughtfully. “But it’s worth a try. Yes, it’s certainly worth a try!”

In the theatre itself the interval was almost at an end and the Browns were getting restless.

“Oh, dear,” said Mrs Brown. “I wonder where he’s got to?”

“If he doesn’t hurry up,” said Mr Brown, “he’s going to miss the start of the second act.”

Just then there was a knock at the door and an attendant handed him a note. “A young bear gentleman asked me to give you this,” he announced. “He said it was very urgent.”

“Er… thank you,” said Mr Brown, taking the note and opening it.

“What does it say?” asked Mrs Brown, anxiously. “Is he all right?”

Mr Brown handed her the note to read. “Your guess is as good as mine,” he said.

Mrs Brown looked at it. It was hastily written in pencil and it said: I HAVE BEEN GIVEN A VERRY IMPORTANT JOB. PADINGTUN. P.S. I WILL TEL YOU ABOUT IT LAYTER.

“Now what on earth can that mean?” she said. “Trust something unusual to happen to Paddington.”

“I don’t know,” said Mr Brown, settling back in his chair as the lights went down. “But I’m not going to let it spoil the play.”

“I hope the second half is better than the first,” said Jonathan. “I thought the first half was rotten. That man kept on forgetting his lines.”

The second half was much better than the first. From the moment Sir Sealy strode on to the stage the theatre was electrified. A great change had come over him. He no longer fumbled over his lines, and people who had coughed all through the first half now sat up in their seats and hung on his every word.

When the curtain finally came down on the end of the play, with Sir Sealy’s daughter returning to his arms, there was a great burst of applause. The curtain rose again and the whole company bowed to the audience. Then it rose while Sir Sealy and Sarah bowed, but still the cheering went on. Finally Sir Sealy stepped forward and raised his hand for quiet.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” he said. “Thank you for your kind applause. We are indeed most grateful. But before you leave I would like to introduce the youngest and most important member of our company. A young… er, bear, who came to our rescue…” The rest of Sir Sealy’s speech was drowned in a buzz of excitement as he stepped forward to the very front of the stage, where a small screen hid a hole in the boards which was the prompt box.

He took hold of one of Paddington’s paws and pulled. Paddington’s head appeared through the hole. In his other paw he was grasping a copy of the script.

“Come along, Paddington,” said Sir Sealy. “Come and take your bow.”

“I can’t,” gasped Paddington. “I think I’m stuck!”

And stuck he was. It took several stagehands, the fireman, and a lot of butter to remove him after the audience had gone. But he was far enough out to twist round and raise his hat to the cheering crowd before the curtain came down for the last time.

Several nights later, anyone going into Paddington’s room would have found him sitting up in bed with his scrapbook, a pair of scissors, and a pot of paste. He was busy pasting in a picture of Sir Sealy Bloom, which the great man had signed: ‘To Paddington, with grateful thanks.’ There was also a signed picture from the lady called Sarah, and one of his proudest possessions – a newspaper cutting about the play headed PADDINGTON SAVES THE DAY!

Mr Gruber had told him that the photographs were probably worth a bit of money, but after much thought he had decided not to part with them. In any case, Sir Sealy Bloom had given him his twenty pence back and a pair of opera glasses.

ONE MORNING MR Brown tapped the barometer in the hall. “It looks as if it’s going to be a nice day,” he said. “How about a trip to the sea?”

His remark was greeted with enthusiasm by the rest of the family, and in no time at all the house was in an uproar.

Mrs Bird started to cut a huge pile of sandwiches while Mr Brown got the car ready. Jonathan and Judy searched for their bathing suits and Paddington went up to his room to pack. An outing which involved Paddington was always rather a business, as he insisted on taking all his things with him. As time went by he had acquired lots of things. As well as his suitcase, he now had a smart weekend grip with the initials P.B. inscribed on the side and a paper carrier-bag for the odds and ends.

For the summer months Mrs Brown had bought him a sun hat. It was made of straw and very floppy. Paddington liked it, for by turning the brim up or down, he could make it different shapes, and it was really like having several hats in one.

“When we get to Brightsea,” said Mrs Brown, “we’ll buy you a bucket and spade. Then you can make a sand-castle.”

“And you can go to the pier,” said Jonathan, eagerly. “They’ve some super machines on the pier. You’d better bring plenty of coins.”

“And we can go swimming,” added Judy. “You can swim, can’t you?”

“Not very well, I’m afraid,” replied Paddington. “You see, I’ve never been to the seaside before!”

“Never been to the seaside!” Everyone stopped what they were doing and stared at Paddington.

“Never,” said Paddington.

They all agreed that it must be nice to be going to the seaside for the first time in one’s life; even Mrs Bird began talking about the time she first went to Brightsea, many years before. Paddington became very excited as they told him all about the wonderful things he was going to see.

The car was crowded when they started off. Mrs Bird, Judy, and Jonathan sat in the back. Mr Brown drove and Mrs Brown and Paddington sat beside him. Paddington liked sitting in the front, especially when the window was open, so that he could poke his head out in the cool breeze. After a minor delay when Paddington’s hat blew off on the outskirts of London, they were soon on the open road.

“Can you smell the sea yet, Paddington?” asked Mrs Brown after a while.

Paddington poked his head out and sniffed. “I can smell something,” he said.

“Well,” said Mr Brown. “Keep on sniffing, because we’re almost there.” And sure enough, as they reached the top of a hill and rounded a corner to go down the other side, there it was in the distance, glistening in the morning sun.

Paddington’s eyes opened wide. “Look at all the boats on the dirt!” he cried, pointing in the direction of the beach with his paw.

Everyone laughed. “That’s not dirt,” said Judy. “That’s sand.” By the time they had explained all about sand to Paddington they were in Brightsea itself, and driving along the front. Paddington looked at the sea rather doubtfully. The waves were much bigger than he had imagined. Not so big as the ones he’d seen on his journey to England, but quite large enough for a small bear.

Mr Brown stopped the car by a shop on the esplanade and took out some money. “I’d like to fit this bear out for a day at the seaside,” he said to the lady behind the counter. “Let’s see now, we shall need a bucket and spade, a pair of sunglasses, one of those rubber tyres…” As he reeled off the list, the lady handed the articles to Paddington, who began to wish he had more than two paws. He had a rubber tyre round his middle which kept slipping down around his knees, a pair of sunglasses perched precariously on his nose, his straw hat, a bucket and spade in one hand, and his suitcase in the other.

“Photograph, sir?” Paddington turned to see an untidy man with a camera looking at him. “Only one pound, sir. Results guaranteed. Money back if you’re not satisfied.”

Paddington considered the matter for a moment. He didn’t like the look of the man very much, but he had been saving hard for several weeks and now had just over three pounds. It would be nice to have a picture of himself.

“Won’t take a minute, sir,” said the man, disappearing behind a black cloth at the back of the camera. “Just watch the birdie.”

Paddington looked around. There was no bird in sight as far as he could see. He went round behind the man and tapped him. The photographer, who appeared to be looking for something, jumped and then emerged from under his cloth. “How do you expect me to take your picture if you don’t stand in front?” he asked in an aggrieved voice. “Now I’ve wasted a plate, and” – he looked shiftily at Paddington – “that will cost you one pound!”

Paddington gave him a hard stare. “You said there was a bird,” he said. “And there wasn’t.”

“I expect it flew away when it saw your face,” said the man nastily. “Now where’s my pound?”

Paddington looked at him even harder for a moment. “Perhaps the bird took it when it flew away,” he said.

“Ha! Ha! Ha!” cried another photographer, who had been watching the proceedings with interest. “Fancy you being taken in by a bear, Charlie! Serves you right for trying to take photographs without a licence. Now be off with you before I call a policeman.”

He watched while the other man gathered up his belongings and slouched off in the direction of the pier, then he turned to Paddington. “These people are a nuisance,” he said. “Taking away the living from honest folk. You did quite right not to pay him any money. And if you’ll allow me, I’d like to take a nice picture of you myself, as a reward!”

The Brown family exchanged glances. “I don’t know,” said Mrs Brown. “Paddington always seems to fall on his feet.”

“That’s because he’s a bear,” said Mrs Bird darkly. “Bears always fall on their feet.” She led the way on to the beach and carefully laid out a travelling rug on the sand behind a breakwater. “This will be as good a spot as any,” she said. “Then we shall all know where to come back to, and no one will get lost.”

“The tide’s out,” said Mr Brown. “So it will be nice and safe for bathing.” He turned to Paddington. “Are you going in, Paddington?” he asked.

Paddington looked at the sea. “I might go for a paddle,” he said.

“Well, hurry up,” called Judy. “And bring your bucket and spade, then we can practise making sand-castles.”

“Gosh!” Jonathan pointed to a notice pinned on the wall behind them. “Look… there’s a sand-castle competition. Whizzo! First prize ten pounds for the biggest sand-castle!”

“Suppose we all join in and make one,” said Judy. “I bet the three of us together could make the biggest one you’ve ever seen.”

“I don’t think you’re allowed to,” said Mrs Brown, reading the notice. “It says here everyone has to make their own.”

Judy looked disappointed. “Well, I shall have a go, anyway. Come on, you two, let’s have a bathe first, then we can start digging after lunch.” She raced down the sand closely followed by Jonathan and Paddington. At least, Jonathan followed but Paddington only got a few yards before his life-belt slipped down and he went headlong in the sand.

“Paddington, do give me your suitcase,” called Mrs Brown. “You can’t take it in the sea with you. It’ll get wet and be ruined.”

Looking rather crestfallen, Paddington handed his things to Mrs Brown for safekeeping and then ran down the beach after the others. Judy and Jonathan were already a long way out when he got there, so he contented himself with sitting on the water’s edge for a while, letting the waves swirl around him as they came in. It was a nice feeling, a bit cold at first, but he soon got warm. He decided the seaside was a nice place to be. He paddled out to where the water was deeper and then lay back in his rubber tyre, letting the waves carry him gently back to the shore.

“Ten pounds! Supposing… supposing he won ten whole pounds!” He closed his eyes. In his mind he had a picture of a beautiful castle made of sand, like the one he’d once seen in a picture-book, with battlements and towers and a moat. It was getting bigger and bigger and everyone else on the beach had stopped to gather round and cheer. Several people said they had never seen such a big sand-castle, and… he woke with a start as he felt someone splashing water on him.

“Come on, Paddington,” said Judy. “Lying there in the sun fast asleep. It’s time for lunch, and we’ve got lots of work to do afterwards.” Paddington felt disappointed. It had been a nice sand-castle in his dream. He was sure it would have won first prize. He rubbed his eyes and followed Judy and Jonathan up the beach to where Mrs Bird had laid out the sandwiches – ham, egg, and cheese for everyone else, and special marmalade ones for Paddington – with ice-cream and fruit salad to follow.

“I vote,” said Mr Brown, who had in mind an after-lunch nap for himself, “that after we’ve eaten you all go off in different directions and make your own sand-castles. Then we’ll have our own private competition as well as the official one. I’ll give a pound to the one with the biggest castle.”

All three thought this was a good idea. “But don’t go too far away,” called Mrs Brown, as Jonathan, Judy and Paddington set off. “Remember the tide’s coming in!” Her advice fell on deaf ears; they were all much too interested in sand-castles. Paddington especially was gripping his bucket and spade in a very determined fashion.

The beach was crowded and he had to walk quite a long way before he found a deserted spot. First of all he dug a big moat in a circle, leaving himself a drawbridge so that he could fetch and carry the sand for the castle itself. Then he set to work carrying bucketloads of sand to build the walls of the castle.

He was an industrious bear and even though it was hard work and his legs and paws soon got tired, he persevered until he had a huge pile of sand in the middle of his circle. Then he set to work with his spade, smoothing out the walls and making the battlements. They were very good battlements, with holes for windows and slots for the archers to fire through.

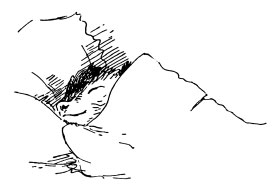

When he had finished he stuck his spade in one of the corner towers, placed his hat on top of that, and then lay down inside next to his marmalade jar and closed his eyes. He felt tired, but very pleased with himself. With the gentle roar of the sea in his ears he soon went fast asleep.

“We’ve been all along the beach,” said Jonathan. “And we can’t see him anywhere.”

“He didn’t even have his life-belt with him,” said Mrs Brown anxiously. “Nothing. Just a bucket and spade.” The Browns were gathered in a worried group round the man from the lifesaving hut.

“He’s been gone several hours,” said Mr Brown. “And the tide’s been in over two!”

The man looked serious. “And you say he can’t swim?” he asked.

“He doesn’t even like having a bath much,” said Judy. “So I’m sure he can’t swim.”

“Here’s his photograph,” said Mrs Bird. “He only had it taken this morning.” She handed the man Paddington’s picture and then dabbed her eyes with a handkerchief. “I know something’s happened to him. He wouldn’t have missed tea unless something was wrong.”

The man looked at the picture. “We could send out a description,” he said, dubiously. “But it’s a job to see what he looks like by that. It’s all hat and dark glasses.”

“Can’t you launch a lifeboat?” asked Jonathan, hopefully.

“We could,” said the man. “If we knew where to look. But he might be anywhere.”

“Oh, dear,” Mrs Brown reached for her handkerchief as well. “I can’t bear to think about it.”

“Something will turn up,” said Mrs Bird, comfortingly.”He’s got a good head on his shoulders.”

“Well,” said the man, holding up a dripping straw hat. “You’d better have this, and in the meantime… we’ll see what we can do.”

“There, there, Mary!” Mr Brown held his wife’s arm. “Perhaps he just left it on the beach or something. It may have got picked up by the tide.” He bent down to pick up the rest of Paddington’s belongings. They seemed very small and lonely, lying there on their own.

“It’s Paddington’s hat all right,” said Judy, examining it. “Look – it’s got his mark inside!” She turned the hat inside out and showed them the outline of a paw mark in black ink and the words MY HAT – PADINGTUN.

“I vote we all separate,” said Jonathan, “and comb the beach. We’ll stand more chance that way.”

Mr Brown looked dubious. “It’s getting dark,” he said.

Mrs Bird put down the travelling rug and folded her arms. “Well, I’m not going back until he’s found,” she said. “I couldn’t go back to that empty house – not without Paddington.”

“No one’s thinking of going back without him, Mrs Bird,” said Mr Brown. He looked helplessly out to sea. “It’s just…”

“P’raps he didn’t get swep’ out to sea,” said the lifesaving man, helpfully. “P’raps he’s just gone on the pier or something. There seems to be a big crowd heading that way. Must be something interesting going on.” He called out to a man who was just passing. “What’s going on at the pier, chum?”

Without stopping, the man looked back over his shoulder and shouted, “Chap just crossed the Atlantic all by ’isself on a raft. ’Undreds of days without food or water so they say!” He hurried on.

The lifesaving man looked disappointed. “Another of these publicity stunts,” he said. “We get ’em every year.”

Mr Brown looked thoughtful. “I wonder,” he said, looking in the direction of the pier.

“It would be just like him,” said Mrs Bird. “It’s the sort of thing that would happen to Paddington.”

“It’s got to be!” cried Jonathan. “It’s just got to be!”

They all looked at each other and then, picking up their belongings, joined the crowd hurrying in the direction of the pier. It took them a long time to force their way through the turnstile, for the news that ‘something was happening on the pier’ had spread and there was a great throng at the entrance. But eventually, after Mr Brown had spoken to a policeman, a way was made for them and they were escorted to the very end, where the paddle-steamers normally tied up.

A strange sight met their eyes. Paddington, who had just been pulled out of the water by a fisherman, was sitting on his upturned bucket talking to some reporters. Several of them were taking photographs while the rest fired questions at him.

“Have you come all the way from America?” asked one reporter.

The Browns, hardly knowing whether to laugh or cry, waited eagerly for Paddington’s reply.

“Well, no,” said Paddington, truthfully, after a moment’s pause. “Not America. But I’ve come a long way.” He waved a paw vaguely in the direction of the sea. “I got caught by the tide, you know.”

“And you sat in that bucket all the time?” asked another man, taking a picture.

“That’s right,” replied Paddington. “And I used my spade as a paddle. It was lucky I had it with me.”

“Did you live on plankton?” queried another voice.

Paddington looked puzzled. “No,” he said. “Marmalade.”

Mr Brown pushed his way through the crowd. Paddington jumped up and looked rather guilty.

“Now then,” said Mr Brown, taking his paw. “That’s enough questions for today. This bear’s been at sea for a long time and he’s tired. In fact,” he looked meaningfully at Paddington, “he’s been at sea all the afternoon!”

“Is it still only Tuesday?” asked Paddington, innocently. “I thought it was much later than that!”

“Tuesday,” said Mr Brown firmly. “And we’ve been worried to death over you!”

Paddington picked up his bucket and spade and jar of marmalade. “Well,” he said. “I bet not many bears have gone to sea in a bucket, all the same.”

It was dark when they drove along Brightsea front on their way home. The promenade was festooned with coloured lights and even the fountains in the gardens kept changing colour. It all looked very pretty. But Paddington, who was lying in the back of the car wrapped in a blanket, was thinking of his sand-castle.