Полная версия

Paddington Complete Novels

“Henry, dear,” exclaimed Mrs Brown. “Do be careful. You’ll have coffee all over the sheets.”

“Coffee!” yelled Mr Brown. “Did you say this was coffee?”

“I didn’t, dear,” said Mrs Brown mildly. “Paddington did.” She took a sip from her own cup and then made a wry face. “It has got rather an unusual taste.”

“Unusual!” exclaimed Mr Brown. “It tastes like nothing on earth.” He glared at his cup and then poked at it gingerly with a spoon. “It’s got some funny green things floating in it too!” he exclaimed.

“Have a marmalade sandwich,” said Mrs Brown. “It’ll help take the taste away.”

Mr Brown gave his wife an expressive look. “Two days!” he said, sinking back into the bed. “Two whole days!”

Downstairs, Paddington was in a bit of a mess. So, for that matter was the kitchen, the hall, the dining-room and the stairs.

Things hadn’t really gone right since he’d lifted up a corner of the dining-room carpet in order to sweep some dust underneath and had discovered a number of very interesting old newspapers. Paddington sighed. Perhaps if he hadn’t spent so much time reading the newspapers he might not have hurried quite so much over the rest of the dusting. Then he might have been more careful when he shook Mrs Bird’s feather duster over the boiler.

And if he hadn’t set fire to Mrs Bird’s feather duster he might have been able to take more time over the coffee.

Paddington felt very guilty about the coffee and he rather wished he had tested it before taking it upstairs to Mr and Mrs Brown. He was very glad he’d decided to make cocoa for himself instead.

Quite early in the morning Paddington had run out of saucepans. It was the first big meal he had ever cooked and he wanted it to be something special. Having carefully consulted Mrs Bird’s cookery book he’d drawn out a special menu in red ink with a bit of everything on it.

But by the time he had put the stew to boil in one big saucepan, the potatoes in another saucepan, the peas in a third, the Brussels sprouts in yet another, and used at least four more for mixing operations, there was really only the electric kettle left in which to put the cabbage. Unfortunately, in his haste to make the coffee, Paddington had completely forgotten to take the cabbage out again.

Now he was having trouble with the dumplings!

Paddington was very keen on stew, especially when it was served with dumplings, but he was beginning to wish he had decided to cook something else for lunch.

Even now he wasn’t quite sure what had gone wrong. He’d looked up the chapter on dumplings in Mrs Bird’s cookery book and followed the instructions most carefully; putting two parts of flour to one of suet and then adding milk before stirring the whole lot together. But somehow, instead of the mixture turning into neat balls as it showed in the coloured picture, it had all gone runny. Then, when he’d added more flour and suet, it had gone lumpy instead and stuck to his fur, so that he’d had to add more milk and then more flour and suet, until he had a huge mountain of dumpling mixture in the middle of the kitchen table.

All in all, he decided, it just wasn’t his day. He wiped his paws carefully on Mrs Bird’s apron and, after looking around in vain for a large enough bowl, scraped the dumpling mixture into his hat.

It was a lot heavier than he had expected and he had a job lifting it up on to the stove. It was even more difficult putting the mixture into the stew as it kept sticking to his paws and as fast as he got it off one paw it stuck to the other. In the end he had to sit on the draining board and use the broom handle.

Paddington wasn’t very impressed with Mrs Bird’s cookery book. The instructions seemed all wrong. Not only had the dumplings been difficult to make, but the ones they showed in the picture were much too small. They weren’t a bit like the ones Mrs Bird usually served. Even Paddington rarely managed more than two of Mrs Bird’s dumplings.

Having scraped the last of the mixture off his paws Paddington pushed the saucepan lid hard down and scrambled clear. The steam from the saucepan had made his fur go soggy and he sat in the middle of the floor for several minutes getting his breath back and mopping his brow with an old dish-cloth.

It was while he was sitting there, scraping the remains of the dumplings out of his hat and licking the spoon, that he felt something move behind him. Not only that, but out of the corner of his eye he could see a shadow on the floor which definitely hadn’t been there a moment before.

Paddington sat very still, holding his breath and listening. It wasn’t so much a noise as a feeling, and it seemed to be creeping nearer and nearer, making a soft swishing noise as it came. Paddington felt his fur begin to stand on end as there came the sound of a slow plop… plop… plop across the kitchen floor. And then, just as he was summoning up enough courage to look over his shoulder, there was a loud crash from the direction of the stove. Without waiting to see what it was Paddington pulled his hat down over his head and ran, slamming the door behind him.

He arrived in the hall just as there was a loud knock on the front door. To his relief he heard a familiar voice call his name through the letterbox.

“I got your message, Mr Brown—about not being able to come for elevenses this morning,” began Mr Gruber, as Padddington opened the door, “and I just thought I would call round to see if there was anything I could do…” His voice trailed away as he stared at Paddington.

“Why, Mr Brown,” he exclaimed. “You’re all white! Is anything the matter?”

“Don’t worry, Mr Gruber,” cried Paddington, waving his paws in the air. “It’s only some of Mrs Bird’s flour. I’m afraid I can’t raise my hat because it’s stuck down with dumpling mixture – but I’m very glad you’ve come because there’s something nasty in the kitchen!”

“Something nasty in the kitchen?” echoed Mr Gruber. “What sort of thing?”

“I don’t know,” said Paddington, struggling with his hat. “But it’s got a shadow and it’s making a funny noise.”

Mr Gruber looked around nervously for something to defend himself with. “We’ll soon see about that,” he said, taking a warming pan off the wall.

Paddington led the way back to the kitchen and then stood to one side by the door. “After you, Mr Gruber,” he said politely.

“Er… thank you, Mr Brown,” said Mr Gruber doubtfully.

He grasped the warming pan firmly in both hands and then kicked open the door. “Come out!” he cried. “Whoever you are!”

“I don’t think it’s a who, Mr Gruber,” said Paddington, peering round the door. “It’s a what!”

“Good heavens!” exclaimed Mr Gruber, staring at the sight which met his eyes. “What has been going on?”

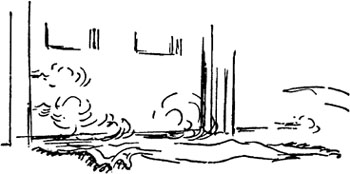

Over most of the kitchen there was a thin film of flour. There was flour on the table, in the sink, on the floor; in fact, over practically everything. But it wasn’t the general state of the room which made Mr Gruber cry out with surprise – it was the sight of something large and white hanging over the side of the stove.

He stared at it for a moment and then advanced cautiously across the kitchen and poked it with the handle of the warming pan. There was a loud squelching noise and Mr Gruber jumped back as part of it broke away and fell with a plop to the floor.

“Good heavens!” he exclaimed again. “I do believe it’s some kind of dumpling, Mr Brown. I’ve never seen quite such a big one before,” he went on as Paddington joined him. “It’s grown right out of the saucepan and pushed the lid on to the floor. No wonder it made you jump.”

Mr Gruber mopped his brow and opened the window. It was very warm in the kitchen. “How ever did it get to be that size?”

“I don’t really know, Mr Gruber,” said Paddington, looking puzzled. “It’s one of mine and it didn’t start off that way. I think something must have gone wrong in the saucepan.”

“I should think it has,” said Mr Gruber. “If I were you, Mr Brown, I think I’d turn the cooker off before it catches fire and does any more damage. There’s no knowing what might happen once it gets out of control.

“Perhaps, if you’ll allow me,” he continued tactfully, “I can give you a hand. It must be very difficult cooking for so many people.”

“It is when you only have paws, Mr Gruber,” said Paddington gratefully.

Mr Gruber sniffed. “I must say it all smells very nice. If we make some more dumplings quickly everything else should be just about ready.”

As he handed Paddington the flour and suet Mr Gruber explained how dumplings became very much larger when they were cooked and that it really needed only a small amount of mixture to make quite large ones.

“No wonder yours were so big, Mr Brown,” he said, as he lifted Paddington’s old dumpling into the washing-up bowl. “You must have used almost a bag of flour.”

“Two bags,” said Paddington, looking over his shoulder. “I don’t know what Mrs Bird will say when she hears about it.”

“Perhaps, if we buy her some more,” said Mr Gruber, as he staggered into the garden with the bowl, “she won’t mind quite so much.”

“That’s odd,” said Mr Brown, as he stared out of the bedroom window. “There’s a big white thing suddenly appeared in the garden. Just behind the nasturtiums.”

“Nonsense, Henry,” said Mrs Brown. “You must be seeing things.”

“I’m not,” said Mr Brown, rubbing his glasses and taking another look. “It’s all white and shapeless and it looks horrible. Mr Curry’s seen it too – he’s peering over the fence at it now. Do you know what it is, Paddington?”

“A big white thing, Mr Brown?” repeated Paddington vaguely, joining him at the window. “Perhaps it’s a snowball.”

“In summer?” said Mr Brown suspiciously.

“Henry,” said Mrs Brown. “Do come away from there and decide what you’re having for lunch. Paddington’s gone to a lot of trouble writing out a menu for us.”

Mr Brown took a large sheet of drawing paper from his wife and his face brightened as he studied it. It said:

MENUE

—

SOOP

—

FISH

OMMLETS

ROWST BEEF

Stew with Dumplings – Potatows

Brussle Sprowts Pees

Cabbidge – Greyvy

—

MARMALADE AND CUSTERD

—

COFFEY

“How nice!” exclaimed Mr Brown, when he had finished reading it. “And what a good idea putting pieces of vegetable on the side as illustrations. I’ve never seen that done before.”

“They’re not really meant to be there, Mr Brown,” said Paddington. “I’m afraid they came off my paws.”

“Oh,” said Mr Brown, brushing his moustache thoughtfully. “Hmm. Well, you know, I rather fancy some soup and fish myself.”

“I’m afraid they’re off,” said Paddington hastily, remembering a time when he’d once been taken out to lunch and they had arrived late.

“Off?” said Mr Brown. “But they can’t be. No one’s ordered anything yet.”

Mrs Brown drew him to one side. “I think we’re meant to have the stew and dumplings, Henry,” she whispered. “They’re underlined.”

“What’s that, Mary?” asked Mr Brown, who was a bit slow to grasp things at times. “Oh! Oh, I see… er… on second thoughts, Paddington, I think perhaps I’ll have the stew.”

“That’s good,” said Paddington, “because I’ve got it on a tray outside all ready”

“By Jove,” said Mr Brown, as Paddington staggered in breathing heavily and carrying first one plate and then another piled high with stew. “I must say I didn’t expect anything like this.”

“Did you cook it all by yourself, Paddington?” asked Mrs Brown.

“Well… almost all,” replied Paddington truthfully. “I had a bit of an accident with the dumplings and so Mr Gruber helped me make some more.”

“You’re sure you have enough for your own lunch?” said Mrs Brown anxiously.

“Oh, yes,” said Paddington, trying hard not to picture the kitchen, “there’s enough to last for days and days.”

“Well, I think you should be congratulated,” said Mr Brown. “I’m enjoying it no end. I bet there aren’t many bears who can say they’ve cooked a meal like this. It’s fit for a queen.”

Paddington’s eyes lit up with pleasure as he listened to Mr and Mrs Brown. It had been a lot of hard work but he was glad it had all been worth while—even if there was a lot of mess to clear up.

“You know, Henry,” said Mrs Brown, as Paddington hurried off downstairs to see Mr Gruber, “we ought to think ourselves very lucky having a bear like Paddington about the house in an emergency.”

Mr Brown lay back on his pillow and surveyed the mountain of food on his plate. “Doctor MacAndrew was right about one thing,” he said. “While Paddington’s looking after us, whatever else happens we certainly shan’t starve.”

The green front door of number thirty-two Windsor Gardens slowly opened and some whiskers and two black ears poked out through the gap. They turned first to the right, then to the left, and then suddenly disappeared from view again.

A few seconds later the quiet of the morning was broken by a strange trundling noise followed by a series of loud bumps as Paddington lowered Mr Brown’s wheelbarrow down the steps and on to the pavement. He peered up and down the street once more and then hurried back indoors.

Paddington made a number of journeys back and forth between the house and the wheelbarrow and each time he came through the front door he was carrying a large pile of things in his paws.

There were clothes, sheets, pillow-cases, towels, several tablecloths, not to mention a number of old jerseys belonging to Mr Curry, all of which he carefully placed in the barrow.

Paddington was pleased there was no one about. He felt sure that neither the Browns nor Mr Curry would approve if they knew he was taking their washing to the launderette in a wheelbarrow. But an emergency had arisen and Paddington wasn’t the sort of bear who allowed himself to be beaten by trifles.

Paddington had had a busy time what with one thing and another. Mrs Bird was due back shortly before lunch and there had been a lot of clearing up to do. He had spent most of the early part of the morning going round the house with what was left of her feather duster, getting rid of flour stains from the previous day’s cooking and generally making everything neat and tidy.

It was while he had been dusting the mantelpiece in the dining-room that he’d suddenly come across a small pile of money and one of Mrs Bird’s notes. Mrs Bird often left notes about the house reminding people to do certain things. This one was headed LAUNDRY and it was heavily underlined.

Not only did it say that the Browns’ laundry was due to be collected that very day, but it also had a postscript on the end saying that Mr Curry had arranged to send some things as well and would they please be collected.

Paddington hurried around as fast as he could but it still took him some while to gather together all the Browns’ washing, and having to fetch Mr Curry’s had delayed things even more. He’d been so busy making out a list of all the things that he’d quite failed to hear the knock at the front door and had arrived there just in time to see the laundry van disappearing down the road. Paddington had run after it shouting and waving his paws but either the driver hadn’t seen him, or he hadn’t wanted to, for the van had turned a corner before he was even halfway down Windsor Gardens.

It was while he was sitting on the pile of washing in the hall, trying to decide what to do next and how to explain it all to Mrs Bird, that the idea of the launderette had entered Paddington’s mind.

In the past Mr Gruber had often spoken to him on the subject of launderettes. Mr Gruber took his own washing along to one every Wednesday evening when they stayed open late.

“And very good it is, too, Mr Brown,” he was fond of saying. “You simply put the clothes into a big machine and then sit back while it does all the work for you. You meet some interesting people as well. I’ve had many a nice chat. And if you don’t want to chat you can always watch the washing going round and round inside the machine.”

Mr Gruber always made it sound most interesting and Paddington had often wanted to investigate the matter. The only difficulty as far as he could see was getting all the laundry there in the first place. The Browns always had a lot of washing, far too much to go into his shopping basket on wheels, and the launderette was some way away at the top of a hill.

In the end Mr Brown’s wheelbarrow had seemed the only answer to the problem. But now that he had finished loading it and was about to set off Paddington looked at it rather doubtfully. He could only just reach the handles with his paws and when he tried to lift the barrow it was much heavier than he had expected. Added to that, there was such a pile of washing on board he couldn’t see round the sides let alone over the top, which made pushing most difficult.

To be on the safe side he tied a handkerchief to the end of an old broomstick which he stuck in the front of the barrow to let people know he was coming. Paddington had often seen the same thing done on lorries when they had a heavy load, and he didn’t believe in taking any chances.

Quite a number of people turned to watch Paddington’s progress as he made his way slowly up the long hill. Several times he got the wheel caught in a drain and had to be helped out by a kindly passer-by, and at one point, when he had to cross a busy street, a policeman held up all the traffic for him.

Paddington thanked him very much and raised his hat to all the waiting cars and buses, which tooted their horns in reply.

It was a hot day and more than once he had to stop and mop his brow with a pillowcase, so that he wasn’t at all sorry when he rounded a corner and found himself outside the launderette.

He sat down on the edge of the pavement for a few minutes in order to get his breath back and when he got up again he was surprised to find a rusty old bicycle wheel lying on top of the washing.

“I expect someone thought you were a rag-and-bone bear,” said the stout, motherly lady in charge of the launderette, who came outside to see what was going on.

“A rag-and-bone bear?” exclaimed Paddington hotly. He looked most offended. “I’m not a rag-and-bone bear. I’m a laundry bear.”

The lady listened while Paddington explained what he had come for and at once called out for one of the other assistants to give him a hand up the steps with his barrow.

“I suppose you’re doing it for the whole street?” she asked, as she viewed the mountain of washing.

“Oh, no,” said Paddington, waving his paw vaguely in the direction of Windsor Gardens. “It’s for Mrs Bird.”

“Mrs Bird?” repeated the stout lady, looking at Mr Curry’s jerseys and some old gardening socks of Mr Brown’s which were lying on top of the pile. She opened her mouth as if she were about to say something but closed it again hurriedly when she saw Paddington staring at her.

“I’m afraid you’ll need four machines for all this lot,” she said briskly, as she went behind the counter. “It’s a good job it’s not one of our busy mornings. I’ll put you in the ones at the end – eleven, twelve, thirteen and fourteen – then you’ll be out of the way.” She looked at Paddington. “You do know how to work them?”

“I think so,” said Paddington, trying hard to remember all that Mr Gruber had told him.

“Well, if you get into any trouble the instructions are on the wall.” The lady handed Paddington eight little plastic tubs full of powder. “Here’s the soap powder,” she continued. “That’s two tubs for each machine. You tip one tubful in a hole in the top each time a red light comes on. That’ll be four pounds, please.”

Paddington counted out Mrs Bird’s money and after thanking the lady, began trundling his barrow along to the other end of the room.

As he steered his barrow in and out of people’s feet he looked around the launderette with interest. It was exactly as Mr Gruber had described it to him. The washing machines, all white and gleaming, were in a line round the walls and in the middle of the room were two long rows of chairs. The machines had glass portholes in their doors and Paddington peered through several of them as he went past and watched the washing going round and round in a flurry of soapy water.

By the time he reached the end of the room he felt quite excited and he was looking forward to having a go with the Browns’ washing.

Having climbed up on one of the chairs and examined the instructions on the wall, Paddington tipped his laundry out on to the floor and began sorting it into four piles putting all Mr Curry’s jerseys into one machine and all the Browns’ washing into the other three.

But although he had read the instructions most carefully Paddington soon began to wish Mr Gruber was there to advise him. First of all there was the matter of a knob on the front of each machine. It was marked ‘Hot Wash’ and ‘Warm Wash,’ and Paddington wasn’t at all sure about it. But being a bear who believed in getting his money’s worth he decided to turn them all to ‘Hot’.

And then there was the question of the soap. Having four machines to look after made things very difficult, especially as he had to climb up on a chair each time in order to put it in. No sooner had a red light gone out on one machine than another lit up and Paddington spent the first ten minutes rushing between the four machines pouring soap through the holes in the top as fast as he could. There was a nasty moment when he accidentally poured some soap into number ten by mistake and all the water bubbled over the side, but the lady whose machine it was was very nice about it and explained that she’d already put two lots in. Paddington was glad when at long last all the red lights went out and he was able to sit back on one of the seats and rest his paws.

He sat there for some while watching the washing being gently tossed round and round, but it was such a nice soothing motion and he felt so tired after his labours that in no time at all he dropped off to sleep. Suddenly he was brought back to life by the sound of a commotion and by someone poking him.

It was the stout lady in charge and she was staring at one of Paddington’s machines. “What have you got in number fourteen?” she demanded.

“Number fourteen?” Paddington thought for a moment and then consulted his laundry list. “I think I put some jerseys in there,” he said.

The stout lady raised her hands in horror. “Oh, Else,” she cried, calling to one of her assistants. “There’s a young bear here put ’is jerseys in number fourteen by mistake!”