Полная версия

Panda Panic - Running Wild

For Ben, Jack, Charlotte, Jolyon, Isabel and Robbie who at some stage in their lives have all run around with a Little Bear behind.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Copyright

About The Publisher

Ping leapt out behind them.

“Where are you going with my Emperor?” he growled.

“And who are you?” snarled Stinkie McScar, the bandit leader, as he turned round slowly and spat out a tooth.

“The name’s Ping!” said Ping. Then with a bloodcurdling wail of “Banshai!” he sprang forward, floored Stinkie with a ninja kick, snatched the Emperor off the horse and set off at a run down the Great Wall of China with the bandits giving chase.

“Where are you taking me?” the Emperor screamed as he bounced up and down on the panda cub’s back.

“To safety,” came Ping’s steely reply. “Now shut your royal cakehole and hold your breath.” And with that, Ping leapt off the top of the Great Wall and plunged three hundred feet into the river below. The water was cold and the current strong, but Ping was a powerful swimmer and in less than six strokes he had the Emperor safe on the bank.

“My moustache is wet,” said the Emperor.

“Just be thankful you’ve still got a head to grow one on,” said Ping. “We’re not out of the woods yet, Your Emperorship.”

Screaming blue murder, the bandits burst out of the trees and ran towards them. Ping wrapped his arms round the Emperor’s waist and back-flipped on to the top of a mound of dry earth.

“We’re safe up here,” he said. “Now blow them a raspberry.”

“But I’m an Emperor,” said the Emperor. “And Emperors must remain dignified at all times.”

“Then it’s lucky I’m here!” roared Ping, spinning round, waggling his bottom andblowing a raspberry at Stinkie McScar through his legs. Inflamed by the panda cub’s insult, the bandits charged, but just as they were within striking distance, Ping grabbed the Emperor for a second time and somersaulted off the mound.

“Hey, ugly muglies,” Ping shouted up at the bandits, who were now standing in a huddle on the top. “Check out what’s under your feet.” Even as he spoke the mound collapsed under their weight and the bandits were plunged into a nest of deadly termites, that crawled inside their heads and gobbled them up from the inside out.

That was when Ping woke up.

“Oh, fiddlesticks,” he groaned, taking in his surroundings. “Another day, another daydream.”

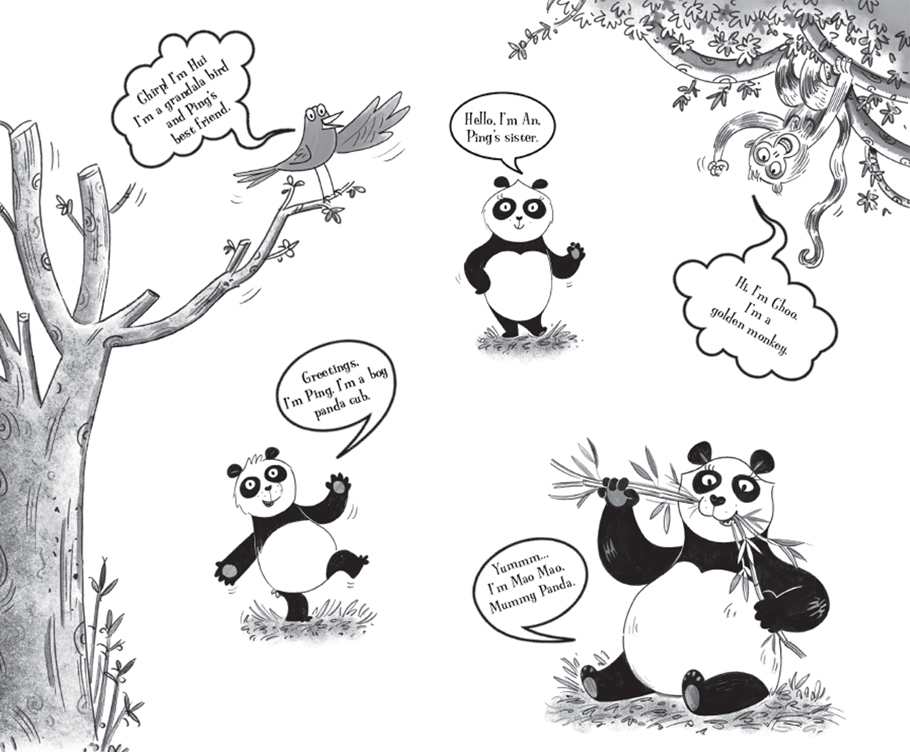

It was first thing in the morning, and Ping was lying on a bed of rhododendron leaves in a clearing in the Wolagong Nature Reserve. Next to him lay his mother, Mao Mao, and twin sister, An, both smiling serenely as they chomped on opposite ends of the same stick of bamboo.

“Bamboo in bed,” smiled Ping’s mother. “Heavenly. Do you want some, Ping?”

Ping shook his head.

“What were you dreaming about?” demanded his sister. “You were sucking in your tummy and jumping up and down and twirling your arms around like a windmill.”

“None of your business,” Ping said grumpily.

“You were dreaming about being the Emperor’s bodyguard again, weren’t you?” she snorted.

“Might have been,” said Ping evasively. “I don’t see why you think it’s so funny.”

“Because you’re a lazy, fat panda, not a fit, muscled action hero! The only way you could guard the Emperor is if you wedged yourself into the doorway of his bedroom so that nobody could get in.”

“If you must know, I was dreaming that I was actually doing something for once.”

“Why?”

“Because I’m bored!” he shouted. It wasn’t that Ping didn’t like eating bamboo, or digging a hole in the forest forty-seven times a day so that he could have yet another poo, or even that he objected to smiling continuously for the visitors’ clickety-clack cameras, but when that was ALL he ever did, his life quickly became rather boring.

“I’ve had an idea,” he said, jumping to his feet enthusiastically.

“Oh, here we go,” said An with a sigh.

“What do you mean, ‘Oh, here we go’? I haven’t gone anywhere yet,” protested Ping. “If you don’t mind me saying so, An, that’s a rotten thing for a brother to hear from his sister just after he’s woken up.”

“It’s because you say the same thing every morning,” she explained. Then, adopting a look of mock excitement, she mimicked Ping’s voice. “‘Oooh! Oooh! Oooh! Oooh! An! Listen. I’ve had a completely brilliant idea. I was wondering how you felt about climbing a tree today?’” She stopped imitating Ping and spoke in her own voice again. “The same as I always feel about climbing a tree, Ping. The same as I feel about swimming across a river, or rolling down a hill, or running in a race, or throwing a stick. I would rather I was sitting here eating bamboo with Mummy.”

“You’d never make an adventurer,” Ping observed.

“I don’t want to be an adventurer,” she said. “I’m happy at home.”

“As should you be, Ping,” his mother interjected. “A stranger who walks in a strange land knows not where to hide from the toothsome smile of a predator.” Ping had never been able to understand his mother’s sayings. It seemed to him that she just picked out unrelated words and arranged them at random into baffling sentences.

“You don’t understand what Mummy’s just said, do you?” jeered An. “You’re trying to look like you do, but you haven’t got a clue!”

“Of course I understand,” said Ping. “It’s got something to do with going on holiday and forgetting your toothbrush… I think.”

“Wrong,” said his sister, smugly. “It means that I am the clever one and you are not, because I do understand it. It means that panda cubs are safer at home, because the rainy season’s just finished and the snow leopards are coming down from the mountains looking for food!”

“I’m not scared of snow leopards!” Ping scoffed. “Is that why you won’t go exploring with me?”

“Yes,” said An. “When I’m at home I know where to hide. And that is why, in case you were wondering, I’m so much better at hide-and-seek than you.”

“No, you’re not!” said Ping. Then, realising he could turn this to his advantage, he added, “Prove it!”

An yawned.

“You don’t catch me out that easily,” she said. “Besides, I’m too young and pretty to be a snow leopard snack just yet, but you go ahead if you want to.”

Their mother chuckled.

“Nobody’s going to be eaten by a snow leopard,” she said.

“At least it would be a bit of excitement,” Ping replied, without thinking.

“That is a ridiculous thing to say,” his mother sighed. “The wise panda searches not for what he does not have, but is content with what is his.”

Ping was baffled again and scratched his head.

“Master the art of boredom,” she explained further, “and you will conquer the world.”

“How can you master boredom?” he asked. “Boredom’s just boring.”

“If you’re bored,” she said quietly, “it’s up to you to go off and find something to do.”

“Like what?”

“Like fishing,” she suggested.

“Fishing’s boring,” said Ping.

“Fishing’s safe,” his mother said.

“So long as you don’t fall into the water,” sniggered An. “Which Ping probably would, because he’s as clumsy as a fat fairy in concrete boots.”

“And it is the end of the rainy season, so the river’s running rather fast at the moment,” said his mother anxiously. “Actually, I’ve changed my mind, Ping. Maybe fishing’s not a good idea. Why don’t you ask your best friend, Hui, to play with you?”

Hui was a bright-blue grandala bird who entertained Ping for hours with his exciting stories about flying around the world.

“Because he’s busy catching insects for his winter nest,” said Ping. “He said I could help him, but I hate bugs. They nest in my fur and tickle me.” Ping scratched his nose and tipped back his head to look at the sky. “You know, sometimes I wish I wasn’t a panda. Sometimes I wish I was a bird, like Hui, because birds can go wherever they like.”

“You can’t be a bird,” said An, “because birds have got a head for heights. You’ve got a head for basketball.”

“I’m not staying here to be insulted,” Ping said, standing up in a huff. “And anyway, if my head is the shape of a basketball, yours must be too. So there!”

“Will you two please stop arguing,” said their mother. “You can go off and have a silly adventure, Ping, but don’t do anything dangerous, make sure you’re back for supper, and watch out for snow leopards!”

“Maybe I will and maybe I won’t,” he grumbled, kicking his way through a bamboo hedge and stomping out of the clearing.

The moment he was out of sight Ping felt guilty. He shouldn’t be speaking to his mother like that. After all, she was only trying to keep him safe. And she had actually met a snow leopard once, so she knew how dangerous they could be. He’d better say sorry… Yes, that would be the kind thing to do… Maybe not now, though. After he’d had his adventure. He’d do it tonight, when he came home for supper.

“Ping.”

Ping spun round, surprised to find his sister standing close behind him.

“Promise me,” she said seriously, “that whatever it is you end up doing today it won’t be anything stupid!”

Ping laughed at the very idea.

“As if I would,” he said. “As if I would!”

Then he disappeared into the bushes to find himself a surfboard.

As luck would have it, five minutes later, as he wandered past the fat ranger’s office, he stumbled upon the perfect piece of wood lying across his path. Someone had even smartened it up for him by painting it bright green. He went to knock on the back door of the office to ask if he might take it, but to his surprise there was no door, just a hole in the wall where a door had once been. He waited outside the office for a couple of minutes, but nobody came, so he helped himself and, clamping his new surfboard underneath his arm, he set off for the River Trickle.

When he arrived he was surprised at how different the river looked. He had never seen it after the rainy season. It was at least six times wider than normal and as deep as the tallest tree in the forest. It rushed past faster than a galloping horse and roared like a cloud full of thunder. Luckily there was a shallow pool to one side where Ping could do his warm-up. It was the vet who had taught him how important it was to stretch before physical activity and he started his warm-up by lunging forward on his left leg while touching the ground with the knee of the right. After ten seconds of grunting he swapped legs, lunging forward on his right leg while touching the ground with the knee of the left. It was frightfully complicated, and Ping started to get in a bit of a muddle. When it came to stretching his arms, he couldn’t remember if they should be pointing up or down, or whether he should be bending forward or standing up, or whether his feet should be pointing in or out, or whether he should shut his eyes or keep them open.

After five minutes of warming up he was in trouble. Bending at the waist, he had threaded both of his arms between his legs from behind, grabbed on to his ankles and then tried to stand up. But when he came to pull his arms back again they were knotted round his knees. He slowly toppled forward until his forehead was resting on the ground. With his black and white bottom sticking up in the air and his head curled under his tummy he looked like a rolled-up woodlouse. Now what was he going to do? Unfortunately this decision was taken out of his hands, because just then, with whoops and mocking cheers, the golden monkeys arrived to poke fun at poor Ping. They sat in the branches above him and poured scorn down at him.

“Oh, look,” screamed Choo, their oh-so-witty leader. “A weird new animal’s come to live in the forest… It’s a giant black and white snail.” The other monkeys laughed, while a cocky young monkey called Foo approached Ping and sniffed him.

“It smells like a panda,” he said. “But it can’t be a panda, because pandas only ever do three things – eat bamboo, poo forty-seven times a day and pose for tourists’ cameras – and this one,” he said, running his finger down Ping’s curved back, “is trying to be a ski slope!”

“You know very well I’m a panda,” said Ping.

The monkeys leapt backwards on their branches pretending to be shocked.

“A snail that can TALK!” they yelled, bursting into another chatter of laughter.

“Can you un-knot me, please?” Ping asked.

“My pleasure,” said Choo, dropping to the ground and delivering a light kick to the panda cub’s bottom. Ping rolled forward into the water and uncurled with a splash.

“Thank you,” he said, getting to his feet with as much dignity as he could muster. “Now if you’ll excuse me, I’m busy.”

“You! Busy!” sniggered Choo. “The last time I saw a busy panda was never!”

“He’s busy paddling in the water,” snorted Foo.

“Paddling’s for babies,” Choo roared. “Are you sure you shouldn’t be wearing armbands?”

“I am not paddling,” said Ping. “I am surfing.”

Never before had the monkeys laughed so hard. Their jags of laughter skimmed across the surface of the water like sharp stones.

“We’ve seen your surfing before, Ping, and there is only one way to describe it,” sniggered Choo. “It STINKS! Talking of which, we’ve got a new name for you – Ping PONG!”

This time the monkeys laughed so hard that they couldn’t catch their breath.

Ping had had enough of their jibes. He’d jolly well show these stupid monkeys. He waded out into the middle of the river, which was running a whole lot faster than he had thought, and hopped up on to his board. At first he found it almost impossible to get his balance. His arms whirled, his knees buckled and he wobbled around like a jack-in-the-box on a spring, but then he bent his knees, spread out his arms and sat back on his haunches… and suddenly he was in control. The current grabbed hold of his board and, with a kick like an outboard motor, whooshed him off downriver.

“Wooooohooooo!” Ping yelled. “I’m doing it! I’m the King of the Surf!” He couldn’t see them, but he could hear quite distinctly that the monkeys had stopped laughing. The river bent sharply to the right, allowing Ping to glance back over his shoulder, where, to his delight, he saw that the monkeys were so shocked to see him surfing that they had fallen out of their trees and were thrashing around in the water trying to get out.

“You should have had some armbands!” hollered Ping. “So long, suckers!” And with a final cry of, “Now you see me, now you don’t!” he disappeared round the bend.

The River Trickle twisted and turned through the Wolagong Nature Reserve like a miniature train in a zoo. It carried Ping past all of the other pandas, who seemed strangely unperturbed by the extraordinary sight, as if a panda on a surfboard was something they saw every day. They turned their gentle eyes to watch him pass, but not once did they stop chewing.

Ping floated past the fat ranger, who was madly searching for something in the garden outside his office. Upon hearing Ping’s cry of “Cowabunga!” the fat ranger lifted his head out of a bush and pointed at Ping’s surfboard.

“There it is!” he screamed. “There’s my back door!”

“Back door!” gulped Ping, looking down at the board beneath his feet. Now that he studied it more closely he noticed that it had a handle and a cat flap. The fat ranger loved his cats.

“And the paint’s wet!” shouted the fat ranger.

Nothing I can do about that, thought Ping. That’s the problem with surfing – everything gets wet… my face, my legs, my feet, the board, the paint. He noticed that the fat ranger was waving a paintbrush. “Oh, I see what you mean!” gasped Ping, lifting up his feet to discover that underneath they were bright green. “You mean the paint’s still wet. Sorry!” he cried as he sailed past. “I’ll have the door back in two shakes of a cat’s tail.”

But the cats would have to wait a little longer than that, because Ping’s bright-green door-board showed no sign of stopping.

“Look at meeeeeeee!” Ping screamed, punching the air for all he was worth. “I’m living the dream!”

An hour later, swept along by the roaring river, Ping was miles away from home, in a part of the reserve he had never been to before. At last, he was in the middle of his own adventure. It was all he’d ever wanted. And it felt good.

We’re brave, we’re brave, we’re on a wave,

We’re wet the whole way through.

We’re great, we’re great, when we do skate

On rivers deep and blue.

Our floor, our floor, is fatty’s door,

No time to eat bamboo.

The rocks, the rocks scare off our socks,

I really need a poo!

Ping sang the last line on his own. The frogs stopped the moment they heard the words and looked at Ping with their wide mouths wide open.

“That is the rudest thing I have ever heard,” croaked a matronly frog called Lu Chu. “What possessed you to sing it?”

“I need a poo,” said Ping matter-of-factly. “It’s no big deal. We pandas poo forty-seven times a day. We talk about it all the time.”

“Well, we DON’T!” harrumphed Lu Chu. “Our best friends are the high-born emperor ducks, and if they were ever to hear us croaking such crudities they would terminate our friendship immediately!” And with that she belly-flopped into the water and disappeared in a ripple of red rage.

When he wasn’t singing with frogs, Ping was making all kinds of other friends. He gave extreme-waterskiing lessons to baby crocodiles by letting them hang on to his tail with their teeth. “There’s only one rule,” he informed them at the start of each lesson. “No biting!”

He rescued a squirrel from a floating log, skimmed over the backs of water buffalo as they waded across the river in front of him and, with a cry of, “Bullseye!” he jumped through the body loops of a surprised python while it dangled from a tree.

But by far his favourite friends were the fish, which swam alongside his board and jumped out of the water like hungry dogs leaping for a juicy steak on a hook in a butcher’s shop.

“What sort of fish are you?” Ping asked one of them, a cod-faced fellow with whiskers.

“A catfish,” the fish replied.

“Does that mean you’re half cat and half fish?” enquired Ping. “Does the cat half of you look at the fish half of you and think, ‘Gosh! I look delicious. I could happily eat myself with a saucer of milk’?”

“Funnily enough, no,” said the fish gloomily. “I’m a fish through and through. Are you a pandafish?”