Полная версия

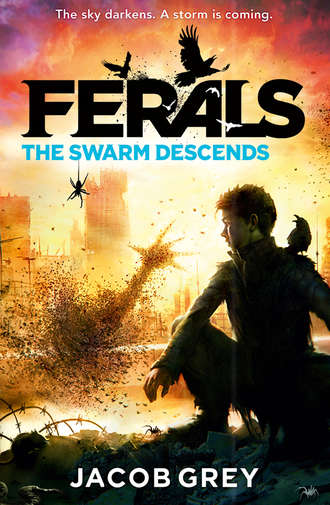

The Swarm Descends

Copyright

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Children’s Books 2015

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd,

HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

The HarperCollins Children’s Books website address is www.harpercollins.co.uk

Ferals: The Swarm Descends

Text © Working Partners Ltd 2015

Covert art © Jeff Nentrup, 2015

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007578542

Ebook Edition © 2015 ISBN: 9780007578559

Version: 2015-07-30

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Acknowledgements

Also Available

About the Publisher

He checked the watch Crumb had given him – 2am.

This is a bad idea, said Glum. He was perched on a branch ten feet above, beak resting in the thick plumage of his chest feathers. I’m older than you. Why does no one ever listen to the voice of experience?

“I did listen,” said Caw. “I just chose to ignore you.”

He tried to sound confident, but his mouth was dry as he crouched, shivering, in the bushes. The house in front of him was abandoned, its walls flaking and covered in graffiti. He counted two intact windows, while the rest were either cracked or boarded up. The front lawn was so overgrown there wasn’t even a path to the door. One of the trees that grew beside the house had blown over in a storm and its branches, which had crushed a section of the roof, now appeared to be growing into the building.

Home sweet home, muttered Screech, hopping nervously along Caw’s shoulder. The young crow’s claws pricked Caw’s skin, even through the leather of his coat.

Home? thought Caw. It didn’t feel like it. Not at all.

He searched his memories, but couldn’t find this place among them. He’d been five years old when the crows had carried him away, and nothing about the building in front of him was familiar. Except the unsettling feeling of dread he felt as he looked at it; the same feeling he had in his dreams.

Not too late to go back to the church, Caw, said Glum. We could have those leftover sweet potato pancakes from dinner. Besides, how do we even know this is the right place?

“I just know,” said Caw, feeling cold certainty in his gut.

A snap of fluttering wings sounded at his back and a third crow alighted on the ground. Wiry and sleek, she stabbed a slender beak into the earth and prised up a wriggling worm. The slimy creature squirmed and coiled as the crow tossed back her head and gobbled it down.

Hey, Shimmer! said Screech, puffing out his chest.

Coast’s clear, the female crow said, loose crumbs of earth dropping from her beak. What are you all waiting for?

For this young man to see sense, said Glum. To let history lie.

Don’t be such a killjoy, said Shimmer, stretching her wings. They were sheened with blues and reds like spilt oil on wet tarmac. It took me four weeks to find this place. If Caw’s not going in, I am.

“Can you all stop talking about me as if I’m not here?” said Caw. For once, the crows ceased their bickering. It was a rare occurrence since Shimmer had joined the group. Crows were stubborn. They liked to argue, and they liked having the last word even more. All except Milky, the white crow that Caw had grown up with. In all the years in the nest, he’d spoken less than twenty words. Caw wished the old crow was still with them.

He stood up, stretching his lower back and casting a glance back along the street. None of the buildings in this part of town was inhabited any more. The families had all moved out when the jobs dried up after the Dark Summer – the secret war between ferals that had broken out eight years ago. A broken and rusted scooter lay in a gutter full of leaves, and below, in a tree in a front garden, hung a lopsided swing, its cords frayed.

Caw wondered for a moment what it had been like growing up here. Had he played with other children from these now-abandoned houses? It was hard to imagine sounds of laughter in a place so dismal and heavy with silence. He began to make his way up the driveway towards the house, heart thumping. The front door was boarded up, but he could climb in through a window easily enough.

You can still turn back, said Glum, remaining stubbornly perched on his branch.

It was easy for Glum to say: this house meant nothing to him. But for Caw, it was everything. For so many years his past was a blank – an open sea with no charts to guide him. But this place was a landmark, and he couldn’t ignore it any longer. Who knew what he might find inside?

He reached into his jacket pocket and pulled out the crumpled photo – a picture of his parents, from happier times. Crumb had given it to him. The pigeon feral hadn’t wanted Caw to come tonight either – grumbling that it was “a waste of time”. Caw let his thumb brush across his parents’ faces. They looked almost exactly the same as they had when he found them in the Land of the Dead. He’d only managed to share a few precious moments with them, and it had left his heart aching for more. Where better to find out about them than this place?

He owed it to them not to turn back.

As Caw laid a hand on one of the boards over the door, he found that it was loose. He gripped the edge firmly and easily yanked it free, rusting nails and all. The others posed no more bother, and soon he’d cleared the way.

Caw sensed the crows behind him and turned. Sure enough, all three were perched on the ground.

“Let me go in alone,” he said.

Shimmer nodded and Screech hopped back a few steps. Glum looked away with a dramatic toss of his head.

There was a light switch inside, but Caw wasn’t surprised that nothing happened when he pressed it. The air was cool and musty. In the gloom, he made out overturned furniture and pictures hanging lopsidedly from the walls. A grand staircase rose from the entrance hall up to a landing, then doubled back on itself to the first floor level. Caw thought he saw something move up there – a rat, or a bird, perhaps, but when he looked again there was nothing.

Caw felt a dim sense of belonging. Small things looked familiar – a lampshade, a doorknob, a tattered curtain. Or maybe it was just his mind playing tricks, wanting to see something significant among the debris of abandoned lives.

Through an archway, Caw could see a sagging couch and wires protruding from a wall socket, and as he walked towards it the view opened on to a dining table.

A rush of fear turned his feet to lead. He knew this room from his nightmares. It was here that it had happened – beside that very table his parents had been murdered by the spiders of the Spinning Man. The table was covered in dust now, but Caw couldn’t bring himself to step any closer.

Instead, he turned back to the stairs. They creaked as he climbed. With each step, a haunting nostalgia swelled in his stomach. When he reached the first floor, his feet carried him automatically towards a door with a small placard in the shape of a train. Painted on it were words he recognised from Crumb’s lessons – “Jack’s Room”.

Jack Carmichael.

That had been his name, once.

Caw took a deep breath and pushed the door open.

On the opposite wall, his eyes fell on the window and his knees turned to water. The memories, so dream-like, crystallised into a feeling of pure fear. Caw gripped the doorframe to steady himself.

He remembered the firm hands of his parents as they dragged him from his bed and hauled him towards the window. Their fingers had been so tight it had hurt and their ears had seemed deaf to his screams of panic. Then his father had opened the window and his mother had thrust him out. Caw had watched the ground spinning towards him, felt the terror rising as he fell …

He took a deep breath as the power of the memory faded.

For years, that had been his only remembrance of them, festering in his mind. Their heartless abandonment. Now he knew it wasn’t the full story. It was just one line in a tale that had begun centuries ago – a tale of ferals at war with one another. His parents hadn’t been trying to kill him – they’d been protecting him, by getting him as far away from the Spinning Man as possible.

Caw opened his eyes, looking away from the window. He was trembling.

The rest of the room was practically empty. A couple of shelves held scraps of paper; and bundles of old clothing had been pushed into one corner. Caw hadn’t been expecting the room to be preserved like a museum, but still he felt a rush of rage. Someone had taken all of his things.

The anger seeped away as quickly as it had come, leaving only a numb sorrow. Of course the house had been ransacked and looted. Plenty of petty criminals had taken advantage of the chaos caused by the Dark Summer. Caw guessed a nice house like this would have made for easy pickings.

He let his feet carry him across the mould-covered carpet towards the window. The glass was cracked, and he rubbed a sheen of condensation away with the cuff of his leather jacket. Outside the night was still, the stars bright in a cloudless sky, the moon glowing softly.

Caw sighed. Crumb was right – there was no point in coming here. The past was dead.

Then, in the trees below, he saw something. A pale face materialising from the darkness beside a tree trunk.

Caw’s heart jolted. The face didn’t move at all, just stared up at him. It was an old man, with skin so white he might have been wearing make-up like a clown. Who was he? And what was he doing here, in Caw’s garden?

Caw gripped the window frame. He tried to yank it up to call out to the man, but it didn’t budge. He heaved again and it gave a grating screech. He was about to open his mouth when he heard a panicked intake of breath at his back.

“Who are you?” said a voice.

Caw spun round and saw the pile of clothes in the corner stirring. There was a girl lying there, wrapped in a sleeping bag. She was skinny, with dark tangled hair framing her grubby face. She looked a year or two older than him.

Caw stepped back until he collided with the window. His leg muscles wanted to run, but fear paralysed him. He found his voice.

“I …” he started. But what was he supposed to say? Where to start? Her eyes were defiant, but scared too, he noticed, his fear dipping slightly. He raised his hands to show he wasn’t a threat. “This is my house,” he said. “Who are you?”

The girl stood up, shaking the sleeping bag off. She picked up a baseball bat from beside her, knuckles white as they clenched it.

“Are you on your own?” said the girl.

Caw remembered the man outside and took a quick glance back. But the face by the tree had gone. The crows were nowhere to be seen either.

“Er … yes,” he said.

“So, if this is your house, why don’t you live here?” the girl said, jabbing the bat at him. She looked like she wouldn’t have a problem using it.

Caw kept his distance. “I haven’t lived here for a long time,” he said. He searched for a better explanation but couldn’t think what to say.

The girl hefted the bat again. She looked ready to pounce if he said the wrong thing.

“My parents … they threw me out,” he added. It was sort of true.

The girl seemed to relax at that. She lowered the bat a little. “Join the club,” she said.

“What club?” said Caw.

The girl frowned. “It’s an expression,” she said. “It means we’re in the same boat.”

Caw was getting confused. “This is a house, not a boat,” he said.

He wasn’t sure why, but the girl laughed at that. “What planet are you from?” she said, shaking her head.

“This one,” said Caw. She was making fun of him, he realised. But at least that was better than trying to bludgeon him with a bat. “Are you on your own?” he asked.

The girl nodded. “I suppose technically I ran away. I’ve been here a few weeks. My name’s Selina, by the way.”

“Caw,” said Caw.

“That short for something?”

“Not really,” he replied.

“I knew there were some empty houses round here,” said Selina. She waved the bat, pointing around the room. “This seemed the best of a bad lot.”

“Thanks,” said Caw. “This used to be my bedroom.”

The girl grinned. “It’s really nice. The rat droppings make it kind of homely.”

Caw couldn’t help laughing. It had taken him a while, but gradually, with Pip and Crumb’s help, he was getting the hang of talking to people. “It’s the charred curtains that make it for me.”

Selina leant the baseball bat against the wall. “Look, I can go if you want.”

Caw went quiet. He felt sort of strange in the pit of his stomach. No one ever asked what he wanted, so he had no idea. He looked at her ragged clothes and thin face. If he kicked her out, where would she go? He supposed there were other houses she could squat in. But he’d only just met her, and she seemed OK, apart from the baseball bat.

The girl began to gather the sleeping bag up from the floor.

“There’s no need to leave,” he said quickly. “I’m not staying. I’m finished here.”

She paused. “Oh – you live somewhere else now?” she said.

Caw caught a flash of desperation in her eyes. He thought about the Church of St Francis, where he lived with Crumb and Pip. He broke eye contact.

“Sort of,” he said.

Selina gave a wry smile. “It’s OK – I get it. I can look after myself.”

Caw searched her face and wondered if she was just pretending to be tough. He had a mattress at the church, warmth and food. A million times better than here. Could he take her there? There was plenty of room. His heart urged him to say something, but his head argued the other way. He knew Crumb wouldn’t like it if he showed up with a stranger. Plus, how could they keep their feral powers a secret from her?

No, it was too risky.

“It’s not that,” he said. “It’s not my place, that’s all.”

She nodded. “Don’t worry about it.”

He felt bad. It must get really cold here at night. And how did she eat without any crows to help her?

“Listen,” he said, “you look hungry. I could come back, bring you some food if you like.”

The girl blushed, but lifted her chin. “I don’t need your help,” she said.

“No, of course not,” said Caw. “I was just … I know places to get food, that’s all. In the city.”

“So do I,” she said defensively. “I’m not going hungry, all right?”

An uncomfortable silence fell over the room. He hadn’t meant to offend her.

“Tell you what,” she said at last. “How about we share our knowledge? I’ll show you where I go, and you can do the same. Two runaways helping each other out?”

Caw blinked. He hadn’t been expecting that sort of offer. “What – like, together?”

“Why not?” said Selina. “How about tomorrow night? Ten o’clock.”

Caw found himself nodding without even thinking about it.

Screech’s soft warble sounded from outside. They must be worried about me. Caw didn’t want them coming in and scaring Selina.

“I’ve got to go,” he said.

She was watching him closely, her brow wrinkled. “OK,” she said. “Bye, Caw – see you tomorrow. I’ll guard your parents’ valuables till then.”

“Valuables?” said Caw. Had she found something in the house?

She smiled again. “Joking,” she said.

“Oh, yes,” he said, going red. “I get it. Bye then.”

He left the room, skin still burning furiously. But as he began descending the stairs, his chest felt light. It had been so long since he’d spoken to a normal person, and apart from a few slips, it hadn’t gone too badly. He wondered if he should tell Crumb about the girl. The pigeon feral didn’t have a lot of time for non-ferals.

He paused in the living room. All sorts of questions occurred to him now. Where had she run from, and why? How long had she been here and how had she survived? Well, there’d be plenty of time to ask her later.

Find anything? said Shimmer, hopping aside as he closed the front door behind him.

“Not really,” Caw lied. “Come on, let’s go home.”

Nothing at all? said Shimmer, cocking her head.

“It’s a ruin,” said Caw. “I should have listened to Glum.”

Told you so, said Glum.

Caw knew he should tell them about Selina, but they’d only object, just as they had with Lydia. Besides, all his life the crows had kept secrets from him. It was oddly satisfying to have one of his own – even if it was only something small.

They had just reached the end of the front lawn, when a figure stepped out ahead of them.

Caw was gripped with an icy panic. He gasped, and the crows took to the air with wild cries. He backed up, tripped and fell on to his backside. Every fibre of his muscles wanted to run, but he felt completely unable to move.

The man thrust his head forward. “Jack Carmichael?” he said. His voice was soft but urgent. Caw noticed with a wave of revulsion that the man’s teeth were sharp shards of enamel jutting from his gums.

You know him? said Screech.

Caw managed to shake his head. It was the man with the white face that he’d seen from his bedroom window. Up close, Caw saw that his features looked pale too – bloodless lips, a squashed little nose and wide, unblinking eyes staring out from behind small tinted spectacles. His face was skeletally thin, with dark hollows beneath his cheekbones, and he had no hair and no eyebrows at all. He wore a long black coat tightly buttoned up.

Shimmer leapt into a branch above the man and let out a harsh shriek.

“I mean no harm,” said the man, casting rapid glances to either side. “That’s if you are Jack Carmichael? The crow talker.”

“Who are you?” said Caw, picking himself up. “Why are you spying on me?”

The pale figure reached into his coat and Caw bristled. He saw Glum spread his wings, ready to swoop down. But what the man drew out wasn’t a weapon. It was a stone, about half the size of Caw’s fist and polished to a jet-black shine.

“This is from Elizabeth,” said the stranger, holding it in front of him. “Elizabeth Carmichael.”

Caw felt the words tugging at his heart. “My mother? You knew her?”

“Perhaps,” said the man. He hesitated. “I suppose I must have. Once.” His mouth twitched into the ghost of a smile that vanished just as quickly. “Closer to her than ever now, of course.”

Er … what’s that supposed to mean? said Shimmer.

Caw stared at the stone sitting in the man’s hand. The harder he looked, the harder it was to focus on its edges. It wasn’t completely black at all – in its depths, swirls of colour seemed to shift and blur. Caw drew back and the man stepped after him, thrusting the stone towards him.

“It belongs to you, young man. To the crow feral. Take it. Take it.”

It might be a trap, said Screech.

Caw could hear the desperation in the stranger’s words, but somehow he felt sure it was the truth. The stone was his. He knew it, deep in his soul. He extended a hand and the man dropped the stone into his palm. It was lighter than Caw had expected and oddly warm.

“What is it?” asked Caw.

Instead of replying, the man jerked his pale face upwards and shrank back into the darkness. “I must go,” he said. “I want nothing to do with it, crow talker. It is yours to bear alone.”

Caw turned and saw a pigeon flap out of a window at the rear of his parents’ house. One of Crumb’s birds. It flew away like a grey shadow.

He closed his fist around the stone. He was dimly aware of the crows making noises, but he was too focused on the strange feeling of the stone throbbing in his palm. Maybe it was just the pulse of his blood?

When Caw looked up again, the stranger was gone. Screech landed on his shoulder and gave his ear a light nip with his beak.

“Ow!” said Caw. “Why’d you do that?” He slipped the stone into his pocket.

Because you weren’t listening, said Screech. Are you OK?

Caw nodded slowly. “Let’s get back to the church. And … we’ll keep this to ourselves, all right?”

Screech chuckled. Who are we going to tell? It’s not as if anyone else understands crow, is it?

“Good point,” said Caw.

Sausages …

He rolled over, scattering the pile of books stacked beside his mattress. At once, the memory of the night rushed back. The stone, the stranger.

Crumb was a few metres away, leaning over his brazier, with his back to Caw, turning spitting sausages in a skillet. Pip sat beside him, letting a mouse run up and down, under and over his sleeve. He was wrapped in an army jacket at least three sizes too big for him and his scruffy fair hair needed a good brush. He looked longingly at the pan.

“They must be ready by now!” said the mouse feral.

“Patience,” said Crumb.

On one of the roof beams, a pigeon cooed.

“Awake, is he?” said Crumb. “I’m surprised after all that sneaking around last night.”