Полная версия

The Doldrums and the Helmsley Curse

Archer hadn’t seen Miss Whitewood since before the tiger incident, but he was pleased to discover she still smelled like books. “The Raven Wood head of school wanted to speak with you,” he said. “Mr. Churnick. Did you ever talk to him?”

“I did,” Miss Whitewood replied, handing him a small card. “I gave one to Oliver and Adélaïde, too. That’ll get you into the library over the holiday if you’d like to come see me. Be discreet if you do. You mustn’t let Mrs. Thimbleton catch you inside the Button Factory.”

Oliver grabbed a tray of fudge crumble cookies from the table. “We’re going to my room,” he announced.

“And why should you leave?” Mrs. Glub asked.

“You need coats to go into your room?” Mr. Glub added.

“It’s cold up there,” Oliver explained. “My radiator is dying. It clanks and clunks, but it’s all lies. There’s no heat.”

Mr. Glub gave Archer a knowing smile. “It’s not easy to be the son of a lowly newspaperman.”

Mrs. Glub tapped her foot. “All right. I know you three have much to catch up on. But please, I don’t want you getting any more strange ideas.”

“And we don’t need to be gossiping about things we’re not supposed to gossip about,” Mr. Glub warned. “We’re a Doldrums family. Not a Chronicle family.”

♦ BAD TIDINGS TOWARD MAN ♦

Oliver led the way up the stairs to his bedroom and then out onto his balcony, where they used a metal ladder to climb to the roof. When Archer’s head poked over the ledge, he saw a shoveled pathway across the snowy flat rooftop and a roaring fire in a dented metal bowl.

“We wanted to talk without anyone else around,” Adélaïde explained.

For a moment, Archer stood gazing down into the Willow Street gardens, and then at the Rosewood rooftops stretching in all directions, and finally at the Button Factory smokestacks, rising above all else. He truly was home. But something was different. The house next to Adélaïde’s—Mrs. Murkley’s former residence—was all lit up.

“That’s where the girl I told you about lives,” Oliver said. “She moved in two weeks after you left. Diptikana Misra.”

“But everyone calls her Kana,” Adélaïde added.

“No, everyone calls her cuckoo.”

“She has a silver streak in her hair. That’s usually the sign of a traumatic experience.”

“And we know what that experience was, Archer.” Oliver pointed to the metal bowl. “Do you remember the last time we had a rooftop fire—before the whole tiger disaster? We were tearing up a newspaper to get the fire going, and there was a story about a girl who’d vanished down a wishing well. According to everyone at the Button Factory, that girl was Kana.”

“They said the water inside the well gave her psychic abilities,” Adélaïde said, nodding.

“I don’t believe that part,” Oliver scoffed. “She was strange before that. And now she won’t stop staring at me. I think she wants me to know she’s doing it—like she’s trying to tell me something without using words. It’s creepy.”

“Perhaps she’s trying to say she likes you,” Adélaïde suggested, batting her eyelashes.

Oliver scowled and moved closer to the fire. Archer and Adélaïde followed. Archer told them all about Raven Wood and the rumors of what Mrs. Murkley had done. Their faces dropped when he told them he’d be going back after the holiday. Like Archer, they’d been secretly hoping his parents would let him stay.

“It’s because my grandparents are coming home,” he explained. “My parents even told me to spend more time outside. Something strange is going on. My roommate at Raven Wood, on our last day together, suggested my grandparents might be dangerous, but he wouldn’t say any more. And then earlier today, at Rosewood Station, there was this…” Archer paused. Adélaïde and Oliver seemed to be having an argument with their eyes. “Do you know something?”

Oliver stopped rubbing his hands. “We’re not supposed to tell you, Archer, but we’ve been hearing lots of things. None of it’s good.”

Archer sat perfectly still, staring at his friends. Adélaïde nudged Oliver. He sighed heavily, but continued.

“Everyone in Rosewood is saying the iceberg was a hoax—that your grandparents weren’t actually on one for two years. And the only reason they were on one at all was because they wanted to vanish.”

“We don’t know the details,” Adélaïde said. “But supposedly, before they vanished, your grandparents were doing strange things at the Society. The other members feared your grandparents had gone crazy and were out to destroy everything. There was even an effort to remove your grandfather from the presidency. That’s when your grandparents vanished.”

“Everyone’s thinks they’re dangerous, Archer,” Oliver continued, as Adélaïde dug into her pocket. “They think your grandparents have cursed the city. They’re blaming all of this snow on them.”

Adélaïde handed Archer a bundle of newspaper clippings. His head was reeling and his frown grew deeper as he skimmed headlines: HELMSLEYS’ CURSE! ICEBERG HOAX! KEEP THEM OUT! THE ICEBERG COMES TO ROSEWOOD! He lowered the articles and stared blankly at the mounds of snow, flickering with the firelight.

“This has been going on ever since I left,” he said, his fingers trembling. “Why didn’t you tell me?”

“Your parents told us not to,” Adélaïde explained. “Didn’t they have newspapers at Raven Wood?”

Archer hadn’t seen a newspaper since he’d left. Raven Wood kept some in the mailroom, but Benjamin always sat on them while waiting for him, or knocked them off the table, or took the last one.

“We don’t understand—” Adélaïde continued, but Archer could no longer hear her.

He couldn’t hear anything. The fire went blurry. His friends went blurry. Then everything started spinning. He’d spent two years hoping his grandparents weren’t dead. Two years. If they weren’t on an iceberg, where were they? Why would they let him think they were dead? This couldn’t be right. His grandparents wouldn’t do that. Archer shook himself.

“It’s mostly the Rosewood Chronicle that’s been printing these stories,” Adélaïde was saying. “It’s all they write about anymore.”

“My father won’t print anything until he hears from your grandparents,” Oliver added. “He feels terrible that he got the story wrong the first time. He’s not sure if it was a hoax.”

“What do you mean, he’s not sure?” Archer repeated, almost glaring at Oliver. “Of course it wasn’t a hoax. They sent me a piece of the iceberg. You saw it. Don’t tell me you believe this.”

“Don’t get angry at him,” Adélaïde said. “No one’s saying your grandparents didn’t get onto an iceberg. They’re just saying your grandparents wanted to vanish.”

Archer’s heart was thumping in his ears. Why would his grandparents want to vanish? To want something like that, you’d have to be out of your… His heart stopped.

Archer shot to his feet and shoved the articles into his pocket.

“My grandparents were lost,” he said, moving to the ladder. “Now they’re coming home. That’s all there is to it. Everyone’s going to feel very foolish when my grandparents set the record straight. So I’d suggest you two stop talking.”

♦ A PASTRY IN A GLUB TREE ♦

Archer hurried down the stairs. He poked his head into the Glubs’ great room and saw his parents laughing with Miss Whitewood. Merry spirits danced all around, but they kept their distance from Archer. He continued to the Glubs’ kitchen, which was a complete disaster. He opened the freezer, pushed aside a frozen fish and a pot roast, and there, at the back, saw a large chunk of ice—his piece of the iceberg. The one his grandparents had sent him. He’d left it with Oliver, fearing his mother might pitch it.

Archer pulled it out and went to the kitchen table, resting his head on his fists while his eyes flickered over the frozen hunk. This proved his grandparents were on an iceberg. It didn’t prove it was an accident. And it didn’t prove they were on one for two years. If they weren’t, where had they been? Worse still, in all that time, why hadn’t they sent him a message to let him know they were still alive? A letter. A secret gift. Anything. Were Oliver and Adélaïde right? Was everyone in Rosewood right? Had his grandparents gone round the bend?

Archer didn’t want to return to the party, but the longer he stayed away, the more people might ask where he’d been. He stashed the iceberg back inside the freezer and slowly made his way to the great room. Crazy? Oliver and Adélaïde were sitting on the couch when Archer entered. He went straight to the table of delights, which seemed anything but.

“There you are,” Mrs. Glub said, stepping to his side. “Oliver said you needed a bit of fresh air. Is everything all right?”

Archer’s forced smile betrayed him, drooping into a terrible frown. Mrs. Glub didn’t say a word, but it was clear she knew. She shot Oliver and Adélaïde a sharp eye and then grabbed a plate for Archer.

“You need to eat something, dear,” she said, piling it as high as could be. “Everything seems worse on an empty stomach. Here, take this and have a seat near the windows.”

Archer sat down. Claire immediately joined him. She didn’t say a word, but smiled each time she took and ate a pastry from his plate. Archer could feel Mr. and Mrs. Glub staring at him. He wasn’t sure if he felt more angry or foolish. He didn’t notice that Oliver and Adélaïde had inched to his side.

“We didn’t say we believe your grandparents are dangerous,” Adélaïde whispered.

“Only that it’s obvious something strange is going on,” Oliver added.

Archer stood to flee, but tripped on the gift Claire had tossed over her shoulder earlier. Pastries took flight, and he went headlong into the Glubs’ Christmas tree. The next thing he knew, he was sprawled across the couch with the tree on top of him. The party hushed as he untangled himself from the evergreen and its trimmings.

“I’m sorry!” he said, covered in tinsel, scrambling to gather ornaments and pastries from the floor.

“Don’t you worry!” Mrs. Glub insisted. She swooped in alongside Mr. Glub to right the tree, and though they couldn’t get it to stand straight again, she added, “Look! No harm done!”

Oliver and Adélaïde watched in silence as Archer brought the decorations and pastries back to the tree and began hanging pastries from the branches instead of ornaments.

“What’s wrong, Archer?” Mr. Helmsley asked, stepping in to help him. “I don’t believe the Glubs want pastries in their tree.”

Archer was silent.

“Why don’t you give those here, Richard?” Mrs. Glub said, taking the ornaments. “Yes, I’ll take the pastries, too. Very good. Now, Archer’s had a long day. Look at him. He’s exhausted. Perhaps it’s best he gets a good night’s sleep.”

The Glubs stood on the snowy front steps, watching as Archer followed his parents home. Mr. Helmsley paused outside the front door of Helmsley House. A note with a greasy thumbprint was taped to it. He read it aloud.

“Ralph and Rachel are arriving shortly. Expect them in Helmsley House later tonight or early tomorrow morning.

—Cornelius”

Mrs. Helmsley nearly collapsed on the spot. Mr. Helmsley helped her through the door. She fled down the hall. Archer made for the stairs, his head pulsing, but stopped and turned to his father.

“Why didn’t you tell me what was going on?”

Mr. Helmsley removed his glasses and rubbed his closed eyelids. “I didn’t want you to worry about something that might not be true, Archer. I’m not sure what the truth is, but let’s hope it’s not worse than the rumors.”

Archer shook his head. Worse? “How could it be worse?”

His father didn’t have an answer.

Archer went to his room and lay awake in bed. The moonlight was on his face as his ears searched the darkness, like many ears do on Christmas Eve. But it wasn’t yet Christmas Eve, and Archer wasn’t listening for sleigh bells. He was listening for footsteps. He was waiting for his grandparents.

“Are they crazy?” he mumbled, turning to the window, which glittered with moonlight.

♦ BREWING ♦

Outside Archer’s moonlit window and down crooked Willow Street, across the barren treetops of Rosewood Park and beyond the winding canals that emptied into Rosewood Port, a man with a patch covering one of his eyes ran along a lamplit dock that dipped gently with the waves. The Eye Patch had a wooden case tucked under his arm, and his one visible eye searched the horizon. A darkened ship was entering Rosewood Port. The ship didn’t blow its horn, and its engine was low as it drifted past ice floes, sidled up to the dock, and dropped lines around bollards. Two silhouettes emerged on the deck. The Eye Patch called to them.

“You’re a sight for a sore eye!” His smile faded as he unlatched the wooden case to reveal a bundle of newspapers. “Birthwhistle is brewing a storm.”

CHAPTER

THREE

♦ YEARS OF WONDER ♦

Archer awoke to a bustling and clanking of pots and pans. He rubbed his droopy eyes and hurried down to the kitchen. The stovetop was roaring, and Mrs. Helmsley was dashing this way and that, cooking everything she could get her hands on. Archer kept his distance, fearing she might fry him by mistake. His father sat alone at the table.

“Are Grandma and Grandpa home?” he asked.

Mrs. Helmsley nearly toppled onto the stove.

“Not yet,” Mr. Helmsley replied.

Archer wasn’t hungry, but he didn’t want to meet his grandparents on an empty stomach. He took a plate and a fork and went to the counter, buried beneath eggs and bacon and toast and pancakes and waffles and oatmeal—and his mother showed no sign of slowing.

“I can’t take much more of this,” she muttered, peering over her shoulder as Mr. Helmsley refilled his coffee. “I was at Primble’s Grocery yesterday, and when I got to the counter, they told me to take my business elsewhere! Where are we supposed to get food?”

“They’ll sort out whatever is going on,” Mr. Helmsley assured her. “In the meantime, I’d like them to have their room on the third floor.”

“But we’ve been using it for storage! It’s filled with boxes.” Mrs. Helmsley clicked off the stove and frantically wiped her hands on her apron. “We mustn’t upset them. They might get violent!”

Mrs. Helmsley hurried up the stairs. Mr. Helmsley sauntered after her.

Archer panicked, standing alone in the kitchen. He’d been waiting for this moment for as long as he could remember, but now he didn’t think it’d be anything like he’d expected. Overcome with an urge to retreat to his room, he made for the hall, but froze at the sound of a knock at the door.

All throughout Helmsley House, the animals erupted in joyous furor. Archer had never once heard anything like it.

“It’s time!” a porcupine bellowed. “It is time!”

“They’re home!” cheered a zebra. “How do I look? The stripes, I mean. I should have had them pressed!”

“Shut it, you fool,” the ostrich snapped. “And would someone take this blasted lampshade off my head?”

“Are you sick?” the badger asked Archer. “You look like you’re going to be sick.”

Archer was too fixated on the door to respond, and he was so flustered he didn’t realize he was still clutching a fork as he inched his way toward it.

“We’re gone for nearly twelve years and they change the locks?” came a voice on the other side.

“I’m sure they were changed the moment we left.”

♦ TEA WITH GIANTS ♦

Archer took a deep breath and opened the door wide. He was immediately engulfed in the blinding whiteness of snow whirling into the foyer. He couldn’t see anyone, but heard two voices, filled with laughter. Archer squinted. Two faces emerged. His eyes widened. Archer was staring at his grandparents.

“Why, hello there,” they both said, with smiles so large they might crack lesser faces.

Those three words filled Archer all the way to the top.

“Hello,” was his nervous and quiet reply. “I’m Archer Helmsley.”

“How can you be Archer Helmsley?” Grandpa Helmsley asked. “The Archer I had a brief encounter with many years ago was dressed something like a Christmas tree. And if I’m not mistaken, he also had a peculiar fondness for cucumbers.”

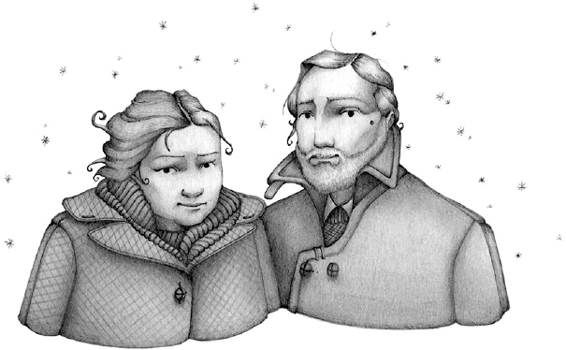

Grandpa Helmsley was as broad as he was tall. His beard, a mix of white and gray, matched his hair, which was pushed back from his forehead. But it was Grandpa Helmsley’s pale green eyes, sparkling with something wild, that held Archer entranced.

“I don’t think he’s that Archer anymore,” Grandma Helmsley said.

Grandma Helmsley was smaller but no less brilliant. Her plump figure was hidden beneath a thick coat and a faded red dress. The warmth beaming from her smile could have thawed the whole of Rosewood.

“He certainly isn’t,” Grandpa Helmsley agreed. Then he pointed to the fork still clutched in Archer’s hand. “You’re not going to… what I mean to say is, that’s a little…”

“Hostile,” Grandma Helmsley finished. “I believe that’s the word you’re looking for?”

“Quite.”

Archer blushed and dropped the fork into his pocket.

“Much better.” Grandpa Helmsley glanced over his shoulder as though they were being watched. “Now would you mind if we stepped inside? It’s no iceberg out here, but it is quite chilly.”

Archer’s grandparents stepped over the threshold and into Helmsley House as though they’d only just returned from a very long walk.

“Best shut the door, dear,” his grandmother said. “Rosewood has many prying eyes.”

Archer closed the door and put his back to it. Stomps and thuds echoed down the stairs.

“Would that be your parents?” Grandma Helmsley asked, hanging her snow-laden coat on a caribou’s antlers.

“They’re fixing your room,” Archer explained, his heart pounding.

“Very good. We did hope to have a moment alone with you.”

“Forks out of the way!” his grandfather whispered, and with a firm hand on Archer’s back, he ushered him down the hall and into the kitchen.

Grandma Helmsley inspected the countertop feast and poked a pancake. “Tea,” she said, shaking her head and taking a kettle to the sink. “Best to begin with tea. Builds an appetite for more.”

“Splendid!” Grandpa Helmsley pulled a chair out from the kitchen table. “And while the water boils, I have a question for you, Archer. Come have a seat.”

Archer wanted to pinch himself as he sat across the table from his grandfather. His grandparents were practically fictional characters to him. He’d read their journals. He knew their tales. They’d crashed planes in the desert and been lost in jungles. But now, here they were, two giants, stepping off the page and into the Helmsley House kitchen.

Grandpa Helmsley leaned forward and clasped his strong hands as though he was about to say something very important. “Tell me, Archer, are the stories true?”

Archer blinked a few times. Stories?

“He means the tigers,” Grandma Helmsley clarified, pulling a tray from a cabinet and setting three cups on it.

Grandpa Helmsley slapped the table, his green eyes sparkling. “The tigers!”

“But more importantly,” Grandma Helmsley said, “that you and two friends put together a plan in the hopes of finding us.”

“We did,” Archer replied. “But that’s not a good story. We failed miserably.”

“Miserably?” Grandpa Helmsley roared. “You mean it failed gloriously!”

“While it was a dangerous thing to have happened,” his grandmother said, lifting the whistling kettle off the stove, “when we heard why it happened, well, we were tickled pink.”

“I was tickled purple!” Grandpa Helmsley said, his eyes still twinkling. “Outrunning tigers? I’ve never heard of such a thing! You’re a Helmsley all the way to the stars, Archer!”

“I can’t imagine Helena was thrilled about it,” Grandma Helmsley said, joining them at the table and pouring everyone a cup.

“No,” Grandpa Helmsley agreed. “But don’t give us this ‘It’s not a good story’ nonsense, Archer. We want to hear all about it. And don’t spare a single detail.”

Archer had never imagined his grandparents would be eager to hear his story, especially with so many more important things to discuss. When he’d finished telling it, his grandparents were silent. Grandpa Helmsley’s whole face had welled up. Grandma Helmsley patted his shoulder gently.

“Don’t let your grandfather’s scruffy outsides fool you, Archer. Inside, he’s as soft and sweet as a caramel.”

Grandpa Helmsley chuckled and cleared his throat. “Forget the caramel, Archer. It’s only that, what I mean is—look at you! You’re completely grown! And we missed it.”

“Now you’re talking nonsense,” Grandma Helmsley said. “He still has plenty of growing up to do. That’s not to say you’re underdeveloped, Archer.”

Grandpa Helmsley sized him up. “Tad short for your age. And skinny like your father. But with a bit of elbow grease, you’ll sprout like an oak! The Society will help with that. Once you’re a—”

“Let’s not get ahead of ourselves,” Grandma Helmsley urged.

Grandpa Helmsley sipped his tea. “Yes, lots to sort out first.”

“Like the iceberg?” Archer asked hesitantly.

Grandpa Helmsley leaned back in his chair and folded his arms. “What have you heard, Archer?”

“Lots of things.”

“People do love to talk.” Grandma Helmsley shook her head in disgust. “Especially when they’ve not the slightest idea what they’re talking about. Makes them feel clever.”

“They’re saying you wanted the iceberg to happen,” Archer explained. “They’re saying you wanted to vanish. They’re saying you went—” He stopped, not wanting to tell his grandparents the part about them being unhinged. But it was clear they already knew.

Grandpa Helmsley reddened liked a stubbed toe. “It’s complete rubbish, Archer. You mustn’t believe a word of it.”

“So what happened? How did you survive the iceberg?”

“Well,” Grandpa Helmsley said, running his fingers through his beard. “While I can promise we were on an iceberg, Archer, it wasn’t for two years. It was more like, three days. Give or take.”

“Three days? So where were you all this—”

Archer fell silent. His mother had suddenly appeared, standing frozen by the kitchen door, staring at his grandparents’ backs the way one typically stares at ghosts. Grandma and Grandpa Helmsley spun around.

“HELENA!”

It was only one word, but even that seemed too much for her. She tried to respond, but instead glugged like a jug of water held upside down. And she went on glugging until eventually, she glugged, “You’re dead!”

To be fair, it probably wasn’t what she’d planned on saying.

“I’m dead?” Grandpa Helmsley repeated, winking at Archer as he glanced himself over. “Well, I do wish someone had told me sooner. That’s the sort of thing people like to know. It’s odd, though. I don’t feel dead. Do you feel dead, Rachel?”

Mrs. Helmsley flushed. “That’s not what I… I didn’t mean to… I apologize if I—”

“Now, don’t you apologize, Helena,” Grandma Helmsley said, giving Grandpa Helmsley an eye that said many things. “Ralph’s having a bit of fun with you, is all. It’s as much a shock to us as it is to you.”

Archer wasn’t sure if that was possible. He’d never seen anyone look more shocked than his mother did. And he guessed her shock would not quickly vanish.