Полная версия

Edge of Extinction

“It’s been almost five years,” Shawn pointed out. “The odds that you are going to find out anything at this point are low.”

“Does that mean you don’t want to see the information I got?” I asked, trying hard to keep a straight face.

“I didn’t say that,” he grumbled, and I grinned, knowing I’d won.

“You should have at least told me you were going topside so I knew to send the marines’ body crew out for you if you didn’t make it back,” Shawn grouched. I made a face at him. The marines’ body crew was a standing joke between us. There was no such thing as a body crew in North Compound, because what lived above us didn’t leave bodies behind. The crackling of the PA system signalled that announcements were over and I turned my attention back to the front of the classroom.

“Miss Mundy,” Professor Lloyd called out, and I jumped. “I can only assume you were late because you were spending your time studying for our literary analysis today. Please stand,” he said, not bothering to look up from his port.

“Busted,” Shawn hissed.

“You too, Mr Reilly,” Professor Lloyd said. Someone sniggered, and my face turned bright red as I stood. Shawn grumbled something incoherent, but he stood as well.

“All right, Miss Mundy,” Professor Lloyd said, glancing down at the port screen in front of him. “If you wouldn’t mind giving the class an explanation of the similarities between the events that transpired in Michael Crichton’s ancient classic Jurassic Park and the events that have transpired in our own history.”

“Similarities?” I asked, swallowing hard. I’d just finished reading the novel the night before, so I knew the answer, but I hated speaking in public. Facing the pack of deinonychus again would have been preferable. I wasn’t sure what that said about me.

“Yes,” Professor Lloyd said, a hint of annoyance creeping into his voice. “Quickly, please. We are wasting time that I’m sure your classmates would appreciate having to work on their analyses.”

“Well,” I said, keeping my eyes on my desk, “in Mr Crichton’s book, the dinosaurs were also brought out of extinction.” I glanced up to see Professor Lloyd staring at me pointedly. He wasn’t going to let me get away with just that. Clenching sweaty hands, I ploughed ahead. “The scientists in the book used dinosaur DNA, just like our scientists did a hundred and fifty years ago. And just like in the book, our ancestors initially thought dinosaurs were amazing. So once they had mastered the technology involved, they started bringing back as many species as they could get their hands on.”

“Thank you, Miss Mundy,” Professor Lloyd said. He turned to Shawn, who had propped one hip on his desk while he was listening to me, the picture of unconcerned boredom. Professor Lloyd noticed too and frowned. “Mr Reilly, if you wouldn’t mind explaining the differences between Crichton’s fiction and our own reality?”

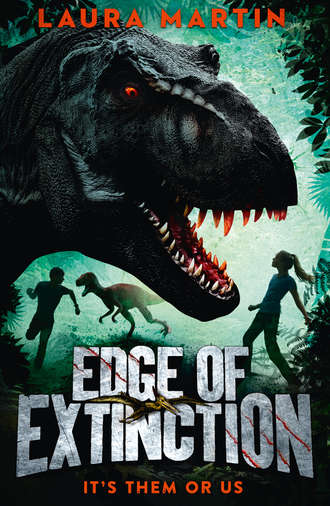

“Sure,” Shawn said, with a wide grin. “Well, the obvious one is the size of the dinosaurs, right? I mean, ours are gigantic. Almost twice the size of the ones that Crichton guy talks about.”

“That’s correct,” Professor Lloyd said, addressing the room. “As Mr Reilly so eloquently put it, that Crichton guy based his dinosaurs on the bones displayed in museums and pictured in Old World biology books. What Crichton didn’t take into account was how different our world was compared with the dinosaurs’ original harsh habitat. Chemically enhanced crops, gentler climate and steroid-riddled livestock made them grow much larger than their ancient counterparts.”

“You can say that again,” Shawn said, and the class chuckled. I didn’t laugh. The memory of my close call with the pack of deinonychus was still too fresh. They’d seemed massive, and they weren’t even one of the bigger dinosaurs. The compound entrances were set in a small clearing bordered by fairly thick forest, which made it impossible for the larger dinosaurs to get too close.

“Anything else, Mr Reilly?” Professor Lloyd asked, a hint of annoyance back in his voice.

“Yeah,” Shawn said. “The people in the book didn’t have them as pets, on farms, in zoos, or in wildlife preserves like we did before the pandemic hit. They were mostly kept to that island amusement park thing.”

“And why is that important?” Professor Lloyd prompted.

Shawn rolled his eyes. “Because when the Dinosauria Pandemic hit our world and wiped out 99.9 per cent of the human population, it was really easy for the dinosaurs to take over. Which is why we now live in underground compounds, and they live up there.” He pointed at the ceiling.

“For now,” Professor Lloyd corrected. “Our esteemed Noah assures us that we will be migrating aboveground as soon as the dinosaur issue has been resolved.”

“They’ve been saying that for the last hundred and fifty years,” I muttered under my breath, just loud enough for Shawn to hear. He flashed a quick grin at me. The different plans to move humanity back aboveground had spanned from the overly complicated to the downright ridiculous, but each time a new plan was brought up, the danger of the dinosaurs was always too great to risk it.

“So in summary,” Professor Lloyd said, motioning for us to have a seat, “the scientists of a hundred and fifty years ago were unaware that by bringing back the dinosaurs, they were also bringing back the bacteria and viruses that died with them. And as you all know about the disastrous devastation of the Dinosauria Pandemic, I will stop talking to give you as much time as possible to complete your literary analysis. You may access the original text on your port screens.”

I glanced down at my port screen, where the text had just appeared. Professor Lloyd was right – we all did know about the disastrous effects of the Dinosauria Pandemic; we lived with them every day. I tried to imagine what it had been like back then. The excitement as scientists brought back new dinosaur species daily. The age of the dinosaur had seemed like such a brilliant advance for mankind. How shocked everyone must have been when it all fell apart so horribly and so quickly.

The Dinosauria Pandemic had hit hard, killing its victims in hours instead of days like other pandemics. It had spread at lightning speed, not discriminating against any race, age or gender. I could just imagine how shell-shocked the few survivors must have been, those who’d been blessed with immunity to a disease that should have been extinct for millions of years. They must have thought the world was ending. And I guess, to some degree, it was.

One by one, the countries of the world had gone dark as news stations went off air and communication broke down in the panic that followed. I wondered if anywhere else had fared better than the United States. Were there underground compounds sprinkled throughout Europe? Asia? Africa? Were people thousands of miles away huddled together thinking they were the last of the human race just like us? I hoped so, but I doubted it.

The United States had got lucky to avoid extinction. With no formal government left standing, one man had stepped up to rally what was left of humanity. He’d called himself the Noah after some biblical story about a man saving the human race in a big boat called an ark. He’d arranged for the survivors to flee into the four underground nuclear bomb shelters located in each corner of the United States. And once we were out of the way, the dinosaurs quickly reclaimed the world, and we’d never been able to get it back.

I pulled up my copy of Jurassic Park on my port and flipped through the pages, looking for something I could use in my analysis. I’d hated reading Crichton’s book, and I doubly hated having to write about it. His descriptions of life topside made my insides burn with jealousy. It wasn’t fair that one generation’s colossal mistake could ruin things for every generation to come.

I was the first one to finish the analysis. I was always the first one to finish an analysis. Poor Shawn was sweating, his tongue protruding from compressed lips as he scribbled furiously. When the bell rang ten minutes later, he finally walked up to plug in his port and I could tell from the look on his face that it hadn’t gone well.

“Miss Mundy,” Professor Lloyd called out just as I was slinging my bag over my shoulder to leave, “a moment, please.”

My heart sank, but I dutifully filed up to wait by the side of his desk as the last few students plugged in their ports and left. He gazed at his own port, moving his finger down the list of students, ensuring that all of our assignments had been uploaded for him to grade before turning to me with a frown.

“It didn’t go unnoticed that this was your third tardy in three weeks, Sky.”

“I’m sorry, sir.” I hung my head.

“I believe you know what to do with this,” he said, pressing a button on his port screen. Immediately my own port vibrated and I glanced down to see a work detail form filling my screen. There was a place at the bottom for a parent’s digital signature, but Professor Lloyd had crossed out the word Parent and instead typed the word Guardian.

“Yes, sir.” I slipped the paper into my pocket. It would get signed for the following day, but I would be the one doing the signing.

I bolted for the door, and almost ran headfirst into Shawn.

“Whoa!” he exclaimed, catching my port screen deftly before it could hit the concrete and shatter, again. “Where’s the fire?”

“No fire,” I scowled, taking back my port. “Just another stupid work detail.”

“Work detail is a character-building experience,” he said sarcastically.

“Then why don’t you serve it for me if they’re so great?” I asked.

“Because my character is already flawless,” he grinned. “It would be a waste of our compound’s precious resources.”

I gave him an elbow to the ribs as we headed towards science class. We paused in the hallway to let the kindergarteners totter past us on their way back from the library. Shamus waved at us shyly and I noticed Toby Lant slumped at the back of the line, his head down. He had the greasy, unwashed appearance of a kid whose parents didn’t keep track of how often he bathed and a hollow look that I’d seen in the mirror a bit too often. My heart hurt for him, even if he had been bullying Shamus.

“Do you have a lunch ticket?” I asked Shawn as we watched the kids’ progress down the hall.

“I have my pack for the whole week. Why?” I snatched the entire pack from him before he had them halfway out of his pocket and hurried over to crouch by Shamus. Tucking the lunch tickets into his hand, I whispered in his ear. He smiled nervously at me but nodded. After a quick ruffle of his hair, I hustled back to join Shawn.

“Why did you just give Shamus my lunch tickets? Not that I’m complaining, but I was planning on eating at some point this week.”

“I don’t think you’ll starve to death,” I grinned. When Shawn had stopped growing at five feet one inch, he’d decided that what he lacked in height he could make up for in bulky muscle. I doubted that a few missed meals would affect him. “Besides, you know your aunt could get you more. Just tell her you lost them. Shamus needed to buy lunch for his new friend, Toby.”

“Does Toby know he’s Shamus’s new friend?” Shawn asked. I shrugged. I would have given Shamus my lunch tickets, but I had lost those last week for not reporting to work detail on time.

Shawn must have understood, because he didn’t say anything else about it as we ducked into our science classroom. This was my favourite class of the day because the room had a domed skylight ceiling. Of course, the Plexiglas of the skylight had been patched, repaired, barred over and reinforced in so many places that it didn’t really afford much of a view of the outside world any more, but the natural light still managed to filter through, and it was a relief after the harsh fluorescents. Humans weren’t meant to live their lives underground, and sometimes my skin practically itched for the sunlight.

Soon, though, even this little piece of the outside world would be taken away when the workers began concreting over the glass. Noah had insisted that we fortify all topside surfaces. This new decree seemed silly to me. The dinosaurs had never penetrated the barrier that separated our world from theirs, so why waste the resources? Unfortunately, no one asked my opinion on the matter, especially not the most powerful man in the world.

I glanced around at the rows of plants lining the walls and frowned. They would all be dead soon unless we brought some grow lights up from the farming plots. The rest of my class filed in, all eight of them. Professor Murphy moved to the front of the room to begin trimming back a fern whose leaves reminded me of Shawn’s hair – floppy and out of control. Shawn sat down beside me and slid a bag of crackers on to my desk. He knew that I’d have skipped breakfast in order to make it out to the maildrop. When I went to thank him, I saw that he was working furiously on the homework from the day before. The crackers had the slightly chemical taste that most compound food had, but I savoured every one, especially now that Shawn’s lunch tickets were gone. As the class began, I couldn’t help but wonder if I would have resorted to stealing lunch tickets if I hadn’t had a best friend who was willing to share.

Shawn and I once joked that the entirety of our education in North Compound could be summed up into two lessons. Lesson one was some variation of a history lesson about how the human race had found itself living in underground compounds. Today’s English lesson with Professor Lloyd had fallen under that heading. Lesson two was how to actually survive in the compound. Professor Murphy’s lecture landed squarely in the second category. She started discussing the finer points of artificial turnip germination and I zoned out immediately. Since the majority of the supplies and food for the compound were generated within the compound, lessons like this were common, but I just couldn’t get excited about turnips. From the way Professor Murphy kept stifling yawns, I had a feeling that she felt the same way.

Seven hours later, when the last bell of the day finally rang, I made my way through the crowded south tunnel to find Shawn. Being crowded was a good thing. North Compound had started off with just twenty survivors. Luckily the immunity that had saved those original twenty from the Dinosauria Pandemic seemed to pass on genetically in most cases, so our population levels were slowly climbing. I think we were at ninety-five last I’d heard. After years of teetering on the edge of extinction, the human race was making a slow but steady comeback.

I tried to ignore the fact that none of my classmates felt the need to include me in their easygoing conversations. I was an island in a sea of chatter and laughter that I wasn’t allowed to be a part of. Some of these kids’ parents had written petitions to have me banned from attending school altogether. Luckily for me, all those petitions failed. In a community grounded on principles of collaboration and equality, even the daughter of a traitor was owed an education. I wouldn’t want to be part of their stupid conversation anyway, I thought as I ducked my head and made my way into the library to find Shawn.

A library hadn’t been on the original engineer’s design plans for the compound, although they’d thought of almost everything else. There were huge spaces on the bottom level equipped with water lines and grow lights to cultivate plants, a water and electrical system that could function without any outside power or input, and even a livestock area for animals like cows or pigs. But those stalls had long ago been turned into offices and storage units since, in the chaos of fleeing the topside world, no one had thought to grab any. Now the poor creatures were extinct. A cow didn’t stand a chance against a dinosaur. Which wasn’t saying much. Most things didn’t stand a chance against a dinosaur.

I found Shawn near the back of the library. A bench seat had been chiselled out of the concrete, and he sat in the nook, his port screen in hand, brow furrowed in concentration.

Sitting down beside him, I peered over his shoulder. “What are you working on?”

“My written analysis from this morning.” Shawn grimaced. “It was apparently so terrible that Professor Lloyd said he’d let me take it home to fix.”

“He posted the grades already?” I pulled out my own port screen, but before I could access the grade account, Shawn was shaking his head.

“Not yet,” he said, his face flushing a little.

“Oh.” I nodded, understanding. Shawn lived with his aunt, who was a council member in North Compound. And even though the law stated that no citizen should have more than another, that we share every resource available, somehow government officials still ended up with the best apartments, extra allotment tickets for food, and the most opportunities.

“I didn’t ask him to.” Shawn shrugged sheepishly.

“But he wants to get on your aunt’s good side, right?”

“Pretty much,” Shawn said. “I think he’s petitioning for funding for the library or something at the next council meeting.”

I leaned my head back against the cool concrete of the wall and stared up at the ceiling of the tunnel.

“I wouldn’t take the help,” Shawn said, “but if I don’t get my grades up, I’m going to be stuck with a work assignment in sewer detail.” He was right. Our grades weighed heavily in the final decision on work assignments when we turned fifteen. It wasn’t like better jobs got better pay. We all worked for free because it was our responsibility to do so, and because if you didn’t work, you didn’t eat. But the better your grades, the better the job you were likely to be assigned. Shawn really had nothing to worry about. With an aunt as high up the chain as his was, I doubted sewer detail was in his future. However, even with my good grades, I was disliked enough that it was a possibility for mine.

“It’s fine,” I said, turning to smile at him. “It’s not your fault everyone likes to suck up to your aunt.”

“I wish your aunt had transferred to North Compound instead of mine.”

“Shawn Reilly,” I said, “stop wishing fictional relatives on me. I’m fine.”

“I asked her again last night about getting you out of there, but she brushed me off and gave me the same old story about rules and regulations. It’s not fair.” I agreed, but telling Shawn that would just make him feel worse than he already did.

“It’s OK,” I said. “You deserve good things.” I’d never met anyone with a bigger heart than Shawn Reilly, and without his friendship my life in the compound would be worse than miserable.

“So do you,” he scowled, and the way it wrinkled his forehead and made his mouth pull down at the corners was so familiar that I had to smile.

“I can think of a way you could make it up to me,” I said slyly, glancing at him from the corner of my eye, “if the guilt is really eating you up inside.”

“So I take it your mail run this morning was a success?” he asked drily, putting his port screen away. Shawn knew the purpose of my mail runs, and he knew full well what I needed him to do for me. But he liked to be asked. It was small payment for asking him to break the law for me on a routine basis.

I grinned wickedly. “My best friend gave me this great scan plug, and I put it to good use.”

“How long did it take to upload?” Shawn asked.

“About five seconds,” I said.

He nodded. “Not bad.”

“Any longer and you might have had to send the body crew out after me,” I admitted.

Shawn froze. “What happened?”

“A deinonychus pack.”

“What kind are those again?” he asked, his forehead wrinkling in confusion.

I groaned in exasperation. For someone who lived in an underground compound because of the millions of dinosaurs stomping around overhead, Shawn knew next to nothing about them. He preferred to spend his time tinkering with anything and everything mechanical.

“They travel in packs, and have huge claws on their hind feet for ripping their prey open.”

“They sound like loads of fun,” Shawn drawled. “I can see why you’d want to go running around with them.”

I rolled my eyes. “You’re impossible.”

“No,” Shawn countered, “I’m just not obsessive about researching the ugly things like some people I know. Let me guess, you already updated your journal?”

I kicked him hard in the shin, glancing around the library shelves to make sure they were deserted.

“Youch,” he grimaced, rubbing his shin. “That wasn’t really necessary.”

“I disagree,” I snapped. Shawn knew I had a strict rule about never mentioning my journal where we could be overheard. “Now are you going to help me or not?”

“Of course,” he grumbled, standing up and slinging his bag over his shoulder. “I can’t come tonight, though; my aunt needs my help with the new baby while she goes to a meeting.”

“Tomorrow, then?” I asked.

“Sure.” He nodded. “We’d better get going. Your work detail starts in fifteen minutes.”

“Right,” I said. Shawn turned towards the tunnel that would take me home, even though it was out of his way. After leaving the library, we turned left and walked for about five minutes before we came to a hub tunnel that split off in five different directions. Once upon a time there had been signs marking which way things were, but they had long ago broken and worn away and no one had bothered to fix them. These tunnels were our entire world, and we knew them well.

“See you tomorrow,” Shawn said, heading down the tunnel second to the left, while I took the tunnel straight ahead. “Be on time!” he called over his shoulder.

I broke into a jog and didn’t slow down until I hit the entryway to the Guardian Wing. Unlike the habitation sector, the Guardian Wing was built in the part of the compound that had originally been the rock quarry; its walls and rooms were cut out of granite instead of crafted out of smooth, man-made concrete. I still remembered that scary night five years ago when I’d first seen this section of the compound.

“This is your new home,” General Kennedy had told my seven-year-old self after escorting me past the guardian on duty to a tiny room where a small bed and mattress sat along the back wall. “Lights go off at nine o’clock sharp, and you will be locked in at night.”

“Locked in?” I’d asked.

“The Guardian Wing is for those who don’t have a place with the rest of the community. The doors are locked for safety purposes. Show some gratitude that the Noah allows you to stay here. You are a burden on our society.” He’d turned and walked out, locking the door behind him. I’d looked around the tiny room and my chest had ached with homesickness for the little apartment in the seventh sector my dad and I had shared. And then the lights had gone out. I’d sat down on the icy floor, too exhausted to attempt to find the bed, and cried myself to sleep.

The sound of something scratching at my door had woken me, and I’d sat bolt upright in a panic. Before I could scream, my door had opened, and a short, stocky boy had been silhouetted in my doorway, an odd flashlight clutched in his hand. Holding a finger to his lips to keep me quiet, he’d eased the door shut behind him. He’d tiptoed over and looked down at me, sitting among the meagre supplies Kennedy had given me.

“How did you get in?” I asked, blinking tear-swollen eyes.

“Lock picks,” he said, holding up two small metal sticks. “I’m Shawn.”

“I’m Sky,” I said, wiping my eyes on the sleeve of my grey compound jumpsuit. “Why are you here?” I’d meant my room, but he misunderstood, dropping down to sit opposite me on the cold stone floor.

“Same reason you are,” he said. “Orphaned when my parents died in the tunnel collapse two months ago.”

I’d wrapped my arms protectively around myself and felt my chin jut out defiantly. “My dad isn’t dead.”