Полная версия

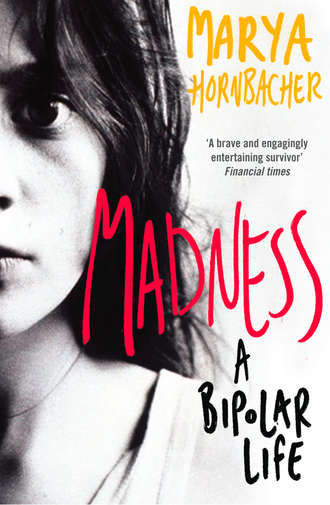

Madness: A Bipolar Life

I crawl out of bed and slide out the drawer from the bed stand, turn it over, and untape the baggie of cocaine underneath. Kneeling, I tap lines out onto the stand, lean over, and snort them up with the piece of straw I keep in the bag. I sit back on my knees and close my eyes. There it is: the feeling of glass shards in the brain. I picture the drug shattering, slicing the gray matter into neat chunks. My heart leaps to life as if I’ve been shocked. I open my eyes, lick my fingers and the straw, and put the baggie away, replacing the drawer. I lift off, the roller coaster swinging up, clattering on its tracks, me flying upside down.

Humming, I take a shower and dance into my clothes—a ridiculously short skirt with a hole that exposes even more thigh, black tights, a ripped-up shirt. I pack up my book bag, pull out another baggie, pills this time, from the far corner of the desk drawer. I select a few and put them in my pockets, then spring into the day, a gorgeous day, a good day to be alive. Good morning! I call, sitting down at the table, bouncing my knee at the speed of light.

You’re in a good mood this morning.

I am! I am indeed. I watch my father scramble eggs, and then panic: what am I thinking? I can’t eat that. I leap to my feet. Gotta go! Can’t stay to eat! I punch my father on the arm as I run out the door.

But you need to eat! he calls after me. Get back here! You can’t leave dressed like that!

Bye, I call, setting off down the street, my book bag banging against my leg. The trees are in bloom. The sun is pulsing. I can feel it touching my skin. My skin is alive, crawling. Suddenly I stop. My skin is on fire. I drop my book bag, start rubbing my skin. Get it off! I am dancing around in the middle of the road. There are bugs on my arms, crawling up my neck, crawling on my face and into my hair, Get them off me! Where the hell are they coming from? I fall onto the grass at the side of the road, rolling, trying to get them off. My hair tangles and dirt grinds into my clothes. Finally the bugs are gone. I stand up, smooth my hair, and, much better now, skip down the road to school. It’s so annoying when that happens. But I’m not about to give up the cocaine.

No one knows about the powders, the pills, the water bottle filled with vodka that I keep in my bag. My friends are good girls. I am a tramp. I don’t know why they bother with me. I slouch in my seat in the back of the room, my arms folded, hiding behind my hair. The teachers are idiots. I hate their clothes, their thick, whining Minnesota accents, the small-town smell that clings to them: dust and tuna casserole. This whole town is a bunch of suburban clones, blond, blue-eyed, dressed in tidy matching clothes. Everyone looks the same. Everyone will wind up married, living in a mini-mansion with a sprawling, manicured lawn. There’ll be cute little identical children, and the men will golf and drink and slap each other on the back, old chum, and the women will lunch at the country club and listen to lectures about the deserving poor, the homeless children downtown. They’ll shake their heads with concern and volunteer for the PTA and at the Lutheran church, collect bad art and vote Republican, and hate people like me.

I have to get out of this town.

After lunch, I lean over the toilet in the bathroom stall and throw up. I wipe my mouth, scrub my hands, sniffing them to make sure they don’t smell, wash them again, wipe them dry, look in the mirror, reapply my lipstick, study my face. I brighten my eyes, paste on a smile, and go back out, where the kids teem down the hall.

These are supposed to be the best years of my life.

I fail home economics. I refuse to sew the stuffed flamingo. I question the necessity of learning to make a Jell-O parfait. I blow up an oven—I forget to put the nutmeg in a baked pancake, and when it’s already in the oven, I toss in a handful as an afterthought, setting the entire thing on fire.

I persecute the art teacher. I sit in detention until dark, day after day. When I’m not in detention, I’m running around the newspaper room, putting together what I’m sure is an incendiary tract that’s designed to infuriate everyone who reads it. I am ducking under my desk every half-hour, sucking up the vodka in the water bottle. I am in the library, snorting cocaine off Dante, back in the stacks.

I gallop down the hall at school in a state of absolute glee, dodging in and out between the other kids, shouting, “Hi!” to the people I know as I pass. They laugh. I am hilarious! “You’re crazy!” they call. I am crazy! I’m marvelous! I’m fantastic! The day is fantastic, the world!

“Slow down!” a teacher shouts after me. “No running in the halls!”

I turn and gallop back to him. “Not running!” I shout joyfully. “Galloping, as you can plainly see!” I gallop off.

At the end of the hall, I crash into the wall and bounce back into the circle of my friends who are clustered around my locker. “Isn’t it wonderful?” I cry, flinging my arms wide, picking them up in the air.

“Now what?” Sarah laughs.

“Everything! Absolutely everything! You, today, all of it, wonderful! Amazing! Isn’t it grand to be alive?”

“Weren’t you, like, all freaky and twitchy this morning?” asks Sandra. I pound down the stairs, my legs are faster than speed itself! Tremendous! Spectacular speed, splendid speed, splendiferous speed! I reach the bottom of the stairs and go skidding across the hall. My friends are laughing. I make them happy. I make them forget their horrible homes. I love them, I love them hugely, they are absolutely essential, I would absolutely die without them.

“No!” I shout, “I wasn’t freaky! Well, if I was, I’m certainly not anymore, obviously!” I skip backward ahead of them as we go to lunch. I grab an ice cream sandwich and a greasy mini-pizza. I will be throwing these things up after lunch, obviously, wonderful! I laugh with delight, pleased with myself. “Aha!” I shout, and the people in the line ahead of me crane their necks to look. “Hello, all of you!” I shout, waving, “it’s a beautiful day!” Someone mutters, “She’s crazy,” and I don’t even care, everyone’s entitled to his opinion! That’s the way of the world! We are a world of many opinions, many beliefs! To each his own!

My friends and I move in an amoeba-like cluster over to an open table near the windows and sit down. We munch away on our lunches, chatting, and I chatter like a ventriloquist’s dummy, and all of us laugh, and then I start crying, but right myself quickly. “Enough of that!” I say, wiping my nose, making a grand gesture, “all’s well!” And everyone is relieved, and I have a brilliant idea! I pick up my personal pizza and whip it across the room like a Frisbee! And it lands perfectly in front of Leah Pederson, whom I hate! “Yes!” I shout, triumphant, and the entire lunchroom is laughing, and it’s time to go back to class. I gather my books and my friends and walk calmly down the hall and fling myself into my chair with an enormous sigh.

This time I will be good, I promise myself. This time I won’t make a scene. My heart pounds and I feel another round of hysterical laughter welling up in my chest. I press my face between my hands. I will hold it in. I won’t get detention. I won’t get kicked out of class. I won’t punch Jeff Carver. I won’t turn over any desks, or throw any chairs. I sit up in my chair, open my notebook, click my pen. I stare straight ahead at the teacher who is shuffling papers and handing them out. I will be good. I will, I will, I will.

I SIT IN THE OFFICE of my mother’s shrink. The air circulates slowly in the room. I turn in circles in my swivel chair. To my right, through the window, two floors down, is the parking lot and the sunny, empty afternoon. A small man with square black glasses and gray hair sits kicked back in his leather office chair, watching me.

“What would you like to talk about today?” he asks.

I keep turning in circles. I shrug. “What do you want me to say?”

“What would you like to say?”

I look out the window, count the red cars in the parking lot, then the blue. “I don’t have anything to say.”

We sit in silence. The minutes tick by.

“What are you thinking right now?” he asks.

“Nothing particular.” I turn to face him. He scribbles something on his yellow notepad.

“What are you writing?” I ask.

He gazes at me. “What do you think I’m writing?” he asks.

“I haven’t the faintest idea,” I say.

He scribbles some more.

“Are you supposed to be helping me?” I ask.

“Do you think you need help?”

I turn to face the window again. “I don’t know.” From the corner of my eye, I see him write something down.

“You seem very upset,” he says thoughtfully.

Startled, I look at him. “I’m not.”

He tilts his head to the side. “You’re very angry, aren’t you?” he says.

I laugh. “You’re very perceptive, aren’t you?” I say. He writes it down.

Seven red cars, six blue. The day is still. The branches of the trees don’t move. We sit in silence. I turn circles in my chair.

HE’S A FREUDIAN therapist. When he speaks, he asks me about my mother, about my dreams. I wait for him to tell me what’s wrong with me, why I snap into sudden, violent rages, and shut myself in my room with the dresser backed up against the door for days, and disappear in the middle of the night, and stay in constant trouble at school. Why is it that my moods are all over the goddamn map? How come I’m terrified all the time? He sits silently, watching me, saying nothing, fixing nothing. I give up.

He isn’t looking for eating disorders or drinking or drug use. He isn’t looking for mental illness. In truth, he isn’t looking for much at all. One day he slaps his notebook shut. What’s wrong with me? I ask. Am I crazy? I don’t ask that. I think I know.

His wise and considered opinion is that I’m a very angry little girl.

WORD GETS OUT at school that I’m seeing a psychiatrist. My friends avoid the subject. But other kids whisper about it when I come into the room, kids I don’t like and who don’t like me, the rich kids and the snobs. One of them, egged on by the others—Go on, ask her—comes up to me: Is it true you’re, like, crazy?

No, I say, looking down at my desk.

Then why are you seeing, like, a psychiatrist? Isn’t that for crazy people? Isn’t it? Come on, admit it!

I don’t answer. I scribble so hard in my notebook that my ballpoint tears the page. They laugh. I’m a freak, and everyone knows it, including me.

Then suddenly it hits, a massive, crippling headache. My migraines are coming on nearly every day. I stagger into the nurse’s office and collapse on a cot, curled up in a ball with a pillow over my face. The nurse calls my parents. Back home, I lie in the dark, blinds drawn, rabid thoughts and images zipping through my brain, flashes of blinding color and light. I lie there, shivering and sweating as the pain clenches my skull, nearly paralyzed with fear at the fierce throbbing behind my eyes.

My father opens the door slowly, shuts it quietly behind him. I wince at the deafening noise. The bed sags and he leans over me.

“Here,” he says softly. He lays a wet washcloth over my eyes. “How is it?” he asks.

“Horrible,” I whisper.

“I’m sorry,” he says. He lays a hand on my shoulder. “It will go away soon.”

The bed squeaks as he gets up. The door thunders shut behind him. I press my hands to my head.

They take me to doctor after doctor. No one knows what’s wrong. They give me medication, try biofeedback, tell my parents they don’t know. My parents tiptoe through the house, confused, scared. They don’t know what this onset of violent headaches means. Neither do the doctors. Neither do I.

DEATH WOULD BE SO quiet. I hide in the bathroom with an X-Acto knife, making tiny cuts, crosshatch patterns in my thighs. Nothing deep. It helps relieve the pressure, focus the thoughts. I take a sharp breath and breathe out slow. The blood beads along the cuts. I sop it up with Kleenex, the red spreading out over the tissue. I bleed. I’m alive.

AND THEN it’s dinner and my father’s screaming, and my mother’s cold and icy and cruel, and they’re yelling at me and I’m yelling at them—the crazies rise up in my chest and I run away from the table, the rage welled up so far it presses at the back of my throat. I can taste it. My father chases me, hollering. I shriek and run away. We stand face to face, screaming, his face is twisted and I can feel that my face is twisted and I hate him and his craziness and I hate myself for mine, and my mother gets up, walks down the hall, and slams the bedroom door.

My father and I scream each other down until we are exhausted, completely spent. We stand there panting.

“Say,” my father says brightly, perking up. “Want to play Yahtzee?”

“Sure!” I say. And we sit down to play, laughing and having a wonderful time.

AFTER SCHOOL, I open our front door and step inside. The first thing I see is my father, lying on his side on the couch. Light streams in through the long windows, and it takes my eyes a moment to adjust.

I drop my book bag. “What’s wrong?” I say to him from across the room. I don’t want to know what’s wrong. I’m tired of this. You never know which father is going to show up.

He curls up and wraps his arms around his knees.

“I don’t know, Marya,” he says, and starts to cry. “I really don’t know.”

I stare at him flatly. I want to run over there and kick him and pound him until he gets up. When he gets like this, I feel like I am drowning. The hands of his sadness close around my throat and I can’t breathe. I have run out of the enormous love he needs to be all right.

“You know those afternoons,” he asks, drawing a shaking breath, “where you’re just going along, doing fine, and then afternoon comes and it feels like you just got the wind knocked out of you and everything is wrong?” He sighs and slowly pushes himself up so he’s sitting upright. His shoulders are slumped. “That’s all,” he says. “It’s just one of those afternoons.”

We are silent for a minute. Then he lies back down on the couch.

I should say I love him. I should say it will all be all right. But it won’t.

I walk down the hall to my bedroom. I lie down on my side and stare at the wall, the blue-flowered wallpaper next to my nose. Despite my best efforts, I start to cry.

I know those afternoons.

Escapes

Michigan, 1989

I’m sitting in the study lounge, it’s five A.M., and I have no idea how many nights or days have gone by since I last slept. I’m starving, I’m writing, I can’t stop, don’t want to stop, don’t want to eat, I am possessed by words. I’m at boarding school, an art school where students not yet eighteen spend ten hours a day, six days a week, training, practicing, studying harder than even seems possible, possessed by a desire to make it, to succeed, and I’m surrounded by open books on the study lounge table, my typewriter pouring out a short story, a paper, another, another. I am no longer a fuckup, I’m going to make it, I’m going to ace my classes, I’m going to stay awake forever if I have to, just so long as I write this, whatever it is.

Through the window that looks out over the snowy campus, the light is coming up. The snow is lit a violet-blue, the horizon’s a red-orange line. I sit back in my chair, my body buzzing, this heavenly hum in my head. Paper in stacks on the table. I’m ready for workshop, a fistful of stories in my hand. I’ve read everything for class that I was supposed to and then some. Physics thrills me, math confounds me, the German teacher despairs, but the English teacher, the writer-in-residence, the staff writers who pound us with work, they pull me aside and say: Read it, write it, don’t stop, you’ve got it, you’re going to make it. The magic words, the promise. The hope.

I just give up sleep. I’ve noticed by now that maybe my moods get a little crazier with sleep deprivation. Never mind. The deprivation unleashes a chemical reaction that feeds on itself, so that the less I sleep at night, the less I can sleep the next night, and the next. Night and day reverse themselves—but I’m not going to sleep during the day either. My body clock is no longer keeping time.

I don’t care. The future is unfurling ahead of me. I’m going to be a writer if it kills me. I will kill myself trying, I will get there, I’ve got to learn it, train for it, write it until the writing is perfect, until I get it, until I make it, I’m going to be real. This time I won’t fuck it up. I won’t fail.

The sun crests the horizon halfway, a winter sun, a blinding white. I stagger from the study lounge, carrying my piles of papers and books, and stumble down the stairs and into my room. My roommate is still asleep, the room still in shadow. As she mumbles in her sleep, I pull on my running shoes, go out into the cold, head across campus to the classroom building with the half-mile-long hall.

I run. Time stops. Thoughts stop. The never-ending pounding of my blood, the energy that surges through me all the time these days, it never runs out, I feel as if I will explode with it, I run. Up and down the long hall, compulsively touching the cold metal door on each end, must touch it or it doesn’t count, one mile, five miles, ten miles, chanting thinner, thinner, thinner, I am killing myself with the running, the starving, but I am alive, I run in the morning, between classes, during lunch, after school, during dinner, after workshops, before bed, and when I stop, I panic, afraid that until I run again, the flesh will creep back on my body. I’ve got to burn it off, get down to bones, a running, writing, starving skeleton, I eat only carrots and mustard, drink gallons of coffee, chatter with my friends, who tell me to stop, who worry, but they don’t understand, the flesh is always encroaching, trying to drown me, I will be thin, clean bones.

Minneapolis

1990

I am caught. I pace up and down the hospital halls, the eating disorders ward back home, refusing to believe I’m half dead. These doctors are fools, my parents’ terror unfounded. Let me out! I holler. Leave me alone! I scream as the nurses chase me with Dixie cups of Ensure, the evil drink, all calories and fat. They’re trying to make up for what I’m burning while pacing, pacing, pacing the halls, panicked, hyper, locked in. I beat on the doors, crying, yell at my parents, stare at the food they put in front of me six times a day, Get it away, I won’t eat it, you can’t make me.

The doctor tells my parents I’m depressed. I know I’m not. Something else entirely is wrong. But doctors always say people with eating disorders are depressed. His diagnosis ignores my agitation, the fact that I sail up and crash down minute by minute. I guess he has his reasons: the extremity of my anorexia and bulimia is, to say the least, distracting. I have a life-threatening condition. No one—not my parents, not the therapists, and certainly not the doctors—has time to focus on the mayhem of my moods. Their primary goal is keeping me alive. But they’re missing the forest for the trees. (That happens to this day to patients with eating disorders. Doctors zoom in on the havoc that starving, bingeing, and purging wreaks on the body; and while it’s certainly true that some people with eating disorders have depression, the doctors assume that all of them do. So in people with eating disorders but without depression, the symptom is treated, but not the cause, and the physicians end up ignoring the mood disorders that the patients may actually have. The real underlying mental illness runs wild, advancing steadily, irreparably damaging the mind.)

Fuck this! I shout at my parents. I stand up from my chair and say again, Fuck this!

Marya, sit down.

No! I shout. I pace in circles around the room. The other patients and their families watch me from the corners of their eyes. My brain is burning. I stand over my parents, waving my arms. You can’t just keep me here! I scream. What about my civil rights?

You have no civil rights, my mother points out. Not until you’re eighteen.

I’m moving to California, I say.

What are you talking about?

I’ll live with Anne (she’s my father’s first wife), and I’ll go to school and everything.

They stare at me.

It will be totally good for me, I say, honing my argument—this plan has just occurred to me in the last three minutes, but now it is essential, imperative, that I go. It is the most important thing ever in my whole life.

I perk up, suddenly loving and cheerful. It will be totally healing for me, I say. I will totally get better. You won’t have to worry about me. I’ll totally take in the sea air. It’s very centering out there.

California will be perfect. No one will watch me.

I’ll totally take long walks on the beach, I say. I’ll walk in the sunshine and celebrate the rain. I’ll get back in my body. I’ll do yoga. I’ll totally blossom. You see? It’s perfect. It’s just the thing.

My parents look at each other.

A few weeks later, they let me out of lockup, and I’m sitting on a plane.

California

1990

Here I am, healing. Centering. By now I’m convinced that my eating disorder is entirely sensible, necessary, that I’m completely sane and everybody else is nuts. Obviously I had to get out of there.

I rattle through the salt-air night in the back of a pickup truck, heading for Bodega Bay. The bottles of booze, the baggies of pot, the friends from school. We trudge through the dunes, lie on our backs, stare up at the ocean of sky. I am in heaven. This is my hideaway. Here, I can starve without anyone stopping me. I can drink myself high, smoke myself into a steady drifting down. Here, I can write all night. If I can just make it through high school, I can escape to college in some city far away. I’ll be a writer and show them all that I am not a fuckup, I can make it, I am real.

The moods are steady, sky-high. My mind is racing ahead and I chase it, writing as fast as I can, failing heart stuttering, body disappearing. I can do anything. Nothing can stop me.

I’m a flurry of motion, sitting on the floor of my bedroom, arms flying, shuffling papers into piles, brain racing, reading snippets of writing, hopping up to get something on my desk, making rapid little red-pen marks on the pages, cutting and pasting, short of breath, pulse pounding, I am back in my element, where I can do a thousand things at once, fueled by the rabid energy triggered by the booze, no food, no sleep, I stand up and compulsively do three hundred leg lifts, balancing on the back of the chair—and I leap onto the chair and pierce my nose with a safety pin—and I climb out my window onto the roof, flinging my head back to look at the glorious blanket of stars and their halo, and the round-bellied moon—and I spin around in circles, arms out, teetering near the edge, dizzily gazing out over the dark, thick woods that surround the house—and I hop back in the window, grab my jacket, and dash down the stairs and out the door.

I walk down the long driveway onto the winding dark road that runs nearby, the Spanish moss hanging in heavy swags from the cypress and eucalyptus trees. I walk down to the strip mall in town, the neon signs fizzling in the night. I am violently alive. Every snap and spit of the neon pierces my eyes. A few cars go by, the whoosh of their tires making a hollow echo in my ears. This is my secret life, these nights I prowl and hide in shadows in the dark, walk the roads near their guardrails, the hills dropping sharply from the road to the valley below. Eventually, the lights, the noise, become too much, and the frenzied intensity begins to fray, tearing at my brain, slicing through my body like razor blades, and I walk down the road to my boyfriend’s house. He is older, stupid, stoned, and he passes me the joint and I take a deep drag and pass it to his sister and get up to get myself a drink. I flop belly-down on the carpet, watch the interior of my mind as it empties of thoughts. The agitation begins to subside, and I slide into a rocking, gentle nothingness. We watch idiotic reruns on TV. I am starving, and the hunger pinches at my gut. My head lolls. I lay face down on the carpet, the laugh track on the television rolling over me. I fall asleep.