Полная версия

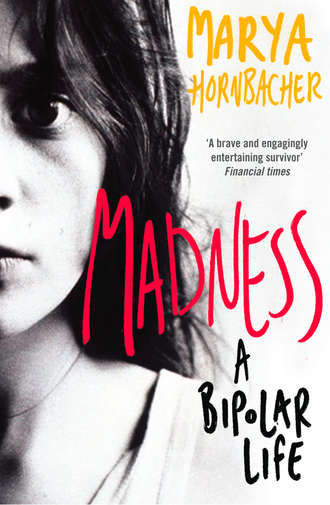

Madness: A Bipolar Life

Back in bed, she wraps me tight in my quilt, my arms and legs and feet and hands all covered, kept in so they won’t fly off. The goatman has gone away for the night. She sits on the edge of my bed, smoothing my hair. I am wrapped up like a package. I am a caterpillar in my cocoon. I am an egg.

She stays with me until, near dawn, I fall asleep.

What They Know

1979

They know I am different. They say that I live in my head. They are just being kind. I’m crazy. The other kids say it, twirl their fingers next to their heads, Cuckoo! Cuckoo! they say, and I laugh with them, and roll my eyes to imitate a crazy person, and fling my arms and legs around to show them that I get the joke, I’m in on it, I’m not really crazy at all. They do it after one of my outbursts at school or in daycare, when I’ve been running around like a maniac, laughing like crazy, or while I get lost in my words, my mouth running off ahead of me, spilling the wild, lit-up stories that race through my head, or when I burst out in raging fits that end with me sobbing hysterically and beating my fists on my head or my desk or my knees. Then I look up suddenly, and everyone’s staring. And I brighten up, laugh my happiest laugh, to show them I was just kidding, I’m really not like that, and everyone laughs along.

I AM LYING on the bed. I am listening to my parents scream at each other in the other room. That’s what they do. They scream or throw things or both. You son of a bitch! [crash]. You’re trying to ruin my life! [crash, shatter, crash]. When they are not screaming, we are all cozy and happy and laughing, the little bear family, we love each other, we have the all-a-buddy hug. It’s hard to tell which is going to come next. Between the screaming and the crazies, it is very loud in my head.

And so I am feeling numb. It’s a curious feeling, and I get it all the time. My attention to the world around me disappears, and something starts to hum inside my head. Far off, voices try to bump up against me, but I repel them. My ears fill up with water and I focus on the humming in my head.

I am inside my skull. It is a little cave, and I curl up inside it. Below it, my body hovers, unattached. I have that feeling of falling, and I imagine my soul is being pulled upward, and I close my eyes and let go.

My feet are flying. I hate it when my feet are flying. I sit up and grab them with both hands. It’s dark, and I stare at the little line of light that sneaks in under the door.

The light begins to move. It begins to pulse and blur. I try to make it stop. I scowl and stare at it. My heart beats faster. I am frozen in my bed, gripping my feet. The light has crawled across the floor. It’s headed for the bed. I want it to hold still, so I press my brain against it, expecting it to stop, but it doesn’t. The line crosses the purple carpet. I want to scream. I open my mouth and hear myself say something, but I don’t know what it is or who said it. The little man in my mind said it, I decide, suddenly aware that there is a little man in my mind.

The line is crawling up the side of the bed. I tell it to go away. Holding my feet, I scootch back toward the wall. My brain is feeling the pressure. I let go of my feet and cover my ears, pressing in to calm my mind. The line crests the edge of the bed and starts across the flowered quilt. I throw myself off the bed. I watch the line turn toward me, slide off the bed, follow me into the corner of my room.

I want to go under the bed but I know it will follow me. I jump up on the bed, jump down, run into the closet and out again, the humming in my head is excruciatingly loud. The light is going to hurt me. I can’t escape it. It catches up with me, wraps around me, grips my body. I am paralyzed, I can’t scream. So I close my eyes and feel it come up my spine and creep into my brain. I watch it explode like the sun.

I drift off into my head. I have visions of the goatman, with his horrible hooves. He comes to kill me every night. They say it is a nightmare. But he is real. When he comes, I feel his fur.

I don’t come out of my room for days. I tell them I’m sick, and pull the blinds against the light. Even the glow of the moon is too piercing. The world outside presses in at the walls, trying to reach me, trying to eat me alive. I must stay here in bed, in the hollow of my sheets, trying to block the racing, maniac thoughts.

I turn over and burrow into the bed headfirst.

I HAVE THESE crazy spells sometimes. Often. More and more. But I never tell. I laugh and pretend I am a real girl, not a fake one, a figment of my own imagination, a mistake. I never let on, or they will know that I am crazy for sure, and they will send me away.

This being the 1970s, the idea of a child with bipolar is unheard of, and it’s still controversial today. No psychiatrist would have diagnosed it then—they didn’t know it was possible. And so children with bipolar were seen as wild, troubled, out of control—but not in the grips of a serious illness.

My father is having one of his rages. He screams and sobs, lurching after me, trying to grab me and pick me up, keep me from going away with my mother, but I make myself small and hide behind her legs. We are trying to leave for my grandmother’s house. We are taking a train. I have a small plaid suitcase. I come around and stand suspended between my parents, looking back and forth at each one. My mother is calm and mean. The calmer she gets, the more I know she is angry and hates him. She hisses, Jay, for Christ’s sake, stop it. Stop it. You’re crazy, stop screaming, calm down, we’re leaving, you can’t stop us. My father is out of control, yelling, coming at my mother, grabbing at her clothes as she tries to move away from him. Don’t leave me, he cries out as if he’s being tortured, choking on his words, don’t leave me, I can’t live without you, you are the reason I even bother to stay alive, without you I’m nothing. His face is twisted and red and wet from tears. He throws himself on the floor and curls up and cries and screams. I go over to him and pat him on the head. He grabs me and clutches me in his arms and I get scared and try to push away from him but I’m not strong enough. I finally get free and he stands up again, and I stand between them, my head at hip level, trying to push them apart. He kneels and grabs my arms, Baby, I love you, do you love me? Say you love me—and I pat his wet cheeks and say I love him, wanting to get away from him and his rages and black sadness and his lying-on-the-couch-crying days when I get home from preschool, and his sucking need, and I close my eyes and scream at the top of my lungs and tell them both to stop it.

My father calms down and takes us to the train station, but halfway there he starts up again and we nearly crash the car. We leave him standing on the platform, sobbing.

“Why does he get like that?” I ask my mother. I sit in the window seat swinging my legs, watching the trees go by, listening to the clatter of the wheels. I look at my mother. She stares straight ahead.

“I don’t know,” she says. I picture my father back at home, walking through the empty house to the couch, lying down on his side, staring out the window like he does some afternoons, even though I tell him over and over I love him. Over and over, I tell him I love him and that everything will be okay. He never believes me. I can never make him well.

CRAZY IS NOTHING out of the ordinary in my family. It’s what we are, part of the family identity, sort of a running joke—the crazy things somebody did, the great-grandfather who took off with the circus from time to time, the uncle who painted the horse, Uncle Frank in general, my father, me. In the 1970s, psychiatry knows very little about bipolar disorder. It wasn’t even called that until the 1980s, and the term didn’t catch on for another several years. Most people with bipolar were misdiagnosed with schizophrenia in the 1970s (in the 1990s, most bipolar people were misdiagnosed with unipolar depression). We didn’t talk about “mental illness.” The adults knew Uncle Joe had manic depression, but they didn’t mind or worry about it—just one more funny thing about us all, a little bit of crazy, fodder for a good story.

This is my favorite one: Uncle Joe used to spend a fair amount of time in the loony bin. My family wasn’t bothered by his regular trips to and from “the facility”—they’d shrug and say, There goes Joe, and they’d put him in the car and take him in. One day Uncle Frank (who everybody knows is crazy—my cousins and I hide from him under the bed at Christmas) was driving Uncle Joe to the crazy place. When they got there, Joe asked Frank to drop him off at the door while Frank went and parked the car. Frank didn’t think much of it, and dropped him off.

Joe went inside, smiled at the nurse, and said, “Hi. I’m Frank Hornbacher. I’m here to drop off Joe. He likes to park the car, so I let him do that. He’ll be right in.” The nurse nodded knowingly. The real Frank walked in. The nurse took his arm and guided him away, murmuring the way nurses always do, while Frank hollered in protest, insisting that he was Frank, not Joe. Joe, quite pleased with himself, gave Frank a wave and left.

Depression

1981

Maybe it begins when I am seven. I’m in bed. It’s too sunny outside, I can’t go out. The blinds are drawn and yet they let in a little light, and the little light pierces my eyes. I turn my face into my pillow. It’s cool and safe in my sheets. My father comes in.

Time to get up, kiddo.

(Silence.)

Kiddo.

(I pull the pillow over my head to block the incessant light.)

Kiddo, are you getting up?

No.

Why not?

I’m skipping today.

What’s the matter with today?

I sigh. I despair of ever getting up again. I cannot move. I will not move. Everything is horrible. I want to go to sleep forever.

I can’t go to school, I say.

Why not?

I bang my head on the mattress and let out a shriek. I sigh and flop onto my back and shade my eyes.

There’s an art project. I burst into tears.

Oh, my father says, unsurprised. Is it complicated?

It’s very complicated, I wail. I can’t do it. I don’t want to do it. So I’m sick. I wipe my nose and let the tears fall into my ears.

Okay, my father says.

I’m staying home.

Okay.

Okay. Okay. Now I will be okay. No crowded classroom, no scissors, no paste, no other kids, no cafeteria lunch, no recess, no wide sky and too much sun.

The world outside swells and presses in at the walls, trying to reach me, trying to eat me alive. I must stay here in the pocket of my sheets, with my blanket and my book. I will not face the world, with its lights and noise, its confusion, the way I lose myself in its crowds. The way I disappear. I am the invisible girl. I am make-believe. I am not really there.

I don’t come out of my room for days. Days bleed into weeks. I lie in bed in the dark.

Prayer

1983

On my knees. Praying. Pleading. The basement floor is cold beneath my knees. I come here to hide, to hide my prayers. My mother would mock me. God is merely a weakness for people who need to believe. She wouldn’t understand that I am chosen to speak for all the sorrows of the world.

I’m not crazy. God has called me and I have no choice but to answer, or I will be sent to hell. It all depends on me. And so I pray myself to sleep, and pray the second I wake, and pray all day, terrified that God will catch me slacking off and punish me severely.

My knees grow sore and my heart beats a million miles an hour. I panic. I practically pant. My mind spins with the things I am forgetting to pray for, things I have done, there is a light flashing in my brain, like the headlight of a train in the dark, the dark is my mind, which teems with sins, which torment me with their noise. I can hear the sins whisper; are they inside my head or outside my ears? Are they in the basement? Coming from the water heater, the washing machine? God answers at last. You may get up, I hear him say. His voice reverberates against the concrete walls.

Halfway up the stairs, I hear God call me to prayer again. I kneel and pray. He calls me in the kitchen. Calls me in my bedroom. Calls me at school. I raise my hand, hurry into the restroom, kneel on the floor of the stall, the restroom empty and echoing with my rapid breath, echoing with the shrieking, pounding in my head. I pray in class. I pray in the car, after dinner, all night long—hours after silence has settled around the house, my mouth moves with manic prayers.

God watches me, sees my every mistake, every sin. God’s voice booms in my head, now praising me, his chosen one, now spitting at me, sending the snake into my mind. It curls itself around itself, its body pressed against the walls of my skull. I lie in bed, rocking, my head in my hands, the snake flicking its tongue at the backs of my eyeballs. It sinks its teeth into the gray, wet brain. I press my open mouth to the mattress and scream.

Food

1984

God has left. My mind is spinning. I’m out of control, unable to contain myself. I am propelled forward, toward something drastic. I’m going to hurl myself into anything that will stop the thoughts. Suddenly I find a focus. It’s incredibly intense. I must, I must fill myself to bursting, then rid myself of that fullness. Food. It’s all about food.

My body disgusts me. I stand naked in my bedroom in front of the mirror. I pinch the flesh, the needy, hungry, horrible flesh, the softness that buries the perfect clean bones. I pinch hard; red welts appear on my skin. The body revolts me, its tricks, its betrayals, its lies. I starve and starve, and then it happens—the black hole in my chest yawns open, and suddenly I’m in the kitchen, standing at the counter, stuffing food into my mouth, anything I can find, anything that will fill me up. Food covers my face, my cheeks bulge with it, but I still can’t stop, my hands move back and forth from food to mouth. I hate myself for it. I want to be thin, I want to be bones, I want to eliminate hunger, softness, need.

Every day I come home from fourth grade and try to avoid the kitchen. I sit in my bedroom, clutching the seat of my chair. The empty house echoes its silence around me. I sit, gritting my teeth, and then the hum of compulsion drives me into the kitchen. I eat. Leftovers, frozen dinners, whatever I can stuff in my mouth.

I lean over the toilet with my fingers down my throat. I throw up, body heaving, until I’m spitting up blood. I straighten up. I am empty. Clean. I run my hands over the flat of my stomach, play the xylophone of my ribs. Satisfied, absolved, I open the door, walk calmly down the hall to the kitchen, and do it again.

It’s my secret and my savior. It’s reliable. It saves me from the unpredictable mind, where the thoughts are a cesspool, swirling, eddying with rip tide. When I starve, the sinking, pressing black sadness lifts off me, and I feel weightless, empty, light. No racing thoughts, no need to move, move, move, no reason to hide in the dark. When I throw up, I purge all the fears, the paranoia, the thoughts. The eating disorder gives me comfort. I couldn’t let it go if I tried.

It is what I need so badly, a homemade replacement for what a psychiatrist would prescribe for me if he knew: a mood stabilizer. My eating disorder is the first thing I’ve found that works. It becomes indispensable as soon as it begins. I am calm in starvation, all my apprehensions focused. No need to control my mind—I control my body, so my moods level out. I live in single-minded pursuit of something very specific: thinness, death. I act with intention, discipline. I am free.

My parents wonder where all the food is going. I say I’m a growing girl.

The Booze under the Stove

1985

Nothing is going fast enough. At school, the teachers are talking as if their mouths are full of molasses. Their limbs move in slow motion. Pointing to call on someone, the teacher lifts her arm as if it is filled with wet sand. I swear to God I think I am going insane, it is so slow, while my thoughts whistle past like the wind, so fast I can barely keep up. I turn my mind inward to watch them. They move in electric currents, crackling, spitting, sending out red sparks.

The other students are slow, stupid, asleep. In the hallways, they move like a herd of slugs, wet and shapeless, inching toward the door. I explode out of school, dancing as fast as I can across the playground, whipping in circles around the tetherball pole, dashing off across the yard, trying to shake off this incredible energy, this amazing energy. I’m ten years old and I might as well be on speed.

My parents are on their way out the door. Eat dinner! they call, but I am too fast for them, their voices recede in the distance as I race through the house, bouncing off the walls. I’ve been pleading with them to let me stay home by myself, and so they do, heading off to their meetings or dinners or places unknown. Maybe not a great idea to let a ten-year-old stay home alone, but I’ve twisted their arms, and they’re immersed in work and in their own nightmare marriage, avoiding each other, avoiding the fights, thinking up reasons to be gone. They work compulsively, and when they’re not working they see friends, putting on the face of the happy couple. Everything’s fine. We’re the perfect little family. People tell us that all the time.

And I am home alone with a raw steak on the counter, hopping up and down, my mind jetting about. Time for homework! I reach into my bag and throw my books and papers up in the air, ha ha! Watch this, ladies and gentlemen, the amazing Marya! Look at her go! Can you believe the incredible speed? My homework covers the kitchen floor, and I crawl around picking it up, talking to myself: Hip-hop, my friends, never liked rabbits, must get a tiger, it will sleep in my bed, take it for walks, I need new shoes, fabulous shoes, I will show all of them, hark the herald angels sing! Christmas is smashing! Love it, people, just love it—I hop up, slap my hand to my chest, salute the refrigerator, click my heels, make a sharp turn, and walk stiffly over to the kitchen table, where I whip through the papers, laying them out perfectly in a complex system, the most efficient system, each corner of each page touching the corner, exactly, of the next. Having arranged the papers, I gallop up and down the hallway, slide into the kitchen as if I’m sliding into third, yank open the refrigerator, pull out some mushrooms, chop them up, my knife a blur, toss them into the frying pan, sauté them—but they need a little something. A little zing. I pull open the cupboard beneath the sink, pull out the brandy, splash it in the pan. But now that I think of it, what are all those bottles?

I turn off the burner, bouncing up and down, and open the cupboard again.

Booze.

I pull out a jug of Gallo, stagger underneath its weight. A little wine with dinner, the very thing, don’t you think? I pour it into a giant plastic Minnesota Twins cup and collapse with my mushrooms and tankard of wine at the dining room table.

I get absolutely shitfaced. I am shitfaced and hyper and ten years old. I am having the time of my life.

I lope up and down the hallway, singing Simon and Garfunkel songs, juggling oranges. I do my homework in a flurry of brilliance, total efficiency, the electric grid of my mind snapping and flashing with light. I am in the zone, the perfect balance between manic and drunk, I am mellow, I’m cool, cool as cats. I’ve found the answer, the thing that takes the edge off, smoothes out the madness, sends me sailing, lifts me up and lets me fly.

It’s alchemy, the booze and my brain, another homemade mood stabilizer, and it stabilizes me in a heavenly mood. I am in love with the world, gregarious, full of joy and generosity toward my fellow man. My thoughts fly, but not up and down—they soar forward in a thrilling flight of ideas, heightened sensations, a creative rush, each thought tumbling into the next. It’s even more perfect than eating and throwing up.

My future with alcohol is long and disastrous. But at first, it works wonders for me. No longer low, not yet too high. Just on a roll, energetic, inspired. I truly believe the booze is helping. I’ll believe this, despite all evidence, for years.

Eventually I stagger into bed and, for once, fall asleep.

Meltdown

1988

My moods start to swing up and down almost minute to minute. I take uppers to get even higher and downers to bring myself down. Cocaine, white crosses, Valium, Percocet—I get them from the boys who skulk around the suburban malls hunting jailbait. I’m an easy target, in the market for their drugs and willing to do what they want to get them for free. The boys themselves are a high. They have something I want. They are to be used and discarded. The trick is to catch them and make them want the girl I am pretending to be. Then twist them up with wanting me, watch them squirm like worms on a hook, and throw them away.

I find myself on piles of pillows in their basements, pressed down under their bodies, their lurching breath in my ear. They are heavy, damp, hurried, young, still mostly dressed. I don’t know how I’ve wound up here, and I want it to end, and I repeat to the rhythm of their bodies, You’re a slut, you’re a whore, and I want a bath, want to scrub them off, why does this keep happening? Why don’t I ever say no? There’s a rush when they want me, and they always do, they’re boys, that’s what they want, and once they’ve got me half lying on the couch, each basement, each boy, each time, my brain shuts off, the rush is over, I’m numb, I want to go home. The impulsive tumble into the corner, the racing pressure in my head always ends like this: I hate them, and I hate myself, and I swear I won’t do it again. But I do. And I do. And I do.

And then I am home in my bedroom, blue-flowered wallpaper and stuffed animals on the bed, stashing my baggies of powders and pills. If I hit the perfect balance of drugs, I can trigger the energy that keeps me up all night writing and lets me stay marginally afloat in junior high, accentuating the persona I’ve created as a wild child, a melodramatic rebel—black eyeliner and dyed black hair, torn clothes, a clown and a delinquent, sulking, talking back. In class, I fool everyone into thinking I’m real.

But then I come home after school to the empty, hollow house, wrap into a ball in the corner of the couch, a horrible, clutching, sinking feeling in my chest. Nothing matters, and nothing will ever be all right again. I go into rages at the slightest thing, pitching things around the house, running away in the middle of the night, my feet crunching across the frozen lake. I cling to the cold chainlink fence of the bridge across the freeway and watch the late-night cars flash by, my breath billowing out into the dark in white gusts.

DAY YAWNS OPEN like a cavern in my chest. I lie in the dimness of my room, the blinds shut tight and blankets draped over them. I weigh a million pounds. I can feel my body, its heavy bones, its excess flesh, pressing into the mattress. I’m certain that it sags beneath me, nearly touching the floor. My father bangs on the door again. Breakfast! he calls.