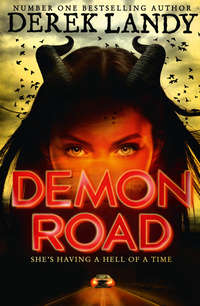

Полная версия

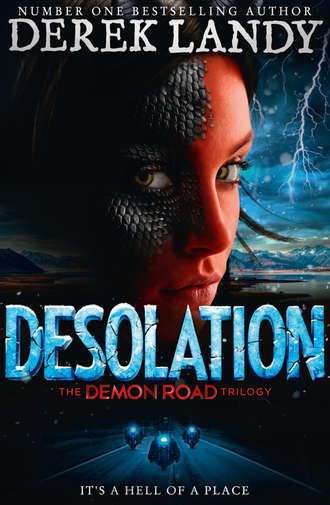

Desolation

“Yeah,” Amber said. Then she swung round, walked back to the Hounds. “You know what?” she said. “You’re a bunch of jerks. Standing there all silent. You think you’re intimidating? You don’t intimidate me. Everyone is sooooo scared of you – but we stayed ahead of you without a problem. The only reason you’re this close to us is because we stopped and waited for you to catch up. And you still can’t get me. So screw you, dickbrains. Go have sex with your motorcycles, and when you’re finished with that go tell your boss that he can kiss my fine red ass.”

She tried to give them the finger, but ended up waving her bandaged hand at them instead. Hissing, she spun on her heel and marched back to Milo.

“Yep,” Milo muttered. “Handled that very well.”

She reverted, painfully, and they drove back into town without doing a whole lot of speaking. They parked in the motel lot beside a police cruiser and were heading inside when a uniformed man walked out, met them halfway.

“Mr Sebastian,” he said. “Miss Lamont, good afternoon. Welcome to Desolation Hill.”

He was in his forties, with dark hair and heavy-lidded eyes. He had a long, lined face, not entirely unattractive. His badge was gleaming on his black uniform beneath his open jacket, and his gun was holstered.

“Thank you,” said Milo.

“My name is Trevor Novak. I’m the Chief of Police here.”

“It’s a very nice town,” said Amber.

“It can be,” said Novak. “Although it has a habit of attracting the wrong kind of visitor.”

“Is that so?” said Milo.

“Regrettably. Especially at this time of year.” Novak looked at them both before continuing. “You have been told, I understand, about our festival. Naturally, you’re curious. I appreciate curiosity – it’s what has me here talking to you, after all. And, while I’m not about to satisfy that curiosity, hopefully I can explain our attitude to you. We’re a quiet town, or at least we want to be, and we value our traditions. This festival just happens to be our most cherished, most valued tradition.”

“What does it celebrate?” Milo asked.

“Our history,” said Novak. “Our culture. Our heritage. And our success. Many other towns, a lot like ours, dried up and were blown away after the gold rush. But Desolation Hill remained standing. Even more towns dried up and were blown away during the various recessions and depressions … but Desolation Hill has stayed strong. I put this down to the people. We have the single lowest crime rate, per capita, in America.”

Milo nodded. “Certainly something to be proud of.”

“It is, Mr Sebastian, yes. And I am proud.”

“We’re not planning on committing any crimes, if that’s what you’re worried about,” Amber said, offering up a smile.

“I’m not suggesting you were,” said Novak, not offering one in return. “I only wish to impress upon you the need to obey our rules. The festival is for townsfolk only. When you check out of the Dowall Motel on Wednesday morning, you will receive a police escort to the edge of town.”

“Uh …”

“It’s nothing personal,” Novak said. “I trust you won’t be offended.”

“Not offended,” said Milo. “But a police escort does seem a little extreme.”

“We take our rules very seriously. I’m sure you have questions, I’m sure you have many, but please understand that to ask these questions of the townsfolk could lead to a certain degree of irritation. We have traditions we would prefer to keep private, and questions we would prefer not to answer. I’m sure you and your … niece appreciate this desire.”

Milo took a moment. “Sure,” he said.

“I can, of course, see the family resemblance immediately,” said Novak. “Some of my officers, I’m afraid to say, are not so attentive to detail. They may have questions for you.”

“I’m sure there’s no need to bother them,” Milo said.

Novak nodded. “That’s what I was thinking. We like to mind our own business here. I trust you will do the same.”

“Naturally,” said Milo.

“Of course,” said Amber.

Novak adjusted his gun belt, and nodded to them. “Very nice to meet you, and welcome to Desolation Hill.”

“Thanks,” said Milo.

Novak walked to his car, went to get in, but paused. “One of my officers alerted me to some bikers on the edge of town,” he said. “They have anything to do with you?”

“No, sir.”

“Well, okay then. Have a nice day.” He nodded again, got in his car, and they watched him drive away.

“So what do you think of the place?” Milo asked.

“I haven’t decided,” said Amber. “People here are weird. They’re downright rude to me and they’re overly polite with each other. That Novak guy is a little creepy, and I don’t have a clue what this festival is about, but already it’s annoying the crap out of me. Plus, every second that goes by I just want to shift. It’s actually uncomfortable to stay normal.”

“It’s worth it, though,” said Milo.

“Yeah,” she said, a little grudgingly. “I really like this whole barrier thing they’ve got going on. What are we going to do on Wednesday? We can’t leave town – the Hounds will be on us the moment we try.”

“I thought they didn’t intimidate you.”

“Are you nuts? Of course they do. I just said that because they were freaking me out.”

“We’re not leaving,” said Milo. “We can’t be escorted out, either – that’d be like delivering ourselves straight to them. We’ll check out early, find an out-of-the-way place to park that’s still within the town limits, and camp out till Saturday. We keep our heads down, ignore anything to do with their festival, and we’ll be fine.”

“And in the meantime,” said Amber, “we find out who put up that barrier. It’s got to be someone like us, right? Someone hiding from a demon?”

“Maybe.”

“If we can talk to whoever’s behind it, maybe we can make a barrier of our own. You’d be able to do something like that, wouldn’t you?”

Milo frowned. “Me? I know nothing about this kind of thing.”

“Well, yeah, but you know the basics.”

“What basics, Amber? I know the lore. I know some of the traditions. I don’t know how to do anything. Buxton knows, not me, and he’s too busy setting up a new life for himself to come up here and give us advice.”

“Well … maybe we won’t need him. Maybe whoever put up the barrier will show us what we have to do.”

“I guess it’s possible.”

She gave him a disapproving frown. “You don’t sound convinced.”

“I hate to break it to you, Amber, but neither do you.”

AUSTIN COOKE RAN.

He ran from his house on Brookfield Road all the way past the school, past the corner store that was always closed on Sundays, and up towards the fire station, where they kept the single engine that had never, in Austin’s memory, been used for any fire-based emergencies. The volunteer fire fighters brought it out every once in a while and parked it at the top of Beacon Way, the only pedestrian street in Desolation Hill, and they held pancake breakfasts for fund-raising and such, but they’d never had to put out any actual fires – at least not to Austin’s knowledge.

Once the picture of the smiling Dalmatian on the fire-station door came into view, Austin veered left, taking the narrow alley behind the church. His feet splashed in puddles. His sneakers, brand new for his twelfth birthday, got wet and dirty and he didn’t care.

With his breath coming in huge, whooping gulps and a stitch in his side sliding in like a serrated knife, Austin burst from the alley on to the sidewalk on Main Street and turned right, dodging an old lady and sprinting for the square. A beat-up old van trundled by. Up ahead he could hear laughter. A lot of laughter.

Three of them – Cole Blancard, Marco Mabb and Jamie Hillock. Mabb was the biggest and Hillock had the nastiest laugh, but Cole Blancard was the worst. Cole dealt out his punishments with a seriousness that set him apart from the others. Where their faces would twist with sadistic amusement, his would go strangely blank, like he was an impartial observer to whatever degrading activity he was spearheading. His eyes frightened Austin most of all, though. They were dull eyes. Intelligent, in their way, but dull. Cole had a shark’s eyes.

Austin waited for a car to pass, then ran across the street, on to the square. They heard him coming, and turned. Hillock laughed and punched Mabb in the arm and Mabb laughed and returned the favour. Cole didn’t laugh. He only smiled, his tongue caught between his teeth. He had a large handful of paper slips.

Austin staggered to a halt. He didn’t dare get any closer. He’d run all this way to stop them, even though he knew there was nothing he could do once he got here.

The ballot box was old and wooden. It had a slot an inch wide. Cole Blancard turned away from Austin and stuffed all those paper slips through that slot, and Austin felt a new and unfamiliar terror rising within him. Panic scratched at his thoughts with sharp fingers and squeezed his heart with cold hands. Mabb and Hillock took fistfuls of paper slips from their pockets, gave them over, and Cole jammed them in, too.

A few slips fell and the breeze played with them, brought them all the way to the scaffolding outside the Municipal Building. The three older boys didn’t seem to mind. When they were done, they walked towards Austin, forcing him to move out of their way. Mabb and Hillock sniggered as they passed, but Cole stopped so close that Austin could see every detail of the purple birthmark that stretched from Cole’s collar to his jaw.

“Counting, counting, one, two, three,” Cole said, and rammed his shoulder into Austin’s.

Austin stood there while they walked off, their laughter turning the afternoon ugly. One of those slips scuttled across the ground and Austin stepped on it, pinned it in place.

He reached down, picked it up, turned it over and read his own name.

THE VAN WAS OLD and rattled and rolled, coughed and spluttered like it was about to give up and lie down and play dead, but of course it defied expectations, like it always did, and it got them to Desolation Hill with its oil-leaking mechanical heart still beating. That was close to a 4,000-mile journey. Kelly had to admit she was impressed. She thought they’d have to abandon the charming heap of junk somewhere around Wyoming, and pool what little money they had to buy something equally cheap but far less charming to take them the rest of the way.

“I think you owe someone an apology,” Warrick said smugly.

Kelly sighed. “Sorry, van,” she said. “Next time I’ll have more faith in your awesome ability to keep going. There were times, it is true, when I doubted this ability. Uphill, especially. Even, to be honest, sometimes downhill. You have proven me wrong.”

“Now swear everlasting allegiance.”

“I’m not doing that.”

“Ronnie,” Warrick called, “she won’t swear everlasting allegiance to the van.”

“Kelly,” said Ronnie from behind the wheel, “you promised.”

“I promised when I didn’t think the van would make it,” said Kelly. “Promises don’t count when you don’t think you’ll ever have to keep them.”

“I’m not sure that’s technically correct,” said Linda, still curled up in her sleeping bag.

“Hush, you,” said Kelly. “You’re still asleep.”

“Big Brain agrees with me,” said Warrick. “You tell her, Linda!”

“Two,” Kelly commanded, “sit on Linda’s head, there’s a good boy.”

Two just gazed at her, his tongue hanging out, and wagged his tail happily.

“Swear allegiance to the almighty van,” said Warrick.

“Not gonna happen.”

“Then swear allegiance to this troll,” he said, pulling an orange-haired little troll doll from his pocket and thrusting it towards her. “Look, he’s got the same colour hair as you.”

She frowned. “My hair is red. That’s orange.”

“It’s all the same.”

“It’s really not.”

“Swear. Allegiance. To our Troll Overlord.”

“Warrick, I swear to God, stop waving that thing in my face.”

He kept doing it and she sighed again, and crawled over the seat in front to sit beside Ronnie. “Pretty town,” she said.

Ronnie opened his mouth to reply, but hesitated.

She grinned. “You were going to say it, weren’t you?”

“No, I wasn’t.”

“You so were,” came Linda’s muffled voice. Then, “Two, get off me.”

Kelly grinned wider. “You were going to say appearances can be deceiving, weren’t you?”

“Nope,” said Ronnie, shaking his head. “I was going to say something completely different. I was going to say, ‘Yes, Kelly, it does look like a nice town.’”

“But …?”

“Nothing. No buts. That was the end of that sentence.”

“Warrick,” said Kelly, “what do you think? Do you think Ronnie is fibbing?”

“I’m not talking to you because you have refused to swear allegiance to either my van or my troll doll,” said Warrick, “but, on a totally separate note, I think our Fearless Leader is totally telling fibs and he was, in fact, about to utter those immortal words.”

“You’re all delusional,” said Ronnie. “Now someone please tell me where I’m supposed to go in the whitest town I’ve ever been to. Seriously, there is such a thing as being too Caucasian.”

“Take this left coming up,” Linda said.

“She’s a witch!” cried Warrick.

“It’s GPS.”

“Not a witch, then,” Warrick said. “False alarm, everybody. Linda is not a witch, she just has an internet connection. You know who was a witch, though?”

“Stefanianna North was not a witch,” Kelly said.

“You didn’t see her!” Warrick responded. “You don’t know!”

“Neither do you. You were unconscious the whole time.”

Warrick sniffed. “It wasn’t my fault I was drugged.”

“You weren’t drugged,” said Ronnie, “you were high. And that was your fault because it was your own weed you were smoking.”

“Aha,” said Warrick, leaning forward, “but why was I smoking it?”

“To get high.”

“No,” Warrick said triumphantly. “Well, yes, but also because of the socio-economic turmoil this world has been going through since before I was even born. My mother had anxiety issues when I was still in the womb, man. That affects a dude, forces him to seek out alternative methods of coping later in life.”

“So that’s what you were doing?” Kelly asked. “You were coping?”

“I was trying to,” Warrick said. “And that’s when Stefanianna came to kill me. I don’t remember much—”

“Because you were high.”

“—but I do remember her saying something like, ‘First I’ll kill you, then I’ll kill your friends.’ And I was all, like, hey, don’t you touch my friends, because I’m very protective of you guys, you know?”

Kelly nodded. “We bask in your protection.”

“But then Two woke up,” said Warrick, “and, as we all know, witches are terrified of dogs, especially pit bulls.”

“That’s not a thing,” said Linda.

“Well, maybe not particularly pit bulls, but we all know that witches are terrified of dogs, right?”

“That’s not a thing, either,” said Linda.

Warrick frowned. “So what are witches terrified of?”

“Fire,” said Ronnie.

“But then why did she run away? The moment she saw Two she screamed and ran.”

“That’s because Stefanianna is terrified of dogs,” Kelly said.

“Yes!” said Warrick. “Exactly! See?”

“But that doesn’t mean she’s a witch.”

“Why doesn’t it?”

“Because why would it?”

Warrick frowned again. “I don’t … I don’t see what you’re saying here.”

“Take a right, Ronnie,” Linda said. “Should be a hill up ahead.”

Ronnie took the right. “I see it. That where we’re going?”

“Yep.” Linda sat up. Her dark hair was a mess.

“How was your nap?” Kelly asked.

“Terrible,” Linda answered. “I feel like a hamster in a ball that’s been kicked down a hill for three hours. And Two kept farting.”

Two whined in protest.

“That wasn’t Two,” Warrick said meekly.

“Oh, you’re so gross,” Linda said, crawling forward. She left the cushioned rear of the van and joined Warrick on the long seat behind Kelly.

They got to the top of the hill and Kelly read the sign.

“The Dowall Motel,” she said, and frowned up at the building. “You know, for a pretty town, this is a creepy motel.”

“They better allow pets,” Warrick said.

“I don’t care,” said Linda. “All I want is a real bed tonight. I’m sick of sleeping in the van.”

“Swear allegiance,” Warrick whispered.

They parked, and got out, and Kelly immediately reached back in to grab her jacket. Two hopped out as well, started to hump a small tree, but Warrick shook his head.

“Sorry, buddy, you’re gonna have to stay in the van until we find out if they allow pets.”

“He doesn’t understand you, Warrick,” said Linda, rubbing her arms against the cold.

“Well, no, but he understands basic English, though.”

Linda looked at the dog. “Two. Stop having sex with the tree. Sit. Sit. Two, sit.” She raised her eyes to Warrick. “He’s not sitting.”

“You know he doesn’t like to be told what to do. It’s conversational English he responds to, not orders. We’re not living in Nazi Germany, Linda, okay? We have something here in America that I like to call freedom. Freedom to choose, freedom to worship, freedom to congregate in groups of like-minded individuals, freedom of the press and free speech and freedom to do other stuff … Land of the free, home of the brave. That’s where we live, that’s how we live, and that’s why Two won’t sit when you order him to sit.”

“Fine,” said Linda. “Then you tell him to do something.”

“I’m not gonna tell,” said Warrick. “I’m gonna ask.” He cleared his throat, and looked down at Two. “Hey, buddy,” he said, “mind leaving the tree alone and waiting in the van for a minute?”

Two barked, and jumped into the van.

Linda picked up her bag and slung it over her shoulder. “Coincidence.”

“Two’s a smart puppy dog.”

“Of course he jumped into the van. It’s freezing out here.”

“Come on, Linda,” Warrick said, shutting the van door. “Swear allegiance to the doggy.”

Kelly walked on ahead, into the motel, where the first thing that registered was a moose head on the wall behind the front desk.

The woman at the desk looked up. She was tall, skinny, with a mole beneath her right eye and a blouse buttoned all the way up to her throat. Dear God, she was wearing a brooch.

Kelly smiled. “Hi.”

The woman, whose nametag identified her as Belinda, frowned back at her. The others walked in, and Belinda’s eyes widened and she stepped back.

“You,” she said in a surprisingly husky voice. “We do not allow your kind in here.”

Ronnie and Linda froze.

“Me?” said Ronnie, a black man.

“Or me?” said Linda, a Chinese girl.

“Him,” said Belinda, pointing a trembling finger at Warrick.

“Me?” Warrick said. “What’d I do?”

“You’re a … you’re a beatnik,” Belinda said, the word exploding out of her mouth like a chunk of meat after a Heimlich.

“I am not!” said Warrick.

“We do not allow beatniks in this motel!”

“I’m not a beatnik! Stop calling me a beatnik!”

“Excuse me,” Kelly said, still smiling as she neared the desk, “but what seems to be the issue with beatniks?”

“My mother never approved,” Belinda said, practically livid with disgust. “She said never shall a beatnik sleep under this roof, and I say a beatnik never shall!”

Kelly nodded. “That’s very understandable. Beatniks are terrible people. Although Warrick isn’t actually a beatnik.”

“My mother said they will come in various guises.”

“Uh-huh. Yes, but the thing is Warrick isn’t one of them.”

“I hate jazz music,” said Warrick.

“He does,” said Kelly. “He hates jazz music.”

“He’s got a beatnik beard, though,” said Belinda.

Warrick frowned. “My soul patch? I just don’t like shaving under my lip. My skin is sensitive, man.”

“I assure you,” Ronnie said, giving Belinda a smile, “my friend isn’t a beatnik. He just shaves like one. He listens to regular music and I don’t think I’ve ever heard him talk about bettering his inner self.”

“I leave my inner self alone and it leaves me alone,” said Warrick. “We’re happier that way.”

Belinda hesitated.

“The moment he starts wearing berets and playing the bongos,” Kelly said, “we’ll kick him out ourselves.”

“Very well,” Belinda said dubiously. “In which case, welcome to the Dowall Motel. This is a family business. How may I help you?”

“We don’t have any reservations,” said Ronnie, “but we were wondering if you had any rooms available? Two twin rooms, ideally. We don’t mind bunking up.”

“How long will you be staying?”

“We’re not sure,” said Ronnie. “A week, maybe?”

Belinda shook her head. “Sorry, no. Out of the question.”

“I’m, uh, not sure I understand …”

“There is a town festival,” Belinda said, “for townsfolk only. You can stay until Wednesday morning, but will then have to leave.”

“We can do that,” said Linda. “What does the festival celebrate?”

“The town.”

Linda smiled and nodded. “And it is surely a town worth celebrating.”

“A question, if you please,” said Warrick, squeezing between them. Belinda recoiled slightly. “This motel. Is it pet friendly?”

“I’m sorry?”

“Is it friendly to pets? For instance, my dog. Is it friendly to my dog?”

Belinda looked horrified. “Are you asking if your dog is allowed inside the hotel?”

“That is what I’m asking, yes.”

“No.”

“Is that a ‘No, my dog is allowed,’ or a ‘No, my dog isn’t allowed’?”

“No pets are allowed on the premises,” said Belinda. “My brother is extremely allergic. Having an animal under this roof could kill him.”

“What if I told you he was house-trained?”

“Absolutely not.”

“What if I told you he would not try to have sex with any potted plants you may possess, or any of your favourite stuffed animals? Still no? Then I will be forced to sleep with him in our van. Is that what you want? Me sleeping in a van? This isn’t California, let me remind you. This is Alaska. It gets cold here. You’re really okay with me spending the night in a van, freezing to death while my oversexed dog humps my head?”

“Animals are not allowed.”

“What if we sneak him in without you noticing?”

“We’re not going to do that,” Ronnie said quickly.

Warrick nodded, and did the air quotes thing. “Yeah, we’re ‘not’.”

“We’re actually not,” said Linda. “If Warrick won’t go anywhere without that dog, he can sleep in the van and take the consequences. The rest of us would like beds, please – until Wednesday.”

“When you will depart,” said Belinda.

“When we will depart,” echoed Linda.

They were shown to their rooms and Kelly dumped her bag on her bed and went to the bathroom while Linda showered quickly. Then they switched, and got changed, and met the guys outside.

They drove through town, familiarising themselves with the layout before focusing on the quieter streets. They followed the few small scrawls of graffiti like it was a trail of breadcrumbs, losing it sometimes and having to double back to pick up the trail again. It took them the rest of the afternoon, but finally the trail led them all the way to a park, at the bottom of the hill that led to the motel.

“Well, that was a waste of time,” said Kelly.

They got out, went walking. Kelly zipped up her jacket while Two ran in excited circles. On the east side of the park there was a small building that housed the public restrooms. Facing the park, it was a pristine example of a public utility that was kept up to snuff. But the interesting stuff was all across the back in layers of names and promises and oaths and declarations.