Полная версия

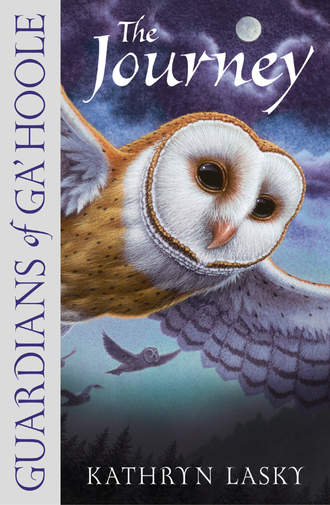

The Journey

“Left the nest a year ago. Still nearby,” said Swatums, the male. “But who knows, Sweetums might come up with another clutch of eggs in the new breeding season. And if she doesn’t, well, we two are enough company for each other.” Then they began preening each other.

It seemed to Soren and Gylfie that they preened incessantly. They always had their beaks in each other’s feathers, except, of course, when they were hunting. And when they were hunting they were exceptional killers. It was as predators that these Sooty Owls became the most interesting. Sweetums and Swatums were simply deadly, and Soren had to admit he had never eaten so well. Twilight had told them to watch carefully, for Sooty Owls were among the rare owls that went after tree prey and not just ground prey.

So tonight they were all feasting on three of a type of possum that they called sugar gliders. They were the sweetest things that any of the young band of owls had ever tasted. Maybe that was why the two Sooties called each other Sweetums and Swatums. They had simply eaten too many sweet things. Perhaps eating a steady diet of sugar gliders made an owl ooze with gooiness. Soren thought he was going to go stark raving yoicks if he had to listen to their gooey talk a moment longer, but luckily they were now, in their own boring way, discussing the Great Ga’Hoole Tree.

Sweetums was questioning her mate. “Well, what do you mean, Swatums, by ‘not exactly’? Isn’t it either a legend or not? I mean, it’s not really real.”

“Well, Sweetums, some say it’s simply invisible.”

“What’s simple about being invisible?” Gylfie asked.

“Ohh, hooo-hooo.” The two Sooty Owls were convulsed with laughter. “Doesn’t she remind you of Tibby, Swatums?” Then there was more cooing and giggling and disgusting preening. Soren felt that Gylfie’s question was a perfectly sensible one. What, indeed, was simple about invisibleness?

“Well, young’uns,” Swatums answered, “there is nothing simple. It’s just that it has been said that the Great Ga’Hoole Tree is invisible. That it grows on the island in the middle of a vast sea, a sea called Hoolemere that is nearly as wide as an ocean. A sea that is always wrapped in fog, an island feathered in blizzards and a tree veiled in mist.”

“So,” said Twilight, “it’s not really invisible, it’s just bad weather.”

“Not exactly,” replied Swatums. Twilight cocked his head. “It seems that for some the fog lifts, the blizzards stop and the mist blows away.”

“For some?” asked Gylfie.

“For those who believe.” Swatums paused and then sniffed in disdain. “But do they say what? Believe in what? No. You see, that is the problem. Owls with fancy ideas – ridiculous! That’s how you get into trouble. Sweetums and I don’t believe in fancy ideas. Fancy ideas don’t keep the belly full and the gizzard grinding. Sugar gliders, plump rats, voles – that’s what counts.” Sweetums nodded and Swatums went over and began preening her for the millionth time that day.

Soren knew in that moment that even if he were starving to death, he would still find Sweetums and Swatums the most boring owls on Earth.

That late afternoon as they nestled in the hollow, waiting for First Black, Gylfie stirred sleepily. “You awake, Soren?”

“Yeah. I can’t wait to get to Hoolemere.”

“Me neither. But I was wondering,” Gylfie said.

“Wondering what?”

“Do you think that Streak and Zan love each other as much as Sweetums and Swatums?” Streak and Zan were two Bald Eagles who had helped them in the desert when Digger had been attacked by the lieutenants from St Aggie’s – the very ones who had earlier eaten Digger’s brother, Flick. The two eagles had seemed deeply devoted to each other. Yet Zan could not utter a sound. Her tongue had been torn out in battle.

What an interesting question, Soren thought. His own parents never preened each other as constantly as Sweetums and Swatums, and they hadn’t called each other gooey names, but he had never doubted their love for each other. “I don’t know,” he replied. “It’s hard thinking about mates. I mean, can you imagine ever having a mate or what he might be like?”

There was a long pause. “Honestly, no,” replied Gylfie.

They heard Twilight stir in his sleep.

“If I never taste another sugar glider it will be too soon.” Digger belched softly. “They keep repeating on me.”

The four owls had left at First Black and bid their farewells to the Sooties. They had now alighted on a tree limb with a good view down the valley. They were looking for a creek – any creek that could feed into a river that hopefully would be the River Hoole, which they could follow to the Sea of Hoolemere.

“What do you mean ‘keep repeating on you’?” Soren asked, imagining little possums gliding in and out of Digger’s beak.

“Just an expression. My dad used to say that after he ate centipedes.” Digger sighed. “And then Ma would say, ‘Well, of course they keep repeating on you, dear. You eat something that has all those legs, they’re probably still running around inside you’.”

Gylfie, Twilight and Soren burst out laughing.

Digger sighed again. “My mum was really funny. I miss her jokes.”

“Come on,” said Gylfie. “You’ll be OK.”

“But everything is so different here. I don’t live in trees. Never have in my life. I’m a Burrowing Owl. I lived in desert burrows. I don’t hunt these silly creatures that glide and fly about through the limbs. I miss the taste of snake and crawly things that pick up the dirt. Whoops, sorry, Mrs P.”

“Don’t apologise, Digger. Most owls do eat snakes – not usually blind snakes, since we tend their nests – but other snakes. Soren’s parents were particularly sensitive and, out of respect for me, would not eat any snake.”

Twilight had hopped to a higher limb to see if he could see any trace of a creek that might lead to a river.

“He’s not going to be able to see anything in this light. I don’t care how good his eyes are. A black trickle of a creek in a dark forest – forget it,” Gylfie said.

Suddenly, Soren cocked his head, first one way, then the other.

“What is it, Soren?” Digger asked.

“You hear something?” Twilight flew down and landed on a thin branch that creaked under his weight.

“Hush!” Soren said.

They all fell silent and watched as the Barn Owl tipped, cocked and pivoted his head in a series of small movements. And, finally, Soren heard something. “There is a trickle. I hear it. It’s not a lot of water, but I can hear that it begins in reeds and then it starts to slide over stones.”

Barn Owls were known for their extremely sensitive hearing. They could contract and expand the muscles of their facial disks to funnel the sound source to their unevenly placed earholes. The other owls were in awe of their friend’s abilities.

“Let’s go. I’ll lead,” Soren said.

It was one of the few times anyone except Twilight had flown in the point position.

As Soren flew, he kept angling his head so that his two ears, one lower and one higher, could precisely locate the source of the water. Within a few minutes, they had found a trickle and that trickle turned into a stream, a stream full of the music of gently tumbling water. Then by dawn that stream had become a river – the River Hoole.

“A masterful job of triangulation,” Gylfie cried. “Simply masterful, Soren. You are a premier navigator.”

“What’s she saying?” Digger asked.

“She’s saying that Soren got us here. Big words, little owl.” But it was evident that Twilight was impressed.

“So now what do we do?” Digger asked.

“Follow the river to the Sea of Hoolemere,” Twilight said. “Come on. We still have a few hours until First Light.”

“More flying?” Digger asked.

“What? You want to walk?” Twilight replied.

“I wouldn’t mind. My wings are tired. And it’s not just my wound. It’s healed.”

The three other owls stared at Digger in dismay. Gylfie hopped out on the tree branch they had landed on and peered intently at Digger. “Wings don’t get tired. That’s impossible.”

“Well, mine do. Can’t we rest up a bit?” Burrowing Owls, like Digger, were in fact known for their running abilities. Blessed with long, featherless legs, they could stride across the deserts as well as fly over them. But their flight skills were not as strong as those of other owls.

“I’m hungry, anyway,” said Soren. “Let me see if I can catch us something.”

“Please, no sugar gliders,” Digger added.

CHAPTER THREE

Twilight Shows Off

They had settled into the hollow of a fir tree and were eating some voles that Soren had brought back from his hunting expedition.

“Refreshing, isn’t it, after sugar gliders?” Gylfie said.

“Hmmm!” Digger smacked his beak and made a satisfied sound.

“What do you think the Great Ga’Hoole Tree will be like?” Soren said dreamily, as a little bit of vole tail hung from his beak.

“Different from St Aggie’s, that’s for sure,” Gylfie offered.

“Do you think they know about St Aggie’s – the raids, the egg snatching, the … the …” Soren hesitated.

“The cannibalism,” Digger said. “You might as well say it, Soren. Don’t try to protect me. I’ve seen the worst and I know it.”

They had all seen the worst.

Twilight, who was huge to start with, was beginning to swell up in fury. Soren knew what was coming. Twilight was not thinking about the owls of Ga’Hoole, those noble guardian knights of the sky. He was thinking about those ignoble, contemptible, basest of the base, monstrous owls of St Aggie’s. Twilight had been orphaned so young that he had not the slightest scrap of memory of his parents. For a long time, he had led a kind of vagabond, orphan life. Indeed, Twilight had lived with all sorts of odd animals, even a fox at one point, which was why he never hunted fox.

Like all Great Greys, he was considered a powerful and ruthless predator, but Twilight prided himself on being, as he called it, an owl from the Orphan School of Tough Learning. He was completely self-taught. He had lived in burrows with foxes, flown with eagles. He was strong and a real fighter. And there was not a modest hollow bone in Twilight’s body. He was powerful, a brilliant flier, and he was fast. As fast with his talons as with his beak. In a minute they all knew that the air would become shrill as he sang his own praises and jabbed and stabbed at an imaginary foe. Twilight’s shadow began to flicker in the dim light of the hollow as his voice, deep and thrumming, started to chant.

We’re going to bash them birds,

Them rat-feathered birds.

Them bad-butt owls ain’t never heard

’Bout Gylfie, Soren, Dig and Twilight.

Just let them get to feel my bite

Their li’l ol’ gizzards gonna turn to pus

And our feathers hardly mussed.

Oh me. Oh my. They gonna cry.

One look at Twilight,

They know they’re gonna die.

I see fear in their eyes

And that ain’t all.

They know that Twilight’s got the gall.

Gizzard with gall that makes him great

And every bad owl gonna turn to bait.

Jab, jab – then a swipe and hook with the right talon. Twilight danced around the hollow. The air churned with his shadow fight, and Gylfie, the tiniest of them all, had to hang on tight. It was like a small hurricane in the hollow. Then, finally, his movements slowed and he pranced off into a corner.

“Got that out of your system, Twilight?” Gylfie asked.

“What do you mean ‘out of my system’?”

“Your aggression.”

Twilight made a slightly contemptuous sound that came from the back of his throat. “Big words, little owl.” This was something Twilight often said to Gylfie. Gylfie did have a tendency to use big words.

“Well now, young’uns,” Mrs P was speaking up. “Let’s not get into it. I think, Gylfie, that in the face of cannibalism, aggression or going stark raving yoicks and absolutely annihilating the cannibals is perfectly appropriate.”

“More big words but I like them. I like them, Mrs P,” Twilight hooted his delight.

Soren, however, remained quiet. He was thinking. He was still wondering what the Great Ga’Hoole Tree would be like. What would those noble owls think of an owl like Twilight – so unrefined, yet powerful. So cheeky, but loyal – so angry, but true?

CHAPTER FOUR

Get Out! Get Out!

They had left the hollow of the fir tree at First Black. The night was racing with ragged clouds. The forest covering was thick beneath them so they flew low to keep the River Hoole in sight, which sometimes narrowed and only appeared as the smallest glimmer of a thread of water. The trees thinned and Twilight said that he thought the region below was known as The Beaks. For a while, they seemed to lose the strand of the river, and there appeared to be many other small threadlike creeks or tributaries. They were, of course, worried they might have lost the Hoole, but if they had their doubts they dared not even think about them for a sliver of a second. For doubts, each one feared in the deepest parts of their quivering gizzards, might be like an owl sickness – like greyscale or beak rot – contagious and able to spread from owl to owl.

How many false creeks, streams and even rivers had they followed so far, only to be disappointed? But now Digger called out, “I see something!” All of their gizzards quickened. “It’s, it’s … whitish … well, greyish.”

“Ish? What in Glaux’s name is ‘ish’?” Twilight hooted.

“It means,” Gylfie said in her clear voice, “that it’s not exactly white, and it’s not exactly grey.”

“I’ll have a look. Hold your flight pattern until I get back.”

The huge Great Grey Owl began a power dive. He was not gone long before he returned. “And you know why it’s not exactly grey and not exactly white?” Twilight did not wait for an answer. “Because it’s smoke.”

“Smoke?” The other three seemed dumbfounded.

“You do know what smoke is?” Twilight asked. He tried to remember to be patient with these owls who had seen and experienced so much less than he had.

“Sort of,” Soren replied. “You mean there’s a forest fire down there? I’ve heard of those.”

“Oh, no. Nothing that big. Maybe once it was. But, really, the forests of The Beaks are minor ones. Second-rate. Few and far between and not much to catch fire.”

“Spontaneous combustion – no doubt,” Gylfie said. Twilight gave the little Elf Owl a withering look. Always trying to steal his show with the big words. He had no idea what spontaneous combustion was and he doubted if Gylfie did, either. But he let it go for the moment. “Come on, let’s go explore.”

They alighted on the forest floor at the edge of where the smoke was the thickest. It seemed to be coming out of a cave beneath a stone outcropping. There was a scattering of a few glowing coals on the ground and charred pieces of wood. “Digger,” Twilight said, “can you dig as well as you can walk with those naked legs of yours?”

“You bet. How do you think we fix up our burrows or make them bigger? We don’t just settle for what we happen upon.”

“Well, start digging and show the rest of us how. We’ve got to bury these coals before a wind comes up and carries them off and really gets a fire going.”

It was hard work burying the coals, especially for Gylfie, who was the tiniest and had the shortest legs of all. “I wonder what happened here?” Gylfie said as she paused to look around. Her eyes settled on what she thought was a charred piece of wood, but something glinted through the blackness of the moonless night. Glinted and curved into a familiar shape. Gylfie blinked. Her gizzard gave a little twitch and as if in a trance she walked over towards the object.

“Battle claws!” she gasped. From inside the cave came a terrible moan. “Get out! Get out!”

But they couldn’t get out! They couldn’t move. Between them and the mouth of the cave, gleaming eyes, redder than any of the live coals, glowered and there was a horrible rank smell. Two curved white fangs sliced the darkness.

“Bobcat!” Twilight roared.

The four owls simultaneously lifted their eight wings in powerful upstrokes. The bobcat shrieked below, a terrible sky-shattering shriek. Soren had never heard anything like it. It had all happened so suddenly that Soren had even forgotten to drop the coal that he had in his beak.

“Good Glaux, Soren!” Gylfie said as she saw her dear friend’s face bathed in the red light of the radiant coal.

Soren dropped it immediately.

There was another shriek. A shadow blacker than the night seemed to leap into the air, then plummet to the ground, writhing and yowling in pain.

“Well, bust my gizzard!” Twilight shouted. “Soren, you dropped that coal right on the cat! What a shot!”

“I – what?”

“Come on, we’re going in for him – for the kill.”

“The kill?” Soren said blankly.

“Follow me. Aim for his eyes. Gylfie, stay clear of his tail. I’ll go for the throat. Digger, take a flank.”

The four owls flew down in a deadly wedge. Soren aimed for the eyes, but one was already useless, as the coal had done its work and a still-sizzling socket wept small embers. Digger sunk his talons into an exposed flank as the bobcat writhed on the ground, and Gylfie stuck one of her talons down the largest nostril that Soren had ever seen. Twilight made a quick slice at the throat and blood spattered the night. The cat was no longer howling. It lay in a heap on the forest floor, its face smouldering from the coal. The smell of singed fur filled the night as the bobcat’s pulse grew weaker and the blood poured out from the deep gash in its throat.

“Was he after the battle claws – a bobcat?” Soren turned to Gylfie.

When the two owls had been at St Aggie’s, Grimble, the old Boreal Owl who had died helping them escape, had told them how the warriors of St Aggie’s could not make their own battle claws so they scavenged them from battlefields. But a bobcat? Why would a bobcat need battle claws? They stared at the long sharp claws that extended from the paws of the cat and looked deadlier than any battle claws.

“No,” Twilight said quietly. He had flown over to the cave and now stood in its opening. “The cat was after what was in here.”

“What’s that?” the three other owls asked at once.

“A dying owl,” Mrs Plithiver said as she slithered out from the cave where she had taken refuge. “Come in. I think he wants to speak, if he has any more breath in him.”

The owls moved into the cave opening. There was a mass of brown feathers collapsed by a shallow pit that still glowed with embers. It was a Barred Owl. Although that was hard to tell, for the white bars of his plumage were bloodstained and his beak seemed to jut out at a peculiar angle. “Don’t blame the cat,” the Barred Owl moaned. “Only here after … after … they—”

“After they what, sir?” Gylfie stepped closer to the skewed beak and bent her head to better hear the weak voice.

“They wanted the battle claws, didn’t they?” Soren bobbed his head down towards the dying owl. Did he move his head slightly as if to nod? But the Barred Owl’s breath was going, was growing shallower.

“Was it St Aggie’s?” Glyfie spoke softly.

“I wish it had been St Aggie’s. It was something far worse. Believe me – if St Aggie’s – Oh! You only wish!” The owl sighed and was dead.

The four owls blinked at one another and were silent for several moments. “You only wish!” Digger repeated. “Does he mean there’s something worse than St Aggie’s?”

“How could there be?” Soren said.

“What is this place?” Gylfie said. “Why are there battle claws here but it isn’t a battlefield? If it had been, we would have seen other owls, wounded or dead.”

They turned towards the Great Grey. “Twilight?” Soren asked.

But for once, Twilight seemed stumped. “I’m not sure. I’ve heard tell of owls – very clever owls that live apart, never mate, not really belonging to any kingdom. Do for themselves for the most part. Sometimes hire out for battles. Hireclaws, I think they call them. Maybe this was one. And The Beaks is a funny place, you know. Not many forests. Mostly ridges like the ones we’ve been flying over the last day or so. A few woods in between. So not a lot of places for owls to end up. No really big trees with big hollows. Probably a real loner, this fellow.”

They looked down at the dead Barred Owl.

“What should we do with him?” Soren asked. “I hate to leave him here for the next bobcat to come along. He tried to warn us, after all. He said, ‘Get out! Get out!’”

It was Digger who spoke next in a quavery voice. “And, you know, I don’t think he was warning us about the bobcat.”

“You think,” Gylfie said in a quiet steady voice, “that it was about these others, the ones worse than St Aggie’s?”

Digger nodded.

“But we can’t just leave him. This was a brave owl … a noble owl.” Soren spoke vehemently, “He was noble even if he didn’t live at the Great Tree as a knightly owl.”

Twilight stepped forwards. “Soren’s right. He was a brave owl. I don’t want to leave him for dirty old scavengers. If it’s not the bobcats, it’ll be the crows; if not crows, vultures.”

“But what can we do with him?” Digger said.

“I’ve heard of burial hollows, high up in trees,” Twilight said. “When I was with a Whiskered Screech family in Ambala that’s what they did when their grandmother died.”

“It’s going to take too long to find a hollow in The Beaks,” Gylfie now spoke. “You said it yourself, Twilight – it’s a second-rate forest, no big trees.”

Soren was looking around. “This owl lived in this cave. Look, you can tell. There’s some fresh pellets just outside, and there’s a stash of nuts and over there, a vole killed not long ago – probably his next dinner … I think we should—”

“We can’t leave him in the cave,” Gylfie interrupted. “Even if it is his home. Another bobcat could come along and find him.”

“But Soren is right,” Digger said. “His spirit is here.” Digger was a very odd owl. Whereas most owls were consumed with the practical world of hunting, flying and nesting, Digger – with his legs better for running than his wings were for flying, with his inclination for burrows rather than hollows – was undeniably an impractical owl. But perhaps because he was not focused on the commonplace, the ordinary drudgeries and small joys of owl life, his mind was freer to range. And range it did into the sphere of the spiritual, of the meaning of life, of the possibilities of an afterlife. And it was the afterlife of the brave Barred Owl that seemed to concern him now. “His spirit is in this cave. I feel it.”

“So what do we do?” Twilight asked.

Soren looked around slowly at the cave. His dark eyes, like polished stones, studied the walls. “He had many fires in this cave. Look at the walls – as sooty as a Sooty Owl’s wings. I think he made things with fires in this pit right here. I think …” Soren spoke very slowly. “I think we should burn him.”

“Burn him?” the other three owls repeated quietly.

“Yes. Right here in this pit. The embers are still burning. It will be enough.” The owls nodded to one another in silent agreement. It seemed right.

So the four owls, as gently as they could, rolled the dead Barred Owl on to the coals with their talons.

“Do we have to stay and watch?” Gylfie asked as the first feathers began to ignite.

“No!” Soren said, and they all followed him out of the cave entrance and flew into the night.

They rose on a series of updrafts and then circled the clearing where the cave had been. Three times they circled as they watched the smoke curl out from the mouth of the cave. Mrs Plithiver moved forwards through the thick feathers of Soren’s shoulders and leaned out towards one of his ears. “I am proud of you, Soren. You have protected a brave owl against the indignities of scavengers.” Soren wasn’t sure what the word ‘indignities’ meant, but he hoped what they had done was right for an owl he believed to be noble. But would they ever find the Great Ga’Hoole Tree, where other noble owls lived? And now it was not doubt that began to prick at his gizzard, but the ominous words of the Barred Owl – “you only wish!”