Полная версия

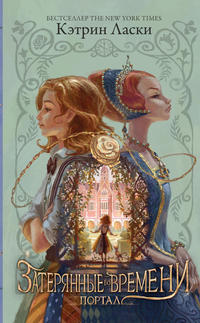

The Capture

“Soren … are you … are you alive? Oh dear, of course you are if you can say my name. How stupid of me. Are you well? Did you break anything?”

“I don’t think so, but how will I ever get back up there?”

“Oh dear oh dear!” Mrs Plithiver moaned. She was not much good in a crisis. One could not expect such things of nest-maids, Soren supposed.

“How long until Mum and Da get home?” Soren called up.

“Oh, it could be a long while, dearie.”

Soren had hop-stepped to the roots of the tree that ran above the ground like gnarled talons. He could now see Mrs Plithiver, her small head with its glistening rosy scales hovering over the edge of the hollow. Where Mrs Plithiver’s eyes should have been there were two small indentations. “This is simply beyond me,” she sighed.

“Is Kludd awake? Maybe he could help me.”

There was a long pause before Mrs Plithiver answered weakly, “Well, perhaps.” She sounded hesitant. Soren could hear her now, nudging Kludd. “Don’t be grumpy, Kludd. Your brother has … has … taken a tumble, as it were.”

Soren heard his brother yawn. “Oh my,” Kludd sighed and didn’t sound especially upset, Soren thought. Soon the large head of his big brother peered over the edge of the hollow. His white heart-shaped face with the immense dark eyes peered down on Soren. “I say,” Kludd drawled. “You’ve got yourself in a terrible fix.”

“I know, Kludd. Can’t you help? You know more about flying than I do. Can’t you teach me?”

“Me teach you? I wouldn’t know where to begin. Have you gone yoicks?” He laughed. “Stark-raving yoicks. Me teach you?” He laughed again. There was a sneer embedded deep within the laugh.

“I’m not yoicks. But you’re always telling me how much you know, Kludd.” This was certainly the truth. Kludd had been bragging about his superiority ever since Soren had hatched out. He should get the favourite spot in the hollow because he was already losing his downy fluff in preparation for his flight feathers and therefore would be colder. He deserved the largest hunks of mouse meat because he, after all, was on the brink of flying. “You’ve already had your First Flight ceremony. Tell me how to fly, Kludd.”

“One cannot tell another how to fly. It’s a feeling, and besides, it is really a job for Mum and Da. It would be very impertinent of me to usurp their position.”

Soren had no idea what “usurp” meant. Kludd often used big words to impress him.

“What are you talking about? Usurp?” Sounded like “yarp” to Soren. But what would yarping have to do with teaching him to fly? Time was running out. The light was leaking out of the day’s end and the evening shadows were falling. The raccoons would soon be out.

“I can’t do it, Soren,” Kludd replied in a very serious voice. “It would be extremely improper for a young owlet like myself to assume this role in your life.”

“My life isn’t going to be worth two pellets if you don’t do something. Don’t you think it is improper for you to let me die? What will Mum and Da say to that?”

“I think they will understand completely.”

Great Glaux! Understand completely! He had to be yoicks. Soren was simply too dumbfounded. He could not say another word.

“I’m going to get help, Soren. I’ll go to Hilda’s,” he heard Mrs P rasp. Hilda was another nest-maid snake for an owl family in a tree near the banks of the river.

“I wouldn’t if I were you, P.” Kludd’s voice was ominous. It made Soren’s gizzard absolutely quiver.

“Don’t call me P. That’s so rude.”

“That’s the last thing you have to worry about P – me being rude.”

Soren blinked.

“I’m going, Kludd. You can’t stop me,” Mrs Plithiver said firmly.

“Can’t I?”

Soren heard a rustling sound above. Good Glaux, what was happening?

“Mrs Plithiver?” Only silence now. “Mrs Plithiver?” Soren called again. Maybe she had gone to Hilda’s. He could only hope, and wait.

It was nearly dark now and a chill wind rose up. There was no sign of Mrs Plithiver returning. “First teeth” – isn’t that what Da always called these early cold winds? – the first teeth of winter. The very words made poor Soren shudder. When his father had first used this expression, Soren had no idea what “teeth” even were. His father explained that they were something that owls didn’t have, but most other animals did. They were for tearing and chewing food.

“Does Mrs Plithiver have them?” asked Soren. Mrs Plithiver had gasped in disgust.

His mother said, “Of course not, dear.”

“Well, what are they exactly?” Soren had asked.

“Hmm,” said his mother as she thought a moment. “Just imagine a mouth full of beaks – yes, very sharp beaks.”

“That sounds very scary.”

“Yes, it can be,” his mother replied. “That is why you do not want to fall out of the hollow or try to fly before you’re ready, because raccoons have very sharp teeth.”

“You see,” his father broke in, “we have no need for such things as teeth. Our gizzards take care of all that chewing business. I find it rather revolting, the notion of actually chewing something in one’s mouth.”

“They say it adds flavour, darling,” his mother added.

“I get flavour, plenty of flavour, in my gizzard. Where do you think that old expression ‘I know it in my gizzard’ comes from? Or ‘I have a feeling in my gizzard’, Marella?”

“Noctus, I’m not sure if that is the same thing as flavour.”

“That mouse we had for dinner last night – I can tell you from my gizzard exactly where he had been of late. He had been feasting on the sweet grass of the meadow mixed with the nooties from that little Ga’Hoole tree that grows down by the stream. Great Glaux! I don’t need teeth to taste.”

Oh dear, thought Soren, he might never hear this gentle bickering between his parents again. A centipede pittered by and Soren did not even care. Darkness gathered. The black of the night grew deeper and from down on the ground he could barely see the stars. This perhaps was the worst. He could not see sky through the thickness of the trees. How much he missed the hollow. From their nest, there was always a little piece of the sky to watch. At night, it sparkled with stars or raced with clouds. In the daytime, there was often a lovely patch of blue, and sometimes towards evening, before twilight, the clouds turned bright orange or pink. There was an odd smell down here on the ground – damp and mouldy. The wind sighed through the branches above, through the leaves and the needles of the forest trees, but down on the ground … well, the wind didn’t seem to even touch the ground. There was a terrible stillness. It was the stillness of a windless place. This was no place for an owl to be. Everything was different.

If his feathers had been even half-fledged, he could have plumped them up and the downy fluff beneath the flight feathers would have kept him warm. He supposed he could try calling for Eglantine. But what use would she be? She was so young. Besides, if he called out, wouldn’t that alert other creatures in the forest that he was here? Creatures with teeth!

He guessed his life wasn’t worth two pellets. But even worthless, he still missed his parents. He missed them so much that the missing felt sharp. Yes, he did feel something in his gizzard as sharp as a tooth.

CHAPTER THREE

Snatched!

Soren was dreaming of teeth and of the heartbeats of mice when he heard the first soft rustlings overhead. “Mum! Da!” he cried out in his half sleep. He would forever regret calling out those two words, for suddenly, the night was ripped with a shrill screech and Soren felt talons wrap around him. Now he was being lifted. And they were flying fast, faster than he could think, faster than he could ever imagine. His parents never flew this fast. He had watched them when they took off or came back from the hollow. They glided slowly and rose in beautiful lazy spirals into the night. But now, underneath, the earth raced by. Slivers of air blistered his skin. The moon rolled out from behind thick clouds and bleached the world with an eerie whiteness. He scoured the landscape below for the tree that had been his home. But the trees blurred into clumps, and then the forest of the Kingdom of Tyto seemed to grow smaller and smaller and dimmer and dimmer in the night, until Soren could not stand to look down any more. So he dared to look up.

There was a great bushiness of feathers on the owl’s legs. His eyes continued upward. This was a huge owl – or was it even an owl? Atop this creature’s head, over each eye, were two tufts of feathers that looked like an extra set of wings. Just as Soren was thinking this was the strangest owl he had ever seen, the owl blinked and looked down. Yellow eyes! He had never seen such eyes. His own parents and his brother and sister all had dark, almost black eyes. His parents’ friends who occasionally flew by had brownish eyes, perhaps some with a tinge of tawny gold. But yellow eyes? This was wrong. Very wrong!

“Surprised?”

The owl blinked, but Soren could not reply. So the owl continued. “Yes, you see, that’s the problem with the Kingdom of Tyto – you never see any other kind of owl but your own kind – lowly, undistinguished Barn Owls.”

“That’s not true,” said Soren.

“You dare contradict me!” screeched the owl.

“I’ve seen Grass Owls and Masked Owls. I’ve seen Bay Owls and Sooty Owls. Some of my parents’ very best friends are Grass Owls.”

“Stupid! They’re all Tytos,” the owl barked at him.

Stupid? Grown-ups weren’t supposed to speak this way – not to young owls, not to chicks. It was mean. Soren decided he should be quiet. He would stop looking up.

“We might have a haggard here,” he heard the owl say. Soren turned his head slightly to see who the owl was speaking to.

“Oh, great Glaux! One wonders if it is worth the effort.” This owl’s eyes seemed more brown than yellow and his feathers were spattered with splotches of white and grey and brown.

“Oh, I think it is always worth the effort, Grimble. And don’t let Spoorn hear you talking that way. You’ll get a demerit and then we’ll all be forced to attend another one of her interminable lectures on attitude.”

This owl looked different as well. Not nearly as big as the other owl and his voice made a soft tingg-tingg sound. It was at least a minute before Soren noticed that this owl was also carrying something in his talons. It was a creature of some sort and it looked rather owlish, but it was so small, hardly larger than a mouse. Then it blinked its eyes. Yellow! Soren resisted the urge to yarp. “Don’t say a word!” the small owl said in a squeaky whisper. “Wait.”

Wait for what? Soren wondered. But soon he felt the night stir with the beating of other wings. More owls fell in beside them. Each one carried an owlet in its talons. Then there was a low hum from the owl that gripped Soren. Gradually, the other owls flanking them joined in. Soon the air thrummed with a strange music. “It’s their hymn,” whispered the tiny owl. “It gets louder. That’s when we can talk.”

Soren listened to the words of the hymn.

Hail to St Aegolius

Our Alma Mater.

Hail, our song we raise in praise of thee

Long in the memory of every loyal owl

Thy splendid banner emblazoned be.

Now to thy golden talons

Homage we’re bringing.

Guiding symbol of our hopes and fears

Hark to the cries of eternal praises ringing

Long may we triumph in the coming years.

The tiny owl began to speak as the voices swelled in the black of the night. “My first words of advice are to listen rather than speak. You’ve already got yourself marked as a wild owl, a haggard.”

“Who are you? What are you? Why do you have yellow eyes?”

“You see what I mean! That is the last thing that you should worry about.” The tiny owl sighed softly. “But I’ll tell you. I am an Elf Owl. My name is Gylfie.”

“I’ve never seen one in Tyto.”

“We live in the high desert kingdom of Kuneer.”

“Do you ever grow any bigger?”

“No. This is it.”

“But you’re so small and you’ve got all of your feathers, or almost.”

“Yes, this is the worst part. I was within a week or so of flying when I got snatched.”

“But how old are you?”

“Twenty nights.”

“Twenty nights!” Soren exclaimed. “How can you fly that young?”

“Elf Owls are able to fly by twenty-seven or thirty nights.”

“How much is sixty-six nights?” Soren asked.

“A lot.”

“I’m a Barn Owl and we can’t fly for sixty-six nights. But what happened to you? How did you get snatched?”

Gylfie did not answer right away. Then slowly, “What is the ONE thing that your parents always tell you not to do?”

“Fly before you’re ready?” Soren said.

“I tried and I fell.”

“But I don’t understand. It would have been only a week, you said.” Soren, of course, wasn’t sure how long a week was or how long twenty-seven nights were, but it all sounded shorter than sixty-six.

“I was impatient. I was well on my way to growing feathers but had grown no patience.” Gylfie paused again. “But what about yourself? You must have tried it too.”

“No. I don’t really know what happened. I just fell out of the nest.” But the second Soren said those words he felt a weird queasiness. He almost knew. He just couldn’t quite remember, but he almost knew how it had happened, and he felt a mixture of dread and shame creep through him. He felt something terrible deep in his gizzard.

CHAPTER FOUR

St Aegolius Academy for Orphaned Owls

The owls began to bank in steep turns as they circled downwards. Soren blinked and looked down. There was not a tree, not a stream, not a meadow. Instead, immense rock needles bristled up, and cutting through them were deep stone ravines and jagged canyons. This could not be Tyto. That was all that Soren could think.

Down, down, down they plunged in tighter and tighter circles, until they alighted on the stony floor of a deep, narrow canyon. And although Soren could indeed see the sky from which they had just plunged, it seemed farther away than ever. Above, there was the sound of wind, distant yet shrill as it whistled across the upper reaches of this harsh stone world. Then, piercing through the shriek of the wind, came a voice even louder and sharper.

“Welcome, owlets. Welcome to St Aegolius. This is your new home. It is here that you will find truth and purpose. Yes, that is our motto. When Truth Is Found, Purpose Is Revealed.”

The immense, ragged Great Horned Owl fixed them in her yellow gaze. The tufts above her eyes swooped up. The shoulder feathers on her left wing had separated, revealing an unsightly patch of skin with a jagged white scar. She was perched on a rock outcropping in the granite ravine where they had been brought. “I am Skench, Ablah General of St Aegolius. My job is to teach you the Truth. We discourage questions here as we feel they often distract from the Truth.” Soren found this very confusing. He had always asked questions, ever since he had hatched out.

Skench, the Ablah General, was continuing her speech. “You are orphans now.” The words shocked Soren. He was not an orphan! He had a mum and da, perhaps not here, but out there somewhere. Orphan meant your parents were dead. How dare this Skench, the Ablah blah blah blah or whatever she called herself, say he was an orphan!

“We have rescued you. It is here at St Aggie’s that you shall find everything that you need to become humble, plain servants of a higher good.”

This was the most outrageous thing Soren had ever heard. He hadn’t been rescued, he had been snatched away. If he had been rescued, these owls would have flown up and dropped him back in his family’s nest. And what exactly was a higher good?

“There are many ways in which one can serve the higher good, and it is our job to find out which best suits you and to discover what your special talents are.” Skench narrowed her eyes until they were gleaming amber slits in her feathery face. “I am sure that each and every one of you has something special.”

At that very moment, there was a chorus of hoots and many owl voices were raised in song.

To find one’s special quality

One must lead a life of deep humility.

To serve in this way

Never question but obey

Is the blessing of St Aggie’s charity.

At the conclusion of the short song Skench, the Ablah General, swooped down from her stone perch. She fixed them all in the glare of her eyes. “You are embarking on an exciting adventure, little orphans. After I have dismissed you, you shall be led to one of four glaucidiums, where two things shall occur. You shall receive your number designation. And you shall also receive your first lesson in the proper manner in which to sleep and shall be inducted into the march of sleep. These are the first steps towards the Specialness ceremony.”

What in the world was this owl talking about? Soren wondered. Number designation? What was a glaucidium, and since when did an owl have to be taught to sleep? And a sleep march? What was that? And it was still night. What owl slept at night? But before he could really ponder these questions, he felt himself being gently shoved into a line, a separate line from the little Elf Owl called Gylfie. He turned his head nearly completely around to search for Gylfie and caught sight of her. He raised a stubby wing to wave but Gylfie did not see him. He saw her marching ahead with her eyes looking straight ahead.

The line Soren was in wound its way through a series of deep gorges. It was like a stone maze of tangled trails through the gaps and canyons and notches of this place called St Aegolius Academy for Orphaned Owls. Soren had the unsettling feeling that he might never see the little Elf Owl again and, even worse, it would be impossible to ever find one’s way out of these stone boxes into the forest world of Tyto, with its immense trees and sparkling streams.

They finally came to stop in a circular stone pit. A white owl with very thick feathers waddled towards them and blinked. Her eyes had a soft yellow glow.

“I am Finny, your pit guardian.” And then she giggled softly. “Some have been known to call me their pit angel.” She gazed sweetly at them. “I would love it if you would all call me Auntie.”

Auntie? Soren wondered. Why would I ever call her Auntie? But he remembered not to ask.

“I must, of course, call you by your number designation, which you shall shortly be told,” said Finny.

“Oh, goody!” A little Spotted Owl standing next to Soren hopped up and down.

This time, Soren remembered too late that questions were discouraged. “Why do you want a number instead of your name?”

“Hortense! You wouldn’t like that name, either,” the Spotted Owl whispered. “Now, shush. Remember, no questions.”

“You shall, of course,” Finny continued, “if you are good humble owlets and learn the lessons of humility and obedience, earn your Specialness rank and then receive your true name.”

But my true name is Soren. It is the name my parents gave me. The words pounded in Soren’s head and even his gizzard seemed to tremble in protest.

“Now, let’s line up for our Number ceremony, and I have a tempting little snack here for you.”

There were perhaps twenty owls in Soren’s group and Soren was towards the middle of the line. He watched as the white owl, Auntie or Finny, whom Hortense had informed him was a Snowy Owl, dropped a piece of fur-stripped mouse meat on the stone before each owl in turn and then said, “Why, you’re number 12-6. What a nice number that is, dearie.”

Every number was either “nice” or “dear” or “darling”. Finny bent her head solicitously and often gave a friendly little pat to the owlet just “numbered”. She was full of quips and little jokes. Soren was just beginning to feel that things perhaps could be worse, and he hoped that Gylfie had such a nice owl for a pit guardian, when the huge fierce owl with the tufts over each eye, the very one who had snatched him and called him stupid, alighted down next to Finny. Soren felt a cold dread steal over his gizzard as he saw the owl look directly at him and then dip his head and whisper something into Finny’s ear. Finny nodded and looked at him blandly. They were talking about him. Soren was sure. He could barely move his talons forwards on the hard stone towards Finny. His turn was coming up soon. Only four more owls before he would be “numbered”.

“Hello, sweetness,” Finny cooed as Soren stepped forwards. “I have a very special number for you!” Soren was silent. Finny continued, “Don’t you want to know what it is?” This is a trick. Questions are discouraged. I’m not supposed to ask. And that was exactly what Soren said.

“I’m not supposed to ask.” The soft yellow glow streamed from Finny’s eyes. Soren felt a moment’s confusion. Then Finny leaned forwards and whispered to him. “You know, dear, I’m not as strict as some. So please, if you really really need to ask a question, just go ahead. But remember to keep your voice down. And here, dear, is a little extra piece of mouse. And your number …” She sighed and her entire white face seemed to glow with the yellow light. “My favourite – 12-1. Isn’t it sublime! It’s a very special number, and I am sure that you will discover your very own specialness as an owl.”

“Thank you,” Soren said, still slightly mystified but relieved that the fierce owl had apparently not told Finny anything bad about him.

“Thank you, what?” Finny giggled. “See? I get to ask questions too, sometimes.”

“Thank you, Finny?”

Finny inclined her head towards him again. There was a slight glare in the yellow glow. “Again,” she whispered softly. “Again … now, look me in the eyes.” Soren looked into the yellow light.

“Thank you, Auntie.”

“Yes, dear. I’m just an old broody. Love being called Auntie.”

Soren did not know what a broody was, but he took the mouse meat and followed the owl who had been in front of him into the glaucidium. Two large, ragged brown owls escorted the entire group. The glaucidium was a deep box canyon, the floor of which was covered with sleeping owlets. Moonlight streamed down directly on them, silvering their feathers.

“Fall in, you two!” barked a voice from high up in a rocky crevice.

“You!” A plump owl stepped up to Soren. Indeed, Soren’s heart quickened at first for it was another Barn Owl just like his own family. There was the white heart-shaped face and the familiar dark eyes. And yet, although the colour of these eyes was identical to his own and those of his family, he found the owl’s gaze frightening.

“Back row, and prepare to assume the sleeping position.” These instructions were delivered in the throaty rasp common to Barn Owls, but Soren found nothing comforting in the familiar.

The two owls who had escorted the newly arrived orphans spoke to them next. They were Long Eared Owls and had tufts that poked straight up over their eyes and twitched. Soren found this especially unnerving. They each alternated speaking in short deep whoos. The whoos were even more disturbing than the barks of Skench earlier, for the sound seemed to coil into Soren’s very breast and thrum with a terrible clang.

“I am Jatt,” said the first owl. “I was once a number. But now I have earned my new name.”

“Whhh—” Soren snapped off the word.

“I see a question forming on your disgusting beak, number 12-1!” The whoo thrummed so deep within Soren’s breast that he thought his heart might burst.