Полная версия

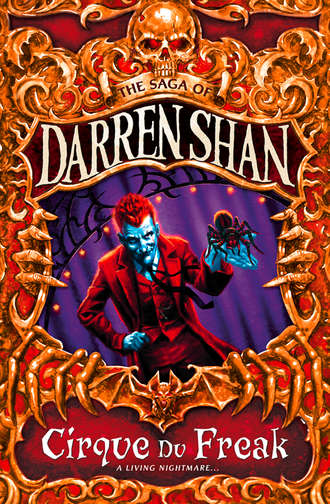

Cirque Du Freak

“Well, so much for that,” I said, putting on a brave face.

“Maybe not,” Steve said. “My mum keeps a wad of money in a jar at home. I could borrow some and put it back when we get our pocket money.”

“You mean steal?” I asked.

“I mean borrow,” he snapped. “It’s only stealing if you don’t put it back. What do you say?”

“How would we get the tickets?” Tommy asked. “It’s a school night. We wouldn’t be let out.”

“I can sneak out,” Steve said. “I’ll buy them.”

“But Mr Dalton snipped off the address,” I reminded him. “How will you know where to go?”

“I memorised it,” he grinned. “Now, are we gonna stand here all night making up excuses, or are we gonna go for it?”

We looked at each other, then – one by one – nodded silently.

“Right,” Steve said. “We hurry home, grab our money, and meet back here. Tell your parents you forgot a book or something. We’ll lump the money together and I’ll add the rest from the pot at home.”

“What if you can’t steal – I mean, borrow the money?” I asked.

He shrugged. “Then the deal’s off. But we won’t know unless we try. Now: hurry!”

With that, he sprinted away. Moments later, making up our minds, Tommy, Alan and me ran too.

CHAPTER FOUR

THE FREAK show was all I could think about that night. I tried forgetting it but couldn’t, not even when I was watching my favourite TV shows. It sounded so weird: a snake-boy, a Wolf Man, a performing spider. I was especially excited by the spider.

Mum and Dad didn’t notice anything was up, but Annie did. Annie is my younger sister. She can be a bit annoying but most of the time she’s cool. She doesn’t run to Mum telling tales if I misbehave, and she knows how to keep a secret.

“What’s wrong with you?” she asked after dinner. We were alone in the kitchen, washing up.

“Nothing’s wrong,” I said.

“Yes there is,” she said. “You’ve been behaving funny all night.”

I knew she’d keep asking until she got the truth, so I told her about the freak show.

“It sounds great,” she agreed, “but there’s no way you’d get in.”

“Why not?” I asked.

“I bet they don’t let children in. It sounds like a grown-up sort of show.”

“They probably wouldn’t let a brat like you in,” I said nastily, “but me and the others would be OK.” That upset her, so I apologised. “I’m sorry,” I said. “I didn’t mean that. I’m just annoyed because you’re probably right. Annie, I’d give anything to go!”

“I’ve got a make-up kit I could lend you,” she said. “You can draw on wrinkles and stuff. It’d make you look older.”

I smiled and gave her a big hug, which is something I don’t do very often. “Thanks, sis,” I said, “but it’s OK. If we get in, we get in. If we don’t, we don’t.”

We didn’t say much after that. We finished drying and hurried into the TV room. Dad got back home a few minutes later. He works on building sites all over the place, so he’s often late. He’s grumpy sometimes but was in a good mood that night and swung Annie round in a circle.

“Anything exciting happen today?” he asked, after he’d said hello to Mum and given her a kiss.

“I scored another hat trick at lunch,” I told him.

“Really?” he said. “That’s great. Well done.”

We turned the TV down while Dad was eating. He likes peace and quiet when he eats, and often asks us questions or tells us about his day at work.

Later, Mum went to her room to work on her stamp albums. She’s a serious stamp collector. I used to collect too, when I was younger and more easily amused.

I popped up to see if she had any new stamps with exotic animals or spiders on them. She hadn’t. While I was there, I sounded her out about freak shows.

“Mum,” I said, “have you ever been to a freak show?”

“A what?” she asked, concentrating on the stamps.

“A freak show,” I repeated. “With bearded ladies and wolf-men and snake-boys.”

She looked up at me and blinked. “A snake-boy?” she asked. “What on Earth is a snake-boy?”

“It’s a…” I stopped when I realised I didn’t know. “Well, that doesn’t matter,” I said. “Have you ever been to one?”

She shook her head. “No. They’re illegal.”

“If they weren’t,” I said, “and one came to town, would you go?”

“No,” she said, shivering. “Those sorts of things frighten me. Besides, I don’t think it would be fair on the people in the show.”

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“How would you like it,” she said, “if you were stuck in a cage for people to look at?”

“I’m not a freak!” I said huffily.

“I know,” she laughed, and kissed the top of my head. “You’re my little angel.”

“Mum, don’t!” I grumbled, wiping my forehead with my hand.

“Silly,” she smiled. “But imagine you had two heads or four arms, and somebody stuck you on show for people to make fun of. You wouldn’t like that, would you?”

“No,” I said, shuffling my feet.

“Anyway, what’s all this about a freak show?” she asked. “Have you been staying up late, watching horror films?”

“No,” I said.

“Because you know your Dad doesn’t like you watching—”

“I wasn’t staying up late, OK?” I shouted. It’s really annoying when parents don’t listen.

“OK, Mister Grumpy,” she said. “No need to shout. If you don’t like my company, go downstairs and help your father weed the garden.”

I didn’t want to go, but Mum was upset that I’d shouted at her, so I left and went down to the kitchen. Dad was coming in from the back and spotted me.

“So this is where you’ve been hiding,” he chuckled. “Too busy to help the old man tonight?”

“I was on my way,” I told him.

“Too late,” he said, taking off his wellies. “I’m finished.”

I watched him putting on his slippers. He has huge feet. He takes size 12 shoes! When I was younger, he used to stand me on his feet and walk me around. It was like being on two long skateboards.

“What are you doing now?” I asked.

“Writing,” he said. My dad has pen pals all over the world, in America, Australia, Russia and China. He says he likes to keep in touch with his global neighbours, though I think it’s just an excuse to go into his study for a nap!

Annie was playing with dolls and stuff. I asked if she wanted to come to my room for a game of bed-tennis using a sock for a ball, and shoes for rackets, but she was too busy arranging her dolls for a pretend picnic.

I went to my room and dragged down my comics. I have loads of cool comics, Superman, Batman, Spiderman and Spawn. Spawn’s my favourite. He’s a superhero who used to be a demon in Hell. Some of the Spawn comics are quite scary but that’s why I love them.

I spent the rest of the night reading comics and putting them in order. I used to swap with Tommy, who has a huge collection, but he kept spilling drinks on the covers and crumbs between the pages, so I stopped.

Most nights I go to bed by ten, but Mum and Dad forgot about me, and I stayed up until nearly half-past ten. Then Dad saw the light in my room and came up. He pretended to be cross but he wasn’t really. Dad doesn’t mind too much if I stay up late. Mum’s the one who nags me about that.

“Bed,” he said, “or I’ll never be able to wake you in the morning.”

“Just a minute, Dad,” I told him, “while I put my comics away and brush my teeth.”

“OK,” he said, “but make it quick.”

I stuck the comics into their box and stuffed it back up on the shelf over my bed.

I put on my pyjamas and went to brush my teeth. I took my time, brushed slowly, and it was almost eleven when I got into bed. I lay back, smiling. I felt very tired and knew I’d fall asleep in a couple of seconds. The last thing I thought about was the Cirque Du Freak. I wondered what a snake-boy looked like, and how long the bearded lady’s beard was, and what Hans Hands and Gertha Teeth did. Most of all, I dreamed about the spider.

CHAPTER FIVE

THE NEXT morning, Tommy, Alan and me waited outside the gates for Steve, but there was no sign of him by the time the bell rang for class, so we had to go in.

“I bet he’s dossing,” Tommy said. “He couldn’t get the tickets and now he doesn’t want to face us.”

“Steve’s not like that,” I said.

“I hope he brings the flyer back,” Alan said. “Even if we can’t go, I’d like to have the flyer. I’d stick it up over my bed and—”

“You couldn’t stick it up, stupid!” Tommy laughed.

“Why not?” Alan asked.

“Because Tony would see it,” I told him.

“Oh yeah,” Alan said glumly.

I was miserable in class. We had geography first, and every time Mrs Quinn asked me a question, I got it wrong. Normally geography’s my best subject, because I know so much about it from when I used to collect stamps.

“Had a late night, Darren?” she asked when I got my fifth question wrong.

“No, Mrs Quinn,” I lied.

“I think you did,” she smiled. “There are more bags under your eyes than in the local supermarket!” Everybody laughed at that – Mrs Quinn didn’t crack jokes very often – and I did too, even though I was the butt of the joke.

The morning dragged, the way it does when you feel let down or disappointed. I spent the time imagining the freak show. I made-believe I was one of the freaks, and the owner of the circus was a nasty guy who whipped everybody, even when they got stuff right. All the freaks hated him, but he was so big and mean, nobody said anything. Until one day, he whipped me once too often, and I turned into a wolf and bit his head off! Everybody cheered and I was made the new owner.

It was a pretty good daydream.

Then, a few minutes before break, the door opened and guess who walked in? Steve! His mother was behind him and she said something to Mrs Quinn, who nodded and smiled. Then Mrs Leonard left and Steve strolled over to his seat and sat down.

“Where were you?” I asked in a furious whisper.

“At the dentist’s,” he said. “I forgot to tell you I was going.”

“What about—”

“That’s enough, Darren,” Mrs Quinn said. I shut up instantly.

At break, Tommy, Alan and me almost smothered Steve. We were shouting and pulling at him at the same time.

“Did you get the tickets?” I asked.

“Were you really at the dentist’s?” Tommy wanted to know.

“Where’s my flyer?” Alan asked.

“Patience, boys, patience,” Steve said, pushing us away and laughing. “All good things to those who wait.”

“Come on, Steve, don’t mess us around,” I told him. “Did you get them or not?”

“Yes and no,” he said.

“What does that mean?” Tommy snorted.

“It means I have some good news, some bad news, and some crazy news,” he said. “Which do you want to hear first?”

“Crazy news?” I asked, puzzled.

Steve pulled us off to one side of the yard, checked to make sure no one was about, then began speaking in a whisper.

“I got the money,” he said, “and sneaked out at seven o’clock, when Mum was on the phone. I hurried across town to the ticket booth, but do you know who was there when I arrived?”

“Who?” we asked.

“Mr Dalton!” he said. “He was there with a couple of policemen. They were dragging a small guy out of the booth – it was only a small shed, really – when suddenly there was this huge bang and a great cloud of smoke covered them all. When it cleared, the small guy had disappeared.”

“What did Mr Dalton and the police do?” Alan asked.

“Examined the shed, looked around a bit, then left.”

“They didn’t see you?” Tommy asked.

“No,” Steve said. “I was well hidden.”

“So you didn’t get the tickets,” I said sadly.

“I didn’t say that,” he contradicted me.

“You got them?” I gasped.

“I turned to leave,” he said, “and found the small guy behind me. He was tiny, and dressed in a long cloak which covered him from head to toe. He spotted the flyer in my hand, took it, and held out the tickets. I handed over the money and—”

“You got them!” we roared delightedly.

“Yes,” he beamed. Then his face fell. “But there was a catch. I told you there was bad news, remember?”

“What is it?” I asked, thinking he’d lost them.

“He only sold me two,” Steve said. “I had the money for four, but he wouldn’t take it. He didn’t say anything, just tapped the bit on the flyer about “certain reservations”, then handed me a card which said the Cirque Du Freak only sold two tickets per flyer. I offered him extra money – I had nearly seventy pounds in total – but he wouldn’t accept it.”

“He only sold you two tickets?” Tommy asked, dismayed.

“But that means … ” Alan began.

“… only two of us can go,” Steve finished. He looked around at us grimly. “Two of us will have to stay at home.”

CHAPTER SIX

IT WAS Friday evening, the end of the school week, the start of the weekend, and everybody was laughing and running home as quick as they could, delighted to be free. Except a certain miserable foursome who hung around the schoolyard, looking like the end of the world had arrived. Their names? Steve Leonard, Tommy Jones, Alan Morris and me, Darren Shan.

“It’s not fair,” Alan moaned. “Who ever heard of a circus only letting you buy two tickets? It’s stupid!”

We all agreed with him, but there was nothing we could do about it apart from stand around, stubbing the ground with our feet, looking sour.

Finally, Alan asked the question which was on everybody’s mind.

“So, who gets the tickets?”

We looked at each other and shook our heads uncertainly.

“Well, Steve has to get one,” I said. “He put in more money than the rest of us, and he went to buy them, so he has to get one, agreed?”

“Agreed,” Tommy said.

“Agreed,” Alan said. I think he would have argued about it, except he knew he wouldn’t win.

Steve smiled and took one of the tickets. “Who goes with me?” he asked.

“I brought in the flyer,” Alan said quickly.

“Nuts to that!” I told him. “Steve should get to choose.”

“Not on your life!” Tommy laughed. “You’re his best friend. If we let him pick, he’ll pick you. I say we fight for it. I have boxing gloves at home.”

“No way!” Alan squeaked. He’s small and never gets into fights.

“I don’t want to fight either,” I said. I’m no coward but I knew I wouldn’t stand a chance against Tommy. His dad teaches him how to box properly and they have their own punching bag. He would have floored me in the first round.

“Let’s pick straws for it,” I said, but Tommy didn’t want to. He has terrible luck and never wins anything like that.

We argued about it a bit more, until Steve came up with an idea. “I know what to do,” he said, opening his school bag. He tore the two middle sheets of paper out of an exercise book and, using his ruler, carefully cut them into small pieces, each one roughly the same size as the ticket. Then he got his empty lunch box and dumped the paper inside.

“Here’s how it works,” he said, holding up the second ticket. “I put this in, put the top on and shake it about, OK?” We nodded. “You stand side by side and I’ll throw the bits of paper over your heads. Whoever gets the ticket wins. Me and the winner will give the other two their money back when we can afford it. Is that fair enough, or does somebody have a better idea?”

“Sounds good to me,” I said.

“I don’t know,” Alan grumbled. “I’m the youngest. I’m not able to jump as high as—”

“Quit yapping,” Tommy said. “I’m the smallest, and I don’t mind. Besides, the ticket might come out on the bottom of the pile, float down low and be in just the right place for the shortest person.”

“All right,” Alan said. “But no shoving.”

“Agreed,” I said. “No rough stuff.”

“Agreed,” Tommy nodded.

Steve put the top on the box and gave it a good long shake. “Get ready,” he told us.

We stood back from Steve and lined up in a row. Tommy and Alan were side by side, but I kept out of the way so I’d have room to swing both arms.

“OK,” Steve said. “I’ll throw everything in the air on the count of three. All set?” We nodded. “One,” Steve said, and I saw Alan wiping sweat from around his eyes. “Two,” Steve said, and Tommy’s fingers twitched. “Three!” Steve yelled, jerked off the lid and tossed the paper high up into the air.

A breeze came along and blew the bits of paper straight at us. Tommy and Alan started yelling and grabbing wildly. It was impossible to see the ticket in among the scraps of paper.

I was about to start grabbing, when all of a sudden I got an urge to do something strange. It sounded crazy, but I’ve always believed in following an urge or a hunch.

So what I did was, I shut my eyes, stuck out my hands like a blind man, and waited for something magical to happen.

As I’m sure you know, usually when you try something you’ve seen in a movie, it doesn’t work. Like if you try doing a wheelie with your bike, or making your skateboard jump up in the air. But every once in a while, when you least expect it, something clicks.

For a second I felt paper blowing by my hands. I was going to grab at them but something told me it wasn’t time. Then, a second later, a voice inside me yelled, “NOW!”

I shut my hands really fast.

The wind died down and the pieces of paper drifted to the ground. I opened my eyes and saw Alan and Tommy down on their knees, searching for the ticket.

“It’s not here!” Tommy said.

“I can’t find it anywhere!” Alan shouted.

They stopped searching and looked up at me. I hadn’t moved. I was standing still, my hands shut tight.

“What’s in your hands, Darren?” Steve asked softly.

I stared at him, unable to answer. It was like I was in a dream, where I couldn’t move or speak.

“He doesn’t have it,” Tommy said. “He can’t have. He had his eyes shut.”

“Maybe so,” Steve said, “but there’s something in those fists of his.”

“Open them,” Alan said, giving me a shove. “Let’s see what you’re hiding.”

I looked at Alan, then Tommy, then Steve. And then, very slowly, I opened my right-hand fist.

There was nothing there.

My heart and stomach dropped. Alan smiled and Tommy started looking down at the ground again, trying to find the missing ticket.

“What about the other hand?” Steve asked.

I gazed down at my left-hand fist. I’d almost forgotten about that one! Slowly, even slower than first time, I opened it.

There was a piece of green paper smack-dab in the middle of my hand, but it was lying face down, and since there was nothing on its back, I had to turn it over, just to be sure. And there it was, in red and blue letters, the magical name:

CIRQUE DU FREAK.

I had it. The ticket was mine. I was going to the freak show with Steve. “YEEEEEEESSSSSSSSSSSSS!!!!” I screamed, and punched the air with my fist. I’d won!

CHAPTER SEVEN

THE TICKETS were for the Saturday show, which was just as well, since it gave me a chance to talk to my parents and ask if I could stay over at Steve’s Saturday night.

I didn’t tell them about the freak show, because I knew they would say no if they knew about it. I felt bad about not telling the whole truth, but at the same time, I hadn’t really told a lie: all I’d done was keep my mouth shut.

Saturday couldn’t go quickly enough for me. I tried keeping busy, because that’s how you make time pass without noticing, but I kept thinking about the Cirque Du Freak and wishing it was time to go. I was quite grumpy, which was odd for me on a Saturday, and Mum was glad to see the back of me when it was time to go to Steve’s.

Annie knew I was going to the freak show and asked me to bring her back something, a photo if possible, but I told her cameras weren’t allowed (it said so on the ticket) and I didn’t have enough money for a T-shirt. I told her I’d buy her a badge if they had them, or a poster, but she’d have to keep it hidden and not tell Mum and Dad where she’d got it if they found it.

Dad dropped me off at Steve’s at six o’clock. He asked what time I wanted to be collected in the morning. I told him midday if that was OK.

“Don’t watch horror movies, OK?” he said before he left. “I don’t want you coming home with nightmares.”

“Oh, Dad!” I groaned. “Everyone in my class watches horror movies.”

“Listen,” he said, “I don’t mind an old Vincent Price film, or one of the less scary Dracula movies, but none of these nasty new ones, OK?”

“OK,” I promised.

“Good man,” he said, and drove off.

I hurried up to the house and rang the bell four times, which was my secret signal to Steve. He must have been standing right inside, because he opened the door straightaway and dragged me in.

“About time,” he growled, then pointed to the stairs. “See that hill?” he asked, speaking like a soldier in a war film.

“Yes, sir,” I said, snapping my heels together.

“We have to take it by dawn.”

“Are we using rifles or machine guns, sir?” I asked.

“Are you mad?” he barked. “We’d never be able to carry a machine gun through all that mud.” He nodded at the carpet.

“Rifles it is, sir,” I agreed.

“And if we’re taken,” he warned me, “save the last bullet for yourself.”

We started up the stairs like a couple of soldiers, firing imaginary guns at imaginary foes. It was childish, but great fun. Steve ‘lost’ a leg on the way and I had to help him to the top. “You may have taken my leg,” he shouted from the landing, “and you may take my life, but you’ll never take my country!”

It was a stirring speech. At least, it stirred Mrs Leonard, who came through from the downstairs living room to see what the racket was. She smiled when she saw me and asked if I wanted anything to eat or drink. I didn’t. Steve said he’d like some caviar and champagne, but it wasn’t funny the way he said it, and I didn’t laugh.

Steve doesn’t get on with his mum. He lives alone with her – his dad left when Steve was very young – and they’re always arguing and shouting. I don’t know why. I’ve never asked him. There are certain things you don’t discuss with your friends if you’re boys. Girls can talk about stuff like that, but if you’re a boy you have to talk about computers, football, war and so on. Parents aren’t cool.

“How will we sneak out tonight?” I asked in a whisper as Steve’s mum went back into the living room.

“It’s OK,” Steve said. “She’s going out.” He often called her she instead of Mum. “She’ll think we’re in bed when she gets back.”

“What if she checks?”

Steve laughed nastily. “Enter my room without being asked? She wouldn’t dare.”

I didn’t like Steve when he talked like that, but I said nothing in case he went into one of his moods. I didn’t want to do anything that might spoil the show.