Полная версия

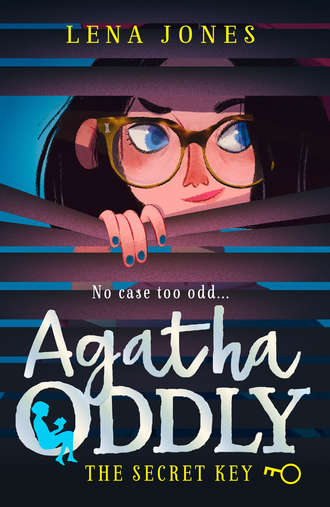

The Secret Key

He sounds strained. ‘Erm … not.’

‘All right. But you can still help out with something.’

He brightens. ‘What?’

‘On the woman’s wrist, there was a symbol.’

‘A symbol?’

‘Well, a tattoo. I feel like I’ve seen it somewhere before. I need you to find out what it means.’

‘Sure. What did it look like?’

‘I’ll draw it for you.’ I take my fountain pen and draw from memory the eye-and-key tattoo. ‘I was thinking you could check Masonic symbols first, then alchemical, witchcraft …’

‘OK … I’ll scan it into my laptop and run some image-recognition algorithms to—’

‘Yes, yes. Whatever you have to do.’ I should have mentioned before that Liam is a computer genius. When he gets going about techy stuff, I have no idea quite when he’ll stop.

‘Right, I’d better be off then.’

Liam shrugs. ‘You’re going to be in so much trouble if you’re caught, Aggie … Oh, wait! Hang on a sec.’ He reaches into his bag and pulls out a black box, which he holds up to my mouth. ‘At least if I’m here I can cover for you. Say “here”.’

‘Why?’

‘Just do it.’

‘Here.’ I repeat into the box.

He takes the box away and presses a button.

Here, says the box in my voice.

‘I can hide this at the back of the class and remote control it with my phone when they call the register.’

‘Can’t you just say “here” for me?’

‘Do you think my impersonation of you is that good?’ Liam raises an eyebrow.

‘Point taken. Now, I really need to go!’

‘How are you going to get out? They’ve already locked the gates.’

‘Well, it’s a Thursday, isn’t it?’

‘Yeah, so?’ He looks blank.

I smile.

‘Don’t worry, I’ll tell you later.’

Getting out of form class is as easy as excusing myself to use the loo. From there on, things become complicated. When I woke this morning, my brain felt grey and heavy, like an old wash rag that needed wringing out. But now I’m full of energy, which is good – I’ll need to be as awake as possible to escape St Regis.

I take the stairs down to the assembly hall, my footsteps echoing on the stone floor. I have three minutes before the bell goes and everyone rushes out of class. I make it past the biology labs, alongside the headmaster’s office and into the Great Hall with its polished maple floor. This is where we have assemblies, and where we sit exams. Even though the hall is empty, I feel watched by an invisible presence, and not just from the dusty frames of St Regis’ past alumni. I shiver and hurry on.

Creeping quickly over to the back doors, I hurry out on to the playing fields. I take off my red beret, crouch down, and start to run under the windows of the maths department, where students are still in form class. From an open window, I can hear one of Dr Hargrave’s sermons on innocence and obedience.

‘The rules are there to protect students from themselves. Stay within the rules, children, and you have nothing to fear …’

‘… and nothing to gain,’ I mutter, forging on.

At the end of the block, I stop and peer round the corner. The entire school is ringed by a three-metre-high wire fence, impenetrable with the tools I have on me (strawberry-flavoured eraser, 2HB pencil). The only way out is in disguise, and I’m looking right at one – between the sports teacher’s hut and the door to the kitchens stand the half-dozen wheelie bins that are collected by the council twice a week.

I know Mr Harrison, the PE teacher, will be having a cigarette in the privacy of his hut before the first class arrives to collect their hockey sticks and basketballs. He’s a creature of habit (full-tar, slim filter), and I’m relying on that. Smoke signals from the window support my hunch. Coast clear, I creep across the open ground to the bins and quickly look inside each of them in turn. All of them are full to the brim with tied-up rubbish sacks. What a pain.

Quickly, making as little noise as possible, I empty one bin, stashing the sacks in the space between the hut and the back wall of the school. I take off Mum’s scarf and put it in my pocket – I don’t want it getting dirty. For a second I hear a noise from the hut and freeze, but nobody comes out. The bin is empty. I peer in. There is a thin, brownish slime at the bottom, and a strong smell of rotten fruit. I sigh. With a last look at my polished shoes and my lint-brushed skirt, I start to climb in.

As I do, there’s a sound of unlocking from the kitchen door. Quickly, I crouch down in the foul-smelling bin and shut the lid. I’m in warm, smelly darkness, but I can hear well enough.

‘Oi, Charlie! You got anything else that needs chucking? I’m gonna put the bins out.’ It’s one of the kitchen workers.

‘Yeah,’ replied another voice, ‘take these peelings.’

There are muffled noises and footsteps coming closer. I close my eyes and hope he doesn’t pick the bin I’m in. A moment later, light floods in. I look up. A young, stubbled face peers at me, looking startled.

‘Oh, hey, David!’ I say cheerfully.

‘Again, Agatha?’ He does not seem thrilled to see me.

‘Look, David—’

‘Dave.’

‘Dave, this is very important.’

‘It was very important last time. I could lose my job!’ He speaks in an urgent whisper.

‘Look, this is the last time, I swear. Never again.’

He stares at me, unspeaking, then back to the kitchen, then at me again.

‘Never again,’ he says. ‘And if you get caught, I didn’t know you were in there, OK?’

‘Sure.’

He dumps the bag of potato peelings on my head and slams the bin shut. If I weren’t in hiding, I might have sworn. I spend another five minutes in cramped confinement, trying to shift the soggy bin bag from my head without making a sound. I hear Dave taking the bins around me, one by one, to the gates. I’m sure he’s leaving mine until last, prolonging my discomfort. Finally, I feel my centre of gravity shift sideways, and we begin the bumpy ride to the bin depot. With a last thud, my journey is complete.

I wait a moment until Dave has time to go back inside the gates. A dribble of cold juice has escaped the bin bag and trickles down my neck. A shiver runs up my spine. With the bag on top of me, it’s impossible to peek out and see if the coast is clear. Instead, deciding I can’t put it off any longer, I spring out.

The bin depot is outside the school grounds, next to the H83 bus stop. A small old man flattens himself against the shelter in shock.

‘Sorry!’ I leap out of the bin and make off down the road at speed, slinging my satchel over my shoulder.

‘Stop!’ he yells ‘You … you criminal!’

I shout over my shoulder, feeling the need to correct him.

‘I’m not a criminal – I’m a detective!’

Away from the bus stop, I take out my notebook. Where to start? Hmm. First I should take another look at the crime scene – the longer I leave it, the more it’ll be contaminated with litter from passing tourists. Time is of the essence. From Hyde Park I can then walk to the Royal Geographical Society – the base for Professor D’Oliveira – on Kensington Gore. My body is tingling, almost light-headed. What is this feeling, I wonder? Then I realise –

Adrenaline! I feel alive!

As I hurry back towards Hyde Park, I have to skirt round crowds of tourists on every corner, stopping to have their pictures taken beside red phone boxes. When I get to the park, I use my best subterfuge to keep out of sight of Dad’s gardeners, most of whom will know me if they spot me.

I cross the grass, rather than taking the main paths, hiding behind trees and shrubs, and only moving when I’m sure the coast is clear. As I reach the scene of the hit-and-run, I take a quick look around. There are plenty of people, but there aren’t any abandoned wheelbarrows or lawnmowers to suggest a gardener is nearby.

I’m hoping to spot a clue to the biker’s identity, when I see something glinting under a prickly shrub and, with a quick look down at my already filthy skirt, get down on my knees and crawl towards it. At that moment, I hear Dad’s voice, sounding sombre and far too close.

‘It’s very strange; I’ve never seen anything like it before. I’m wondering if it’s connected to the water mains. Anyway, I’ve taken some samples.’

I don’t hear his companion’s reply, but two pairs of feet stop in front of my hiding-place.

‘This mahonia has got far too leggy.’ It’s Dad’s voice. ‘We should look at that in the spring.’ Again, his companion makes a quiet response. I concentrate on staying still. Then the voices move away, and I realise I’ve been holding my breath.

They haven’t seen me.

I look at the object I crawled under the bush for, but it’s just a chocolate wrapper. I crawl out, feeling stupid, and hoping nobody spotted me.

‘Agatha!’

Crud.

Lucy, Dad’s deputy gardener who looks after the plant nurseries, has spotted me. Luckily, Lucy always assumes the best of me.

‘How’re you doing?’ She blows a lock of hair out of her eye.

‘Good, thanks. Busy.’

‘Yeah, tell me about it. I’ve got weeds coming out of my ears!’ Lucy grins. ‘Shouldn’t you be in school?’ she asks, the first doubt creeping in.

‘Free period,’ I lie. Lucy deserves better, but I can’t risk her telling Dad.

She nods, as though this should have been obvious. ‘Oh, I have something for you.’ She fishes in her pocket and draws out a pencil. ‘One for your collection.’

‘Thank you – where did you find it?’

She shrugs. ‘Just down the path here. Anyway, I’d better get on.’ She waves her border fork and heads back to work.

I take a seat for a moment on the bench. I look at the pencil a while before dropping it into my lap as though I’ve been burnt. A pencil, lying on the path near where the hit-and-run took place? Perhaps it belonged to the professor!

Careful not to touch the pencil any more, I take a pair of tweezers from my satchel and use them to move the pen to a clear bag. Embossed in gold on the side are the initials ‘A. A’. Not Dorothy D’Oliveira’s pencil, it would seem. The fingerprints on the outside of the pencil might have been wiped away by Lucy and me handling it, but there could still be some on the grip. Perhaps the pencil was dropped by a tourist passing through the park, but at this stage I have to take it seriously.

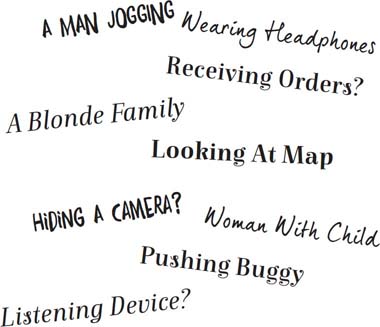

Standing, I dust myself down. I pause – I have the sensation that someone is watching me. I look around and see –

None of them seem to be looking directly at me, but good spies are clever. They’re able to hide what they’re up to.

I inspect my clothing quickly. The knees of my navy tights are green, as are the elbows of my matching blazer. Far worse, there is a rip in my skirt. I must have caught it on the shrub when I crawled under it. This is my only school skirt and I wonder if I’ll be able to mend it without Dad discovering.

But for now, I have more important things to think about – time to visit the Royal Geographical Society (RGS).

It takes me no time at all to get from the park to Kensington Gore. The exterior of the RGS is a bit disappointing – from the name you might expect a beautiful structure, like the white-and-redbrick façade of the Science Museum on the nearby Exhibition Road. The RGS entrance is a newer addition, made from floor-to-ceiling glass. It looks like it might take off in a strong gust of wind.

I walk the short distance from the pavement to the glass entrance. Inside, a man in a smart suit sits behind the reception desk. He looks me up and down – slowly, and with a raised eyebrow.

‘Not looking your usual well-coiffed self today, Agatha,’ he observes.

I pull a face and smooth my bob. ‘Sorry, Emile. Difficult day. I was hoping to speak to you about this …’ I draw the business card from my pocket.

‘Agatha, we’ve been over this,’ he interrupts, shaking his head. I feel quite sorry for Emile – he’s always having to turn down my requests, and I can tell it doesn’t suit him. ‘I can’t give you a lifetime membership to the Society.’

‘Oh, no – that’s not why I’m here.’

‘It’s not? You mean … you have a query – an actual query – that I might be able to help you with?’ He brightens.

I nod.

‘Oh, good.’ He smiles. ‘I have to say, I was surprised that you weren’t wearing some disguise or another. Like that dirty jumpsuit!’

Ah yes – the time I pretended to be a plumber. ‘Well, anyway …’ I change the subject. ‘If you could take a look at this business card – it belongs to one of your members.’ I place the card on the desk, and he inspects it.

‘Professor D’Oliveira. Why are you enquiring about her?’ He narrows his eyes. ‘Is this one of your detective games?’

‘I do not play games, Emile. I conduct investigations.’

‘Right … Is this one of your investigations?’

I pretend not to notice the sarcasm. I like Emile; it’s just a shame he doesn’t always take me seriously. ‘Possibly … I mean, do you know Professor D’Oliveira?’

‘Of course. She spends a lot of time here – she’s a highly regarded member of the Society.’

‘Good.’ I take out my notebook. ‘Then perhaps you could tell me more about her.’

‘Why?’

‘Sorry?’

‘Why are you asking this?’

I hesitate. It’s hard to know how much to tell. I didn’t want to give any information about the hit-and-run if the Society don’t already know.

‘I met her in Hyde Park, earlier today,’ I say. This isn’t entirely a lie – I did meet her – she had smiled at me, after all. I think quickly and add, ‘and I thought she might make an interesting subject for our school newspaper.’

He smiles. ‘I’m sure she would. I can arrange to make an appointment for you to interview her – only, I don’t think she’s been in today, but let me call her assistant.’ He reaches for the phone.

‘Oh – don’t worry about that for now,’ I say quickly. ‘Perhaps I might have access to the Society’s archives today to check out some facts?’

‘That might be a problem. I don’t think you’ve filled in an application form for access to the Foyle Reading Room?’

I shake my head. ‘Can I do that now?’

‘I’m afraid, for under-sixteens, we would need parental consent.’

‘Really, Emile? Is there nothing you can do?’

‘Well … I suppose I could put in a call to your school – obtain their permission, as it’s for the school newspaper.’

‘Oh! No, that’s all right. I’ll leave it for now. Thanks anyway.’

‘Sorry not to be more help. Do give me a call tomorrow – Professor D’Oliveira often has meetings, so we can sort out that interview soon.’

‘Yeah, thanks, Emile.’

He calls to my back – ‘Agatha!’

I turn with renewed hope, ready to be as charming and grateful as required. ‘Yes?’

‘Did you realise you have a twig attached to your hair?’

‘Ah … no.’

I remove the twig and carry it outside. It’s hot after the air-conditioning, and I’m just pondering where to go from here when suddenly a hand covers my mouth from behind. I’m yanked backwards, out of sight of the foyer building with my arm pinned behind me. A male voice mutters in my ear –

‘You really are a meddling little girl, aren’t you?’

Strangely, I feel a moment of relief that I hadn’t been imagining it – I was being watched back in the park!

But relief gives way to panic. I struggle, but can’t escape the tight grip. Thinking back to self-defence manuals I’ve read, I scrape my heel up his shin and stamp hard on his foot. He grunts in pain but doesn’t loosen his hold.

‘You’re a regular little snooper, Agatha Oddlow.’ His breath is warm and wet on my cheek. He smells of whisky and Chanel Bleu aftershave. A man with expensive tastes.

‘Are you afraid?’ he whispers.

I shake my head as well as I can.

‘Well, you should be – and if you aren’t afraid for yourself, how about that father of yours? What if he had an accident? Be a shame for you to wind up an orphan, wouldn’t it?’

I try not to react – how does he know my name, and what does he know about Dad? How does he know my mum isn’t alive any more?

‘Where would you live if something should happen to him? That little cottage goes with the head gardener’s job, doesn’t it?’

I try to calm my breathing, and focus on his accent. It’s Scottish, that much is obvious. I think back to the tapes I’d listened to in the library – Accents of The British Isles – spending hours with headphones, playing the voices over and over, until I was confident of recognising them all.

Edinburgh – No.

The Borders – No.

Fife – No.

It comes to me – the man is from Glasgow!

This small victory does nothing to help my situation. A shiver works its way down my back. My breathing – already awkward due to the hand across my face – becomes laboured, and I can hear the blood pounding in my ears, like ocean waves. He leans in again. ‘You didn’t see anything this morning in Hyde Park – you understand me? Nothing.’

A rag is clamped over my mouth, and I smell something like petrol fumes. Darkness starts to pull me under. Sight leaves me, then sound, then touch. The last thing that lingers is the chemical smell.

Then nothing.

Darkness.

There is a tiny light, far off and I move towards it, but moving hurts. I’m not sure what is hurting – I don’t have a body yet. Slowly the light grows, white in the darkness. I remember my body – legs and torso, arms and head. Ah yes, my head – that’s where it hurts. I must have fallen. I can hear voices. Where is the man who attacked me?

‘What’s wrong with her?’

‘Mum, is she going to die?’

‘Has anybody called an ambulance?’

I lie there, breathing deeply for a while, wishing for silence so that I can think straight. Another voice, gentle but firm, cuts through the rest.

‘Excuse me, please. I’m a doctor.’

Then something soft is placed under my head. The white light fades and turns into a face – the face of a man.

‘Hello. Are you all right?’

‘Mmf,’ I say.

‘Let me help you up.’

The man takes my arm gently and helps me into a sitting position against the wall. The crowd moves away. As my vision clears, I look at the man who is crouching to help me. His hair is white, though he can’t be much older than Dad. He has high cheekbones and very pale blue eyes. One hand grips a black malacca cane. His suit is white linen, with a silver watch chain between waistcoat pockets. His face is angelic.

‘Are you all right?’ he asks again.

‘Yes.’ I frown. ‘I, uh … I’m fine. I just slipped,’ I lie. My voice is hoarse – I haven’t had a drink in ages, and my throat is dry and gritty. I look round, trying to pick out anyone who might have been my attacker. ‘Are you a doctor?’ I ask the man.

‘Not practising. In my youth, I studied medicine at La Sorbonne.’

‘Oh … Paris.’ I say rather dumbly. My brain is full of fog.

He smiles indulgently. ‘Now, do you feel up to standing?’ He stands carefully, using the cane as support, and offers his hand. I take it, and manage to get to my feet, though my legs still feel wobbly. He’s wearing cologne, but this time I don’t recognise the brand. He’s so elegant, so very well dressed, that I can hardly believe I’m awake at all. I feel so foolish standing in front of him – with a torn skirt and messed-up hair – that I can’t think of anything to say.

‘Are you all right?’ He asks again.

‘Oh, yes … thank you.’

‘Not at all. Now, it’s a hot day – I think you should get yourself a cold drink.’ He takes a coin from his pocket and presses it into my palm. ‘Doctor’s orders.’

Smiling, he bows his head once and sets off down the street, malacca cane tapping the pavement. I feel a pang as he goes – as if an old friend has visited, but can’t stay.

Dazed, I find my way across the street to the nearest pub, the Sawyers Arms. At least I’m not far from home. The inside of the pub is cool and dark, though the barman looks less than pleased to see me. Children aren’t usually allowed in London pubs unaccompanied, but I’m desperate. I want to look for evidence outside the RGS, to track my attacker down. But I’m too tired, too thirsty.

‘Can I have a glass of water, please?’

‘We don’t serve kids,’ he says.

‘Actually, under article three of the Mandatory Licensing Act, you’re obliged to ensure that free tap water is provided on request to customers where it is reasonably available.’

A man sitting by the bar chuckles, but the barman only scowls more.

‘On request to customers,’ he says.

‘Oh, let her have a drink, Stan.’ The man on the stool says. ‘It’s as hot as brimstone out there.’

The barman grunts.

‘Only if she buys something.’

‘I’ll have a packet of peanuts then,’ I chip in.

The barman slouches to reach a pack and throws it in my direction. He gets a glass and picks up the nozzle, which dispenses fizzy drinks and water. But, when he presses the button, nothing comes out. He shakes the nozzle and tries again, but only a dribble appears.

‘Damn thing … you’ll have to have bottled.’

I sigh and hand over the money, too tired to question the charade.

I leave the pub, blinking in the sun’s glare off the pavement. The road is so hot that the tar is melting – I can smell it. The air shimmers. My legs still feel shaky, but I have no money left to get a bus. I tell myself that I’m nearly home – all I have to do is get through Hyde Park without Dad spotting me.

It’s weirdly quiet as I walk past the townhouses on Kensington Road. The air is thick with car fumes, and no breeze stirs. Far off, I can hear the siren of a fire engine. There is the usual row of tourist coaches opposite the park, engines idling to keep their air-conditioning going. At Soapy Suds, the carwash that cleans the Jags and Bentleys of Kensington, a man in a suit is arguing loudly with the attendant.

‘Whaddya mean, you’re not washing cars? Can’t you read your own sign?’

Hyde Park is looking lush, even after weeks of heat – the lawns are emerald green, the flowerbeds blooming. Still, it seems too quiet for a summer’s day in central London – just the occasional dog walker idling their way along a path. Have I missed something while making my investigations? Is everyone indoors, watching a major sporting event, perhaps? An ice-cream van drives past, blinds pulled on the serving window, chimes switched off.

I try to make sense of it, to shift my brain into puzzle-solving mode, but the same two words keep repeating in front of me, like a flashing warning sign –

TOO QUIET

I’m walking over the lawns towards Groundskeeper’s Cottage when I spot two figures in the distance. One of them is Dad, dressed in his overalls. The other man stands next to a large motorbike, and is wearing black biking leathers. His face is obscured by a helmet, but I can tell that the two of them are arguing. Before I know why, I’m running. The words of the man who grabbed me outside the Royal Geographical Society start to run through my head on a loop –

Be a shame for you to wind up an orphan, wouldn’t it?

There is a knot in my stomach, like the end of a rope that links me to Dad.