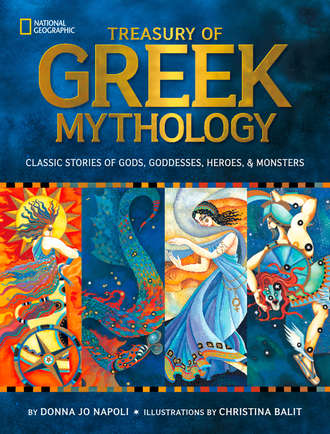

Treasury of Greek Mythology: Classic Stories of Gods, Goddesses, Heroes & Monsters

Полная версия

Treasury of Greek Mythology: Classic Stories of Gods, Goddesses, Heroes & Monsters

Язык: Английский

Год издания: 2019

Добавлена:

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента

Купить и скачать всю книгу