Полная версия

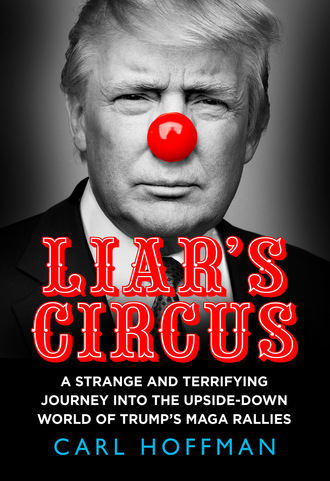

Liar’s Circus

Over three years of Trump’s presidency so many of those values became challenged. Neo-Nazis were defended, dictators befriended, immigrants persecuted, trusted institutions undermined, experts and scientists shunned (with deadly consequences when a crisis finally arrived), truth subverted, national unity gleefully fractured. Americans by the millions supported a politician whose morals and vision I didn’t recognize. My city came back to life, but I wasn’t close friends with a single Trump supporter and never encountered them in my daily rituals, so far as I knew, whether in restaurants, bars, the park, my coffee shop, airports or airplanes or buses or trains. A neighborhood family pizza joint, known for its Ping-Pong tables and booths full of kids and their moms and dads just fifty feet from the drugstore whose shelves I stocked in high school, was invaded by an American terrorist carrying an AR-15 assault weapon. Edgar Maddison Welch fired three shots into the crowded restaurant as he frantically searched for imaginary tunnels in which Hillary Clinton and John Podesta, it was said on the dark corners of the internet, tortured babies and even drank their blood. The fact was, I had no face-to-face interaction with Trump supporters, ever, which was incredible, since sixty-three million Americans had voted for him.

My friend Nick’s comments were typical in my universe. Nick was no tree-hugging Birkenstock wearer. He’d grown up in a tight-knit Catholic family of eight, had paid his own way through the University of Maryland, and risen, through hard work and hours that left me dizzy, to become senior vice president and partner at a global consulting firm, from which he’d been able to retire while still in his fifties. “I guess I’m part of this calcification of the conversation,” he said over drinks one night. “I’ve lost my tolerance. It used to be that if we went out for dinner with conservatives I’d say, ‘We can agree to disagree,’ but I can’t do that anymore. I mean, if you support Trump’s policies that are racist, then you’re a racist. Are you a good person? I don’t know anymore! I realized I can’t do it; I can’t sit there and be tolerant. Their bubble of ignorance and loss of critical thinking just ruins it for me.”

What was happening in this country? My country? I’d spent much of my career traveling the globe to understand cultures that were deeply unfamiliar to me, and suddenly my own felt nearly as foreign as that of the pygmies in the Ituri Rainforest of the Congo. The America of my parents appeared gone. Who were these Trump supporters, this mythical Trump base, and why were they so fervent about a man who stood counter to seemingly every cultural, ethical, social, moral, and political value of my childhood? The ranks of the MAGA faithful included not just that base of non-college-degreed white men, but also men and women with deep educations and power in the GOP; people like Mitch McConnell. So strong was Trump’s hold over the Republican electorate that it became political suicide for any Republican to challenge Trump. What explained his attraction and his hold on people?

For so many years, when I’d wanted to understand a culture, no matter how remote or potentially dangerous, I threw a few clothes in a bag and headed off. I thought nothing of traveling for days to the remotest of places. What interested me the most in those faraway communities was the gathering together of people where ritual and myths reconstituted identity, where people became whole. Was there an equivalent within the United States to help me understand this new America?

My thinking kept returning to Trump’s rallies. They were legendary and legendarily raucous, opportunities for screaming fans (or so I saw in news clips) to chant LOCK HER UP and boo the press. No other president in history had staged as many, an average of more than one a week since his election, often in places sitting presidents rarely traveled, such as Mississippi and Louisiana. The ticketing process pulled in valuable voter data like a giant Hoover vacuum, of course, but that utilitarian purpose seemed their least important function. From the outside, the rallies appeared to be a new American ritual where the identity of the hundreds of thousands who participated in them was solidified, confirmed. “Rituals reveal values at their deepest level,” writes Monica Wilson, who lived among the Nyakyusa people of Tanzania in the 1950s. They are “the key to an understanding of the essential constitution of human societies.” The vast majority of those big GOP donors and pols who were now entwined around Trump’s fingers had originally disdained him. Why had that change happened? How had he converted them? The rallies, it seemed to me, held the answer. Trump had found influence not through the cultivation of years of relationships, of studied political favors and lever pulling in back rooms, but through an unruly, feral, electric mob—incubated and indoctrinated online—that was made flesh and blood and nourished weekly in a new kind of ritual.

The idea took hold and wouldn’t let go: the rallies were the key to decoding and understanding this phenomenon that had swept my country. If Trumpism could be seen and felt, that place was at his rallies, in the arenas that brought together his fabled base into concentrated form. And if so, then it was someplace I could travel to just as surely as a village in the swamps of New Guinea or the huts of nomads in the rain forests of Borneo. “For I was constantly aware of the thudding of ritual drums in the vicinity of my camp,” writes the anthropologist Victor Turner. “Eventually, I was forced to recognized that if I wanted to know what even a segment of Ndembu culture was really about, I would have to overcome my prejudice … and start to investigate it.”

If I was drawn to the rituals of indigenous people, why wasn’t I attracted to the rituals of my own countrymen and women? If I could endure extreme heat and mosquitoes to live with the formerly violent, head-hunting Asmat eating sago worms, why couldn’t I live with the Trumpians? If I could dress in a shalwar kameez and a keffiyeh and ride a bus unchallenged through the Salang Pass of Afghanistan in the middle of a raging war, why couldn’t I go where journalists were vilified in my own country?

The answer was simple: I needed to overcome my prejudice and journey into the heart of darkness that was my own nation. I would get to know, or try to, the most passionate of Trump fans. Live with them. Eat with them. See if I could pierce—and understand—their world.

3.

YOU MUST LOVE JESUS MORE THAN YOUR OWN LIFE

Like Snowden, Frazer, Thompson, and Thom, I pulled into Minneapolis the day before the rally and headed straight to the Target Center, some thirty hours before showtime. I didn’t know what to expect. Crowds? Demonstrators? New revelations were coming out daily concerning the president’s embrace of conspiracy theories about Ukraine and his subsequent effort to block congressionally approved military aid. There was talk of impeachment in D.C. The Democratic mayor of Minneapolis was threatening to withhold crucial security forces and first responders unless the Trump campaign reimbursed the city, and he’d forbidden the wearing of uniforms by police attending the rally as spectators. Indeed, it was hard to remember the days when Minnesota had once been a crucible of left-wing populism, home to farmer’s cooperatives that had spawned the Minnesota Farmer–Labor Party, which had dominated state politics in the twenties and thirties. Eugene Debs, the socialist and founder of the Industrial Workers of the World, won 6 percent of the popular vote in the 1912 presidential election, and twenty-seven thousand of those votes had been in two counties in northern, rural Minnesota. My mother’s relatives, a crowd of great-aunts and uncles and grandparents who remained on farms in adjacent North Dakota when my mother came east as a little girl, had been staunch Democrats. George McGovern hailed from South Dakota and Fritz Mondale from Minnesota, and Minnesota was the one and only state Mondale kept out of Reagan’s hands in 1984. All of which was why the 2016 election results had been so stunning: Hillary Clinton won the state by a mere 44,765 votes. Lake Wobegone country was now a sea of red, just like the rest of rural America, and the Trump campaign wanted not just to win Minnesota but to stake its MAGA flags in the heart of downtown Minneapolis, home to the country’s largest community of Somali Americans and the congressional district of Democratic representative Ilhan Omar.

Downtown at the arena, though, all appeared quiet. As workers began erecting chain-link fencing around the perimeter, I circled it and noticed a small crowd overhead in a glass-enclosed skyway leading to the arena. I had not come prepared for an overnight hangout, and I didn’t understand yet what was happening in front of me; my plan was simply to reconnoiter and return before dawn the next morning. I hadn’t yet met Snowden and the gang. I found the skyway, snapped a photo of myself with Hardings’s cardboard Donald just for kicks, and left.

Getting to Minneapolis had taken me a week, days of rambling some sixteen hundred miles northwest from Washington, D.C., along interstates and blue highways. I had always hated the term “flyover country,” which wasn’t just condescending but ignorant, and though I hadn’t written a whole lot about it, rural America felt familiar to me. I had been to every state in the U.S. except South Dakota, including Hawaii and Alaska. I had been deep underground in an Appalachian longwall coal mine; I had spent days on an American deep-water oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico; I’d even visited U.S. aircraft carriers at sea, as sure a piece of American real estate as any other. The year I turned eighteen I’d lived for eight months in Colorado and spent occasional weekends with my roommate at his family farm in Goodland, Kansas. For years when my children were young, we had driven to my in-laws in New Mexico every summer. A magazine story I’d written about the majesty of eastern Montana had even been turned into a slogan advertising the state.

Middle America had changed over the years, though. In January 2009, the very week of Barack Obama’s inauguration, I’d taken a dispiriting trip on a Greyhound bus from Los Angeles to D.C. The final leg of a fifty-thousand-mile journey around the world on the most dangerous buses, boats, trains, and planes, it was by far the worst, most depressing segment of that epic trip. Even on broken African trains or on a crowded Indonesian ferry, I was surrounded by friendly, smiling, optimistic people eager to talk, curious about the United States. Delicious, home-cooked food hawked by vendors was plentiful and cheap. Most everyone carried shiny, new cell phones, and in many countries—India and Indonesia and Mongolia, for instance—the pace of new construction was frenetic. The world felt bursting and eager. But witnessed from the lurching Greyhound—the only conveyance on that dangerous journey that broke down so completely it had to be abandoned—the United States seemed to be coming apart; it looked broken, cracked, fading, full of abandoned towns and empty malls. My fellow passengers were no better: they carried their belongings in black plastic trash bags, ate at “Greyhound Steakhouses” (McDonald’s), and that trip was the only time in fifty thousand miles when a stranger refused to watch my bag for a moment. The decrepitude I’d witnessed on that journey was the fertile petri dish for the rise of Donald Trump.

Just nine months later, in October 2009, the Great Recession ended, and since then the United States had seen 124 consecutive months of expansion—most of it under Barack Obama—the longest in history. As I drove to my first Trump rally in Minnesota from my home in D.C., taking a week to ramble through western Maryland and West Virginia into Ohio, I could see it: the country—at least on a purely superficial level—felt brighter, more affluent, less despairing.

I spent a night in Celina, Ohio, the seat of Mercer County, which went for Trump by a whopping 81 percent, more than any other county in the state. Like so many of America’s small towns, Celina was two places—the new, bustling strip right off the interstate, of fast-food joints and chain motels anchored by a giant Walmart surrounded by acres of parking lot—and a quiet, old downtown, full of abandoned storefronts and once-stately stone or brick structures. Celina had a plethora of bars, though, and as the sun dropped and a few neon signs winked on, I stopped in at the Steak and Ale.

This idea that Trump territory was some unrecognizable, alien place simply wasn’t true, I thought, looking over a fantastic list of five hundred beers as a college football game played silently on the tube over the long wooden bar and Nina Simone ached through the speakers. In fact, over the course of the next several months, I was struck repeatedly by how familiar it was. It looked the same everywhere, from Ohio to Minnesota to Mississippi to the suburbs of the bluest of blue cities like D.C., places like Manassas, Virginia, a giant, vast suburb of increasing homogeneity. There were exceptions, always, but so much of America outside of its urban centers consisted of the same stores, restaurants, hotels, motels, car repair joints, gas stations; the same music on the radio and the same shows on TV or the internet and the same clothing. I was just beginning to understand this was one small piece of the great structural issues that had led to Trump. In the opening of my travels in Celina, I hadn’t yet identified it, an idea that only took shape gradually, the more I saw and the more I listened.

“Eh, things here are good and they’re bad,” Justin the bartender said, pouring me a pint of Moeller Brew Barn’s Wally Post Red Ale and taking my order for the filet mignon, which turned out to be as tender as a piece of chocolate cake. He was thirty-six, had black studs in both ears, black rectangular glasses, a wispy beard, and wouldn’t have stood out in my hipster D.C. coffee shop.

“I grew up here and we’ve had a real bad drug problem,” he said. “Opioids. Lots of young people have passed, people I went to school with.”

“What do you think about the president?”

“Well, I voted for him, though I have a lot of mixed feelings about a lot of things. Like the border. Why let in any refugees if you’re not going to close the border? It should be closed. Don’t let anyone in. He wants to build the wall and they’re holding him back, just so the next one who gets elected can do it and be the big hero.” I wasn’t sure what he meant about “the next one,” when he added, “And right now you got the U.N. guarding the border.”

“Wait,” I said. “That’s not true. The U.N. has no jurisdiction over the U.S. border. At all.”

He smiled and shook his head. A knowing smile, a little condescending at my naivete. It was the first of dozens of such conversations I’d have in the coming months, conversations that led directly to the most insidious conspiracy theories, a mythical worldview that wasn’t possible to refute or even discuss. The knowing dismissals were not occasional, but constant.

Justin claimed to be Irish and Native American—“I’m half Mescalero Apache, the three hundredth generation of Geronimo,” he said—and “given my heritage I don’t like to open the door to conflict and I just keep it to myself, but there’s a lot of ethnicity around here. Two Mexican restaurants owned by Mexicans and a lot of Marshallese”—Mercer County’s chicken processing plants had drawn one thousand citizens of the Marshall Islands to Celina—“and some things they do are okay and some are not okay. I don’t want their beliefs rubbing off on my children,” he said, as Amy Winehouse kicked in.

As I drove onward through Ohio and Indiana and Illinois, I listened to FM radio, and in the broadcast desert of rural America there was one constant: religious radio. It was everywhere all the time, a stream of invective and partisan “news,” and extreme preaching. We must think, a preacher in Ohio said, “what Christ wants versus what man wants. Jesus is saying we must choose to do what Christ wants rather than what our family wants. A father cannot support his homosexual son. If a daughter is wearing the wrong clothes and a father does not say to his daughter you cannot leave the house with those clothes on, then he’s not being a good father. If we have to choose Christ over family, the answer is Yes. We must carry our own cross. I pray that our attachment to Yes is so strong that we give everything else up.” I changed the station.

I was still trying to process that message—was this preacher really suggesting that disowning our gay sons was good parenting? Was that really what Jesus would have wanted us to do?—when a different preacher on a rival station started talking about “the Tribulation, when one quarter of the world’s population would die.” He mentioned the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse and explained that some people think the Rapture will come first, some the Tribulation. “There is a time when you can’t buy or sell. You’ll be put to death unless you take the mark of the beast, which might even be a computer chip.” There was something about “ints,” which we’d all use to carry out worldwide trade because by then—and “then” seemed pretty soon—there would be “one world currency and one world system and you’ll have the mark of the beast or you will be put to death and starve. At what point would you lose your faith?” the preacher asked. “What would you do if someone said you must deny Jesus Christ or we’ll take your children and they will be abused and starved? Would you maintain your faith?” You must love Jesus more than your own life, he preached, more than your own children. “Some Coptic Christians walked down the streets of Cairo with T-shirts that said, ‘I’m a martyr, take me.’ Isn’t that wonderful if we in the U.S.A. did this?”

It was jarring to hear exaltations of martyrdom on mainstream radio. How was that much different from ISIS or Al Qaida or Taliban suicide bombers, for whom death in service to God was better than life on Earth taking care of their own families? Passing through state after state, I listened to hours of these millenarian, apocalyptic warnings, and it all served as context for the rallies, a warm-up of sorts, an introduction to a deep and wide vein of American evangelical Protestantism. It was the tap root of American culture, dating right back to the Puritans and Plymouth Rock, and it helped pave the way for so many of the conspiracy theories that were the foundation of Trump’s presidency and support. If you believed the Rapture was imminent and were looking for the Mark of the Beast, why not that vaccines caused autism or that the Q Clock was a font of coded messages or that Hillary Clinton raped babies or that the deep state in collusion with the Fake News was trying to stage a coup? I was beginning to get an inkling of the darkness I was journeying toward.

I crossed into Iowa and noticed an island in the middle of the swollen and slow and silvery Mississippi called Sabula, and in the gray chill of late afternoon I crossed a half-mile causeway into a rugged little community that reminded me more of places I’d been in Siberia than America. Duck-hunting blinds made from skiffs, bristling with sticks and camo, sat on trailers in front of tumbledown houses. Fences askew, old cars rusting on blocks. At one end of town stood an abandoned building with silhouettes of pole dancers on the windows and a diner with worn linoleum floors that had the best pork chops and mashed potatoes with gravy I’d ever tasted. From the riverfront I watched a mile-long freight train lumber across a bridge, janking and clanking, its whistle long and lonely.

Though still full from my lunch, I spotted a church barbecue at the local firehouse, so I went in for a second meal. Tables and chairs easily accommodating forty or fifty were set up, though only a dozen or so people, all of them elderly, were there. I filled a paper plate with barbecue and oozing mac and cheese and plunked down across from ninety-four-year-old Florence McCutcheon.

“Oh, I was born twenty miles west of here on a farm,” she said, pulling her pink cardigan a little closer in the chill of the firehouse. “My dad was killed when I was eleven. He had a nice new tractor and went out to plow and it rained and he got stuck and he refused to leave his new tractor out in the rain and it upset on him and killed him. My two brothers were fourteen and sixteen, so they took over and we kept going. But I couldn’t milk a cow! I tried and tried but I couldn’t, so I got out of there.”

What she did was work. “I worked all my life. I went back to work when my daughter was nine months old and I was twenty-two and I worked sixty-six and a half years without a break. I loved it! And,” she said, lifting a foot up to reveal mid-heel black patent leather pumps, “I love my high heels. They’re part of me. I always wear ’em.

“Anyway, that was in 1947 when I went back to work. First, twenty-three years in the garment industry, sewing, and I loved every minute of it and you’d never believe what I quit to do: drive a semi! My husband drove one and I drove one. I didn’t like it, though, and my husband didn’t appreciate my driving. He said I drove too fast. So then I went into abstracting. Got up at four A.M. every day and I did that until I was eighty-seven. I’m going to make it to a hundred and twenty.”

I asked what brought her to the BBQ. “My daughter is seventy-two and she’s the minister of this church and we live together now, so I came with her. I have a prosthetic eye, you know, so I don’t drive anymore.”

How did she feel about Donald Trump?

“I love him. Just love him. For years I was a registered Independent, but now I’m a registered Republican. I just want to shake his hand. Just because he’s rough around the edges and he’s not a politician and I guess that’s what I fell in love with. I don’t know if he’s doing right or wrong, but gosh I’d sure love to meet him.”

McCutcheon’s spirit and energy buoyed me, and I was all set to leave Sabula when I noticed a plain-looking green building with a rusty sign identifying it as the Sabula Miles VFW, “open to the public.” Inside I found a scene from The Deer Hunter. A yellow Formica-topped bar ran along one end of a big, open room floored in more brown linoleum. The walls hung with framed American flags and medals, two slot machines blinked, and over the bar the Green Bay Packers were battling it out with the Dallas Cowboys. Five women with gray hair, cradling cans of beer in insulating foam cozies, sat next to each other on black Naugahyde stools. I found an empty one next to Kevin Lambert, who was drinking bourbon and soda out of a plastic cup. Lambert, the former police chief of Cordova, Illinois, on the other side of the river, was dressed in a black MIA/POW T-shirt and a black baseball cap. I ordered a can of Bud Light in a cozy and settled into another tale of hard knocks and woe: time in the military; a car accident as a young policeman that left two dead and him in a coma for one month and unable to walk for one and a half years. Lambert’s wife left him and he’d lost his job. But he’d clawed his way back and repossessed his badge, only to lose it for the last time after, he said, he dared to arrest the son of the mayor, who was technically Lambert’s boss. “‘I’m just doing my job,’ I told him, but he was on my ass from then on, trying to fire me. I got a lawyer but the writing was on the wall.” (What he didn’t mention—what so many men, especially, didn’t mention in their them-against-the-man stories—was his own responsibility in his fall from grace. In fact, a simple Google search revealed that, not long before his resignation, he’d been discovered “asleep” in his car in a parking lot late at night and then been driven home by a fellow law enforcement officer, which was just a few months after he’d struck a car at 1:00 A.M. and then fled the scene. Nor did he mention the two protective orders signed against him by his former wife and another woman.) Now he slung beers at the VFW part-time, and he was often on one side of the bar or the other. “I like it here. I like to talk and I like to listen,” he said, “and everybody supports everybody else. We don’t talk politics at the bar. I was raised a Democrat, but I like the way Trump stirs things up. I voted for him and I’ll probably do it again.” I remarked that I was surprised the VFW was open to the public, and he said something that stuck with me: “No one joins the VFW anymore. We can’t get ’em in, and if it wasn’t open to the public, it would all just die.”