Полная версия

Liar’s Circus

COPYRIGHT

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

This edition published by HarpercollinsPublishers 2020

FIRST EDITION

Text © Carl Hoffman 2020

Cover layout design ©HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2020

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Carl Hoffman asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

Source ISBN 978-0-00-841597-6

Ebook Edition © October 20 ISBN: 978-0-00841599-0

Version 2020-13-08

DEDICATION

FOR CHARLOTTE

EPIGRAPH

By compromising we could learn how each small demand for our outward acquiescence could lead to the next, and with the gentle persistence of an incoming tide could lap at the walls of just that integrity we were so anxious to preserve.

—CHRISTABEL BIELENBERG, THE PAST IS MYSELF

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

DEDICATION

EPIGRAPH

AUTHOR’S NOTE

PART ONE: HELL

1. THE CROWD LOVES DENSITY

2. ARE YOU A GOOD PERSON?

3. YOU MUST LOVE JESUS MORE THAN YOUR OWN LIFE

4. HE’S HEAVEN-SENT

5. DREAM ON

6. THE PEOPLE AND THE ANTI-PEOPLE

7. THEY EVEN DOWNSIZED WALMART

8. IT’S ALL PSYOPS

9. ORDINARY PEOPLE

10. SHE’D KILL TO WIN

11. THE LEADER WANTS TO SURVIVE

PART TWO: PURGATORY

12. HER PENIS IS SWINGING

13. I’D PICK UP HIS POOP

14. I WOULD FIGHT YOU FOR HIM

15. THAT BLACK WOMAN WAS NOT HERE

16. WE ARE KICKING THEIR ASS

17. THOUSANDS CRIED OUT … SOME FAINTED

18. A SELF-INDUCED IMAGINARY FRENZY

19. THEY GOT FULL OF IDEAS

20. WE HAVE A SOLUTION

21. COERCION. DOMINATION. CONTROL.

PART THREE: PARADISE

22. I WON’T BEND OVER AND LICK THEIR ASS

23. THE Q CLOCK WILL BLOW YOUR MIND

24. SOMEDAY WE’LL GO FOR A HORSEBACK RIDE

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

NOTES

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

OTHER BOOKS BY CARL HOFFMAN

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

AUTHOR’S NOTE

This is a work of nonfiction drawn from approximately three months on the road going to eight rallies in eight states. I drove more than five thousand miles, spent more than 170 hours in line in arena parking lots, and listened to the president, up close and in person, for more than twelve hours. Every quote is true, either transcribed in contemporaneous notes or recorded on my telephone. To capture the absurdist non sequitur nature of so many conversations, I have tried to keep them whole, rather than stitched together, which sometimes makes for long, strange passages. Each quote from the president was checked against transcripts of his speeches. Every name is real. There is nothing fake here.

PART ONE

HELL

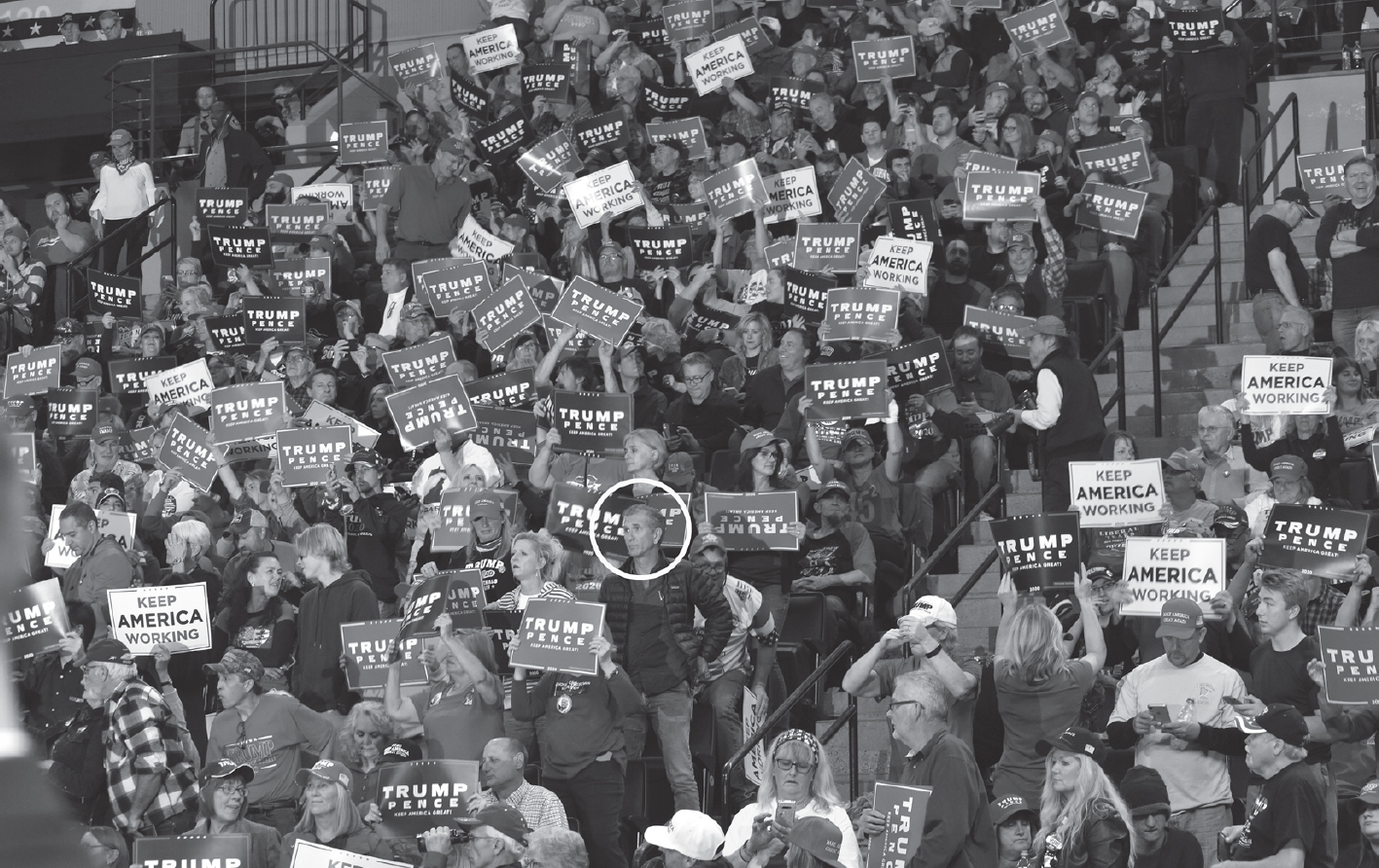

The author (circled) feeling lost and apart at his first rally, in Minneapolis. Dana Ferguson / Forum News Service

1.

THE CROWD LOVES DENSITY

We trickled into Minneapolis by ones and twos, a migratory influx that grew as showtime approached.

In Las Vegas, sixty-nine-year-old Rick Snowden slipped into brown moccasins and loaded a few blue and gray pin-striped suits, a handful of repp ties, and a bottle of Paco Rabanne cologne into his 2001 champagne-colored Jaguar XJR sedan and headed for the airport. The Jag had 195,000 miles on its odometer and RAS—his initials—hand-painted on the front doors. The suits were Snowden’s real signature, though. Sixty million dollars, he liked to say, had passed through his hands over a long career as owner and manager of a slew of strip joints from D.C. to Vegas. He made a point of always looking good—and smelling good—in case he met the president. (He’d had his photo taken with six commanders in chief.) This would be his fifty-sixth Donald Trump rally, and no one had him beat.

In St. Marys, Ohio, where a once-thriving business district had been rendered a ghost town by Walmart and other forces of global capitalism, Rick Frazier and Rich Hardings climbed into Frazier’s SUV and headed north. Frazier, tall, angular, as thin as a two-by-four and as kind as a grandmother, was a sixty-three-year-old retired pipe fitter. With a high school diploma and a union card he’d weathered a nine-month layoff back in the day and several long strikes, and by the time he retired after forty years, he was making $30 an hour, with double time on weekends and triple time on holidays. He had paid vacations, health benefits, and, now, a pension. He had a cat named Frank (after Sinatra) who slept on his chest. He played the guitar and favored the classic southern rock of the Allman Brothers and Lynyrd Skynyrd and had once headlined a band called Sterling Foster (named after a beer sign he’d seen). Frazier was as all-American as Budweiser before it was bought by the Belgians.

His friend, Hardings, also a pipe fitter at the same Continental Tire plant, was as round as Frazier was straight, and he traveled with a life-size cardboard cutout of the president. The two had been buddies for years. Both had been Democrats, Bill Clinton supporters, in fact, who had “walked away” to become fanatical Trumpians. This would be Frazier’s twelfth rally and Hardings’s second.

Further south in a suburb of Dallas, Texas, Dave Thompson briefly considered his choice of rides: the Chevrolet Suburban with the aluminum mag wheels and throaty growl or the classic 1983 Mercedes 240D? Both had a certain surprising flair for the fifty-eight-year-old deeply religious father of three. Lately, though, Thompson had been depressed. His ankle had swelled up for an unknown reason, and no matter how much he slept, he felt exhausted. He could barely muster enough energy to get through the day. But he’d been thinking a lot about God and about Donald Trump. End-times might be coming. There was some serious Satanic stuff going on in this country, and in his mind the president had been placed on this Earth to prepare the world for the next stage, which was going to be big. In the end he decided to fly to the rally in Minneapolis. Thompson was filled with new energy. Purpose. He felt like a man again, you might even say, and for as long as the wife approved, he resolved to hit up every rally he could while holding prayer groups at each one that might move the whole end-times process along.

Then there was Randall Thom. He was a native Minnesotan, a fifty-nine-year-old self-employed house painter and dog breeder, a former Marine, big boned and goateed, who walked with a rolling gait and traveled with a bottle of whiskey, a battery-operated bullhorn, several large flags, and banners exalting Donald Trump. He wore a T-shirt heavily decorated with the Stars and Stripes and the tag “#FRJ,” which stood for Front Row Joe. Thom was not just a Front Row Joe, though; he was the Front Row Joe. When newspaper reporters and TV folks referred to the “Front Row Joes,” they had in mind an ideal-looking Trump fanatic who traveled from rally to rally and was always the first in line and, once inside, crowded the rail right up by the president’s podium. This archetypal Trump fanatic was big and loud and he definitely had a goatee; he wasn’t very articulate and anything might set him off. While Snowden was in the front row at every rally—often along with Thompson and Frazier—they didn’t call themselves Front Row Joes. Snowden thought it was a bit too gauche. But Thom, he was that guy. The very one, and he wore it proudly. He would call everyone together for “the plan,” which usually involved trying to rally the rally goers with his bullhorn and not listening to the Secret Service or the police. Truth be told, many of his fellow superfans thought Thom was a boozing loudmouth. Though Thom said he was neck and neck with Snowden, claiming some fifty rallies to his credit, many doubted the number. It was Snowden who was the unofficial mayor of the line; everyone knew that and felt good about it.

This particular rally, Trump’s four hundredth since announcing his presidential campaign back on June 6, 2015, was scheduled for 7:00 P.M., Thursday, October 10, 2019, at Minneapolis’s Target Center. By 1:30 P.M. Wednesday (a bit late compared to many rallies), Snowden, Frazier, Thompson, Thom, and a flock of others were lined up and ready. As an urban arena in an often-frigid city, the Target Center was surrounded by parking garages connected by enclosed, elevated walkways, which meant that the front of the line was inside a carpeted skyway. When they found it, Snowden and the others were in for a surprise: none of them were first. Instead, ensconced in a padded, top-of-the-line camp chair, his shoes off and placed neatly under his chair, was a scraggly-haired young man in a blue-plaid shirt holding a bible of sorts (though far longer)—a collection of every tweet the president had ever made. Having recently survived cancer, Dan Nelson was seeing the world anew, which meant a fresh commitment to the actual Bible and to Donald Trump, who was remaking the world. This was Nelson’s third rally, and he had a thirty-six-hour jump on his nearest competitor, which was worth admiring since it spoke to his fantastic stamina and commitment—both valuable currencies in the arena.

As the afternoon wore on, fans trickled in, greeted each other with hugs and high fives, and claimed their grub stake with cheap, folding chairs, to be carried along as the line shifted and then abandoned when the rush for the door came. Rich Hardings’s life-size cardboard cutout of Trump went up. People really dug that, liked to have their picture taken with “him.” A Black man arrived in a red, white, and blue Stars and Stripes baseball shirt, and no one commented—African Americans were not just welcome at Trump rallies but encouraged. If you weren’t thinking too hard about it you might see the occasional Black face and think, huh, this is a surprisingly multiracial, heterogeneous crowd. This would be ridiculous, since even a huge Black turnout at a rally might be a hundred in a sea of twenty-two thousand.

Fifteen or twenty people and soon thirty, thirty-five, and, still so many hours before the event, something important happened: critical mass. Being there, you could feel it—a sudden sense of excitement. Of tension. Of momentum. A chain reaction, a growing throng, which is the greatest crowd multiplier of all—for the crowd, writes Elias Canetti, who fled Hitler in 1938 and won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1981, “always wants to grow; within the crowd there is equality; the crowd loves density. … The denser it is, the more people it attracts.” Who hasn’t seen a mob on the street and run toward it? The millions in Tahrir Square during the Arab Spring. Woodstock. Tiananmen Square before the tanks rolled in. The panhandling acrobats in Washington Square Park on a perfect spring day. A burning building. The crowd has immense power. It can pull down statues and can defeat armies and collapse governments. As it builds, the Trump rally crowd hints at something, suggests something: raw power. Power simmering. Power building. An urgency to be there now, before you missed it, before you could no longer get in and be a part of it.

There are an unlimited number of tickets to a Trump rally, no matter how many seats in the venue. The ticket, obtained online, is free, and no gatekeeper will ever ask for it. In an ideal world, from the organizer’s perspective, two hundred thousand tickets for a venue with twenty thousand seats would be claimed, and all those ticket holders would come to the arena hours or even days early. They would create a mob. A spectacle of hungry emotion cooking in the heat or freezing in the cold—suffering is the prelude to redemption—yearning, eager, anxious to get inside. The spectacle becomes its own high-octane fuel, its own catalyst. And anyone who opposes the man controlling the mob is opposing the mob’s power itself. It is unsettling and invigorating. It is a forewarning. “After all, great movements are popular movements, volcanic eruptions of human passions and emotional sentiments, stirred either by the cruel Goddess of Distress or by the firebrand of the word,” wrote Adolf Hitler in 1925.

2.

ARE YOU A GOOD PERSON?

My own journey to Minneapolis was circuitous. Over the past decade I had lived with former headhunters in a ten-thousand-square-mile roadless New Guinea swamp and spent weeks walking through the rain forest with the last nomadic hunter-gatherers in Borneo, eating squirrel, civet, bearcat, and song birds. I had traveled by bus across Afghanistan in the middle of a war. I had rattled from Bamako, Mali, to Dakar, Senegal, in a train so old and crowded that the best place to sit was with my feet hanging out the door. And once I’d traversed the Gobi Desert at the height of winter in a twenty-ton propane truck that had three flat tires and only two spares. Over some twenty years and eighty countries, I had poked into the deepest and most exotic crevices of everywhere much more than my own country. I had never reported a single American political story.

Which was startling, because I had been bottle-fed from birth on a heady milk of politics and journalism.

My father, Burton Hoffman with no middle name, came to Washington, D.C., in 1955 to work at Congressional Quarterly, then the preeminent publication covering the U.S. Congress. There he met my mother, a lovely WASP divorcée with an English degree and an entry-level editing job, and I was born five years later. My father soon moved up to the Washington Evening Star. At age three, I am told, I got lost in the White House during a holiday event for the press corps, and later that year I stood amidst the crowds lining Pennsylvania Avenue watching John F. Kennedy’s caisson pass by.

I don’t recall either of those events, but my first genuine political memory stands vivid. One summer’s day a pack of us kids were exploring on our own, and in the garage next door we discovered a dartboard stuck with steel-tipped darts and a six-foot-high, dry-mounted black-and-white poster of Barry Goldwater. What I remember most, the detail that makes this story stand out to me five decades later, is that we did not throw the darts at the dartboard and we did not throw them at the walls, or at each other, but at Goldwater himself. Not one of us was over eight years old that summer of ’65, but we all understood enough about American politics to know that Barry Goldwater stood for all the wrong things.

We moved soon after to a bigger house where the first thing my parents did was build bookshelves, lots of them, throughout the living and dining rooms. The Washington Evening Star and the Washington Post arrived daily and grew into vast piles. My father always said he read seven newspapers every day. Sometimes my sister and I got to go to the Star, where we marveled at the enormous room full of desks and typewriters and telephones and clattering UPI and AP wires; this was the beating heart of the world. We watched the presses roll (which they did every single day, itself a miracle), and we got our names in heavy typesetting lead from the kindly typesetters, and we nodded in admiration about the stories of reporters who’d started as jumpers and then become copy boys before finally getting beats of their own. That was the way it was done. Around the dinner table no one cared about athletes or movie stars.

We saw Ben Hecht’s The Front Page onstage and then the 1931 film. We carried with us the story of my mother’s tears when Adlai Stevenson lost to Dwight Eisenhower in 1956. In the summer of 1968 my father was sent to the Republican and Democratic National Conventions. He was gone for weeks, and we watched them, looking for him, on our 1963 Philco black-and-white television. They were presented to us as epic dramas, those conventions. The politicians, the newspapers and journalists covering them, were engaged in a holy calling; we were nourished from the beginning on the idea that politics and government and journalism were great. Noble. Not a swamp. Not fake, but the very opposite: the citadel of truth and honor where good people worked to make life better. If anyone were country-loving patriots it was journalists and liberal Democrats. “Look,” my father said. “Government exists to help those who cannot help themselves. Not for us. We’ll always be fine. You’re smart, you’ve grown up in a house full of ideas and reading, but not everyone has had that advantage. We don’t need laws that help us, but many other people do. So remember that.”

My parents weren’t privileged blue bloods but the children of working-class immigrants—the most American of mutts. My father’s parents, Abraham Hoffman and Adele Buxbaum, had fled the Pale as children, he from what is now Ukraine and she from Poland. They were Orthodox Jews who first ran a small grocery store in Brooklyn, New York, and then a bar in Newport, Rhode Island. My father’s declaration of atheism at seventeen (the same year he joined the army) was a break, to him, from an Old World ignorance and its cultural and religious chains. He was the first in his family to attend college (which he never finished), thanks to the G.I. Bill.

My mother was born in North Dakota, on a farm without running water. One year the snow was so deep they had to burn pieces of the barn to keep warm. Her mother, Esther, was one of nine children of Norwegian immigrants. In 1933, in the midst of the Depression and the Dust Bowl, a great-aunt married to a one-term congressman from Michigan got my grandfather a job in Washington, D.C., in the Department of Agriculture. My mother grew up in D.C. in a two-bedroom apartment, worked retail jobs from the age of fourteen, and graduated from the University of Maryland a lover of Collette and Carson McCullers.

They had both by some mysterious path found their way to books and ideas. Truth, in our house, was empirical. We proudly pursued logic, reason, critical thinking, a world not just without God, but also without Santa Claus, the Easter Bunny, or the Tooth Fairy.

“Be smart,” said my father.

“Think about it,” said my mother.

When my father caught me in a small lie he told me the story of the Boy Who Cried Wolf. I felt so guilty! Lies, it was clear, had consequences.

In 1972 my father quit his job as deputy managing editor of the Star and took the position of press secretary to Sargent Shriver, George McGovern’s running mate. On election night he grasped our hands and led us up onto the stage full of Shrivers and Kennedys and bright lights, and we stood in the center of the world as Shriver made his concession speech and a crook won reelection, soon to resign in disgrace.

In the midst of bussing and white flight, my sister and I attended District of Columbia public schools, where in senior high I was one of only five hundred or so whites in a system of eighteen thousand students. The principal was Black, the assistant principals were Black, most of my teachers were Black, the mayor was Black, as was most of the city council. There was nothing strange with that, for that was our city.

After a stint as the editor of the political magazine National Journal, my father left journalism and moved to the Hill as an aid to John Brademas, then the majority whip. Though he wasn’t a newspaperman any longer, my father installed a UPI and AP ticker in his office. He claimed to be unable to concentrate without the sound of the constant banging keys. Those, I think, were his favorite years. He loved working for Brademas and House Speaker Tip O’Neill, plotting and scheming, he used to say, alongside two very different men—one an intellectual, the other an old-line Boston Irish pol—who represented the best in liberal politics and democracy and saw government as a beautiful endeavor intent on lifting people to their very best.

One summer I worked in the U.S. House of Representatives folding room, an archaic place of giant mechanical machines that folded members’ newsletters. The next summer I did political organizing for the AFL-CIO. And the summer after that, between my junior and senior years of college, I worked on the reelection campaign of Maryland senator Paul Sarbanes. It was a heady time, in the midst of which I didn’t just represent Sarbanes at campaign events, but I fell in love.

In that moment I left politics behind. She was a reader and traveler who’d wandered through Mexico with a parrot and lived in Rome and her father was a writer. She said let’s travel, and we did. I’d never been out of the United States, but we finished college and lived in an Airstream trailer in the backyard of a group house for fifty bucks a month and painted houses for four months and saved enough to head to Europe, the Middle East, Asia.

I never looked back. I wrote about travel and technology and remote indigenous people, anything but politics, first for magazines and later in books. Then came the election of Donald Trump. For people like me, it was incomprehensible. The streets of Washington, D.C., on the day after the election were deserted, silent, as if the whole city was in mourning and couldn’t get out of bed.

My childhood had given me a clear foundation of values. Truth mattered. Science, reason, logic—the tenets of the enlightenment and liberalism were unassailable givens. Politics and government were a noble calling, as was journalism’s speaking truth to power. The exceptionalism of America, the quality that made it unlike anywhere else I’d traveled, was that anyone from anywhere could come here, like my own grandparents, and become American, be thought of and looked upon as an American by other Americans. That Emma Lazarus’s words on the Statue of Liberty articulated America’s greatest asset—an outward-looking, dynamic people who eschewed tribalism and thus became a true City on a Hill beckoning the huddled masses yearning to break free. This wasn’t merely snowflake-y compassion, but the very foundation of America’s cultural and economic dynamism, a continual influx of new Americans hungry for success and freedom, bringing new ideas and energies, novel talents to a continually growing nation. Even that most Republican of Republicans had said so at a time that now seemed long ago: “Anyone, from any corner of the world, can come to live in the United States and become an American,” said Ronald Reagan. “Here, is the one spot on earth where we have the brotherhood of man.” Trump’s signature campaign promise, the border wall, struck me as fundamentally un-American, the very antithesis of the limitless horizons of manifest destiny, of an idea—because that was what America had always been, first and foremost—about a nation that was different, that looked outward without fear and embraced change and the future.