Полная версия

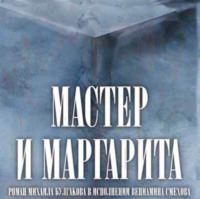

The Master and Margarita / Мастер и Маргарита. Книга для чтения на английском языке

A car had called for Zheldybin and, as a first priority, he had been taken, along with the investigators (this was around midnight) to the dead man’s apartment, where the sealing of his papers had been carried out, and only then had they all come to the morgue.

And now the men standing beside the remains of the deceased were conferring as to what would be better: to sew the severed head back onto the neck or to display the body in the Griboyedov hall with the dead man simply covered with a black cloth right up to the chin?

No, Mikhail Alexandrovich could not have telephoned anywhere, and Deniskin, Glukharev, Kvant and Beskudnikov were quite wrong to be shouting and indignant. At exactly midnight all twelve writers left the upper floor and went down to the restaurant. Here again they spoke ill of Mikhail Alexandrovich to themselves: all the tables on the veranda turned out, naturally, to be already occupied, and they had to stay and have dinner in those beautiful but stuffy halls.

And at exactly midnight in the first of those halls something crashed, rang out, rained down, began jumping. And straight away a thin male voice shouted out recklessly to the music: “Hallelujah!”[165] It was the renowned Griboyedov jazz band striking up. Faces covered in perspiration seemed to light up; the horses drawn on the ceiling appeared to come to life; there seemed to be added light in the lamps; and suddenly, as though they had broken loose, both halls began to dance, and after them the veranda began to dance as well.

Glukharev began to dance with the poetess Tamara Polumesyats, Kvant began to dance, Zhukopov the novelist began to dance with some film actress in a yellow dress. Dragoonsky and Cherdakchy were dancing, little Deniskin was dancing with the gigantic Navigator George, the beautiful architect Semyeikina-Gall was dancing in the tight grasp of a stranger in white canvas trousers. The regulars and invited guests were dancing, Muscovites and visitors, the writer Johann from Kronstadt, some Vitya Kuftik or other from Rostov, a director, apparently, with a purple rash completely covering his cheek, the most eminent representatives of the poetry subsection of MASSOLIT – that is, Pavianov, Bogokhulsky, Sladky, Shpichkin and Adelphina Buzdyak – were dancing, young men of unknown profession with crew cuts and padded shoulders were dancing, some very elderly man with a beard in which a little bit of spring onion had become lodged was dancing, and dancing with him was a sickly young girl, being eaten up by anaemia, in a crumpled little orange silk dress.

Bathed in sweat, waiters carried misted mugs of beer above their heads, shouting hoarsely and with hatred: “Sorry, Citizen!” Somewhere through a megaphone a voice commanded: “Karsky kebab, one! Venison, two! Imperial chitterlings!” The thin voice was no longer singing, but howling “Hallelujah!” The crashing of the golden cymbals in the jazz band at times drowned out the crashing of the crockery which the dishwashers slid down a sloping surface into the kitchen. In a word, hell.

And at midnight there was a vision in hell. Onto the veranda emerged a handsome black-eyed man in tails with a dagger of a beard who cast a regal gaze over his domains. It was said, it was said by mystics, that there was a time when the handsome man had not worn tails, but had been girdled with a broad leather belt, from which had protruded the butts of pistols, and his hair, black as a raven’s wing, had been tied with scarlet silk, and under his command a brig had sailed the Caribbean beneath a funereal black flag bearing a skull.

But no, no! The seductive mystics lie: there are no Caribbean Seas on earth, and desperate filibusters do not sail them, and a corvette does not give chase, and cannon smoke does not spread above the waves. There is nothing, and never was there anything either! There is, look, a sorry lime tree, there is a cast-iron railing and, beyond it, the boulevard… And the ice is melting in a bowl, and at the next table someone’s bloodshot, bull-like eyes can be seen, and it’s terrible, terrible. O gods, my gods, give me poison, poison!.

And suddenly at a table a word flew up: “Berlioz!” Suddenly the jazz band went to pieces and fell quiet, as though somebody had thumped it with their fist. “What, what, what, what?!” – “Berlioz!!!” And people started leaping up, started crying out.

Yes, a wave of grief surged up at the fearful news about Mikhail Alexandrovich. Someone was making a fuss, shouting that it was essential, at once, here and now, right on the spot, to compose some collective telegram and send it off immediately.

But what telegram, we’ll ask, and where to? And why should it be sent? Indeed, where to? And what good is any sort of telegram at all to the man whose flattened-out occiput[166] is now squeezed in the prosector’s rubber hands, whose neck is now being pricked by the curved needles of the professor? He’s dead, and no telegram is any good to him. It’s all over, we won’t burden the telegraph office any more.

Yes, he’s dead, dead. But us, we’re alive, you know![167]

Yes, a wave of grief surged up, but it held, held and started to abate, and someone had already returned to his table, and – at first stealthily, but then quite openly – had drunk some vodka and had taken a bite to eat. Indeed, chicken cutlets de volaille[168] weren’t to go to waste, were they? How can we help Mikhail Alexandrovich? By staying hungry? But us, you know, we’re alive!

Naturally, the piano was locked, the jazz band dispersed, a number of journalists left for their offices to write obituaries. It became known that Zheldybin had arrived from the morgue. He settled himself in the dead man’s office upstairs, and straight away the rumour spread that it would be him replacing Berlioz. Zheldybin summoned all twelve members of the board from the restaurant, and, at a meeting begun immediately in Berlioz’s office, they got down to a discussion of the pressing questions of the decoration of Griboyedov’s columned hall, of the transportation of the body to that hall from the morgue, of opening it to visitors, and of other things connected with the regrettable event.

But the restaurant began living its usual nocturnal life, and would have lived it until closing time – that is, until four o’clock in the morning – had there not occurred something really completely out of the ordinary that startled the restaurant’s guests much more than the news of Berlioz’s death.

The first to become agitated were the cab drivers in attendance at the gates of the Griboyedov House. One of them was heard to shout out, half-rising on his box:

“Cor! Just look at that!”

Following which, from out of the blue, a little light flared up by the cast-iron railings and began approaching the veranda. Those sitting at the tables began half-rising and peering, and saw that proceeding towards the restaurant together with the little light was a white apparition. When it got right up to the trellis, it was as if everyone became ossified at the tables, with pieces of sterlet on their forks and their eyes popping out. The doorman, who had at that moment come out through the doors of the restaurant’s cloakroom into the yard for a smoke, stamped out his cigarette and made to move towards the apparition with the obvious aim of barring its access to the restaurant, but for some reason failed to do so and stopped, smiling rather foolishly.

And the apparition, passing through an opening in the trellis, stepped unimpeded onto the veranda. At that point everyone saw it was no apparition at all, but Ivan Nikolayevich Bezdomny, the very well-known poet.

He was barefooted, in a ripped, off-white tolstovka, fastened onto the breast of which with a safety pin was a paper icon with a faded image of an unknown saint, and he was wearing striped white long johns. In his hand Ivan Nikolayevich was carrying a lighted wedding candle. Ivan Nikolayevich’s right cheek was covered in fresh scratches. It is difficult even to measure the depth of the silence that had come over the veranda. One of the waiters was seen to have beer flowing onto the floor from a mug that had tipped sideways.

The poet raised the candle above his head and said loudly:

“Hi, mates!” after which he glanced underneath the nearest table and exclaimed despondently: “No, he’s not here!”

Two voices were heard. A bass said pitilessly:

“A clear-cut case. Delirium tremens[169].”

And the second, female and frightened, uttered the words:

“How on earth did the police let him walk the streets looking like that?”

Ivan Nikolayevich heard this and responded:

“Twice they tried to detain me, in Skatertny and here on Bronnaya, but I hopped over a fence and, see, scratched my cheek!” At this point Ivan Nikolayevich raised the candle and exclaimed: “Brothers in literature!” (His hoarsened voice strengthened and became fervent.) “Listen to me, everyone! He has appeared! You must catch him straight away, or else he will bring about indescribable calamities!”

“What? What? What did he say? Who’s appeared?” came a rush of voices from all sides.

“A consultant!” replied Ivan. “And this consultant has just killed Misha Berlioz at Patriarch’s.”

Here the people from the hall indoors poured onto the veranda. The crowd moved closer around Ivan’s light.

“I’m sorry, I’m sorry, be more precise,” a quiet and polite voice was heard right by Ivan Nikolayevich’s ear. “Say what it is you mean, ‘killed’? Who killed him?”

“A foreign consultant, a professor and spy,” responded Ivan, looking round.

“And what is his name?” came the quiet question in his ear.

“That’s just it, the name!” cried Ivan in anguish. “If only I knew the name! I didn’t see the name on the visiting card properly… I can only remember the first letter, W, the name begins with a W! Whatever is that name beginning with a W?” Ivan asked of himself, clutching his forehead with his hand, and suddenly began muttering: “W, w, w. Wa… Wo. Washner? Wagner? Weiner? Wegner? Winter?” The hair on Ivan’s head started shifting with the effort.

“Wulf?” some woman shouted out compassionately.

Ivan got angry.

“Idiot!” he shouted, his eyes searching for the woman. “What’s Wulf got to do with it? Wulf’s not to blame for anything! Wo, what. No! I won’t remember like this! But I’ll tell you what, Citizens, ring the police straight away so they send out five motorcycles with machine guns to catch the Professor. And don’t forget to say there are two others with him: some lanky one in checks. a cracked pince-nez. and a fat black cat! And in the mean time I’ll search Griboyedov. I sense he’s here!”

Ivan lapsed into agitation, pushed those surrounding him away, began waving the candle about, spilling the wax over himself, and looking under the tables. At this point the words: “Get a doctor!” were heard, and somebody’s kindly, fleshy face, cleanshaven and well fed, wearing horn-rimmed spectacles, appeared before Ivan.

“Comrade Bezdomny,” this face began in a gala voice, “calm down! You’re upset by the death of our beloved Mikhail Alexandrovich… no, simply Misha Berlioz. We all understand it perfectly. You need a rest. Some comrades will see you to bed now, and you’ll doze off[170].”

“Do you understand,” Ivan interrupted, baring his teeth, “that the Professor must be caught? And you come pestering me with your stupid remarks! Cretin!”

“Comrade Bezdomny, pardon me,” the face replied, flushing, backing away, and already repenting getting mixed up in the matter[171].

“No, someone else, maybe, but you I won’t pardon,” said Ivan Nikolayevich with quiet hatred.

A spasm distorted his face; he quickly moved the candle from his right hand to his left, swung his arm out wide and struck the sympathetic face on the ear.

At this point it occurred to people to throw themselves upon Ivan – and they did. The candle went out, and a pair of spectacles, flying off a face, were instantly trampled upon[172]. Ivan emitted a terrifying war whoop – audible, to the excitement of all, even on the boulevard – and started to defend himself. The crockery falling from the tables began ringing, women began shouting.

While the waiters were tying the poet up with towels, a conversation was going on in the cloakroom between the commander of the brig and the doorman.

“Did you see he was in his underpants?” the pirate asked coldly.

“But after all, Archibald Archibaldovich,” replied the doorman in cowardly fashion, “how on earth can I not let them in if they’re members of MASSOLIT?”

“Did you see he was in his underpants?” repeated the pirate.

“For pity’s sake, Archibald Archibaldovich,” said the doorman, turning purple, “what ever can I do? I understand for myself there are ladies sitting on the veranda…”

“The ladies have nothing to do with it: it’s all one to the ladies,” replied the pirate, literally scorching the doorman with his eyes, “but it’s not all one to the police! A man in his underwear can proceed through the streets of Moscow only in one instance: if he’s going under police escort, and only to one place – the police station! And you, if you’re a doorman, ought to know that when you see such a man, you ought to begin whistling without a moment’s delay. Can you hear? Can you hear what’s happening on the veranda?”

At this point the doorman, beside himself, caught the sounds of some sort of rumbling, the crashing of crockery and women’s cries coming from the veranda.

“Well, and what am I to do with you for this?” the filibuster asked.

The skin on the doorman’s face assumed a typhoid hue, and his eyes were benumbed. He imagined that the black hair, now combed into a parting, had been covered in fiery silk. The dicky and tails[173] had disappeared, and, tucked into a belt, the handle of a pistol had appeared. The doorman pictured himself hanged from the foretop yardarm. With his own eyes he saw his own tongue poking out and his lifeless head fallen onto his shoulder, and he even heard the splashing of the waves over the ship’s side. The doorman’s knees sagged. But here the filibuster took pity on him and extinguished his sharp gaze.

“Watch out, Nikolai! This is the last time. We don’t need such doormen in the restaurant at any price. Go and get a job as a watchman in a church.” Having said this, the commander gave precise, clear, rapid commands: “Pantelei from the pantry. Policeman. Charge sheet. Vehicle. Psychiatric hospital.” And added: “Whistle!”

A quarter of an hour later an extremely astonished audience, not only in the restaurant, but on the boulevard itself as well, and in the windows of the houses looking out onto the garden of the restaurant, saw Pantelei, the doorman, a policeman, a waiter and the poet Ryukhin carrying out of Griboyedov’s gates a young man swaddled like a doll[174] who, in floods of tears, was spitting, attempting to hit specifically Ryukhin, and shouting for the entire boulevard to hear:

“Bastard!.. Bastard!”

The driver of a goods vehicle with an angry face was starting up his engine. Alongside, a cab driver was geeing up his horse, hitting it across the crupper with his lilac reins and shouting:

“Come and use the racehorse! I’ve taken people to the mental hospital before!”

All around the crowd was buzzing, discussing the unprecedented occurrence. In short, there was a vile, foul, seductive, swinish, scandalous scene, which ended only when the truck carried off from the gates of Griboyedov the unfortunate Ivan Nikolayevich, the policeman, Pantelei and Ryukhin.

6. Schizophrenia, Just as Had Been Said

When a man with a little pointed beard, robed in a white coat, came out into the waiting room of the renowned psychiatric clinic recently completed on a river bank outside Moscow, it was half-past one in the morning. Three hospital orderlies had their eyes glued to Ivan Nikolayevich, who was sitting on a couch. Here too was the extremely agitated poet Ryukhin. The towels with which Ivan Nikolayevich had been bound lay in a heap on the same couch. Ivan Nikolayevich’s hands and feet were free.

On seeing the man who had come in, Ryukhin paled, gave a cough and said timidly[175]:

“Hello, Doctor.”

The doctor bowed to Ryukhin, yet, while bowing, looked not at him, but at Ivan Nikolayevich. The latter sat completely motionless with an angry face, with knitted brows, and did not even stir at the entrance of the doctor.

“Here, Doctor,” began Ryukhin, for some reason in a mysterious whisper, glancing round fearfully at Ivan Nikolayevich, “is the well-known poet Ivan Bezdomny… and you see… we’re afraid it might be delirium tremens.”

“Has he been drinking heavily?” asked the doctor through his teeth.

“No, he used to have a drink, but not so much that.”

“Has he been trying to catch cockroaches, rats, little devils or scurrying dogs?”

“No,” replied Ryukhin with a start, “I saw him yesterday and this morning. He was perfectly well…”

“And why is he wearing long johns? Did you take him from his bed?”

“He came to the restaurant looking like that, Doctor…”

“Aha, aha,” said the doctor, highly satisfied, “and why the cuts? Has he been fighting with anyone?”

“He fell off a fence, and then in the restaurant he hit someone. and then someone else too.”

“Right, right, right,” said the doctor and, turning to Ivan, added: “Hello!”

“Hi there, wrecker!” replied Ivan, maliciously and loudly.

Ryukhin was so embarrassed that he did not dare raise his eyes to the polite doctor. But the latter was not in the least offended, and with his customary deft gesture he took off his spectacles; lifting the tail of his coat, he put them away in the back pocket of his trousers, and then he asked Ivan:

“How old are you?”

“Honestly, you can all leave me alone and go to the devil!” Ivan cried rudely, and turned away.

“Why ever are you getting angry? Have I said anything unpleasant to you?”

“I’m twenty-three,” Ivan began excitedly, “and I shall be putting in a complaint about you all. And about you especially, you worm!” he addressed himself to Ryukhin individually.

“And what is it you want to complain about[176]?”

“The fact that I, a healthy man, was seized and dragged here to the madhouse by force!” replied Ivan in fury.

Here Ryukhin peered closely at Ivan and turned cold: there was definitely no madness in his eyes. From being lacklustre, as they had been at Griboyedov, they had turned into the former clear ones.

“Good gracious!” thought Ryukhin in fright. “Is he actually sane? What nonsense this is! Why ever, indeed, did we drag him here? He’s sane, sane, only his face is all scratched…”

“You are not,” began the doctor calmly, sitting down on a white stool with a shiny leg, “in the madhouse, but in a clinic, where nobody will think of detaining you if there is no need for it.”

Ivan Nikolayevich gave him a mistrustful sidelong look, but muttered nevertheless:

“The Lord be praised! One sane man has at last come to light among the idiots, the foremost of whom is that talentless dunderhead Sashka!”

“Who’s this talentless Sashka?” enquired the doctor.

“There he is, Ryukhin!” Ivan replied, and jabbed a dirty finger in Ryukhin’s direction.

The latter flared up[177] in indignation.

“That’s what he gives me instead of a thank you!” he thought bitterly. “For my having shown some concern for him! He really is a scumbag!”

“A typical petty kulak in his psychology,” began Ivan Nikolayevich, who was evidently impatient to denounce Ryukhin, “and a petty kulak, what’s more, carefully disguising himself as a proletarian. Look at his dreary physiognomy and compare it with that sonorous verse he composed for the first of the month! Hee-hee-hee… ‘Soar up!’ and ‘Soar forth!’… but you take a look inside him – what’s he thinking there. it’ll make you gasp!” And Ivan Nikolayevich broke into sinister laughter.

Ryukhin was breathing heavily, was red, and was thinking of only one thing – that he had warmed a snake at his breast, that he had shown concern for someone who had turned out to be, when tested, a spiteful enemy. And the main thing was, nothing could be done about it either: you couldn’t trade insults with a madman, could you?!

“And why precisely have you been delivered to us?” asked the doctor, after attentively hearing out Bezdomny’s denunciations.

“The devil take them, the stupid oafs! Seized me, tied me up with rags of some sort and dragged me out here in a truck!”

“Permit me to ask you why you arrived at the restaurant in just your underwear?”

“There’s nothing surprising in that,” replied Ivan. “I went to the Moscow River to bathe, and well, I had my clobber nicked, and this trash was left! I couldn’t go around Moscow naked, could I? I put on what there was, because I was hurrying to Griboyedov’s restaurant.”

The doctor looked enquiringly at Ryukhin, and the latter mumbled sullenly:

“That’s what the restaurant’s called.”

“Aha,” said the doctor, “and why were you hurrying so? Some business meeting or other?”

“I’m trying to catch a consultant,” Ivan Nikolayevich replied, and looked around anxiously.

“What consultant?”

“Do you know Berlioz?” asked Ivan meaningfully.

“That’s… the composer?”[178]

Ivan became upset.

“What composer? Ah yes. Of course not! The composer just shares Misha Berlioz’s name.”

Ryukhin did not want to say anything, but he had to explain:

“Berlioz, the secretary of MASSOLIT, was run over by a tram this evening at Patriarch’s.”

“Don’t make things up[179] – you don’t know anything!” Ivan grew angry with Ryukhin. “It was me, not you, that was there when it happened! He deliberately set him up to go under the tram!”

“Pushed him?”

“What’s ‘pushed’ got to do with it?” exclaimed Ivan, getting angry at the general slow-wittedness. “Someone like that doesn’t even need to push! He can get up to such tricks, just you watch out! He knew in advance that Berlioz was going to go under the tram!”

“And did anyone other than you see this consultant?” “That’s precisely the trouble: it was only Berlioz and me.” “Right. And what measures did you take to catch this murderer?” Here the doctor turned and threw a glance at a woman in a white coat sitting to one side at a desk. She pulled out a sheet of paper and began filling in the empty spaces in its columns.

“Here’s what measures. I picked up a candle in the kitchen…”

“This one here?” asked the doctor, indicating the broken candle lying beside an icon on the desk in front of the woman.

“That very one, and.”

“And why the icon?”

“Well, yes, the icon.” Ivan blushed, “it was the icon that frightened them more than anything” – and he again jabbed his finger in Ryukhin’s direction – “but the thing is that he, the consultant, he. let’s talk plainly. he’s in cahoots with[180] unclean spirits. and it won’t be so simple to catch him.”

The orderlies stood to attention for some reason and did not take their eyes off Ivan.

“Yes,” continued Ivan, “he’s in cahoots! That’s an incontrovertible fact[181]. He’s spoken personally with Pontius Pilate. And there’s no reason to look at me like that! I’m telling the truth! He saw everything – the balcony, the palms. In short, he was with Pontius Pilate, I can vouch for it[182].”

“Well then, well then.”

“Well, and so I pinned the icon on my chest and ran off…”

Suddenly at this point a clock struck twice.

“Oho-ho!” exclaimed Ivan, and rose from the couch. “Two o’clock, and I’m wasting time with you! I’m sorry, where’s the telephone?”

“Let him get to the telephone,” the doctor commanded the orderlies.

Ivan grasped the receiver, and at the same time the woman quietly asked Ryukhin:

“Is he married?”

“Single,” replied Ryukhin fearfully.

“A union member?”

“Yes.”

“Is that the police?” Ivan shouted into the receiver. “Is that the police? Comrade duty officer, make arrangements immediately for five motorcycles with machine guns to be sent out to capture a foreign consultant. What? Come and pick me up, I’ll go with you myself… It’s the poet Bezdomny speaking from the madhouse… What’s your address?” Bezdomny asked the doctor in a whisper, covering the receiver with his palm, and then he again shouted into the receiver: “Are you listening? Hello!. Disgraceful!” Ivan suddenly wailed, and he flung the receiver against the wall. Then he turned to the doctor, reached out his hand to him, said drily “Goodbye” and prepared to leave.