Полная версия

Love In, Love Out

2

What is Anxiety?

In this age of ever-growing anxiety, it’s becoming increasingly difficult for the average parent to know what is a healthy level of anxiety in their children, and what is something to be more concerned about. Our kids face a multitude of challenges at all stages of their development: from toddlers with nightmares, to primary school children with separation anxiety and tummy pains, to self-conscious adolescents who find social situations terrifying.

Anxieties are common in childhood, and are often part and parcel of growing up. Everyone experiences anxiety, which is a product of our ‘tricky’ survival brains29 trying to cope with life’s constantly changing demands. A useful way of looking at anxiety is as a simple formula: add up all the things that cause our children stress, and then subtract their beliefs about their ability to cope. The net result is their anxiety level.30 So it’s how a child copes with their anxiety that marks the difference between them thriving in their daily lives or having real difficulty meeting new experiences with open arms.

Your response to your child’s anxiety is a crucial factor in how your child will cope. With their supportive guidance, parents like you hold the key to anchoring their children with safety and connection. From this strong foundation, you and your child can work on problem-solving strategies together to help alleviate their anxiety.

That is why it’s so important for you to be able to recognise when anxiety is beginning to affect your child’s daily life and their ability to function.

Anxiety made simple

Question: What is anxiety, and is it normal?

Answer: Everyone feels anxious sometimes. It’s normal to feel a bit anxious when you’re meeting someone new, when you’ve just got on a rollercoaster, when you’ve been asked to speak in class or are waiting just before a test. Just like adults, some kids feel it only a bit, while others feel it a lot more.

When anxiety comes, you’ll know that something doesn’t feel quite right, but you may not have the words to explain what’s happening to you. This is particularly true for children and teenagers. You may feel like something bad might happen to you or to someone you care about. You might also be angry or sad and want to avoid doing things, or simply wish to stay at home.

Anxiety is the body’s alarm system that has always helped human beings to survive. It works so well that it kicks in even when it’s not needed, like when we believe there is danger when there is none, or when we start to ask ourselves ‘What if’ something terrible happens.

People who are feeling anxious are scanning for danger, and are mega alert to the body’s alarm signals. That’s why anxiety can feel so exhausting!

Anxiety is not a sign of anything being wrong or of being weak. It’s a sign that your strong, healthy brain is doing exactly what it’s meant to do to protect you from danger. Anxiety doesn’t care if the threat is real or imagined, because our brain would rather keep us safe than be sorry.

Sometimes our brain goes overboard in trying to protect us. When this happens, it sets off a chain reaction of nasty feelings in our bodies. Feeling bad makes us think anxious thoughts, which makes us even more anxious, like a vicious circle. It’s as if we’re ready for action, but there’s no enemy, so tension builds up in our bodies without having a chance to be let out!

Anxiety as a problem

Anxiety becomes a problem when it affects a child’s sense of who they are, their relationships and their engagement with school and other activities. Anxiety becomes a problem when a child’s worries – whether their thoughts, feelings or physical sensations – are making them avoid situations, which in turn restricts their learning and enjoyment of life.

Distinguishing anxiety from normal fears is important. Throughout childhood, we all naturally experience transient fears that arise in line with our ability to recognise and understand potential dangers in our environment.

When a child is young, fears seem to be immediate and tangible, like separation from a loved one or a fear of strangers. As the child gets older, fears seem to become more abstract, centring on thoughts that anticipate problems (‘what if?’) and focusing on the less tangible (bad dreams, someone getting hurt, or struggling at school).31 Children are expected to ‘grow out of’ many of these fears as they develop.

Sadly, this is more difficult for some children than for others, which is why it’s important to focus on what is happening in your child’s world. If you feel that anxiety is having a significant impact on your child’s daily life and ability to function, then it may be time to seek some professional support in guiding you and your child forward.

Basic symptoms of anxiety

Many children have the problems listed below at some point, but if your child has been struggling with one or more of these symptoms more days than not for the past six months, it may be time to talk to your GP.

Your GP can advise you about reputable local support services. These might include a psychologist, psychotherapist, play therapist or counsellor.

Excessive anxiety and worry about a number of events or activities

Worry that is hard to control

Restlessness or feeling keyed up or on edge

Becoming easily fatigued

Difficulty concentrating or mind going blank

Irritability

Muscle tension

Sleep problems: difficulty falling or staying asleep, restlessness, or unsatisfying sleep

Difficulties in school, in social settings, dealing with others32

Your doctor will also want to rule out other potential causes of anxiety, including medical conditions, the side-effects of medication, drug or alcohol use, and any other mental health concerns.

Adrenaline and our bodies33

There are very real reasons why your body feels the way it does when you’re anxious. When there’s nothing to fight or run away from, there’s nothing to burn up the fight-flight-freeze fuel – adrenaline – that’s rushing through your body.

Adrenaline is a stress hormone whose job it is to get you up and moving, often for positive reasons, like excitement, meeting a deadline or running a race. This big boost of energy helps us to do our best. But adrenaline also rushes into our bodies when we’re feeling anxious, worried or threatened, when there’s no deadline to meet or race to run, so there’s nowhere for it to go.

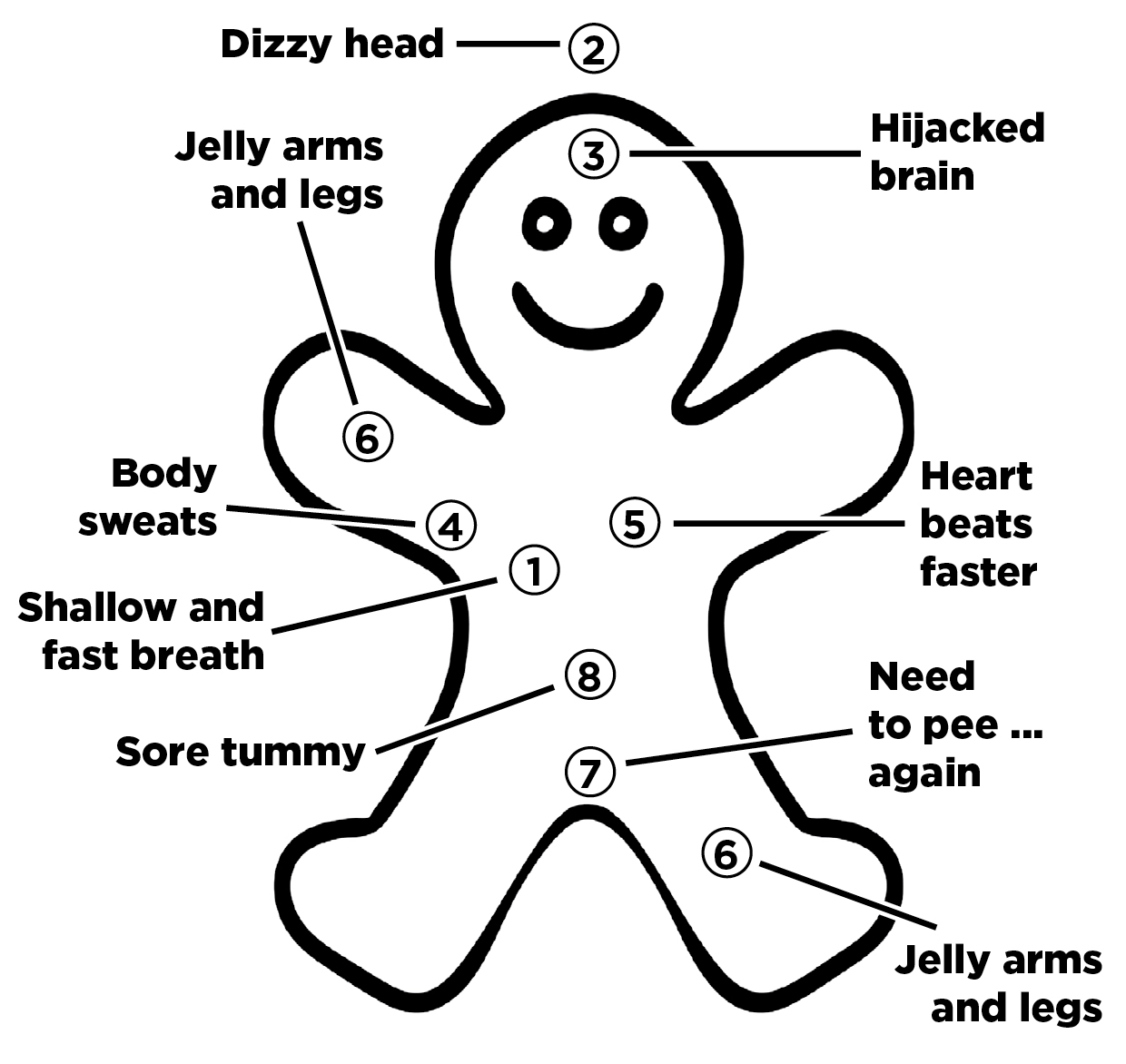

Here are some of the things you might feel when adrenaline builds up and why you might feel them when you’re anxious:

1. Shallow and fast breath

What’s happening? Your brain tells your body to stop wasting oxygen – instead of using it on strong, deep breaths, your body is told to send it to the muscles so they can fight or run away.

How you might feel. Your breathing changes from strong, slow, deep breaths to fast, little breaths. You might feel puffed or a bit breathless. Your cheeks might blush red and your face might feel warm.

2. Dizzy head

What’s happening? If you don’t fight or run away, levels of oxygen build up in your body and carbon dioxide levels drop from all that fast breathing.

How you might feel. Dizzy, confused or sick.

3. Hijacked brain

What’s happening? When you have an anxious adrenaline rush, other feelings such as anger or sadness might turn up to high volume as well. When your thoughts are racing, it’s hard to think clearly with the logical, calming part of your brain, the prefrontal cortex.

How you might feel. Angry or sad, as though you want to burst into tears, sometimes for no reason at all. Your ‘wise leader’ – the prefrontal cortex – shuts down.

4. Body sweats

What’s happening? Your body cools itself down by sweating so it doesn’t overheat if you have to fight or run away.

How you might feel. Clammy or sweaty, even if it’s cold out.

5. Heart beats faster

What’s happening? Your heart beats faster and your pulse rises to get the oxygen around your body, especially to the arms and legs, allowing you to run away or attack.

How you might feel. Your heart can feel like it’s racing and you might also feel sick. This can feel scary, like a heart attack. It’s OK, though – you’re perfectly safe.

6. Jelly arms and legs

What’s happening? Fuel gets sent to your bigger muscles in the arms (in case you need to fight) and the legs (in case you need to run away).

How you might feel. Your arms and legs might feel tight or wobbly.

7. Need to pee … again

What’s happening? Adrenaline can make you want to pee. We know it happens, but we don’t really know why.

How you might feel. As if your bladder’s full and you want to empty it.

8. Sore tummy

What’s happening? The digestive system shuts down so the fuel it was using to digest food can be used by your arms and legs in case you have to fight or run away.

How you might feel. As if there are butterflies in your tummy. You might also feel sick, as if you’re going to vomit – and your mouth might feel a bit dry.

With all these things happening in your body, no wonder you might feel exhausted, shaky and weak after the adrenaline has died down!

The causes of anxiety

Finding the causes of a child’s problematic anxiety can be complicated. They can often assume the form of an interweaving web that might take quite some time to untangle. Sometimes the root causes of anxiety aren’t as clear as we’d like them to be, but that doesn’t mean that an anxious child won’t benefit hugely from our compassion, anchoring support and the approaches outlined in this book.

Common reasons for difficulty coping with anxiety range from a child’s unique temperament or personality, to what a child has gleaned from observing their parents and key adults, the presence of any traumatic events or ‘anxiety triggers’ in their lives, all the way to being vulnerable to the impact of the wider society in which they live.

All these interacting factors at play can make it extremely difficult for children to share their anxious feelings, for parents to navigate the best way forward, for teachers to respond appropriately, and for doctors, therapists and others to support children and their families.

Many of the parents I meet are hugely eager to find a reason for their child’s anxiety so that they can begin to make helpful changes to their environment and identify the most appropriate ways to support them.

Of course it can certainly help to know what triggers your child’s anxiety and what eases it, so you can better equip them with the tools to identify and manage it. But a vital precursor to introducing these problem-solving tools into your child’s life is the role you as a parent play in anchoring them back to safety during their wobbly moments, which crucially involves you feeling calm and nurtured in the first instance.

However, I would urge you not to fixate on trying to find a reason for your child’s anxiety, as it may not always be clear. What’s more important is to take each day as it comes, and to respond calmly to your child’s emotions with empathy and compassion in the moment.

Regardless of the specific reason or reasons for your child’s anxiety, the experience of anxiety itself is quite similar in everyone. This is simply because as human beings we all share the same survival response to threatening situations, which negatively impacts our thoughts, feelings, body sensations and behaviour. Whilst the intensity of this response can vary between humans, the feeling of anxiety is universal.

For that reason the techniques I introduce in this book apply to any child of any age, irrespective of the reasons why they may be anxious.

Although the experience of anxiety is much the same for everyone, we’re now experiencing unprecedented levels of anxiety throughout our lives. Why is that, and how can we reduce the impact of negative social factors on children’s well-being?

The Age of Anxiety

We had the Stone Age, the Iron Age, the Bronze Age, the Industrial Age and the Technological Age. Now we have the Age of Anxiety. Why do I say that? We are bombarded with messages from the world about all the things that are dangerous, could be dangerous or will be dangerous.34

Anxiety is rife among children today, and I’ve seen a massive increase in the number of children being referred to me with this condition in recent years. Even though anxiety is the most common mental health issue facing children in the Western world today35 and the most prevalent psychological disorder in schoolchildren, it has been described as a ‘silent epidemic’ as it can often go undetected and untreated.

Because children who suffer from anxiety don’t necessarily draw attention to themselves and often present as well behaved, they can frequently be left to suffer in silence as they’re overlooked or mistaken for being shy. Some children might act out angrily in an effort to cope with their hidden anxious feelings, which may also lead to misunderstanding, while others hide their anxiety behind a veil of perfectionism, petrified of doing anything wrong or of making the tiniest mistake.

Anxiety hides behind many masks, which cover up a multitude of scary thoughts. A child hiding their anxiety can be really lonely, as they continue to suffer while concealing their real self from the world. A child’s real self can be itching to get out – if only they knew how or had the courage to let it happen. Being isolated like this also means that the child is alone with their own thoughts, usually preoccupied with something that happened in the past or that might happen in the future, which makes it hard for them to live in the moment.

Although we have a better standard of living than previous generations, and have come on leaps and bounds in terms of our health care, we still have a very long way to go. The irony is that the world we now live in is actually contributing to anxiety for both parents and children. The demands of the world are increasing, which makes us feel threatened and shakes our faith in our ability to cope.

Deciding what’s important: different kinds of goals

One of the ways in which the world we live in makes us anxious can be related to the kinds of goals we choose to pursue. Some goals are bigger-picture; others are very specific.

An intrinsic goal is one very much related to the activity that achieves it, where the enjoyment comes from the journey as opposed to the end result. Intrinsic goals include spending quality time with loved ones, living life according to one’s values, pursuing a dream, or anything that gives life meaning.

On the other hand, an extrinsic goal is distantly related to the activities that achieve them which are often seen as imposed by the outside world. Examples include achieving high marks in school, winning sports games, achieving high status and looking a certain way.

There has been a continual shift away from intrinsic goals in our pressurised modern world in favour of extrinsic goals. This is to our detriment, as the pursuit of extrinsic at the expense of intrinsic goals has been linked to increased rates of anxiety and depression. This makes sense, as what we do to pursue extrinsic goals is often less satisfying than when we follow our intrinsic goals. What’s more, we often have less control over how successfully we meet our extrinsic goals for the simple reason that they rely on external forces. An over-emphasis on extrinsic goals is linked to an overactive Threat system feeding our Drive system; on the other hand, enjoying the process of meeting our intrinsic goals nurtures our Soothing system, leading to more positive Drive in our lives.

Our Drive system is frequently over-stimulated because we live in a society that encourages us to want more, to have more and to be more.36 This ‘scarcity culture’ occurs when everyone is hyper-aware of what they lack:

Everything from safety and love to money and resources feels restricted or lacking. We spend inordinate amounts of time calculating how much we have, want and don’t have and how much everyone else has, needs and wants.37

Our caveman brains and the negativity bias

Our Age of Anxiety is, in great part, the result of trying to do today’s jobs with yesterday’s tools!38

Our brains haven’t changed much if at all since the human race began, but the kinds of threats we face have. Back in the days of the caveman, when human beings were presented with many more physical dangers, it was our brains that helped us to survive basic and very tangible threats, such as predators.

Our brains have always tricked us by overestimating threats and comparing us unfavourably to others – they do this to keep us safe. If we think things are worse than they are – and that we’re at greater risk than we are – we’ll be more careful and have a better chance of survival.

Part of the reason that we’re still afraid of what might happen to us, and hyper-aware of what we lack, is because of this age-old trick that our brains play on us in order to protect us. This also includes our inner critical voice, ever present to give its opinion at the drop of a hat.

Incredibly, for every negative thing that happens, we need five positives to balance it out! This is where making a conscious effort to be kind to ourselves and others comes into play.

But why does this kind of negative focus have so much staying power? The negativity bias – our natural tendency to attend to and respond more readily to negative information – is a very real force determining how we behave, and has been found in babies as young as three months old. Our collective negativity bias arises from both innate predispositions and our learned experience: nature and nurture combined.

Our negativity bias plays a significant role in our views about ourselves, our emotions, our ability to take in information and our decision-making. Left unchecked, it can become a serious impediment to good mental health, as it has been found to be synonymous with anxiety and depression.39

Modern technology meets tricky brain

Our contemporary epidemic of anxiety arises from trying to cope with today’s challenges (including a huge increase in the availability and power of technology) with yesterday’s tools (our caveman brain). When the pressures of modern life meet the ancient circuitry of our brains, anxiety happens. I call this ‘the perfect storm’, except there’s nothing perfect about it.

In our caveman days, our brains convinced us that we were weaker and slower than our predators in an effort to protect us; today, our brains still gauge our social and personal worth based on how we feel we stack up against others. As a result, we constantly make comparisons between ourselves and those around us across a variety of domains, like attractiveness, wealth, intelligence and success. This is ‘Social Comparison Theory.’40

With the advent and almost universal use of social media, people have even more ways to compare themselves to others, 24 hours a day. All of this makes for an awful lot of pressure on a daily basis. Constant exposure to what everyone else is doing can make us hyper-aware of what we’re not doing, which in turn can lead to FOMO (fear of missing out), particularly for younger people. Add to that the constant stream of everyone else’s ‘highlight reels’ (i.e. the best bits of their lives that people choose to portray on social media), and it’s easy to feel like you don’t quite measure up. If that’s so often true for us adults, imagine how your developing and impressionable child might feel!

Once children reach middle childhood they develop an increased awareness of the world beyond their family and close friends. This is when the pressures of comparing themselves to others and conforming to peers becomes apparent. In addition, children now realise that their performance in school must really matter, and that’s why the grown-ups keep harping on about it …

It’s also around this stage in a child’s development that bullying can become an inescapable problem, which relates to how children judge themselves against others. Bullying has been around forever, but it’s now relentless because of social media. Where once a bullied child got to recover in the evening at home with their family, now the bullying follows them online after school; they can carry it around in their pocket and check in at any time. Whilst there are many advantages to the advent of the smartphone and social media, for children, especially those prone to anxiety, being ‘on’ all the time keeps their Threat system on high alert, which takes away from their precious downtime.

The burden of great expectations

Dr Colman Noctor, a child and adolescent psychotherapist, puts it this way41:

Happiness = Expectations – Reality42

With a constant stream of the ‘best bits’ of everyone else’s lives in our pockets – best hair days, school reports, amazing holidays, you name it – we now live in a world that drives our expectations up, up, up. As a result, we’ve ended up with a situation in which our expectations often far exceed our capacity to meet them.

Children often have high expectations for themselves based on both internal and external pressures – expectations that don’t look all that unlike our own: ‘If I win, then I’ll be happy’; ‘If I can look this way, then I’ll be happy.’

If children were rewarded more for showing kindness to themselves and others, they’d be much happier and less anxious. They wouldn’t care as much about getting medals or the newest haircut. They wouldn’t be struggling for the impossible. Instead they’d be encouraged to look inside and find something with much greater meaning.

It’s up to us, step by step and little by little, to go back to the basics of the more important things in life if we feel that external pressures are significantly impacting on our kids. Naturally, we live in the society that we live in, and our power to change it is limited. But the culture that we create within our homes and within our schools is one that we can have a real influence over.

Managing our own expectations of our children is an important part of helping them to manage their expectations, as is trying not to live our lives through them – although this is easier said than done. Children have a right to make their own mistakes and to follow their own paths. Remember that supporting them unconditionally through the jungle of life is something they won’t get from anyone else. You are their everything in this regard, even though that may be hard to believe sometimes, especially if you’re the parent of a teenager!

Doing it for the kids: checking our motivations as parents

Your role as your child’s support system is absolutely crucial. When pressure is coming from everywhere else, you’re their stable base; you can remind them who they really are, and what really matters.

Having gone through the ups and downs of life yourself, you also have gained perspective, but you must exercise it with caution. Helping your child to realise that their feelings and thoughts are transient, and that there is light at the end of the dark tunnel is one good use of this skill. Nagging children excessively about studying or talking them into doing an activity everyone else is doing is not as good, because it’s not necessarily in their best interest.

It’s good to encourage children and show them how much you believe in them and in their ability to follow their own star.

But first, remember to ask yourself: ‘Am I doing this for me, for someone else or for them?’ If it’s mostly for them, then you’re onto a winner.