Полная версия

Love In, Love Out

We need to treat ourselves with kindness as we would a good friend in the same situation – with gentleness, warmth, patience and encouragement: ‘May I be kind to myself in this moment.’

With this kindness, we can take action, because compassion is best understood as something that we do in response to a difficult situation: ‘Love in for myself; love out towards my child, and bringing calm and connection to this difficult moment.’4,5

Taking a minute to reset

An alternative meaning to Love in, love out came from one of my writing mentors. He interpreted it as a mantra involving the power of the breath to calm us down by switching our brain’s fight-flight-freeze mode to a gentler, more rational mode. He liked that peaceful, rhythmic quality about it: Love in, love out. Love in, love out. It’s a soothing message of compassion for you – and your child.

Originally derived from Hinduism and Buddhism, a mantra is a word, phrase or sound believed to have a special spiritual power, which is repeated to aid concentration in meditation or prayer and expresses a strong belief. A mantra is a great tool for both parents and children to encourage us to press pause on a difficult situation or to spur us on when we need a good boost.

Because our inner voice has huge power over how we feel about ourselves and how we make sense of and respond to our experiences, compassionate mantras like Love in, love out balance the negative inner voice we often tune into during our hardest moments.

Many of us – and especially parents – are grandmasters at beating ourselves up at every opportunity we get. Being nice to ourselves may feel really alien to some of us. It’s as if we think that being hard on ourselves will keep us ‘in line’ and make us better parents. On the contrary; being self-critical doesn’t prevent bad things from happening, and it can actually make things worse for both us and our kids.

Being self-critical can be really harmful to both our emotional and physical health and is linked to everything from depression to anxiety to high blood pressure to a general sense of dissatisfaction with life. Just like a physical attack sends our brain’s fight-flight-freeze response into overdrive, so does an emotional attack, even if we’re directing it at ourselves.6 At times, modern-day man’s worst predator can be himself.

To add insult to injury, when we engage in self-criticism, not only are we the ‘attacked’ but we’re also the ‘attacker’ – making the process doubly exhausting. With all this going on in our brains, no wonder self-criticism can lead to anxiety. To make matters worse, self-criticism can also arise from anxiety. This is because people with anxiety can feel alone in their pain and powerless to do anything about it, and they criticise themselves for it.

Mantras are in essence the antidote to our brain’s age-old tendency towards negativity and they ensure that self-kindness trumps self-blame. I’m down with that. It’s about being mindful of how you talk to – and about – yourself, because your words are powerful.7 Examples include: ‘Breathe’; ‘It’s OK’; ‘This shall pass’; ‘It is what it is’; ‘Try a hug’; ‘Namaste’; or whichever other positive words float your boat!

Practising being positive about ourselves, to ourselves, is a hell of a lot easier when all is rosy in the family garden, when your kids are getting along and are in a good emotional place. But it’s actually during the most challenging moments, when our kids are highly emotional and are testing our patience, that taking a mindful pause is one of the best tools you can hone. We may not be able to control their out-of-control behaviour, but we can try our best to respond to them in a calmer way.

Compassion ‘in’ and ‘out’ trays

Love in, love out can also be seen as a poignant offering from parents to their children.8

Think of the ‘in’ and ‘out’ trays you’d find in an office. If a parent focuses on putting love in to their child, the child is then enabled to give love out to themselves, their parents, families, friends, teachers and communities. That’s a lot of ‘outs’ for one ‘in’, isn’t it?

This is why the child–parent relationship is so important in making a child feel safe, comfortable in their own skin, able to manage big feelings and show compassion towards others. When we put love in to a child it builds a strong foundation for the child to develop compassion for themselves, to nurture important social and emotional connections, and to grow lifelong resilience.

With all these meanings attached to it, Love in, love out grew into something pretty special for me. That is what I intend to offer you in this book. If I can pour my heart into you and your parenting through sharing my vulnerabilities and the wisdom my clients have gifted me with, then Love in, love out may hopefully become something special for you too.

If you’d like to try a Love in, love out meditation, flip ahead to here.

Why a compassionate approach?

I was a little stressed myself while I was preparing to contribute to a TV documentary exploring our modern-day experience of stress9 – the irony! I was trying to decide which therapeutic approach would be most helpful for father-of-one Jonathan, and was more than a little nervous about my skills in psychology being exposed on camera in front of the whole nation.

I wanted to choose the best approach to help Jonathan to feel less stressed and overwhelmed in his daily life. The goal was for him to focus on what mattered most to him, such as his connection with his family and living more in the moment.

But I needn’t have worried about my performance. Compassion did its thing, and I felt like the privileged messenger.

It being television, the production team would have preferred me to come up with a therapeutic process that was more visual: daring him to jump off a diving board, for instance, or taking a relaxing walk through a beautiful meadow. Instead, Jonathan’s journey of self-discovery took its natural course when we began to focus on compassion.

The healing properties of compassion have been celebrated for centuries. Compassion has always been considered a vital quality by both Western and Eastern philosophies and religions, and now even has its own therapy called ‘compassion-focused therapy’, which is gaining a following among psychologists, psychiatrists and other medical professionals.

To find out more about compassionate parenting in action, flip ahead to here.

The origin of the word ‘compassion’ reveals its powerful meaning and significance. Compati in Latin is ‘suffer with’, so ‘compassion’ is, by definition, relational; that is, it requires a relationship with the people around us. Compassion requires sharing in the experience of suffering – and if we accept that there is suffering to be had, we’re recognising that the human experience – life – is imperfect.

Compassion is the realisation that all human beings make mistakes, have regrets, and struggle with feelings of inadequacy and disappointment – and that we’re all in the same boat together. Knowing this somehow brings comfort:

The pain I feel in difficult times is the same pain you feel in difficult times. The triggers are different, the circumstances are different, the degree of pain is different, but the process is the same. You can’t always get what you want. This is true for everyone, even the Rolling Stones.10

To have compassion for others, you must first notice that they’re suffering, then be moved by their suffering, and feel warmth and caring and a desire to help them. When they make mistakes, you offer understanding and kindness, rather than judgement.

Compassion not only involves a sensitivity to our own and other people’s distress, but a motivation to prevent or alleviate it.11 Being compassionate means that someone else’s pain becomes your pain, and that crucially, you take steps to do something about it.

Having compassion for yourself during hard moments – like when you’re raising your children – means watching out for how you’re feeling, and treating yourself with the same kindness and understanding you’d give others. It also means seeing failures as part of the human condition, and having a balanced awareness of painful thoughts and emotions.

Self-compassion is just as important in improving our overall health as having compassion for others, with multiple studies showing that greater self-compassion is linked to less anxiety and depression.12 One of the reasons for this is that self-compassionate people are more likely to accept their emotions without judgement and are less likely to worry than those who lack self-compassion.13

Accepting our imperfections with kindness appears to break the cycle of negativity and deactivates the body’s fight-flight-freeze response.

Compassion is a foundation for sharing our aliveness and building a more humane world.14

Like the ripple created by throwing a pebble in a pond, one act of compassion can have an effect that may reach around the world.15 If one single act of compassion can have such an impact, imagine the potential impact of parents being compassionate towards themselves on a regular basis. As they witness their parents emerging calmer and more confident, the ripple will affect these children’s own relationships with themselves and others.

Many parents I meet are stuck in patterns of self-blame and feel powerless to help their children who are struggling with their big feelings, be they anxiety, grief, anger, sadness, guilt or shame. The truth is that parents are often struggling with big feelings of their own. Big feelings meeting big feelings is not an easy combination!

If we could somehow bring compassion into common parenting struggles we might shift how parents and children view their problems and how well they think they can cope. Because it’s not about our actual ability to cope, is it? It’s usually more about how we think we’ll cope in any given situation, which then affects our feelings and our responses. Not only does anxiety narrow our focus and make us overestimate the size of the problem at hand, it leads us to underestimate our ability to cope with that problem.

Naturally, parents who come into my clinic are looking for my perspective on what is happening with their child and suggestions on how to best help them. I find that teasing out how the parents feel in response to their child’s big feelings is usually the best first step.

Listening and being compassionate, parent to parent, is the best gift I can offer them. Naturally, I’ll have my opinion on their difficulties and have tools in my toolbox to share with parents, but the most important thing is to build a relationship so they feel more comfortable with the journey we’re embarking on together.

And that is why I’m using the compassionate approach as a foundation for supporting you in helping your anxious child. It provides the scaffolding needed to support you and your child to feel safe, connected and empowered.

Compassion-focused therapy and the Three Circles

Compassion reduces our fear, boosts our confidence, and opens us to inner strength. By reducing distrust, it opens us to others and brings us a sense of connections with them and a sense of purpose and meaning in life.

Dalai Lama

Compassion-focused therapy (CFT)16 pays particular attention to how our early childhood experiences have affected the types of emotions we have as adults. It’s especially useful for people who are particularly critical of themselves or who have high levels of shame, as well as people who have difficulty feeling warmth towards, and being kind to, themselves or others. For adults and children alike, these problems are often rooted in a difficult childhood in which the child may not have felt safe, loved or valued as much as they needed.

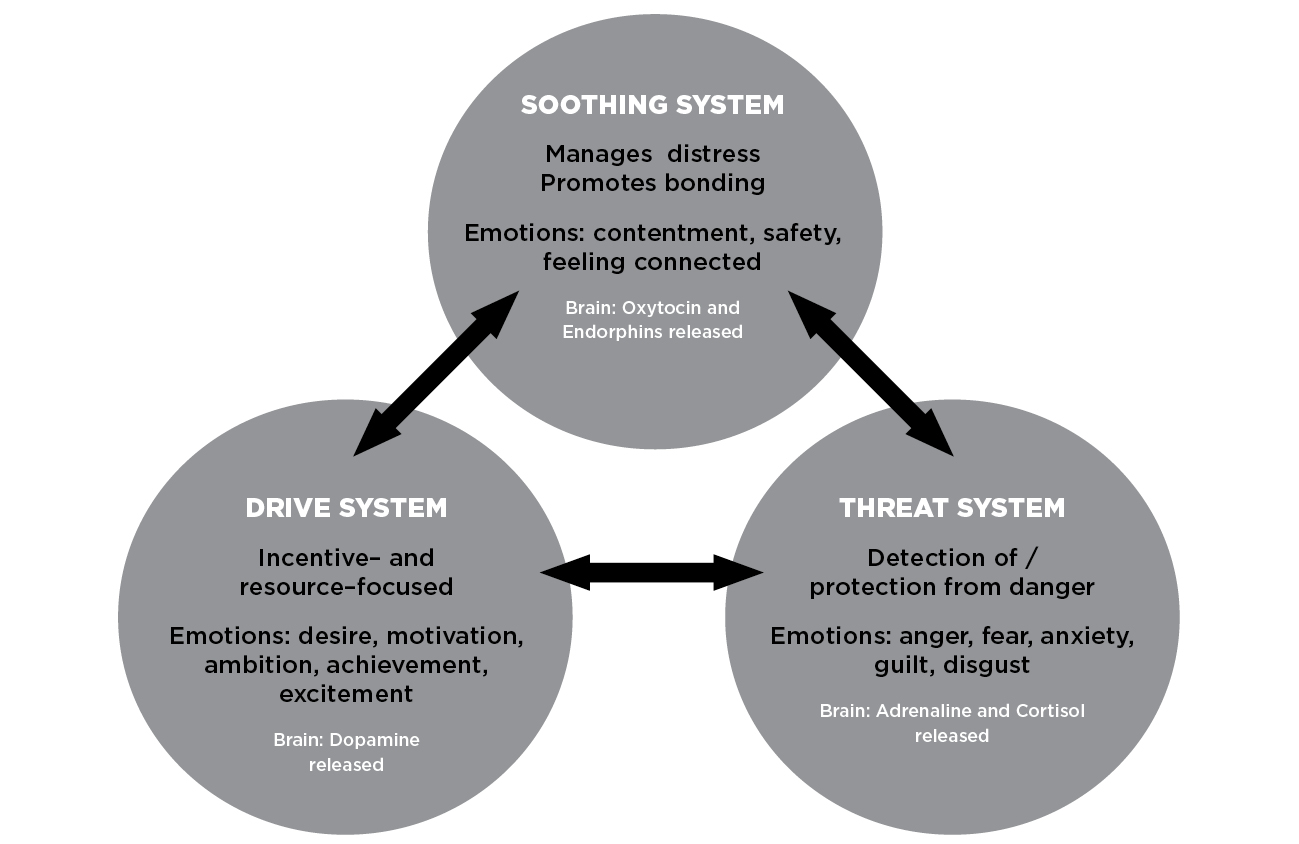

CFT deals with the ways that we learn to manage our emotions from childhood onwards. Research in neuroscience shows that humans have evolved at least three types of emotional regulation system – or Three Circles, as they’re known – that work together to control and maintain our emotions. These Three Circles help us to navigate and understand our emotional world and that of our children. Looking at these is helpful for both parents and children because they help to explain the guiding forces behind our reactions to the daily challenges we face.

If you look at the diagram,17 the three systems are:

The Threat system – helps us to detect and respond to threats in our lives. If the Threat system had a motto, it would be ‘better safe than sorry’. It’s commonly associated with anger, fear, anxiety, guilt, disgust and our inner self-critic.

The Drive system – enables us to go out and get what we need, and to take pleasure in doing it. It’s what helps to get you out of bed in the mornings, and is connected with desire, the thrill of the chase, achievement and excitement.

The Soothing system – helps to calm and nurture us and to balance the other two systems. It gives us positive feelings of peaceful well-being, safety, connection and contentment.

The diagram of the Three Circles shows how one system can dominate over another, with Threat often taking over while Soothing goes undernourished. Both the Threat and Soothing circles can feed into the Drive circle. The diagram helps you to understand which aspects of your life typically fit into each of the circles:

Threat: any major pressure in any area of your life – be it at work, in your relationships, among your family. Anything that threatens your sense of worth and safety.

Drive: anything that motivates you to get up in the morning, whether positive or negative.

Soothing: what you enjoy doing; passions; positive relationships; hobbies; what you do in your downtime. Whatever makes you feel safe.

By paying particular attention to whichever system is less active, we can learn to manage each system more effectively. Nurturing the underactive circle reduces symptoms such as low mood, anxiety and stress, and helps us to respond to everyday situations in an emotionally healthier way.

CFT focuses on the link between our thoughts, how we live our lives and our Three Circles. Through activities like attention training and mindfulness, compassionate skills are cultivated to help clients notice how their minds can be taken over by negative emotions and to nurture their relationship with themselves and with others.

CFT is a wonderful therapy for managing many mental health and emotional issues. This is particularly true for stress and anxiety, which occur when the body’s Threat and Drive systems are going hell for leather at the expense of an underactive Soothing system. Indeed the modern-world experience of toxic stress may have its origins in not feeling good enough in childhood, which manifests in later life as a greatly reduced Soothing circle, triggering a Threat reaction related to the fear of rejection or abandonment.18>

CFT helps people to develop the resources to deal with difficult emotions. The beauty of it is that it enables them to disclose deeper feelings, such as unworthiness and shame, which other psychological therapies can have a hard time targeting. Handling such feelings productively prevents us from compensating with behaviours such as working, eating or exercising to excess, or resorting to drugs or alcohol.

The three qualities of self-compassion

We have already caught glimpses of how useful self-compassion can be in approaching anxiety in children and adults. Derived from pioneering psychological research,19 the three central qualities of self-compassion are self-kindness, our shared human experience and mindfulness, which combine and interact to improve our state of mind. Below is a list that compares these three qualities to their opposites, showing how much more useful self-compassion is for helping us and our children with the challenges we all face:

Self-kindness versus self-judgement: Working on being kind to yourself and less judgemental is easier said than done, isn’t it? In building our emotional reserves as parents, we need to be more accepting of our own limits, and learn to step away from negative feelings about ourselves. In being a little kinder to ourselves, we’ll be calmer, more balanced and better able to care for ourselves and our children.

Common humanity versus isolation: If we feel that we’re the only person struggling with a particular problem, we’ll end up feeling isolated. But if we recognise that suffering, relationship troubles and mistakes are part of being human, we’re far more likely to open ourselves up to connecting with other people, to forgive ourselves and others, and to get back up and try again!

Mindfulness versus over-identification: Those who suffer with anxiety often focus on the past and the future, and feel both weighing heavily upon them. Mindfulness is a powerful tool for both children and their parents in navigating the storms of anxiety. When we accept our emotions rather than judge ourselves for being emotional, our emotions tend to run their natural and relatively short-lived course.20

The healing balm of self-compassion

When we soothe our painful feelings with the healing balm of self-compassion, not only are we changing our mental and emotional experience, we’re also changing our body chemistry.21

By tapping into our body’s self-healing Soothing system we trigger the release of oxytocin. Known as ‘the hormone of love’, and particularly associated with first cuddles between parents and newborns, this chemical helps us to feel safe, calm and securely connected with others. Oxytocin is responsible for fine-tuning our brain’s social instincts and making us do things to strengthen close relationships.

Oxytocin is released in a variety of social situations, from when a baby is first held, to when parents joyfully interact with their children, to when someone you really love gives you a hug – when released it makes you more likely to feel warmth and compassion for yourself and empathy towards others.

Because thoughts and emotions have the same impact on our bodies irrespective of whether they’re directed towards ourselves or others, self-compassion is a powerful trigger for the release of oxytocin.22

But wait for it: our dear friend oxytocin is actually a stress hormone that your pituitary gland pumps out as part of your biological stress response. Just as the stress hormone cortisol is released to spur you into immediate action and adrenaline is released to make your heart pound, oxytocin is released in response to a perceived threat so you notice when someone close is struggling or to motivate you to seek support and be surrounded by those who care about you. Amazing isn’t it?

In her groundbreaking book The Upside of Stress and her TED talk ‘How to make stress your friend’,23 health psychologist Kelly McGonigal talks about the impact of our beliefs about stress on our overall health. According to McGonigal, our bodies have a built-in mechanism to help us cope with stress: the human connection.

Stress gives us access to our hearts. The compassionate heart that finds joy and meaning in connecting with others, and yes, your pounding physical heart, working so hard to give you strength and energy, and when you choose to view stress in this way, you’re not just getting better at stress, you’re actually making a pretty profound statement. You’re saying that you can trust yourself to handle life’s challenges, and you’re remembering that you don’t have to face them alone.

McGonigal supports the idea that the quality and power of our Soothing systems are strongly associated with the bonds we form with others from early childhood onwards, a concept that’s also central to attachment theory.24 In human beings, the first and most powerful bond an infant is programmed to make is usually with their mother or father. This attachment serves to improve the baby’s chance of survival (think food, comfort and our most basic needs) when faced with a threat, brings a sense of mutual connection and well-being, and builds the foundation for virtually every aspect of the child’s development.

Talking about attachment and childhood can trigger painful memories and thoughts for many parents, myself included. Please be mindful of this as you read this book and gain support from close loved ones – or a professional – if you’re struggling. You may not have expected to go so deep, but as my own counsellor told me after a tough session, ‘Once you hit the bottom of the pool, you can only bounce back up.’

Galway City Early Years Committee and the Galway Parent Network ran a poster campaign that was based on this idea called ‘How to build a happy baby’ as part of an infant mental health initiative. We don’t often think of the mental health of babies, but it refers to a child’s social and emotional development from birth to age three within the context of their relationship with the most important person in their lives.

Based on the UNICEF and the World Health Organization (WHO) Baby Friendly Health Initiative,25 we created four posters containing simple, positively framed, evidence-based messages emphasising the innate abilities of human beings to look after their babies. The purpose of the posters was to promote the importance of the child–parent attachment and to dispel common parenting myths.26 One read:

New babies have a strong need to be close to their parents, as this helps them to feel secure and loved, like they matter in the world.

Myth: Babies become spoilt and demanding if they’re given too much attention.

Truth: When babies’ needs for love and comfort are met, they’ll be calmer and grow up to be more confident.

Evidence: Close skin-to-skin body contact, postnatally and beyond, significantly improves the physical and mental health and well-being for both mother and baby. When babies feel secure, they release a hormone called oxytocin, which acts like a fertiliser for their growing brain, helping them to be happier and more confident as they grow older. Holding, smiling and talking to your baby also releases oxytocin in you, which also has a soothing effect.27

Crucially, the child–parent attachment bond that we all see in babies remains strong for child and parent as they grow older. The first three years of life, when a child’s brain develops the fastest, are a critical window of opportunity for establishing a healthy stress response, although it’s never too late to help your child to manage their distress.

Soothing your child during their stressful or anxious moments releases oxytocin in both of you, giving child and parent a sense of security and helping you to become more resilient, knowing that your bond with each other is strong. When you tune in to your child’s feelings and help them to calm down, you also play a significant role in easing their fears and their fight-flight-freeze cortisol levels.

A parent’s compassionate response to their child during their anxious moments has the power to deactivate their Threat system and activate their Soothing system. The calmer and safer a child feels, the more open and flexible they’ll be in response to their environments and the more likely they’ll be able to use the tools to evaluate and manage future threats.

Relationships like the one you share with your child work to transform ‘stress and anxiety into catalysts for courage and connection’.28 While anxiety is certainly not a pleasant experience for anyone, it might help to know that your child has a naturally strong desire to connect with you during their most anxious moments, even though it may not always appear that way.