Полная версия

How to Draw a Map

Eratosthenes had come pretty close to the correct answer, based on the tools and geographic knowledge available to him. There were mistakes: the earth is not a perfect sphere; Syene is not exactly on the tropic of Cancer (it is 60 kilometres north) and is not on the same meridian (it is 3 degrees 3 minutes east). However, Eratosthenes had established some of the elementary rules in cartography and, for many mapmakers that would follow, the importance of astronomy in calculating your bearings on earth.

During his lifetime, Eratosthenes’ researches covered many fields – his colleagues nicknamed him ‘Beta’ because he covered so much that he always came second (Beta is the second letter of the Greek alphabet). Perhaps there was a hint of jealousy on their part. Other admirers called him Pentathlos after the Olympian athletes who were all-rounders and capable competitors.

In old age, Eratosthenes contracted ophthalmia and became blind, leaving him no longer able to read the scrolls in the Great Library or to observe nature and the heavens. Frustrated, he chose to starve himself to death, dying in 194 BCE aged 82, probably in his beloved library.

* The Greek Heliocentric Theory.

3

THE LEGACY OF ROME

The Greeks had made unparalleled progress in the theories of cosmology and geography. The Romans, however, though heavily influenced by Greek theories, were principally concerned with the practical applications of mapmaking. These were adapted and taken into the service of the Roman state and its empire, whether for planning campaigns or travel, administering trade, establishing new colonies or, if possible, superimposing some sort of standard grid so that Rome’s expanding possessions could be planned and understood as an interconnected whole – and, of course, exploited (or as we now say, taxed). As the Roman author Strabo said:

Political philosophy deals chiefly with the rulers, and if geography supplies the needs of those rulers to govern then geography would seem to have some advantage over political science.

Strabo (64 BCE–24 CE) was born in Amaseia, Asia Minor, to wealthy parents who had been movers and shakers in the administration of King Mithridates VI of Pontus. Strabo was Greek by language and learning, and pro-Roman by political inclination. That was probably the right view for a family wanting to hang on to its wealth, since Pontus had recently fallen into the hands of the Roman Republic. In Strabo’s lifetime, Rome would extend its control in the region. Strabo was educated in Caria in the city of Nysa under the rhetorician Aristodemus, a teacher who also educated the sons of the Roman general who took over Pontus and, perhaps later, may have known or been influenced by the polymath Posidonius (135–31 BCE). He certainly referred to his work in his later description of Gaul and its Celtic inhabitants.

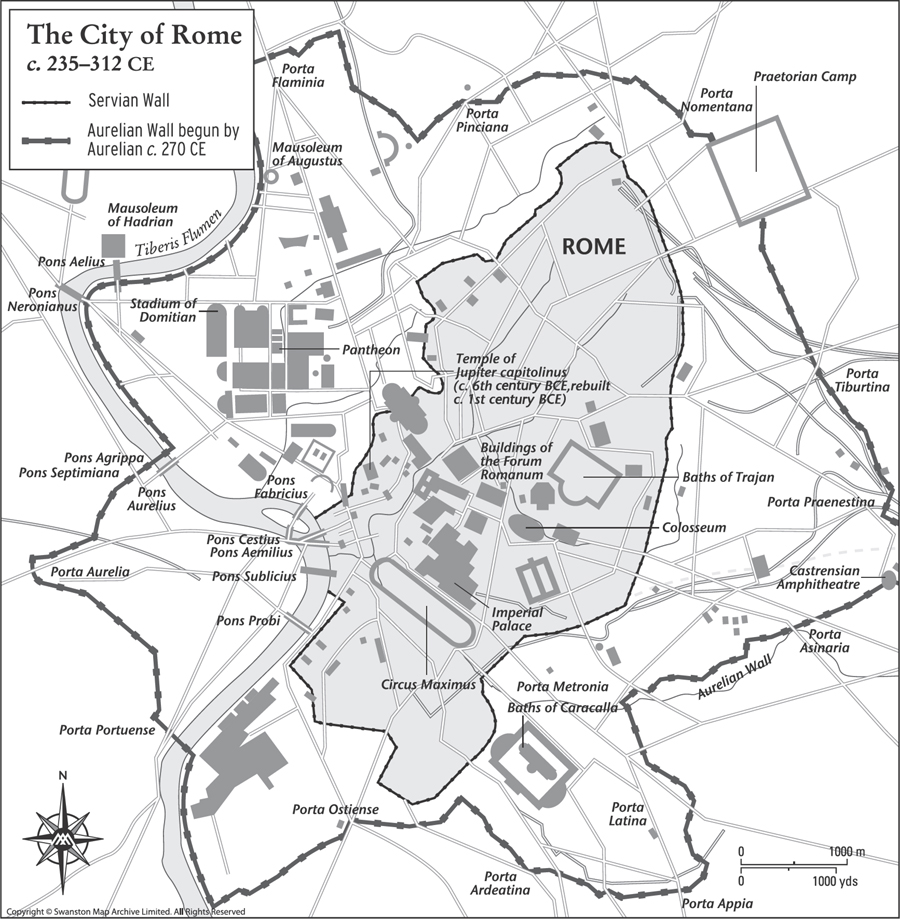

Map 7. The Servian and Aurelian walls were built to protect the city of Rome, which was becoming increasingly vulnerable to attacks from Germanic tribes in the 3rd century CE.

At about 21 years old, Strabo moved to Rome where he continued his studies under the peripatetic Xenarchus. He studied grammar under the famous Tyrannon of Amisus, also in Pontus, a much-respected authority on geography, and a final influential mentor was Athenodorus Canamotes, a philosopher, originally from near Tarsus, who moved to Rome in 44 BCE where he ingratiated himself with the Roman elite. As well as instructing Strabo, he passed on his contacts in the Roman power structure.

With such an education, contacts and considerable help from the bank of Mum and Dad, Strabo was able to travel and indulge his enquiring mind. He wrote his modestly titled Historical Notes, which in fact was a huge undertaking in 43 volumes that, alas, is now lost. However, his Geographica (‘Geography’), an encyclopaedia of geographical knowledge in 17 volumes, survives – that is, almost survives; part of the end of Volume Seven is lost.

During his time in Rome, Strabo witnessed the end of the Republic, a form of government that had existed for around 480 years. The change dated from 27 BCE when the Roman Senate granted extraordinary power to Gaius Octavius and Marcus Agrippa, great-nephews of the assassinated Julius Caesar (44 BCE). Gaius Octavius adopted the title Augustus and managed to bring peace and stability to what was now the Empire. By now Strabo had returned to Asia Minor, but he was back in Rome by 29 BCE to see the new emperor assume his full power.

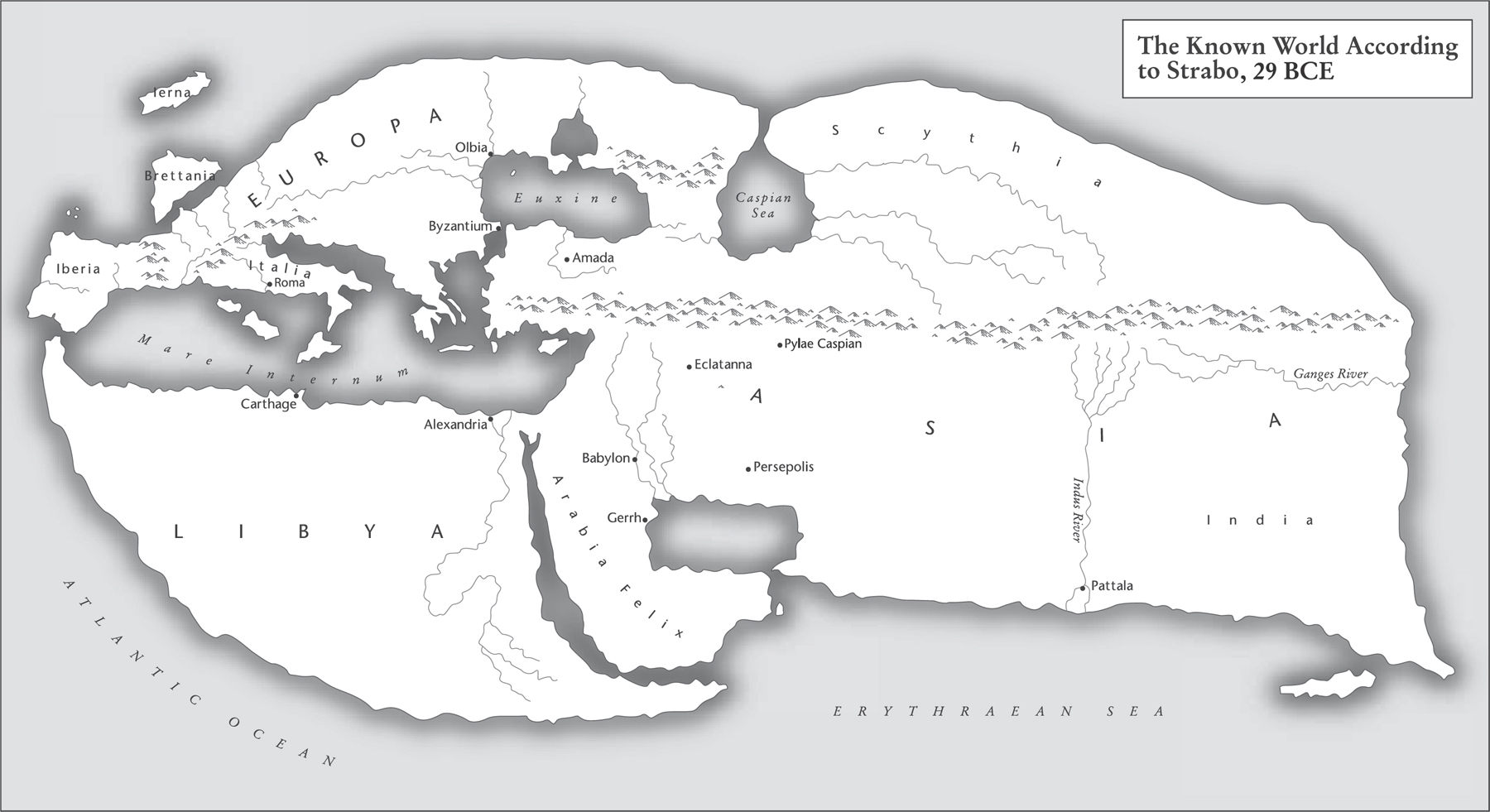

Map 8. Strabo was pro-Roman by politics and Greek by culture. His concept of the world was influenced by Eratosthenes and other Greeks.

In 29 BCE Strabo travelled from Rome to Alexandria in Egypt in the company of his influential friend Aelius Gallus, Prefect of Egypt. Even travelling first class in a well-built galley, this would take around 21 days. Gallus toured his province of Egypt accompanied by Strabo, and part of his mission to the east was to take an expedition to Arabia, an area that was presumed, at least by the Romans, to be full of all kinds of treasures. The purpose of the expedition was to conclude a number of friendship treaties with the local peoples, which of course was intended to benefit Rome. However, the expedition was a failure; after some initial success, there followed a long march to the south through endless deserts, leading to a brief siege of Ma’rib, capital of the Kingdom of Saba. Meanwhile, the accompanying Roman fleet destroyed the port of Aden. All these efforts came to naught after Gallus lost the bulk of his army. Originally 10,000 strong, the weary, sun-scorched survivors retreated to Egypt. The emperor recalled Gallus back to Rome, in some disgrace, but Strabo stayed in Egypt and spent at least some time in the Great Library at Alexandria, the old haunt of Eratosthenes.

Strabo returned to Rome in around 20 BCE, now a Roman citizen, and there settled into writing. He began his surviving work, Geographica (‘Geography’), the first edition of which was published in 7 CE, far from Rome for some reason. The work was consequently unknown in Rome but widely read in the Romanised east, and maybe that was Strabo’s intention, his pro-Roman legacy. After a long gap, there was a second edition in 23 CE, but this was the last year of Strabo’s life. He was now back in his home town of Amaseia, and died aged 87, having achieved perhaps the first attempt to assemble the best available geographical knowledge into a single work, which would go on to influence the work of many others.

PTOLEMY

Claudius Ptolemy was probably born in Alexandria around 100 CE. Despite his family name, he was not related to the Egyptian royal family, the founders and protectors of the Great Library. It was in this city, some 400 years after its foundation, that Ptolemy created his masterwork, Geographite hyphegesis (‘Guide to Geography’), as it was later known among its readership.

The Great Library at Alexandria, dedicated to the Nine Muses of the Arts, had been destroyed some 148 years before Ptolemy’s birth during Caesar’s Civil War in 48 BCE, when his forces were threatened by the Egyptian navy. During attempts to destroy that threat, Caesar’s own ships were burnt and, according to some descriptions, the resulting conflagration spread to the Great Library, destroying much of its invaluable contents.

Ptolemy sat among the patched-up halls of the library compiling his Geography in around 150 CE. Much of his writing relied on earlier work, especially that of Marinus of Tyre (70–130 CE). His study was written in Greek – as were most of its precursors – on a papyrus roll over eight sections or ‘books’, and in it he reviewed the combined total research of the classical world to date. The outcome of this monumental work was to define mapmaking, at least in the West, for the next 2,000 years.

Ptolemy regarded himself firstly as a mathematician, astronomer and philosopher. He did not refer to himself as a geographer. Indeed, the Greek spoken by Ptolemy had no word for geography. What we call a map, he called a pinax, or he may have used the phrase periodos ges, a ‘circuit of the earth’. In time, these terms would be replaced by the Latin mappa.

Ptolemy had established his credentials, first in astronomy, writing a work called Ho megas astronomos (‘The Mathematical Collection’), later known as the Almagest (Arab astronomers used the Greek superlative term Megiste for this work, and when the definite article in Arabic, ‘al’, was prefixed it became Almagest).

The Almagest’s 13 books deal in detail with astronomical concepts, the stars, the solar system and other observable objects. In them, Ptolemy produced his geocentric theory that placed the earth at the centre of the universe, often known as the Ptolemaic Cosmology, and this view was held by the majority of observers and thinkers until the heliocentric, sun-centred theory developed by Copernicus 1,300 years later.

In the Almagest Ptolemy wrote:

I know that I am mortal by nature, and ephemeral; but when I trace at my pleasure the windings to and fro of the heavenly bodies, I no longer touch earth with my feet, I stand in the presence of Zeus himself and take my fill of ambrosia.

He obviously felt some passion for his work. Now we come to Ptolemy’s Geography. He approached this work by first gathering the learning from the Babylonian, Greek, Roman and Persian worlds and applying this accumulated knowledge into a mathematical framework.

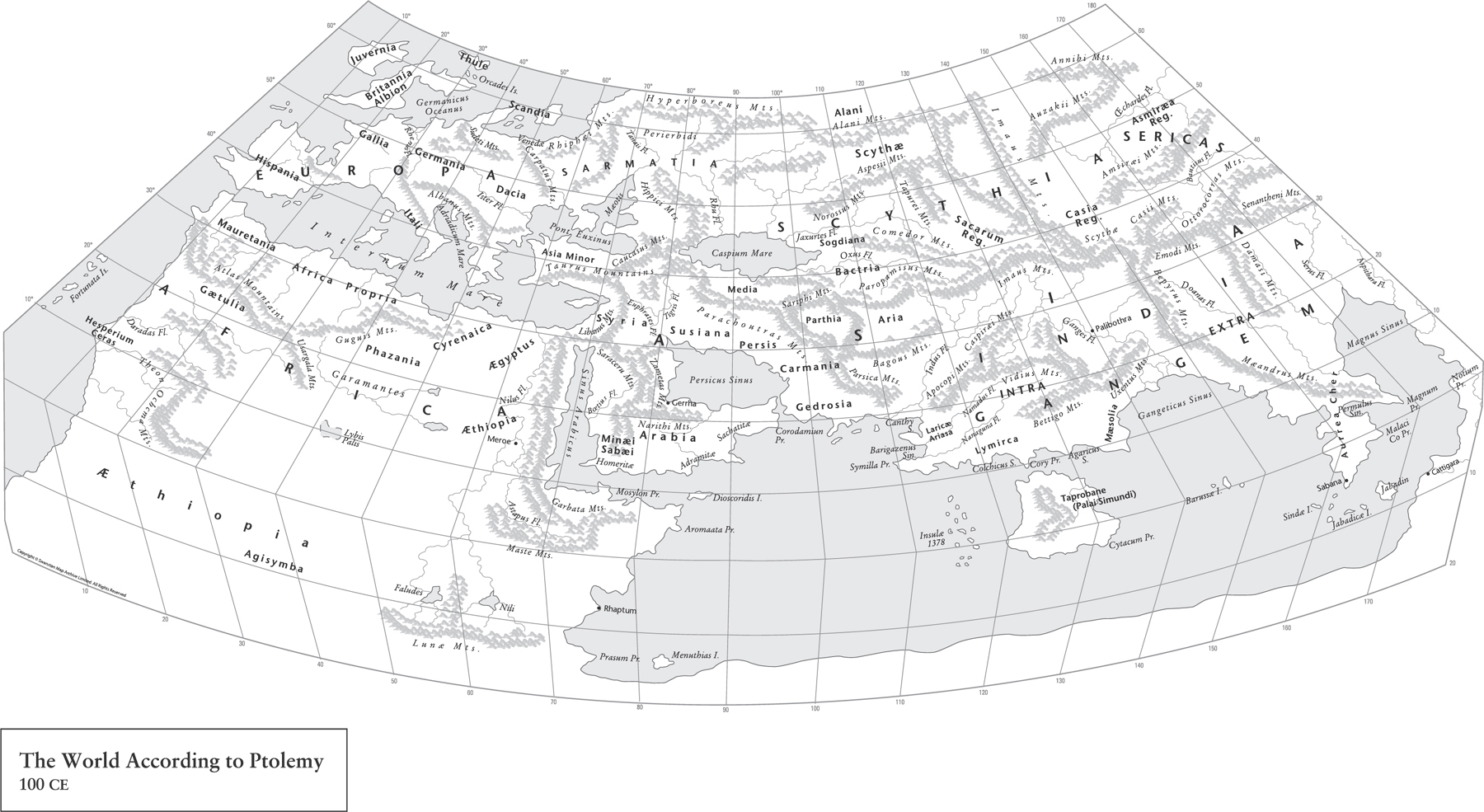

A large part of Book 1 describes how to draw the maps using his ‘projection’ – his coordinates are in degrees: 360 to complete the circle, 60 minutes to a degree, just as we still use. His east–west longitudes are measured eastwards beginning with 0 degrees at a point just west of the Canary Islands, known to him as the ‘Blessed Isles’. The north–south latitudes are measured heading north from the equator, again like our own today. He did, however, mark his degree sign with an asterisk: 10*, not 10° as we now use.

His skill was in devising this mathematical formula that allows the rendering of the earth’s sphere onto a flat surface. This was an improvement on past ‘world’ map projections, given that all maps are some kind of compromise when rendering a sphere onto a flat sheet of papyrus or paper. He also placed north at the top, an orientation once again familiar today. This was the first example of a conical map projection. Ptolemy had succeeded in providing a simple, reliable method of drawing a world map.

The complete text drew on all the works available to Ptolemy in Alexandria, such as Tacitus with his descriptions of Gaul. Ptolemy laid down rules for mapping local features such as cities, harbours and farms. He stressed the importance of astronomy and mathematics to geography, creating a system based on the unchanging features of the sun and the stars, and demanding that longitude and latitude be used to fix locations of geographical features: mountains, estuaries, settlements, etc. By adhering to this system, mapmakers ensured their maps were accurate and could be systematically reproduced. That is, of course, as long as the information supplied was accurate – a problem the modern mapmaker still encounters.

The completed text of Geography is more than a list of geographical coordinates. Ptolemy chose to review and carefully analyse the descriptions available to him, then selected the most reliable, but he still left a warning as to the reliability of some descriptions. The mapmaker is only as good as the information he has to hand. This gazetteer was eventually to list some 8,000 locations, according to their latitude and longitude, beginning in the west with the British Isles, moving eastwards across Europe towards Asia Minor and ending with India in the east, his known world. It is not known if Ptolemy produced maps himself to go with his geographic gazetteer; if he did, none have survived.

Ptolemy divided the globe’s circumference into 360 degrees (the Babylonian sexagismal system); every degree was measured in units of 60. He estimated each degree at 500 stades (2,700 kilometres), a total of 180,000 stades. He envisaged his world as smaller than Eratosthenes’ calculations; however, he did argue that the world’s inhabited regions were larger than many believed, reaching from the Fortunate Isles in the west to Cattiagara in the east, believed to be somewhere in modern north Vietnam. From north to south was measured at 40,000 stades from Thule at 63 degrees north to Agisymta in sub-Saharan Africa at 16 degrees south. Ptolemy’s world had blurred edges based on theories, stories and guesswork. For instance, he believed that a large, unknown continent existed in the southern hemisphere in order to balance Europe and Asia in the northern hemisphere and that the Indian Ocean was enclosed by Africa, extending eastwards to join up with Asia. This last feature appeared on Ptolemaic maps even after the Portuguese had sailed around Africa into the Indian Ocean.

After Ptolemy’s time, whatever was left of the Great Library of Alexandria was lost through invasion and war, a fact that haunts the enquiring mind to this day. However, some works survived and Geography was one of them. The earliest known copy of Geography that exists is in Arabic and dates from the 12th century, preserved by Islamic scholars who reintroduced it into Europe, where it was translated from Arabic into Byzantine Greek in the 13th century and then into Latin in the 15th century. The work made it into print in 1475. The Ulm edition, printed in 1482 in Germany, included woodcut maps of new discoveries like Greenland, which was placed using the Ptolemaic principles of its longitude and latitude. Now, 1,300 years after his death, Ptolemy was a bestseller as his books poured off the printing presses.

Map 9. Ptolemy’s maps were the first to use longitudinal and latitudinal lines as well as specifying terrestrial locations by celestial observations.

Ptolemy’s mathematical scientific system made the chaotic world understandable by the application of methodical geometric order. Thousands of descriptions made by sailors, travellers and generals, with all their sense of wonder at the almost endless diversity of landscapes and peoples, came together as an understandable whole. Ptolemy’s achievement lasted into and past the Renaissance. I still plot my maps in degrees and minutes. I still check gazetteers of verified locations – now online, of course.

These things belong to the loftiest and loveliest of intellectual pursuits, namely to exhibit to human understanding through mathematics both the heavens themselves in their physical nature (since they can be seen in their revolution about us), and the nature of the earth through a portrait (since the real earth, being enormous and not surrounding us, cannot be inspected by any one person either as a whole or part by part).

Ptolemy’s Geography, Book I

The classical world in which this achievement was created, though, was now under threat.

4

THE ROAD TO PARADISE

By the beginning of the 4th century CE, the empire in the West was perhaps less ‘Roman’: many of its provinces were in the ownership of federated tribes – semi-independent kingdoms concerned with their own politics. The Roman state was a less cohesive entity. In the East, Alexandria, still a centre of learning, though much reduced, also became a centre of revolt. The museum buildings, by now over 500 years old and not in the best of condition, were finally destroyed, though the Great Library building still survived. In 391 CE, the library finally met its end when a Christian mob broke in, burned the almost irreplaceable contents and turned the building into a church, a triumph of faith over reason.

Meanwhile, a few years earlier at the opposite end of the empire along Hadrian’s Wall in Britannia, Magnus Maximus, who was commander of Britain, withdrew troops from northern and western Britain in pursuit of his own ambitions for imperial rule, usurping power from Emperor Gratian. His attempts ultimately failed, being defeated by Emperor Theodosius, and Maximus was finally executed in 388. With his death, Britannia came back under the direct rule of Theodosius, that is until 392 when another usurper, Flavius Eugenius, made another bid for imperial power. Again, after just two years his short-lived rule over the West failed when Theodosius marched from Constantinople at the head of his army and defeated Eugenius at the Battle of Frigidus in September 394. Eugenius was captured and executed as a criminal. The following year, 395, the victorious Theodosius died, leaving his 10-year-old son Honorus as Emperor in the West. However, the real power in the West was in the hands of Flavius Stilicho, a highly experienced general who had risen through the ranks. In 402 it was his decision to finally strip Hadrian’s Wall of its remaining garrison, and possibly other troops in Britain, to face wars with the Ostrogoths and Visigoths on the Continent.

Meanwhile, the Romano-Britons now dispensed with imperial authority. In 407, they selected Flavius Claudius Constantinus, or Constantine III, as their leader, who now declared himself the Western Roman Emperor, gathered the last Roman troops in Britain and headed for Gaul. Sixty-six years later, in the West, Rome was gone, replaced by a collection of ‘Barbarian’ kingdoms. The new kingdoms lived among the remains of a once great empire. The skills needed to repair and maintain roads, bridges, aqueducts and great buildings were lost. The Anglo-Saxon poem The Ruin, written by an unknown author, looks upon the moss-covered buildings with a sense of wonder:

Wondrous is this wall-stead, wasted by fate.

Battlements broken, giant’s work shattered.

Roofs are in ruin, towers destroyed,

broken the barred gate, rime on the plaster,

walls gape, torn up, destroyed,

consumed by age, Earth-grip holds

the proud builders, departed, long lost,

and the hard grasp of the grave, until a hundred generations

of people have passed. Often this wall outlasted,

hoary with lichen, red-stained, withstanding the storm,

one region after another; the high arch has now fallen.

The wall-stone still stands, hacked by weapons,

by grim-ground files.

Along with Roman infrastructure, the written word, the scrolls of study, were largely lost, at least in the West. As the natural science of the Greeks and Romans faded and almost disappeared, some ‘stories’ written in the 3rd century survived and became part of the early medieval world view. One such work was the product of Caius Julius Solinus, whose speciality was the study of grammar. His book A Collection of Memorable Facts comprises 1,100 descriptions that range from direct biblical descriptions to tall tales of Africa where the shadows of hyenas robbed dogs of their ability to bark. It was a great collection of myths – exaggerated travellers’ tales borrowed from many previous authors, with just enough geographical reality to give this masterpiece of disinformation a kind of believable life of its own. In the 6th century it was revised and republished under the title Polyhistor, meaning ‘many stories’.

The Christian faith spread around the Mediterranean from its place of origin in Palestine. It was a religion that, in a changing world occupied by usurpers, barbarian invaders, plagues and famine, offered at least the promise of a better life in the next world – the afterlife. The prevailing Greco-Roman religion did not offer any of that – it demanded sacrifice. The cults offered no guidance for the living of a good life; the underworld was not a place of peaceful eternity.

The Christian world still had a place for the Devil and leagues of demons. By the Edict of Thessalonica, 380 CE, Christianity was confirmed as the religion of the Roman Empire. Now, with official sanction, the new faith began its work: the suppression of pagan beliefs. Unfortunately, most of Greco-Roman scientific research was included in the works that were destroyed or suppressed. The Academy School of Philosophy, which had roots going back to 387 BCE, finally closed its doors in 528 CE, after 916 years of considered thought (though with interruptions), its teachers chased away, hunted down as pagans. The new religion destroyed far more than it saved, but in all this chaos, a new world view evolved that was based on faith. This would change the mapmakers’ approach to representing the world – at least for a few hundred years.

Sebastian Munster (1448–1552) was a theologian and Hebrew scholar who taught at the University of Heidelberg. Like many learned people of his age, he also had an interest in geography and mapmaking. He produced two major works: the first, in 1540, was Ptolemy’s Geography with 48 woodcut maps. He carved the names of places, cities and states on removable blocks, which enabled the map to be changed and updated without recarving the entire map. His next cartographic work was Cosmography, published in 1544, in which he mapped each continent separately and listed the sources upon which his maps were compiled. Moreover, the blank spaces were ‘decorated’ with strange fictional races and creatures that featured on the maps of Solinus. These went on to be copied onto maps produced up until the 18th century.

The disinformation spread by the works of Solinus had already been compounded by ‘Christian geography’; one such work was written in the 500s by Cosmas Indicopleustes, who believed that all things – the nature of the universe, all living things and the form of the earth – could be found in the Holy Scriptures.

In his earlier life, Cosmas had been a successful merchant trading over much of the known world, around the cities of the Mediterranean and as far east as Ceylon (Sri Lanka). He converted to Christianity and eventually settled into the cloistered life of a monk, retiring to a monastery in the Sinai desert. He produced a work called Christian Topography, in which he looked only to the scriptures, describing the world as a flat parallelogram, with Jerusalem at its centre. It was written in Ezekiel 5.5: ‘I have set Jerusalem in the midst of the nations and countries that are round about her.’ Cosmas argued that in the far north of the inhabited world there was a great mountain around which the sun and moon revolved, creating night and day. Beyond the centre lay a great ocean, and beyond that were other lands where, before the biblical flood, people lived but that were now uninhabited and inaccessible. Beyond these empty lands arose the four walls of the sky meeting in the dome of heaven, the ceiling of the tabernacle. In his Christian Topography, Cosmas berates arrogant and sceptical scholars who:

attribute to the heavens a spherical figure and a circular motion, and by geometrical method and calculations applied to the heavenly bodies, as well as by the abuse of words and by worldly craft, endeavour to grasp the position and figure of the world by means of the solar and lunar eclipses, leading others into error, while they are in error themselves, in maintaining that such phenomena could not represent themselves if the figure was other than spherical.

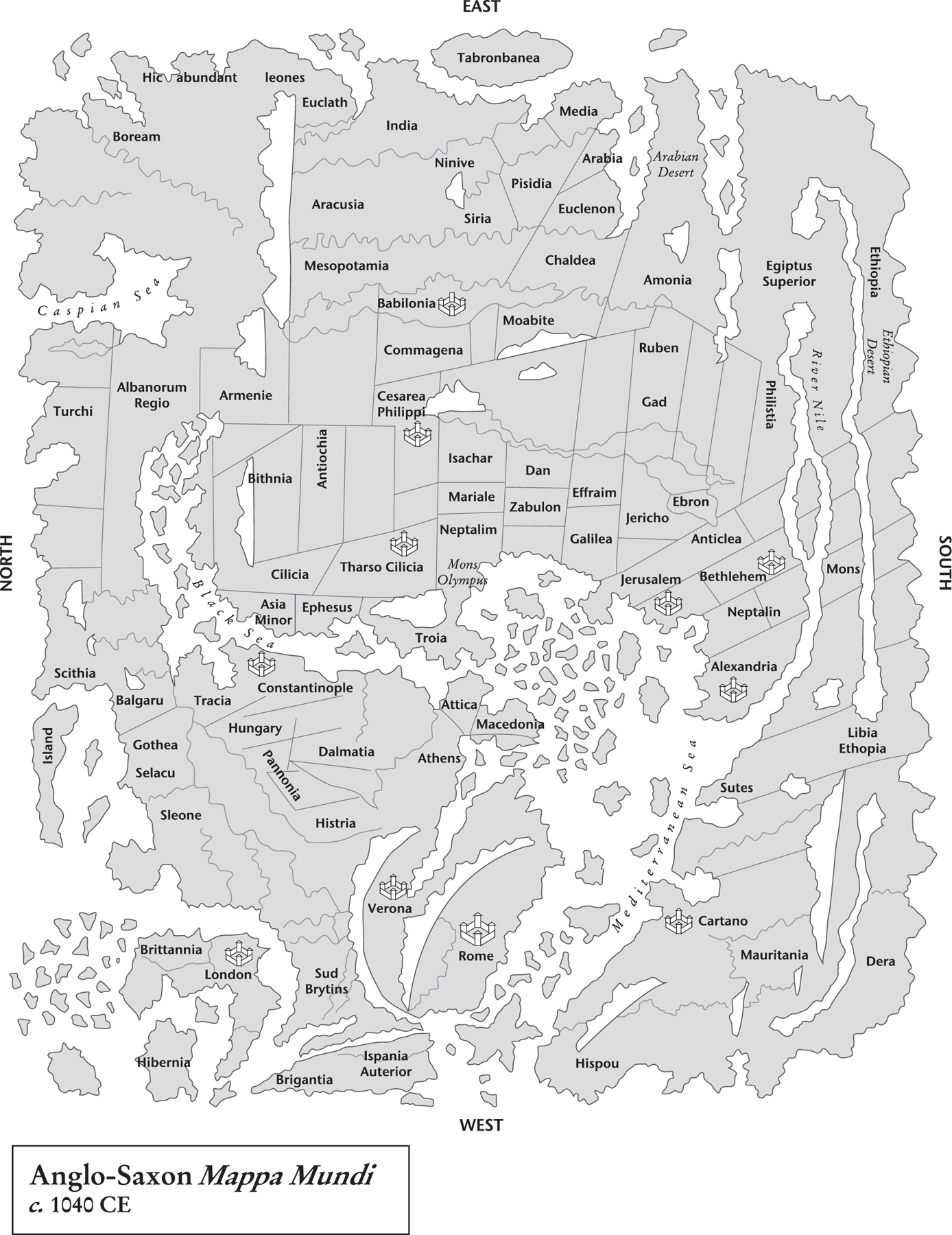

Map 10. The original of this map was created in around 1040 and contains the earliest-known vaguely realistic depiction of the British Isles.