Полная версия

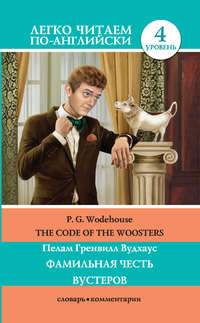

The Code of the Woosters / Фамильная честь Вустеров

Пелам Гренвилл Вудхаус

Фамильная честь Вустеров / The Code of the Woosters

Адаптация текста и словарь С. А. Матвеева

Pelham Grenville Wodehouse

THE CODE OF THE WOOSTERS

© The Trustees of the P.G. Wodehouse Estate

© Матвеев С. А., адаптация текста, словарь, 2018

© ООО «Издательство АСТ», 2018

One

“I reached out a hand from under the blankets, and rang the bell for Jeeves. “Good evening, Jeeves[1].”

“Good morning, sir.”

This surprised me. “Is it morning?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Are you sure? It seems very dark outside.”

“There is a fog, sir. We are now in autumn—season of mists and mellow fruitfulness[2].”

“Season of what?”

“Mists, sir, and mellow fruitfulness.”

“Oh? Yes, I see. Well, get me one of those cocktails of yours, will you?”

“I have one in the fridge.”

He shimmered out, and I sat up in bed feeling I was going to die in about five minutes. On the previous night, I had given a little dinner to Gussie Fink-Nottle[3] who was going to marry Madeline[4], only daughter of Sir Watkyn Bassett[5]. Indeed, just before Jeeves came in, I had been dreaming that some bounder was driving spikes through my head—not just ordinary spikes, but red-hot[6] ones.

Jeeves returned with his morning reviver. After drinking it, my skull flew up to the ceiling and the eyes shot out of their sockets and rebounded from the opposite wall like racquet balls. I felt better.

“Ha!” I said, retrieving the eyeballs and replacing them in position. “Well, Jeeves, what goes on in the great world? Is that the paper you have there?”

“No, sir. It is some literature from the Travel Bureau. I thought that you might care to glance at it.”

“Oh?” I said. “You did, did you?”

And there was a brief and—if that’s the word I want—pregnant silence. I suppose that when two men of iron live in close association with one another, there are occasional clashes. Jeeves was trying to get me to go on a Round-The-World cruise, and I would have none of it. But in spite of my firm statements to this effect, scarcely a day passed without him bringing me those illustrated folders which the travel agents usually send out. Jeeves was like some assiduous hound who will persist in laying a dead rat on the drawing-room carpet.

“Jeeves,” I said, “this nuisance must now cease.”

“Travel is highly educational, sir.”

“No more education. I was full up years ago. No, Jeeves, I know what’s the matter with you. That old Viking blood of yours! You yearn for the tang of the salt breezes. You see yourself walking the deck in a yachting cap. Possibly someone has been telling you about the Dancing Girls of Bali. I understand, and I sympathize. But not for me. I refuse.”

“Very good, sir.[7]”

He spoke with a certain what-is-it in his voice, so I tactfully changed the subject.

“Well, Jeeves, it was quite a satisfactory binge last night.”

“Indeed, sir?”

“Oh, most. An excellent time was had by all. Gussie sent his regards.”

“I appreciate the kind thought, sir. I trust Mr. Fink-Nottle was in good spirits?”

“Extraordinarily good, considering that he will shortly have Sir Watkyn Bassett for a father-in-law. Sooner him than me[8], Jeeves, sooner him than me.”

I spoke with strong feeling, and I’ll tell you why. A few months before, while celebrating Boat Race[9] night, I had fallen into the clutches of the Law for trying to separate a policeman from his helmet, and I had been fined. A fiver[10]! The magistrate who had inflicted this monstrous sentence was none other than old Bassett, father of Gussie’s bride-to-be.

I was one of his last clients, for a couple of weeks later he inherited a pot of money from a distant relative and retired to the country. That, at least, was the story. My own view was that he had got the stuff by sticking like glue to the fines. Five quid here, five quid there—a lot of money, eh?

“You have not forgotten that man of wrath, Jeeves? Eh?”

“Possibly Sir Watkyn is less formidable in private life, sir.”

“I doubt it. A hellhound is always a hellhound. But enough of this Bassett. Any letters today?”

“No, sir.”

“Telephone communications?”

“One, sir. From Mrs Travers[11].”

“Aunt Dahlia[12]? She’s back in town, then?”

“Yes, sir. She expressed a desire that you would ring her up at your earliest convenience.”

“I will do even better,” I said cordially. “I will call in person.[13]”

And half an hour later I was near the steps of her residence. I did not know that I was to become involved in an imbroglio that would test the Wooster soul as it had seldom been tested before. The story was connected with Gussie Fink-Nottle, Madeline Bassett, old Pop Bassett, Stiffy Byng[14], the Rev. H. P. (“Stinker”) Pinker[15], the eighteenth-century cow-creamer[16] and the small, brown, leather-covered notebook.

* * *But I was looking forward with bright anticipation to the coming reunion with Dahlia—she, being my good and deserving aunt, not to be confused with Aunt Agatha[17], who eats broken bottles and wears barbed wire[18] next to the skin. Apart from the mere intellectual pleasure of talking to her, there was the prospect that I might be able to get an invitation to lunch. Anatole[19], her French cook, was outstanding!

The door of the morning room was open. Aunt Dahlia greeted me:

“Hallo, ugly,” she said. “What brings you here?”

“I understood, that you wished to talk to me.”

“I didn’t want you to come in, interrupting my work. A few words on the telephone would’ve been enough. But I suppose some instinct told you that this was my busy day.”

“If you were wondering if I could come to lunch, have no anxiety. By the way, what will Anatole be giving us?”

“He won’t be giving you anything, my young tapeworm. I am entertaining Pomona Grindle[20], the novelist, to the midday meal.”

“I should be charmed to meet her.”

“Well, you’re not going to. It is to be a strictly tête-à-tête[21] affair. All I wanted was to tell you to go to an antique shop in the Brompton Road[22]—it’s just past the Oratory—you can’t miss it—and sneer at a cow-creamer.”

I was surprised. The impression I received was that my dear aunt was a little crazy.

“Do what to a what?”

“They’ve got an eighteenth-century cow-creamer there that your uncle Tom’s going to buy this afternoon.”

“Oh, it’s silver, isn’t it?”

“Yes. A sort of cream jug. Go there and ask them to show it to you, and when they do, show your scorn.”

“What for?”

“To sow doubts and misgivings in their mind and make them lower the price a bit, chump. The cheaper Tom gets the thing, the better he will be pleased. And I want him to be in cheery mood, because if I succeed in signing the Grindle up for my serial, I shall be compelled to get some money from him. These women novelists want millions for their novels. So run away and shake your head at the thing.”

I am always anxious to help my aunt, but I was compelled to refuse. Morning mixtures of Jeeves are practically magical in their effect, but…

“I can’t shake my head. Not today.”

She gazed at me.

“Oh, so that’s how it is? Well, if your loathsome excesses have left you incapable of headshaking, you can at least curl your lip[23].”

“Oh, rather.”

“Then carry on. And try clicking the tongue. Oh, yes, and tell them you think it’s Modern Dutch.”

“Why?”

“I don’t know. Apparently it’s something a cow-creamer ought not to be.” She paused, and allowed her eye to roam thoughtfully over my face. “So you were completely drunk last night, my chicken? It’s an extraordinary thing—every time I see you, you appear to be recovering from some debauch. Don’t you ever stop drinking? How about when you are asleep?”

“You wrong me[24], aunt. I am exceedingly moderate. A couple of cocktails, a glass of wine at dinner and possibly a liqueur with the coffee—that is Bertram Wooster. But last night I gave a small bachelor binge for Gussie Fink-Nottle.”

“You did, did you?” She laughed—a bit louder than I could endure. “Spink-Bottle, eh? Bless his heart! How was the old newt-fancier?”

“Pretty roguish.”

“Did he make a speech at this orgy of yours?”

“Yes. I was astounded. I was all prepared for a refusal. But no. We drank his health, and he rose to his feet as cool as some cucumbers, as Anatole would say, and held us spellbound.”

“Tight as a skunk, I suppose?”

“On the contrary. Absolutely sober.”

“Well, nice to hear.”

This Gussie was a fish-faced pal of mine, who had buried himself in the country and devoted himself entirely to the study of newts, keeping the little chaps in a glass tank and observing their habits with a sedulous eye. A confirmed recluse you would have called him, if you had happened to know the word, and you would have been right. But Love will find a way. Meeting Madeline Bassett one day, he had emerged from his retirement and started to woo, and after numerous vicissitudes had been successful. Now he was going to marry that ghastly girl.

I call her a ghastly girl because she was a ghastly girl. The Woosters are chivalrous, but they can tell the truth. Droopy, soupy, sentimental, with melting eyes and a cooing voice and the most extraordinary views on such things as stars and rabbits. I remember her telling me once that rabbits were gnomes in attendance on the Fairy Queen and that the stars were God’s daisy chain. Perfect nonsense, of course. They’re nothing of the sort.

Aunt Dahlia emitted a low, rumbling chuckle.

“Good old Spink-Bottle[25]! Where is he now?”

“Staying at the Bassett’s place—Totleigh Towers, Glos[26]. He went back there this morning. They’re having the wedding at the local church.”

“Are you going to it?”

“Definitely no.”

“No, I suppose it would be too painful for you. You were in love with the girl.”

I stared.

“In love? With a female who thinks that every time a fairy sneezes a baby is born?”

“Well, you were certainly engaged to her once.”

“For about five minutes, yes, and there was no fault of my own. My dear old relative,” I said, “you are perfectly well aware of the inside facts of that frightful affair.”

I winced. It was an incident in my career which I don’t like to remember. Briefly, what had occurred was this. Gussie had asked me to talk to Madeline Bassett for him. And when I did so, the fat-headed[27] girl thought I was pleading mine. With the result that she had refused Gussie and attached herself to me, and I had no option but to take the rap[28]. Mercifully, things went well and there was a reconciliation between them, but the thought of my peril was one at which I still shuddered.

“Well, if it is of any interest to you,” said Aunt Dahlia, “I am not proposing to attend that wedding myself. I disapprove of Sir Watkyn Bassett, and don’t think he ought to be encouraged.”

“You know the old crumb[29], then?” I said, rather surprised. It’s a small world.[30]

“Yes, I know him. He’s a friend of Tom’s. They both collect old silver and snarl at one another like wolves about it all the time. We had him staying at Brinkley[31] last month. And would you care to hear how he repaid me for all the loving care I lavished on him while he was my guest? Behind my back he tried to steal Anatole!”

“No!”

“That’s what he did. Fortunately, Anatole proved staunch—after I had doubled his wages.”

“Double them again,” I said earnestly. “Keep on doubling them. Pour out money like water rather than lose that superb master of the roasts and hashes.”

I was visibly affected.

“Yes,” said Aunt Dahlia, “Sir Watkyn Bassett is a swindler. You had better warn Spink-Bottle to watch out on the wedding day. The slightest relaxation of vigilance, and the old man will probably steal his wedding ring. And now push off. Oh, and give this to Jeeves, when you see him. It’s the “Husbands’ Corner” article. It’s about men’s trousers, and I’d like him to read it. For all I know, it may be Red propaganda. And I can rely on you not to bungle that job? Tell me in your own words what it is you’re supposed to do.”

“Go to antique shop—”

“—in the Brompton Road—”

“—in, as you say, the Brompton Road. Ask to see cow-creamer—”

“—and sneer. Right. Go away. The door is behind you.”

It was with a light heart that I went out into the street and caught a cab. I was conscious only of pleasure at the thought that I had it in my power to perform this little act of kindness. Scratch Bertram Wooster[32], I often say, and you find a Boy Scout[33].

The antique shop in the Brompton Road proved to be an antique shop in the Brompton Road and, like all antique shops, dingy outside and dark and smelly within. I don’t know why it is, but the proprietors of these establishments always seem to be cooking some food in the back room.

“I say,” I began, entering; then paused as I perceived that the man was attending to two other customers.

“Oh, sorry,” I was about to add, when the words froze on my lips.

In spite of the poor light I was able to note that the smaller and elder of these two customers was no stranger to me. It was old Pop Bassett in person. Himself. Not a picture. But I stood firm. After all, I had paid my debt to Society and had nothing to fear from this swindler. So I remained where I was.

He turned and shot a quick look at me, and then he had been peering at me sideways. It was only a question of time, I felt, before he would realize that the figure leaning on its umbrella was an old acquaintance. And he came across to where I stood.

“Hallo, hallo,” he said. “I know you, young man. I never forget a face. You came up before me once.” I bowed slightly. “But not twice. Good! Learned your lesson, eh? Going straight now? Good. Now, let me see, what was it? Don’t tell me. Of course, yes. Bag-snatching[34].”

“No, no. It was—”

“Bag-snatching,” he repeated firmly. “I remember it distinctly. Still, it’s all past, eh? We live a new life, don’t we? Splendid. Roderick[35], come over here. This is most interesting.”

His friends, who had been examining a salver, put it down and joined us. He was about seven feet in height, and about six feet across, he caught the eye and arrested it. It was as if Nature had intended to make a gorilla, and had changed its mind at the last moment.

His gaze was keen and piercing. I don’t know if you have even seen those pictures in the papers of Dictators with blazing eyes, inflaming the populace with fiery words, but that was what he reminded me of.

“Roderick,” said old Bassett, “I want you to meet this fellow. Here is a case which illustrates exactly what I have so often said—that prison life does not degrade, that it does not warp the character and prevent a man rising on stepping-stones of his dead self to higher things.”

I recognized the gag—one of Jeeves’s—and wondered where he could have heard it.

“Look at this chap. I gave him three months not long ago for snatching bags at railway stations, and it is quite evident that his term in jail has had the most excellent effect on him. He has reformed.”

“Oh, yes?” said the Dictator. I didn’t like the way he spoke. He was looking at me with a nasty sort of supercilious expression.

“What makes you think he has reformed?”

“Of course he has reformed. Look at him. Well groomed, well dressed, a decent member of Society. What his present walk in life is, I do not know, but it is perfectly obvious that he is no longer stealing bags. What are you doing now, young man?”

“Stealing umbrellas, apparently,” said the Dictator. “I notice he’s got yours.”

I was going to deny the accusation hotly—I had, indeed, already opened my lips to do so—when I remembered that I had come out without my umbrella, and yet here I was, beyond any question of doubt, had one! What had caused me to take up the one that had been leaning against a seventeenth-century chair, I cannot say, unless it was the primeval instinct which makes a man without an umbrella reach out for the nearest one in sight, like a flower groping toward the sun.

“I say, I’m most frightfully sorry.”

Old Bassett said he was, too, sorry and disappointed. He said it was this sort of thing that made a man sick at heart. The Dictator asked if he should call a policeman, and old Bassett’s eyes gleamed for a moment. A magistrate loves the idea of calling policemen. It’s like a tiger tasting blood. But he shook his head.

“No, Roderick. I couldn’t. Not today—the happiest day of my life.”

The Dictator pursed his lips, as if feeling that the better the day, the better the deed.

“But listen,” I said, “it was a mistake.”

“Ha!” said the Dictator. “I thought that umbrella was mine.”

“That,” said old Bassett, “is the fundamental trouble with you, my man. You are totally unable to distinguish between mine and yours. Well, I am not going to have you arrested this time, but I advise you to be very careful. Come, Roderick.”

They went out, the Dictator pausing at the door to give me another look and say “Ha!” again. The proprietor of the shop emerged from the inner room, accompanied by a rich smell of stew, and enquired what he could do for me. I said that I knew that he had an eighteenth-century cow-creamer for sale.

He shook his head.

“You’re too late. It’s promised to a customer.”

“Name of Travers?”

“Ah.”

“Then that’s all right. That Travers is my uncle. He sent me here to have a look at the thing. So dig it out, will you? I expect it’s rotten.”

“It’s a beautiful cow-creamer.”

“Ha!” I said, “That’s what you think. We shall see.”

It was a silver cow. But when I say “cow”, don’t think about some decent, self-respecting animal such as you may observe loading grass into itself in the nearest meadow. This was a sinister, leering, underworld sort of animal. It was about four inches high and six long. Its back opened on a hinge[36]. Its tail was arched, so that the tip touched the spine—thus, I suppose, affording a handle for the creamlover to grasp. The sight of it seemed to take me into a different and dreadful world.

It was, consequently, an easy task for me to carry out the programme indicated by Aunt Dahlia. I curled the lip and clicked the tongue, all in one movement. I also drew in the breath sharply.

“Oh, tut, tut, tut!” I said, “Oh, dear, dear, dear! Oh, no, no, no, no, no! I don’t think much of this,” I said, curling and clicking freely. “All wrong.”

“All wrong?”

“All wrong. Modern Dutch.”

“Modern Dutch? What do you mean, Modern Dutch? It’s eighteenth-century English. Look at the hallmark.”

“I can’t see any hallmark.”

“Are you blind? Here, take it outside in the street. It’s lighter there.”

“Right,” I said, and started for the door, like a connoisseur a bit bored at having his time wasted. I had only taken a couple of steps when I tripped over[37] the cat, and shot out of the door like someone wanted by the police. The cow-creamer flew from my hands, and it was a lucky thing that I happened to barge into a fellow citizen outside. Well, not absolutely lucky, as a matter of fact, for it turned out to be Sir Watkyn Bassett. He stood there goggling at me with horror and indignation behind the pince-nez. First, bag-snatching; then umbrella-pinching; and now this. It was the last straw[38].

“Call a policeman, Roderick!” he cried.

The Dictator bawled: “Police!”

“Police!” yipped old Bassett, up in the tenor clef.

“Police!” roared the Dictator, taking the bass. And a moment later something large loomed up in the fog and said: “What’s all this?”

Well, I didn’t want to stick around and explain. I picked up the feet and was gone like the wind. A voice shouted “Stop!” but of course I didn’t. I legged it down byways and along side streets, and eventually fetched up somewhere in the neighbourhood of Sloane Square[39]. There I got aboard a cab and started back to civilization.

My original intention was to drive to the Drones and get a bite of lunch there, but I hadn’t gone far when I realized that I wasn’t equal to it. Changing my strategy, I told the man to take me to the nearest Turkish bath.

I returned to the flat late. It was, indeed, practically with a merry tra-la-la on my lips that I made for the sitting room. And the next I saw a pile of telegrams on the table.

Two

I had had the idea at first glance that there were about twenty of the telegrams, but a closer scrutiny revealed only three. They all bore the same signature. They ran as follows:

The first:

Wooster, Berkeley Mansions, Berkeley Square[40], London.

Come immediately. Serious rift Madeline and self[41]. Reply.

GussieThe second:

Surprised receive no answer my telegram saying Come immediately serious rift Madeline and self. Reply.

GussieAnd the third:

I say, Bertie, why don’t you answer my telegrams? Sent you two today saying Come immediately serious rift Madeline and self. Unless you come earliest possible moment prepared lend every effort effect reconciliation[42], wedding will be broken off. Reply.

GussieSomething had whispered to me on seeing those envelopes that here we had a big trouble, and here we had.

The sound of the familiar footsteps had brought Jeeves. A glance was enough to tell him that all was not well with the employer.

“Are you ill, sir?” he enquired solicitously.

I sank into a chair.

“Not ill, Jeeves, but I am going to die. Read these.”

He read the telegrams.

“Most disturbing, sir.” His voice was grave. I could see that he hadn’t missed the gist. The sinister idea of those telegrams was as clear to him as it was to me. There was no need to explain to him why I now lighted a cigarette with a visible effort.

“What do you suppose has happened, Jeeves?”

“It is difficult to hazard a conjecture, sir.”

“The wedding may be scratched, he says. Why? That is what I ask myself. ”

“Yes, sir.”

“And I have no doubt that that is what you ask yourself?”

“Yes, sir.”

“A difficult case, Jeeves.”

“Extremely difficult, sir.”

“What shall I do, Jeeves?”

“I think it would be best to proceed to Totleigh Towers, sir.”

“But how can I? Old Bassett would drive me out the moment I arrived.”

“Possibly if you were to telegraph to Mr. Fink-Nottle, sir, explaining your difficulty, he might have some solution to suggest.”

This seemed reasonable. I hastened out to the post office, and wired as follows:

Fink-Nottle, Totleigh Towers,

Totleigh-in-the-Wold[43].

Yes, that’s all very well. You say come here immediately, but how can I? You don’t understand relations between Pop Bassett and myself. He would not say “welcome” to Bertram. What is to be done? What has happened? Why serious rift? What serious rift? How do you mean wedding broken off? What have you been doing to the girl? Reply.

BertieThe answer to this came during dinner:

Wooster, Berkeley Mansions, Berkeley Square, London.

See difficulty, but think can work it[44]. In spite strained relations, Madeline still speaking. Am telling her have received urgent letter from you pleading be allowed come here. Expect invitation shortly.

GussieAnd in the morning, I received three telegrams. The first ran:

Have worked it. Invitation dispatched. When you come, will you bring book entitled My Friends The Newts by Loretta Peabody[45] published Popgood and Grooly[46].