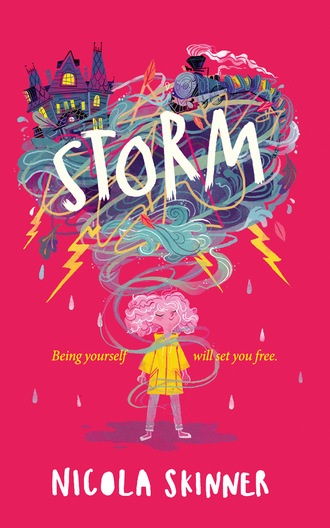

Storm

‘Very funny,’ I muttered. ‘Point taken.’

Again, this was nothing new. What I was experiencing here was that old chestnut, Let’s Pretend Our Ears Don’t Work to Teach a Child Some Manners. It was boring, it wasn’t funny, but it was clearly rather popular among the elderly.

‘No,’ said the woman, ‘but check the kitchen.’

Two of them ran off while I stared at the man nosing around our mantelpiece. There were deep shadows under his bloodshot eyes, as if he’d been on the go all night without any sleep.

Now I thought about it, the others looked pretty bad too. The way they moved had a heavy feel. They needed a couple of early nights if you asked me.

Tall Man lifted something off the mantelpiece. ‘Come and have a look,’ he shouted.

The other two ran back, all signs of exhaustion gone, and gazed down at the photo frame in his hands. I smiled when I realised what it was. Our one decent family photo.

It shows the four of us at a wedding. We’re sitting in a row along a hay bale; me and Birdie in the middle, Mum and Dad on either side. We’re flushed, catching our breath between dancing. Mum’s looking straight at the camera and laughing. She’s wearing that emerald-green dress she bought at the flea market in Swanage, red nail polish on her dirty bare feet, eyes all bright and shining.

The exceptional wonkiness of Dad’s smile, always a handy barometer in letting us know how happy he is, is dialled all the way up to ten. He’s gazing over my head and Birdie’s at Mum, and looks quite handsome, his teeth white in a tanned face, his unruly hair sort of combed for once. Birdie and I have our arms around each other. There are cornflowers braided into our hair. They look like blue stars. Birdie’s eyes are closed and she’s got the goofiest grin on as she nestles into me.

The three strangers stared at that photo a bit too long. We’re just regular human beings, guys. Seriously. You should see all our other family albums – I look dreadful in those. This was a total fluke.

And then I realised none of them was smiling. Just like that, the whole house changed. Like a drop of paint falling into water, sadness stained the room.

The woman pressed her lips tightly before releasing them again. ‘We might be looking for a family then. One man, one woman and two young girls.’

‘Er, you don’t need to find two,’ I said. ‘Just one? I’m right here. It’s my little sister

that’s miss—’

And then

my voice

tailed off.

Because I’d finally realised.

Although you guessed a few chapters back, didn’t you?

THE TRUTH DANCED in front of my eyes like it was written by a sparkler on Bonfire Night, teasingly incomplete, almost too bright to look at, fading to nothing at the end.

But could it really be true? I mean, what were the chances?

The three Coastal Rescue people ran upstairs, calling out in quick, clipped voices.

I staggered after them in a daze, as my brain began to sift through things. To test my theory, I sneaked up behind them on the upstairs landing and screamed as loud as I could.

Nothing.

Zip. Zilch. Not so much as a shudder.

The shorter man went into Birdie’s bedroom.

‘This might hurt,’ I said, and tried to kick him on his backside.

He needn’t have worried. My foot stopped just short of his swishy trousers, as if some invisible barrier protected him. He didn’t even turn around.

Gasping, I ran to the upstairs bathroom and stared at the mirror above the sink. Staring back was something stormy, strong and tempestuous – but it wasn’t me. It was one of Dad’s seascapes that hung on the wall opposite.

I waved my battered hand in front of the mirror. Nothing.

One final test.

Taking a deep breath, I hurled myself down the stairs, making sure to bang my head against the banisters on the way. Didn’t feel a thing.

I sat at the bottom of the staircase and dealt with the facts. I hadn’t woken up in wee. I had woken up in seawater.

Now I remembered what that dog had barked at so desperately. What we’d tried to run from. Suddenly, in one dreadful moment, it all came flooding back to me. As it were.

At the beginning, when we saw the wave from our window table, the fear had come in quite slyly, like it was stapled on to the end of a joke. The wave was still quite far away, just by the end of the jetty, and that was surely as close as it would come.

Plus people in Cliffstones moved slowly; nothing was done in a rush. That was the Dorset way.

So at first, we didn’t even think about escaping.

We’d just looked for a while. Gazed, while it gathered itself together, quietly, stealthily. We’d watched it. What we hadn’t realised, of course, was that it was also watching us.

Glossy as a blackberry, the sea had pleated and rippled against itself, and then it had risen, a sea monster made of the actual sea, and as it built itself up into this new, nightmarish height, it seemed to say, ‘Bet you didn’t think I could do this!’ And then it no longer looked anything like the sea I’d known all my life – the paddling, running in and squealing sea, the bright blue crabbing sea, the postcard sea of our summers.

This was a different, alien sea. This was the sea beneath. The one that made you shudder and snatch your hand out when you glimpsed it from a boat.

It was only when the wave went over the jetty, instead of around it, and tipped the people right into itself in a horrible gathering, like a malevolent mother folding children into her skirt, that the stampede inside the restaurant began, even though it had been too late by then, of course.

Mum and Dad reached for us and we ran to the door but there was too much of a crush. Dad picked up a chair and threw it at the window and we’d scrambled out of that, cutting ourselves on the glass in our rush to escape.

I looked at the nicks on my hands. Ah.

But even when we were scrabbling out of the Crab Pot, even then, some disbelief lingered. The sea – our sea, our friend – would surely realise its mistake? Would drop back down to a less threatening height? And somehow it would stop oozing towards us, would slink back, shrink back, to a safe spot beyond the harbour wall, back where it belonged, saying in a watery and very sorry way, ‘Whoops! My bad! Don’t know what I was thinking of! Here’s the people I swallowed earlier – do have them back, and let’s pretend this never happened, shall we?’ and we’d all gasp with relief and go about our day.

That was going to happen, any second.

Any second.

Once the four of us had struggled out of the broken window, we ran.

Dad, grey with fear, attempted to gather up Birdie in his arms as we stumbled along the pavement, trying to dodge the scrum around us, but it wasn’t a smooth movement and she bobbed awkwardly in his arms, her face one terrified question mark. Over Dad’s shoulder, her eyes met mine and I tried to say sorry, but my mouth was all twisted, and the wave was so close and so loud she wouldn’t have heard me anyway.

Mum gripped my hand in hers as we ran, making strange sobbing noises.

The wave was now just outside the harbour wall, just a few paces away.

It will turn back, I thought.

But it didn’t turn back. It charged.

Leapt over the wall with greedy, outstretched, frothing, white fingers. Shut the little dog up for ever. Ripped hands out of hands, people from people. And that had been that. The bruise I’d always been told to admire had turned into a bruiser and finished us right off.

I couldn’t remember coming back from the Crab Pot because I hadn’t come back.

Not alive anyway.

I was dead. I had drowned.

I held my fingernails up to my face. I hadn’t bitten them off. They’d been ripped off. I took in my ragged clothes, shredded trainers, those shells sticking out of my legs. Now they made sense. Born by the sea, died by the sea. Exit: me.

And if Dad had been with me right then and there, he’d probably have made it all about Art, by saying something meaningful in that philosophical way he had. Something like: ‘Well, Franks, really that’s got a bittersweet symmetry when you think about it’ or ‘Maybe we do always return to the source of our own beginnings.’ But he wasn’t with me and anyway he’d have been wrong.

I wasn’t a work of art. I wasn’t a thought-provoking allegory.

I was dead.

Well, technically, I was dead-ish.

I WAS DOING pretty well for myself, as far as death went. This was death with added features. I could still walk. Talk. Waggle my fingers in front of my face. The only thing I couldn’t do, apparently, was communicate with the living. Or feel physical pain where pain should be. It was a strange sensation, not having to breathe. My lungs didn’t work. My chest didn’t rise. I was just rawness, stunned with bright shock.

I closed my eyes and listened, numb, as my brain whispered questions. Questions like: Why had only I come back? Was I a ghost? A spirit? A ghoul? If I was dead, was I meant to call my body a corpse now? I stared down at myself and shuddered. And then thought: Does it matter what I call it? I had died. We had died. The shock of it shrieked through me like a forest fire. My brain whispered: What happens now?

But, most importantly of all, where were the rest of my family? And how was I meant to fill in the time until they came back?

Because they were coming back, right?

Right?

After a while, the rescue crew appeared at the top of the staircase. I automatically moved to the side of the step I was sitting on, but then a dreadful thing happened. The woman walked straight through me.

It was a sickening sensation. It was like being squished and shoved by a herd of water buffaloes. As her body moved through mine, everything I thought should remain in one place, like my lungs and kidneys and all those other delicate organs that shouldn’t, as a rule, be messed about with, shifted to the side to accommodate her. I felt like a tube of toothpaste being squeezed.

And worse than all of that was the flavour it left in my mouth. Urgh, the taste.

Have you ever tasted human flesh?

Actually, don’t answer that. Let’s just assume the answer is no. Long story short, it’s nothing like chicken. It’s disgusting. I tasted muscle and fat and blood and also some hastily digested bacon and eggs that were roughly twelve hours old. A mouthful of body.

I tasted other things too. Emotions. Traces of thoughts. Sorrow and grief and fatigue. It was like something wet and cold crawling across my tongue.

She emerged out of me with a small but audible squelch. And then, because I hadn’t moved from the step, it happened AGAIN.

And then ONCE MORE JUST FOR FUN.

Once they’d all had a go, I wanted to be sick. The sour aftertaste of three humans mingled on my tongue.

The three of them gathered in the hallway. They looked shattered.

Not Mum looked into the faces of the others. ‘I’m calling it. Agreed?’

After a pause, the other Nots nodded.

She reached for her walkie-talkie. ‘This is Rescue, over,’ she said.

The device in her hands gave out a blare of static.

Someone said, ‘What’s the report, over?’

‘No survivors found. House checked thoroughly. We presume the family perished down in the harbour. There are no coats or boots in the porch and the house is empty. Over.’

Over.

There was a pause, then the static voice said, ‘We’ll circle back. Get ready to leave in approximately twelve minutes, over.’

They moved towards our broken front door. Tall Man rubbed his eyes and hung back. Not Mum touched his shoulder.

‘Ed,’ she said gently, ‘we’ve done all we can. There’s no one here.’

He sighed. ‘I just … keep feeling like we’ve missed something, you know? I have the strongest feeling that someone’s still here.’

Is he talking about me? Can he … somehow sense me?

‘Let me check downstairs again.’

In the sitting room, I gave it my all. I shouted until my throat ached. But although he heard something – that much was clear from the way he repeatedly stopped and cocked his head – I couldn’t get through. He was plainly a sensitive type – he could feel that I was around, but that was all.

Something made him stop. He picked up the newspaper on the floor. The one Dad had been trying to read until I …

Until I …

What, you want me to tell you twice? It was hard enough the first time.

He rifled through the paper and threw it on the floor again, looking crestfallen.

I hurried over. It had fallen open at a double spread. The headline read:

FREAK EARTHQUAKE ON COAST OF FRANCE KILLS HUNDREDS AND MAY NOT BE DONE YET, EXPERTS WARN.

I peered at it. Next to the headline was a map showing exactly where in France the earthquake had struck: a little town called Omonville-la-Petite. Cliffstones was almost directly opposite it. Only a matter of miles, really, across the English Channel. My eyes flicked back to the headline.

MAY NOT BE DONE

Back in the hallway, Tall Man rubbed his eyes. ‘It’s tragic, really. They had the facts at their fingertips. If only they’d realised what that earthquake would do—’

‘Stop,’ said the other man gently. ‘No use thinking like that. Lots of things should have been done differently. Experts should have issued a warning earlier. It didn’t help that there was a power cut just before it struck, and there’s so little connection here, I doubt anyone would have seen the alerts on their mobiles in time anyway. It’s just horrible bad luck.’

The sound of the helicopter, growling in the sky, grew louder.

Tall Man sighed. ‘It’s just so desperately sad that this family drowned when they lived in the safest place in the entire village. If they’d stayed, they’d have lived. And then the village wouldn’t have been wiped out completely.’

Silently, the woman touched his arm, tilted her head in the direction of the door. The three stepped out of the broken doorway into the roar of the helicopter outside.

I sank on to the hall floor, my thoughts scattering like a flock of seagulls. The full realisation of what he’d said – what I’d done – sluiced over me, just as cold, just as deathly, as the wave.

No survivors. Wiped out completely, he said.

But if we’d stayed at home, we’d have lived.

But we didn’t get a chance to stay at home, did we?

No.

And whose fault was that?

Yep.

Little old me.

THIS IS ALL my fault. None of my family had wanted to go out for lunch! They’d wanted to stay at home by the fire! They only came out to please me, because they were kind and loving. And I’d repaid that love by leading them right into the mouth of a monster that had swallowed us up as casually as a sweet.

I cupped my head in my hands. My battered fingers explored my new dead face. They discovered the open wound next to my right eyebrow, the cut on my nose, grazes down both cheeks: the result of being dragged along the seabed for a couple of hours.

Oh, do you like my makeover? Yeah, I got it from the universe. Why? Well, I fancied a spot of lunch with my best friend, to stop her becoming best friends with someone else, and basically murdered my entire family. You get the face you deserve, so here’s mine, messed up and nasty, just like my HEART.

Guilt, like a million tiny fish hooks, twisted and caught inside me.

A good cry will make you feel better – that was what Mum always said, and I tried to get one going, but proper tears wouldn’t come, because: a) I didn’t deserve to feel better and b) my tear ducts were dealing with a permanent shutdown, because c) I was dead.

The booming helicopters grew quieter, then faded completely. The only sounds in the house were my ragged, dry sobs. I pulled each name out of me with an awful cold sorrow, like counting marbles out of a bag.

Mum.

Dad.

Birdie.

Me.

Ivy, and her family, and my teachers and my classmates, and the woman at the fish-and-chip shop, and the nice man who sang sea shanties on the bench by the boathouse every Saturday afternoon.

Birdie’s best friend, little Emma, who always had slightly crusty nostrils, but we all loved her anyway and …

The man who dropped the milk off and …

Our school hamster.

The white dog who’d tried to warn us.

Everyone. Everyone I’d ever known. My village. My entire life.

When I closed my eyes I saw terrible things, frightened faces and outstretched hands caught for ever like insects in amber.

I was desperate to breathe, to swim to the surface of my grief and take a deep, juddering intake of air, escape the pain. But the sea had stolen my last breath. Instead my mouth opened and shut hopelessly, like a fish that knew its time was up.

Hours passed. I sat in a damp heap on the hallway rug, my clothes still wet, my skin still wrinkly, as the sky darkened.

The gently flickering fairy lights strung on the stairway banisters spluttered until their batteries ran out and then the gloom of the house wrapped its arms around me. And still I sat, and waited for Mum and Dad and Birdie. I was desperate to see them and say sorry. I yearned to hug them, to look into their faces and be scolded, then forgiven. And my brain clung desperately to this flicker of hope, like a raft.

They won’t be much longer. They won’t. They’ll be back. Any minute now.

Any.

Minute.

Now.

MOONSHINE HAD BEGUN to struggle through the clouds beyond the door. Still no one came. What were they doing, coming back via the scenic route?

I peeled myself off the floor, leaving a damp patch behind. There was a wet sheen of moisture on my skin and the salt tang was still in my mouth. I had that horrible wet chill you get if you’ve worn a damp wetsuit too long. Was that normal? Was I always going to look and feel as I did at my moment of death? Wet and battered and coated with sea salt? Studded with shells like a trinket box from a seaside gift shop?

Oh, what was taking them so long? Did they need a sign I was here, waiting for them?

I ran to the kitchen. A torch was what I wanted. I’d flash out some Morse code from our back garden. If they were in the waves, they’d read my message and come back.

There was just the tiniest problem. I didn’t know any Morse code.

Make that two problems.

I couldn’t open any of the kitchen drawers to find a torch in the first place. It didn’t matter how hard I tried, my fingers slid off their surfaces. I remembered how my attempts to connect with that man’s backside had failed – my foot had just darted off at the last minute, like the wrong end of a magnet resisting another.

Yet I was able to touch my own body. I could pull shells out of my rubbery dead skin and run a hand through my matted salty hair, lucky me. But I couldn’t physically touch anyone that was alive.

And, it appeared, the same rule applied to physical stuff – bits, glass and wood and metal and other people. Anything outside me, essentially.

I glared at the drawer. Our torch was inside it. I tried to hit the handle as hard as I could, scrabbled at it, banged it with frustration, even resorted to growling at it, but no dice. Getting any kind of grip on the handle remained impossible.

So: I could sit on a step but I couldn’t open a drawer. I could walk up and down the staircase and move through rooms but I couldn’t open a door. I could hear and see people that were alive, but I couldn’t make them see and hear me. Things could happen to me, but I couldn’t make things happen.

So far, being dead wasn’t what I’d call an empowering experience.

Maybe there was one thing. If I was dead, could I …

… fly?

I did try hard. I gave it a good go. By which I mean, I hopped about a bit, flapped my battered arms and hands around, leant forward and strained, frowning, into space. Nothing.

Flightless as an emu.

There was literally nothing cool about being dead at all.

I slapped a hand to my forehead.

None of this mattered.

Why was I getting distracted? I needed to contact Mum, Dad and Birdie before they spent another night out – I glanced through the study window and shivered involuntarily – there. Whether or not I could move through a door or fly was totally insignificant compared to that.

Luckily the front door was still open – swinging off its hinges from being kicked in earlier by the rescue crew. I ran through it and then circled round the house, towards the back garden that faced the sea.

‘MUM! DAD! BIRDIE!’

The night swallowed my words up silently.

I cast them out again.

‘I’M HERE! FRANKIE! I’M AT HOME! PLEASE – COME BACK!’

In the dark, the sea smiled its treacherous wet smile, replete from its feast.

‘I’M SO SORRY WE’RE ALL DEAD! REALLY, REALLY SORRY!’

Out of the silver clouds came a cry. Was it Birdie, calling my name? I held myself still, like a quivering arrow, desperate to hear her again.

But it was just a stupid gull, saying, EEEE, EEEE.

What else could I do to find them? Shouting into the darkness wasn’t enough.

I had to go to the place where it happened.

To the harbour. Right away. Not a moment to lose.

FIRST OFF, BETTER get my coat. I turned back to the house, then stopped. I’d never need to think about putting on my parka again, which was probably just as well. I must have lost it in that giant wave. Some fish was probably wearing it; a gurnard, most likely. They always looked like they were after something.

I ran into Alan the bull’s field. He looked alarmed, his ears pricked up, and then he reared up on his hind legs and went charging off into the distance. It was sort of gratifying and, on this dreadful day, I would take any comfort I could get. Not such a big scary boy now, are you?