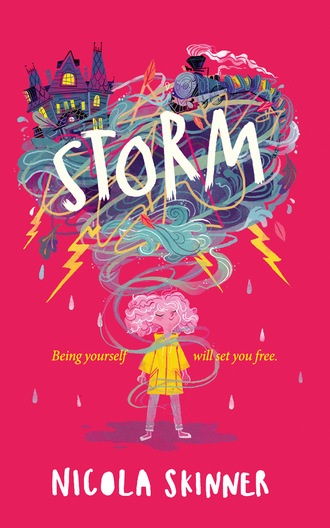

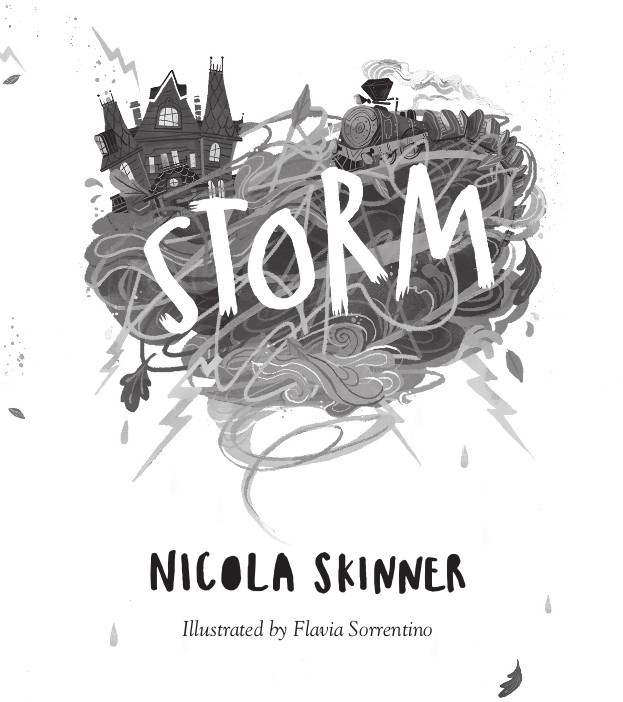

Storm

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Children’s Books in 2020

Published in this ebook edition in 2020

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd,

HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

The HarperCollins Children’s Books website address is

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Text copyright © Nicola Skinner 2020

Illustrations copyright © Flavia Sorrentino 2020

Cover illustrations copyright © Flavia Sorrentino 2020

Cover design copyright © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2020

Nicola Skinner asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of the work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook onscreen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008295325

Ebook Edition © April 2020 ISBN: 9780008295349

Version: 2020-03-17

All of this book is dedicated to Ben and Polly. Except for a few chapters towards the end, which are for Meg and Saul.

Poltergeist: a type of ghost or spirit responsible for loud, chaotic and destructive disturbances. A noisy ghost.

From the German poltern (to make sound) and geist (ghost).

Some people think we don’t exist.

They’re wrong.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Part 1

1. A Bit Eggy

2. My Birth Story

3. Buzzes

4. Freak Earthquake

5. A Dying Art

6. I Could Have Handled This Better

7. A Bad Batch of Hot Chocolate

8. They May Be Injured

9. Family Photo

10. The Truth

11. Human Flesh is Yuck

12. Not Very Proud of Myself

13. Life’s Tricky When You’re Dead

14. Thieving Gurnards, Ships in the Night

15. Get on Board, Duckie

16. A Manufacturing Snag

17. Legs and Other Problems

18. Later that Evening

Part 2

19. Sometime Later

20. Look Out for Rats

21. Shoes in the Hallway

22. Mysterious Signs, Disturbed Foxes

23. Bats in the Dark

24. Something Fishy This Way Comes

25. Make Yourself at Home

26. You’re Here!

27. Your Information Pack

28. The Calm Before the Storm

29. When They Took the Ropes Away

30. The Boy

31. There’s Only So Much a Dead Girl Can Take

32. The Face in the Doorway

33. ‘Poltergeist’

34. The Chat

35. Did I Get it all Wrong?

36. An Understanding, of Sorts

37. Friendship and Riddles

38. A Lullaby

39. Shining Eyes, Smashing Glass

Part 3

40. Where am I?

41. It’s Where We Live

42. Scanlon’s Secret

43. The Thing in the Woods

44. There are Others

45. People in Cans

46. Crawler Lane

47. The Icing on the Cake

48. Someone at the Door

49. Crawler’s Special Cocktail

50. Will does Some Counting

51. Temptation

52. Switch it on, Switch it off

53. Go and Do Your Thing

54. Wild Success and Dancing Monkeys

55. Birthday Surprise

56. What are We Doing?

57. An Unwanted Present

58. Party Tricks and Birthday Cake

59. Package D

60. Haven’t you Grown, Scanlon?

61. Not Just me, not Just you

62. Like Father, Like Son

63. Defective

64. Scanlon’s Plan

65. Jill the Death Guardian

66. Who am I? Who are you?

67. All This Will Fade Away

68. We Need to Practise our Moves

69. Final Act

70. Curtain Call

71. Let the Light in

72. I’m Ready

Thanks to

Keep Reading …

Books by Nicola Skinner

About the Publisher

WHEN YOU’RE BORN, you’re a baby. That’s something we can all agree on. But you’re not just a baby. No.

You’re a story.

A beautiful, bouncing, gurgling story.

A tale to be treasured.

And not just one story either. You’re all of the stories, all of the time. You’re an adventure, a love story, a thriller, occasionally a horror – yes, I am looking at you, you naughty little scamp – all rolled into one. And every day is story time now you’ve arrived.

Basically, babies are page-turners, and will only get more fascinating with each passing day. Or that’s what their parents think anyway.

Even if no one else does.

Parents love talking about their children, don’t they? Stick around any school gate long enough and all you’ll hear is: ‘my treasure this’ and ‘my darling that’. And what do they love to talk about the most?

Our beginning.

Also known as the Birth.

This part is special.

It is sacred.

It is long.

Have a look around. Go on.

Are there parents nearby? Is their conversation turning towards childbirth? Do any of them have a funny misty-eyed look on their face? Is anyone – this is the clincher – clearing their throat?

If the answer to any of that is yes, then I ask you this. Have you got an escape route? If you have, run to it. Now.

If not, tough luck. Did you have something planned for the day? Not any more you don’t. Because when a parent breaks into a birth story, it takes a while and there’s nowhere to hide.

You will hear:

a. When the contractions started.

b. Which hospital they decided to drive to.

c. What song was on the radio in the car.

d. Whether that glitchy traffic light had been fixed.

Not to mention:

a. How much the parking cost.

b. Whether that was reasonable.

c. What pain relief was available.

d. And how much the baby weighed.

(This last bit captivates them all, for some mysterious reason. Like farmers and their prize-winning turnips, parents are obsessed with how much their babies weigh. Why? Who knows? Ask them, if you don’t mind waving goodbye to another day of your life.)

Anyway, you’d better pay attention. Make sure you listen closely and nod thoughtfully in all the right places, as if you’re having a fantastic time. If you don’t listen hard enough, they’ll somehow know, with that uncanny parental sixth sense, and start all over again from the top. Then it will be YOU asking for pain relief.

For your ears.

And I’ll tell you another thing. For your entire life, how you were born will be used to explain you. Why you are how you are. Parents will say stuff like ‘Oh, it’s no wonder our Jasper is so good at ballroom dancing – after all, he was born on a Tuesday just after I’d had a ham sandwich’ or ‘Well, of course Deidre’s a dawdler – she was born just shy of the M25!’, and all the other parents will nod solemnly like this makes total sense, pour themselves another cup of tea, and say, ‘Tell me again what she weighed.’

Mine were the same. They’d bring up the way I was born at the drop of a hat. Especially when I was cross. And they’d always say the same thing: ‘Well, that’s what happens when you’re born in a storm.’

This, of course, would only make things worse. I mean, it’s very difficult to discuss the injustice of the recycling rota when your parents just keep bringing up the weather.

From eleven years ago.

It didn’t end there either. Once they started, there was no stopping them. My birth story was so well rehearsed in our house it was like a duet. My parents had their lines and they knew them well.

That’s how Dad would start. ‘Salty from the get-go, you were.’ (Frances Frida Ripley is me by the way. Hi. Except I’d rather you didn’t call me Frances, if that’s okay. Frankie’s fine.)

Then Mum would interrupt. ‘Well, love, that’s not completely true. Frankie was a very peaceful baby girl. A little wet, a bit cold, perhaps, but so calm. So still. You looked as if you didn’t have a care in the world.’

That would have been the hypothermia kicking in, Mum.

‘Yeah, you were peaceful, for all of a second,’ Dad would add. ‘Right up until the moment you took your first breath.’ Tiny smiles would fly between them, like birds swooping home. ‘That was when you started raging. And you haven’t really stopped since.’ Then, at a look from Mum, he’d mutter, ‘But we wouldn’t have you any other way, of course’ and lope off towards his painting shed.

But here’s my take on it: what did they expect? Of course I lost my temper when I was born. I mean, they were the ones who decided to have a baby on a freezing beach! On top of some pebbles! In the middle of winter! In a storm! No wonder I got a bit eggy. Any sensible baby would.

ANYWAY, IT WASN’T my fault. It was their idea to head down to the beach that day, even though Mum was heavily pregnant with me. Even after they saw the thick black storm clouds circling our small village.

They could have done something sensible instead, like driving to the nearest hospital on a test run, making a careful note of how much the parking cost and whether that was reasonable. Perhaps then I would have turned into a very different child and this would be a very different story.

But they weren’t practical people.

‘I wanted to paint the storm,’ Dad said. ‘Stand inside it. See its colours.’

Dad said stuff like this regularly. He was an artist. He was nuts about colours. For his day job, he painted pet portraits. Didn’t matter if they were scaly, hairy, sweet or scary, if you had £275 to splash out on a nine-inch by twelve-inch painting of your pet (unframed) then Dad, also known as Dougie Ripley, also known as –

– was your man.

In his spare time though, he painted the sea.

‘I’ll never get close to showing the sea the way she looks in my head,’ he’d say to us – us being me and Birdie (my six-year-old sister).

‘Why paint it then?’ we’d ask.

In reply he’d tap the side of his nose and smile his wonky smile. ‘It’s the pull of it,’ he’d say then. ‘You can’t deny the pull of it.’

Whatever that meant.

And don’t even get me started on Mum. She was practically nine months pregnant on the day of the storm. She could have sat about on the sofa complaining about her swollen ankles, like any normal pregnant woman. She could have said, ‘No, Douglas Ripley, we are not going to the beach in the middle of a hurricane, not on your nelly. Now drive me to the nearest hospital so I can have this baby, and put the radio on because apparently that’s important.’

But she didn’t.

‘I was sick of staring at our four walls, Frankie, and I thought the sea air would make me feel better. You weren’t due for another week anyway, so you can take that look off your face for starters.’

Here’s what they didn’t take:

1. A phone.

2. A car.

3. Anything practical in case one of them gave birth.

Here’s what they took:

a. A moth-eaten picnic blanket.

b. Mum’s favourite coral lipstick.

c. Dad’s easel and paints.

Anyway, unsurprisingly, Mum went into labour just after they got to the shingle beach down by the harbour. No one else was around, what with it being January. And the storm. And having normal brains.

And without 1, 2 and 3, it finally dawned on Mum and Dad that I was going to be born right on top of a. The moth-eaten picnic blanket. So they threw it on top of some lumpy pebbles and hoped for the best. Which was completely against NHS guidelines at the time, especially under the bit called ‘Good Places to Have a Baby’.

I was not swaddled in a comfy hospital blanket and cooed over by nurses. Instead I was bundled into a damp hoodie and seagulls squawked over my head. To cap it all off, I opened my mouth for some milk but got a mouthful of salt spray instead. And that was my first taste of the world:

According to Mum, it moulded me for ever. ‘You changed, right then and there,’ she’d say. ‘I watched the storm come over you, as sudden as a fever. You clenched your tiny fist and you raged up at the sky, like you were having a competition about who could be louder.’

A coral smile would flash on her lips, quick as a fish. ‘And sometimes I think a bit of that storm’s been stuck inside you ever since.’

Then she’d wander off in the direction of her study, stopping on the way to make her one billionth coffee of the day. Then, just as I’d begin to think I’d got away with it, she’d say, ‘Oh, and don’t forget to put the recycling out.’

And that was my birth story.

But here’s an inescapable fact about being born. You might live until you’re 101, experience wild success and mountain peaks and dancing monkeys, but however you live and whatever you do, the story of your life will end with a death.

Yours.

That’s the deal. Because the thing about human stories is: they all finish more or less the same way. On the final page. The end.

But because you’re dead you never normally hear that bit. Normally.

THAT LAST CHRISTMAS – our last Christmas – I grew strange to myself. My emotions felt wilder, my moods harder to control. I’d slam doors and cry for weird reasons.

‘Hormones,’ Mum would sigh to Dad when she thought I couldn’t hear.

I’d heard about those. I wasn’t completely sure what they looked like, but I had a feeling they weren’t good. Like dark things flapping about inside me. Like the massive wasps’ nest we’d found behind the wall in Birdie’s bedroom once.

Recently I’d been wondering if there was just a thin wall between me and my hormones too. That if you peeled back my skin there’d be an angry, quivering nest deep within my bones and all my words would turn to buzzes

that

no one

understood.

Other words I heard a lot: Hot-tempered. Temperamental. Moody. Volatile. Quite bolshie, for an eleven-year-old. They were written in my school reports. They were uttered in parent meetings. They were said about me so often that sometimes I didn’t know where I ended and those words began.

And I’m not saying that to excuse all of this – I’m just saying it. In the interests of a balanced debate.

It was the last day of the Christmas holidays. I was in Mum’s study. My best friend Ivy was on the phone.

‘Can you come for lunch at the Crab Pot?’ she asked.

The Crab Pot was the new restaurant down by the harbour. I’d never actually been inside, but I’d heard good things. Its white chocolate cheesecake was the talk of the village. Ivy said it was delicious.

So did Thea Thrubwell.

Thea Thrubwell had been hanging around us for an entire term. She looked like she was angling to become Ivy’s best friend instead of me. I felt like I’d been signed up for an invisible competition that no one was talking about, but which I was frankly losing.

Thea was in Ivy’s Guides group, and I wasn’t.

(I’d been thrown out because of a disagreement with my Guides leader. Well, I called it a disagreement – she called it arson. But I never meant to start a fire during the annual Scouts and Guides fundraiser disco. It was those tea lights that were faulty and, like I told the investigating officer at the time, you didn’t need a Fire Safety Badge to see that.)

Thea had a pony.

Thea had shiny brown hair that didn’t go frizzy in the rain.

Thea hadn’t burnt down any buildings.

Allegedly.

‘Oh, and Thea Thrubwell is coming too. Is that okay?’ said Ivy.

Obviously, it was not okay.

‘I guess that’s okay,’ I said.

Thea Thrubwell was bringing her family too, which was just great.

‘Our mums get on really well,’ said Ivy. ‘They do yoga together in the hall. Well, they did, until it was shut for the refurb—’

‘Mmm.’

‘Okay. See you at See Pee then.’

‘Where?’

Ivy laughed. ‘It’s just what we call it. It’s the initials for Crab Pot. CP?’

‘Oh, yeah. Great. See you at the Pot. That’s just what we call it, me and, er, them.’

I put the phone down and took a few deep breaths. Then I walked to the sitting room.

Arthur Christmas was on the telly for what felt like the hundredth time. Birdie was doing her new jigsaw puzzle. Mum was flicking through a magazine with one eye on the screen. (And the only yoga she was doing was stretching for the bottle of Prosecco by her feet and pouring it into her chipped QUEEN MUM mug.) Dad was fiddling about with paper and kindling in the fireplace.

‘Can we go to the Crab Pot for lunch?’ I said.

‘That pricey place in the harbour?’ Dad looked as enthusiastic as if I’d suggested grabbing a bite at the local crematorium. ‘I guess. One day.’

‘No, can we go today? Ivy’s going with her family and invited us along too. I said we’d go.’

‘You should have checked with us first,’ said Dad, lighting a ball of newspaper in the grate.

‘I’m checking with you now.’

Mum and Dad looked at each other.

‘It’s a nice idea, love,’ said Mum, lifting my hopes, only to dash them again by adding, ‘but we need more notice than that. Also, there’s no point eating out when we’ve got so many leftovers. All that turkey isn’t going to eat itself. Another time.’

‘But if you want a fancy lunch out,’ said Dad, missing the point entirely, ‘how about an al-fresco lunch in the garden? It’s got the best view in the village, and it’s totally free – you can’t argue with that.’

He really did think everything was brilliant if you did it in terrible weather. Even then, he was staring outside at the drizzly rain and churning ocean as if it was the most beautiful thing he’d ever seen.

Our house was called Sea View for a reason. A three-hundred-year-old, small fisherman’s cottage built at the top of the highest hill behind Cliffstones, it offered panoramic views of – you guessed it – the sea, from every single room at the back of the house. When Mum and Dad had bought it, it hadn’t had any electricity or running water. As they were fond of reminding us, our house was a labour of love. They’d spent almost every evening and weekend doing it up. Dad had been up on the roof the day of their wedding, and they spent their honeymoon putting in window frames.

And although Dad often talked about it like it was the greatest masterpiece he’d ever done, to be honest with you, I didn’t think it was completely finished. It was rickety. It was rackety. It was freezing in the winter if we ran out of gas or wood. The roof was always leaking somewhere. And it wasn’t that clean and tidy either. According to Ivy’s parents, Mum and Dad were ‘free spirits’. Now, I don’t know what free spirits do elsewhere, but in my house, they stayed up late listening to terrible folk music, took us camping in woods with no toilets, and were generally allergic to housework.

Those coffee cups dotted on every surface in Mum’s study would sit there for weeks, quietly growing little personalities of their own, until she decided to do something radical about them, like take them to the kitchen. The piles of paperwork on her desk were so layered they could qualify for their own archaeological dig.

Dad wasn’t much better: he wore the same jeans until they fell apart, had permanently grubby fingernails, and trailed a smell of paint, turps and rollie cigarettes wherever he went. And, as you’ve just seen, he had very random ideas about what we should do with our spare time, and it wasn’t eating lunch at the Crab Pot. According to him, if you wanted to do something cool, all you had to do was paint in a storm, give birth somewhere inappropriate or (and this was scraping the barrel) literally look out of a window.

‘Drink in the colours, girls!’ was the rallying cry in our house. ‘Take in those views!’

As you can imagine, this could get annoying. As far as I could tell, the sea came in three different colours: blue, green and grey. It was like being told to constantly admire a bruise.

I RENEWED MY efforts in the Crab Pot Campaign. ‘But I haven’t seen Ivy for ages!’ I said. ‘Not for the entire holidays! Please can we go? Please?’