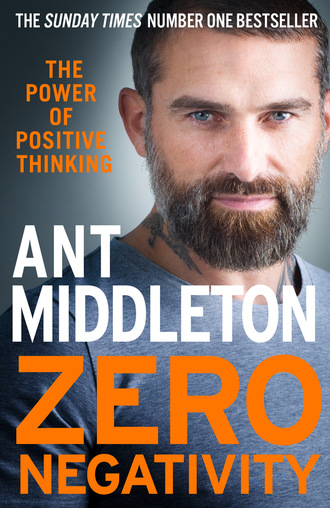

Zero Negativity

Although I didn’t necessarily realise it back then, it was thinking positively that helped me to thrive in the armed forces. It was thinking positively that meant I could go into combat feeling as if I were bulletproof. And it’s been the same ever since. My positive mentality has enabled me to overcome setbacks that might otherwise have been fatal; and it has allowed me to seize opportunities that another person might have let slip through their hands.

I was born positive. Maybe it was something I inherited from my father or absorbed from him in the short time I was with him on the planet. But my mindset is also the result of the way my life has unfolded. Don’t get me wrong – it’s been a long, tough process. The growth of my positivity has been mirrored by the ways in which I’ve grown as a man. The missteps I’ve taken have been just as significant as the moments when I’ve looked to be flying. I wasn’t the finished article when I was in the Special Forces, and I’m far from the finished article now, but I know I can look back at key moments in my life and tell myself that I’ve drawn the right lessons from them. I’m not sure I’d have been able to attain this knowledge had I not been through trials and tribulations, shit moments and low days, setbacks and outright failures.

Usually in this kind of book the author will tell you that he’s sharing his mistakes so that you can avoid making the same ones yourself. I’m not going to do that in Zero Negativity. I want to show you that if you never make mistakes in life, you never make anything. Nobody in the history of the world has ever been perfect. Nobody. You’ll never be perfect, and that’s OK, that’s human. But what you can become is the best version of yourself. Fucking up can be as valuable to your personal development as any university course. I needed to find myself in a position where I was making the same stupid mistakes over and over again – getting into fights, drinking heavily – before I reached rock bottom. And if I hadn’t sunk to those depths, I know for sure that I wouldn’t be in the position I’m in now.

There’s nothing complex about my philosophy. If you tackle a negative situation with a positive mindset, you’ll find a solution. If you tackle a positive situation with a positive mindset, then it’s win–win: you’ll be through the clouds. So why wouldn’t you give yourself that built-in advantage? Why would you want to tackle anything in life with negativity? Having a negative mindset effectively means tying one hand behind your back.

Sometimes I ask people, ‘Have you ever been excited about waking up?’ Very often, I’ll know the answer before it’s even left their lips.

‘No.’

‘What, never in your life? Not even on Christmas Day when you were a kid?’

‘Well, yeah, of course.’

‘You were in a positive mindset then, because you were going to get presents and eat turkey. They’re feelings you’ll never forget.’

‘For sure.’

‘Then why don’t you have them now? You don’t put yourself in the right situations, you don’t grab opportunities, you don’t think positively.’

Most kids are naturally positive, whereas a lot of adults seem to have dedicated large portions of their life to deleting their capacity for positivity. We’re told to worry about exams, we’re told that we’re not bringing up our children right, we’re told that we should have a particular kind of job by a particular point in our life, we’re told that we should be climbing up the property ladder. Conformity to these sorts of ideas is imposed upon us, and its effect is often very negative. You’re expected to get in line with all these things, and you get so involved in doing so that you develop a one-track vision. We get so focused on the path that others have laid out in front of us that we forget to ever look up and take in the world around us.

We need to rediscover that excitement we felt when we were a kid, when the world appeared big and exciting, and everything seemed new and full of adventure. As most people get older, their horizons narrow; they tend to think more about what they can’t do than what they can.

I’m different. I’ll try to seize a positive from any negative situation that comes along. Sometimes it’s obvious, sometimes it’s not. Sometimes you don’t think you’ve been able to extract any benefit until, having parked it up, three or four years down the line you realise its significance or how it connects to other elements in your life. If you’re a positive person, you can leave negative experiences on the shelf, safe in the knowledge that they’ll come in handy one day. They’re there, but you don’t let them distract you.

Over time I’ve trained my mind so that I approach every situation I’m in with a positive mindset. It comes naturally, without thinking. I’ve got to the point where I’m such a positive thinker that I’m permanently convinced that good things will come my way. If I told you what I see when I look ahead towards my future, you’d think I was an absolute madman. All I see are bright lights. And that was as true when I was in my prison cell, or sitting in the pissing wet of an Afghan hillside, as it is now.

When I left prison in 2013 I had £10.52 to my name. Nothing, really. But I was excited. I was at the bottom, and I knew I only had one way to go. I’ve got a rock-solid foundation now and I’m building, building, building. Charities, tech companies, clothing brands. I want everything life can give me.

I can see how some people might think I’m delusional. But I’m a realist. I believe I can get there. I can back everything up. I know I’m willing to work, sacrifice and suffer to get to the place I want to reach. I’m willing to try and fail, try and fail, try and fail until I get it right. I’ve got so much positive energy now that I sometimes feel as if you could run the National Grid off me.

What I want to do in this book is help you tap into the same.

Everything I do now – books, TV programmes, speaking tours – it’s all because I want to help people develop and make them realise what they’re capable of. I’m fascinated by people, I’m fascinated by their potential, and also by the fact that most of us only use a quarter of our power. I find that really frustrating. Negativity is the thing that, maybe more than any other factor, will put a limit on your ability to be the best version of yourself you can be.

The good news is that you’re not doomed to negativity. There’s a way out. Everybody can train themselves to think positively and tackle negative situations with a positive mindset. It just takes a concerted effort. You may not feel positive all the time – nobody does – and yet eventually you reach a point where you’re automatically tackling every situation with a positive mindset. It takes time and it requires brutal honesty, but it’s worth it. While I’d never say that you’ll be invincible, I guarantee that not much will faze you.

Once you’ve mastered a positive mindset, you’ll be excited to take on negative situations because you’ll be desperate to see what their outcome will be. You’ll see them as opportunities to discover where the limits of your potential lie and as chances to learn new skills, experience new things.

When a positive situation comes along, and you dive into it with a positive mindset, you’ll feel like you’re flying, or as if you’ve been transported to another dimension. I often experience extended phases of complete euphoria, riding the clouds with Zeus looking down on the world, endorphins racing through my veins. It can get to the point where I can’t even get to sleep because I’m so excited about getting up the following morning and re-attacking life. This mood can last for weeks, each day speeding past in the blink of an eye.

Living a life with zero negativity has many physical benefits. It will encourage you to follow a healthier, more productive lifestyle. Studies show that positive people get more physical activity, eat a better diet and are less likely to smoke or drink alcohol to excess. In addition to this, current research shows that positive thinking can confer many health benefits, including lower rates of depression and psychological distress, greater resistance to the common cold and reduced risk of death from cardiovascular disease. They even think it will help you live longer. And the more positive you are, the better your relationships with everyone around you will be.

Being negative is isolating. Negative individuals don’t tend to have many friends. By contrast, positivity attracts other people. When you’re positive, you’ll find that others just want to be around you – it’s as if you’ve become magnetic. And being around somebody who exudes positivity is the most powerful thing. It can feel tiring at times because they’ll be a mass of whirring energy, but you’ll come away with excitement and inspiration pumping through your veins.

These are all good things, but it’s the mental advantages positivity can offer that I’m most interested in, and which will be the focus of this book. In the chapters that follow I’ll show you how to embrace failure and use it to your advantage, how to learn to see change as the foundation of your future success, how to develop resilience, how to deal with bullies online and offline, what it means to be a positive father, how to make and seize opportunities for yourself, and how to live a life with no regrets. I’m not here to tell you who to be, where you should live or what job you should do. All that is up to you. What I do want to do, however, is to give you the tools you need to become the best possible version of yourself.

One last thing. My voice isn’t the only one you’ll hear in these pages. Each chapter will feature my wife Emilie’s take on whichever subject I’ve been talking about. My life has been improved a million times over by her kind, measured, no-bullshit perspective. I’m sure that yours will be too.

CHAPTER 1

I KNOW WHO I AM

Ahead of Series 4 of SAS: Who Dares Wins, one of the producers asked me in for a meeting. ‘Ant,’ she said, ‘how do you feel about us changing things up a bit?’

Not long before we met, the British Army had announced that, from that point on, women would be allowed to apply for every single role in the military, including combat roles, with the Royal Marines doing likewise. For the first time in its history, recruitment would be decided by ability alone, and gender wouldn’t have anything to do with it. The producer had suggested that we should follow suit and include female contestants.

Initially, every instinct told me to steer clear. ‘I’m not sure,’ I told her. ‘This isn’t for us to do. It’s going to be complex – maybe it would be better if we left this to the army and Marines?’

I could see my producer was still thinking about it. Then she surprised me by asking me what it was I looked for in recruits for the show.

This was an easy one to answer: ‘I’m looking for all-round, balanced individuals.’ As soon as I said it, I realised something: that last word. It doesn’t matter if it’s a male or female – it’s about an individual. What’s most important is that they’re somebody who knows themselves better than anybody else; somebody who knows their strengths, but who also acknowledges that they have weaknesses and insecurities. Within hours of the start of filming I saw how tough, driven and resilient the female contestants were. It was eye-opening to watch the way they threw themselves heart and soul into every challenge. They fought as hard as the men, maybe harder. I instantly regretted my original reluctance. Having women alongside men added a completely different dimension to the programme.

The whole show is about putting all the contestants under a microscope, exposing them to such high levels of stress that they’re forced to confront elements of their personality that they’ve tried to keep hidden. Many discover talents within themselves that they never knew existed, others are surprised to find fault lines that, under pressure, start to crack apart. There’s no contestant, no matter how far into the competition they get, who comes away without a greater understanding of every aspect of their personality. What I realised was that I still had lots to learn too.

If there was any positive to be gained from the upheaval and distress of my early years, it was that during that period I picked up the habit of self-reflection. Like the men and women trying to get through to the end of SAS: Who Dares Wins, an intense period of disorientation and discomfort helped me gain a new knowledge of myself. If I’d had a more normal upbringing, I bet I’d have continued on a happy, oblivious path, like most kids.

Instead, there was my father’s death, and its unsettling, disorienting aftermath, when within days my mum married a new man, Dean, and every detail about Dad was wiped from our lives. Even his picture was taken off the walls. There were some days when it could seem as if he’d never existed at all. Or, at least, that’s what the adults in our house appeared to want us to pretend. His money was still good, though. The family lived it up for a bit in Portsmouth, using his life insurance payout, which took us from a council house to a big fancy home and private schools. Then everything turned upside again in the blink of an eye.

It was never actually clear to me and my siblings what prompted the sudden move to another country. There was a feud of some kind between my mum’s and late dad’s sides of my family. We were mostly protected from it, but we could all tell that something was going on off stage. So perhaps that had something to do with it.

One cold, damp winter’s day when I was nine, my mum picked me up from school early in the afternoon. I was a bit surprised as she didn’t normally come at this time, so I asked her what was going on. She said, ‘Dean’s patio firm has burned down.’ She was strangely calm and matter of fact. Even at that age I was knocked a bit off balance by this.

‘What do you mean?’

‘It’s all gone, burned to the ground.’

We drove over to the factory. Cinders and ash were everywhere. The fire brigade had already been and so some things were only half-burned, just about standing. In the middle of it all was my stepdad Dean. He was clearly distressed, picking up horribly stained patio slabs and then throwing them down in disgust. He kept on saying, ‘All that work. All that work.’

Apparently there had been an electrical fault. With the business literally up in flames, Dean and my mum decided that when the insurance money came through, they would move the whole family off to rural France.

Portsmouth is a working city. It’s busy and vibrant, full of builders, bricklayers and scaffolders. And it’s as British as they come. Going from there to a small village in Normandy was a lot for us to take in. All of a sudden we’d swapped the densely packed bungalows and villas of England’s south coast for rambling open countryside. I’d been used to crowded cul-de-sacs, bustling high streets, the chatter of passers-by. Now we were surrounded by endless land, space and quiet.

Our new home was an ancient farm with a huge barn next to it. Dean threw himself into remaking the whole house, which was in a fucking state, almost a wreck. In those first few months while he tried to make it liveable, we slept and ate in caravans that were parked up in the barn.

That was when it all hit me. I remember asking myself: where did the good life go? How come we’re living in a barn? You can deal with change when it’s a question of moving two streets, even two towns, away. But starting your whole life again? That’s something else, especially when, like me, you’re still grieving for a dead father. There were other strange things that I couldn’t get my head around. We were eating pasta and sweetcorn for breakfast, lunch and dinner. I was being dressed in hand-me-down shoes and clothes from my brothers. And the adults were driving a shitty old car that occasionally would simply refuse to start. But on the other hand, the house Dean was working on was massive.

To begin with, this strangeness was compounded by the exhilarating freedom my brothers and I discovered in our newfound isolation. We’d moved in summer, and since Dean and our mum were so focused on getting things up and running, we were given the run of the fields around the house. Nobody told us what we could or couldn’t do. Even sleeping in a caravan was like an adventure after suburban Portsmouth.

And then it all came to an end. The threat of going to a French Catholic school had hung over us right through July and August, but we’d managed to shove it to the backs of our minds. I didn’t speak a word of French, not even stuff like bonjour or au revoir. We were also going to be the first English children to ever attend the school. New kids are always treated like they’re carrying a disease – surely the fact that we were foreign would make that even worse.

On the first day of school we were late – the fucking car wouldn’t start. I can vividly remember going into the classroom. I walked in and there was a moment of silence. Every single pair of eyes in the classroom bored right into me. The way those rows of kids were staring at me – it was as if I’d murdered somebody. My cheeks went red, but it was going to get worse. On the way in, once it had become clear that we were going to be late, I’d asked my two older brothers how to explain that we’d had the problem with the car. They told me, ‘Just say, “voiture kaput”.’ This would have been good advice, but what they hadn’t told me was that you have to pronounce ‘kaput’ as ‘kapoot’. If you say ‘kapot’, people will think you’re saying ‘capote’, which is a French word for condom.

I went into the classroom in the middle of a French lesson being taught by Monsieur Laurent, the headmaster, who was bald, with glasses and a polo neck – he looked as French as you like – and who ran the school along with his wife (because it was a Catholic school, the majority of the staff were nuns, something that added an extra layer of weirdness as I walked in). Madame Laurent was known as the good cop, while her husband was the bad cop. The tradition there was that if you were late, you had to stand up in front of the class and explain why. Schools are stricter in France, especially religious ones. I was dragged up in front of the blackboard, and then Monsieur Laurent spoke some words in French to me. I looked blankly back at him. I had no idea what he was saying. He repeated his question, in English this time: ‘Why were you late?’

That’s when I said the only French words I knew: ‘Voiture kaput.’ Except, of course, not knowing any better, I said ‘kapot’. The whole class burst into laughter, and I just stood there, bewildered, with no idea what was going on. Then Monsieur Laurent put me out of my misery and escorted me to my chair. I sat there humiliated and angry, and increasingly anxious about what was to come next.

It was the longest day of my life. Everything was strange. Everything was a challenge. Going into the playground that very first break time I found that I was an object of fascination. Most of the other kids crowding around me had never met anyone from England. This was La Manche, Normandy, a place where a lost cow or a surprisingly big chicken could end up as the talk of the town. It was two hundred miles in distance, and about a century in time, from Paris.

To them I was a freakshow. One minute they were all laughing at me, the next they were firing a million incomprehensible questions in my direction. One thing they kept asking me was if I wanted to play ‘babyfoot’. I now know that this means table football, but at the time I thought they were warning me that we’d be having baby food for lunch. So when it was time for the rest of the kids to go to the cafeteria, I just found somewhere to hide. Going hungry seemed to me a better option than cramming mush down my throat.

I remember crouching down, asking myself again and again, ‘What the fuck is going on?’

When we got back to our home later that afternoon I went straight to the den we’d made in the massive conifer trees at the bottom of the garden. I crawled in there in my school uniform and curled up, watching cars whooshing past on the main road from Caen to Saint-Lô, counting them, thinking, ‘How am I going to get through this? What is the solution?’

Ultimately, though, there wasn’t a solution. Or, maybe there was one, but finding it was way above my pay grade. My mum and stepdad might have been able to choose to go back, or change things up again, but I didn’t have that power. I was just a kid

What I realised was: you just have to go along with things. You’re at that school, whether you like it or not. You’re living in France, whether you like it or not. You’ve got to fucking adapt to it – or you crumble. If I didn’t get on with it, I’d have never gone back to school again. And it wasn’t like I could escape it for long; there were even classes on Saturday mornings. But if I couldn’t change the situation, I could change the way I perceived it.

In the process I developed a habit that has stayed with me to this day. The magnitude of the situation was so overwhelming that I could not possibly begin to understand it, although I did comprehend that there was a new man in my family’s life and that we were in a new country where they spoke a different language.

I remember thinking: don’t try to understand what you can’t. The only thing I could understand was myself. I began self-reflecting. I couldn’t control anything about being in France, I couldn’t change the sheer fact of our location, but I could look inside myself and see what tools I had to face the situation.

I say this to my children even now. ‘What makes sense to you? What can you understand?’ They’ll tell me what they can understand, and I’ll say to them: ‘Everything else, don’t even try. At this time in your life it’s too much to take in. Wait until you’re older.’

That’s what I did. When I couldn’t understand why my father had died so young and had been replaced so quickly by another man, I cut it out and focused more on myself. I could control what I was doing and feeling. You cannot expect to have the answers all the time, so why torment and confuse yourself by pretending otherwise? It will all make sense in time, when you’re ready. Don’t waste years of your life.

Sitting there, in my den, I asked myself: do you want to be that boy hiding from lunch every single day? Why not just embrace being that country kid? The moment you start fighting against it rather than looking for opportunities, that’s the moment you start to go under. I began to list my strengths and weaknesses to myself. I knew I was good at getting on with people, I was good at football (a handy thing for helping you fit in with other kids at the best of times, and even more so when you had no common language), I was resilient. These were all strengths I knew I could draw on and develop. But I couldn’t speak French and I didn’t have much leverage over my circumstances. These were both weaknesses. As I thought about it, I understood that while one of these could be fixed the other couldn’t. Just acknowledging that fact lifted a weight from my shoulders.

The next day I went into school almost without a care in the world. I stopped worrying and my attitude became far more, ‘Let’s just see how this goes.’ I went into lunch and realised that the food was actually decent, and went into what was called the foyer and found out what babyfoot really was. I played football in the yard with the other children and began to form a connection with them. My first and second days were like chalk and cheese.

I worked on the things that lay within my power, like getting to school on time, and I didn’t stress about the things that weren’t. I knew I wasn’t going to learn French overnight, so I didn’t allow myself to get dispirited by getting bad results to begin with. It wasn’t that I didn’t care; it was more that I was aware of what I could and couldn’t control, and so realised that there was no value whatsoever in beating myself up about stuff that wasn’t in my hands.