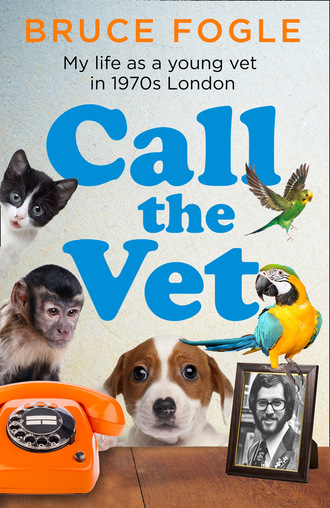

Call the Vet

Felicity Templeton-Ellis writes down her number and gives it to me then says, ‘How can I thank you? She means more to me than anything.’ And she embraces me in a whole body hug and holds me tight.

Is this what Brian calls ‘socialising with clients’? I walk her to and through the front door and return downstairs. Pat has placed Bianca in a cage and fed an oxygen line into it. ‘I’ll keep an eye on her and you can write up her notes, then I can write up her invoice,’ Pat says.

‘I’m impressed,’ she adds. ‘You may look like you’re fourteen but that was a job well done under fire. And fast. You should tell Mr Singleton you want to do more sophisticated surgery. And you’d like, what did you call it, halothane?’

‘Yes, halothane. By the way, who’s the owner?’

‘She’s part of the Clermont Set. Her husband is a notorious gambler. The Express says she is one of the most beautiful women in England.’

‘I noticed,’ I add with a smile.

I don’t tell Pat but I feel like a hero. I’m brilliant! I’m omnipotent! No one else could have done that. That dog would have died without me.

In 1970, that’s how I felt each time I saved a life. Now, with time and failures behind me, when I carry out a similar procedure there is satisfaction but with a far more profound feeling of humility. What I’ve learned is that when there are successful outcomes like with Bianca, and I make others happy, it can only lead to personal happiness and contentment. Success isn’t just good for your patients and their families, it’s just as important for our own personal happiness.

I kept Bianca upstairs in my flat above the consulting rooms over the weekend, on a bed of bath towels. These days, I’d keep her on painkillers for a week, but over fifty years ago we didn’t give pets much painkiller. We were taught that pain was a perception and only humans were capable of the abstract thought needed to perceive it. Bianca cried and moaned as I expected her to do after surgery. Background noise in the kennel room – it’s what all dogs did, though cats didn’t, and it took my profession much, much longer to accept that cats too feel intense pain. They just don’t vocally express it.

Bianca cried out each time I picked her up and carried her outside to the mews to let her empty her bladder. She lapped a little water on the Saturday evening but refused food until late Sunday, when she ate some Express Dairy sausage.

Today I lie on the floor with her. ‘Good girly,’ I tell her, and stroke her head. She looks up at me sadly, but then a tiny sparkle comes back into her eyes. I telephone Felicity with the good news, she comes to the surgery, picks up Bianca, and I arrange a home visit for Wednesday lunchtime.

‘You should have kept her here,’ Brian sternly tells me on Monday morning when I recount her injuries and surgery. His policy was to do all significant surgery, even simple dog spays, at the veterinary hospital built in the outbuildings of his home in Surrey. Every Tuesday, Brian transported all elective surgical cases in his Alfa Romeo Giulietta down to Limpsfield, operated all day Wednesday and hospitalised the dogs until they were fully recovered and had their stitches removed. If he performed an emergency operation at Pont Street, a ruptured spleen for example, he took that dog home with him that evening, and his Surrey RANA nursed it back to health.

Pet owners never saw the pain their dogs experienced after surgery. It took me some time before I fully questioned what I’d been taught, and started to use painkillers during and after not just surgery but any event that was potentially painful. When a canine parvovirus that caused acute gastroenteritis suddenly appeared nine years later, it was the dogs treated with painkillers together with more conventional treatment for serious gastroenteritis that were most likely to survive.

‘She’s walking on her own,’ Pat reports on Monday afternoon.

‘She went down the steps into the garden on her own,’ Pat reports on Tuesday morning.

‘She gave one of her toys a shake this morning,’ I’m told on Wednesday.

Isn’t it spectacular how dogs just get on with getting better, even after such pain and trauma? It impresses me as much today as it did then.

I had arranged to visit Bianca at lunchtime on the Wednesday, but ops took longer than expected and the afternoon was filled with appointments. I promised a quick visit to the nearby Wilton Arms, also on Kinnerton Street, to do a post-op check on their two cats I’d spayed on the Monday, so I asked Jane to rearrange the home visit for between 7.30 and 8 pm. After a pint with the publican, it wasn’t until just before nine that I got to Bianca’s sky blue painted terrace home off the Kings Road.

It is only when she answers the doorbell that I realise just how deliciously tall Felicity is, my height in her stockinged feet. In a short, dark skirt her legs are as long as Twiggy’s but her curves are pure Italian movie star.

‘Darling Vet. You’re such a sweet man to visit,’ she says, louder than I expect and kisses me on my lips.

‘It’s Bruce,’ I say.

‘Come in. Meet my friend Barbara. Stay. Have a drink? Have something to eat. Bianca is a miracle. A miracle! That fucking bastard Alsatian! I’ll kill him if I see him again. I’ll fucking castrate his owner. My husband will see to that. You’ve had such a busy day. I’m famished. Come in. Meet Barbara.’

Felicity’s eyes are extraordinarily beautiful, their aquamarine sparkle enhanced by pinhead-sized pupils.

‘Hi, I’m Barbara.’

Felicity’s friend, a fringed willowy brunette in matching white top and hot pants, offers her hand then kisses me on both cheeks.

‘Look at Bianca. It’s as if nothing’s happened to her. Isn’t she marvellous?’

Bianca is resting alertly on a white leather sofa, and I go over and sit down beside her. She flinches and pulls away as I reach out to touch her.

‘Hello, little girly. You’re quite a tough nut, aren’t you?’ I say and offer her a finger to sniff, and she does.

For most operations, the surgical site is shaved. We used a noisy electric Oster clipper followed by a men’s razor at Pont Street, but I’d worried that clipped hair might get inside Bianca’s chest so I’d just scissored away the long white hair from the edges of her wound. Once I’d sewn the skin back together, there wasn’t much sign of the trauma she had suffered. With her white hair covering her wound, I couldn’t even see her skin stitches.

‘What’s her appetite like?’ I ask.

‘She adores prawn cocktails,’ says Felicity, as she offers me a glass of red wine, spilling some as she fills my glass. ‘Oh, fuck. Do you adore prawn cocktails? You must be starving. I’m starving. You must eat. You must.’

‘Thanks, I’m okay,’ I reply.

‘No, you must. We’re going to Annabel’s. Please come. It’s my thank you for what you did for Bianca. You must.’

Barbara adds, ‘Do come. It’s much more comfortable having dinner with a man.’

‘Are you sure you’re happy to leave Bianca alone?’ I ask.

I can see that Bianca could safely be left but am looking for a reason to avoid ‘socialising with clients’, especially a married one.

‘Of course she is! Thanks to you!’

‘Will your husband join us?’ I ask.

‘Our husbands are shooting in Italy,’ Barbara replies.

‘Or something,’ adds Felicity.

‘I’m almost ready,’ Felicity tells Barbara, and she leaves the room, only to return a few minutes later. Her long blonde hair, parted on the left and previously in a ponytail, now flows over her shoulders. Her platform heels make her tower over me. The only likeness between Felicity and me is our similar age and language. Otherwise we are from different leagues and hers is a lot more professional than mine.

I worked in San Francisco in 1968, at a hippy vet’s clinic on Haight near Ashbury. Mort, my boss, would offer me a joint each lunchtime, and each lunchtime I refused with a ‘Thanks, Mort. I don’t smoke. Asthma.’ One evening, after dinner with two friends, Jinny his wife provided us with just-baked brownies for dessert.

‘Hash brownies,’ Mort explained after I’d eaten three of them. ‘Specially for non-smokers.’

That evening Mort and his friends minutely examined his Navaho woven-container collection.

‘Wow, look at that!’ Mort pronounced. ‘There’s a diamond-back rattler crawling around this one.’

I took the container in my hands.

‘No, Mort. That’s dark, dyed grass geometrically woven at a perfect 45-degree angle to make a symmetrical diamond pattern.’

I was too uptight to be affected, even by the concentrated THC drug in hash, but became familiar with its physiological effect.

Here in London’s Belgravia, looking into Felicity’s beautiful but now bloodshot eyes, I know that she is blown away on an industrial amount of it.

A Bentley car and driver mysteriously arrive outside her home and takes us to Berkeley Square. I am taken first upstairs to the Clermont Club, where Felicity and Barbara kiss seemingly everyone, then down a flight of stairs to Annabel’s for dinner.

The staff know both of them and we’re greeted with genuine smiles. There’s a table waiting and we sit down and drink. Then order. Then drink more. And eat. And we talk non-stop, but it’s so loud in the restaurant I don’t know if what I’m saying has anything to do with what Felicity is saying. I don’t mind because I’m having fun and I have two stunning women for company

‘Let’s dance,’ Felicity says to me between the main course and dessert and we do. She is a hugger. My love life is parched, but she is married and I am, you know, a Canadian.

When we return to the table, Barbara unexpectedly announces, ‘Felicity. Must go. I have a doctor’s appointment first thing tomorrow.’

She kisses Felicity goodbye and I see her lips say, ‘Don’t overdo it.’ Barbara kisses me goodbye and leaves, and we return to the dance floor.

‘Bruce is my vet. He saved Bianca’s life,’ Felicity says to a couple she obviously knows.

‘Hello!’ they greet me in unison, then continue dancing. Everyone seems to know Felicity, and their ease at seeing her with a man who is not her husband makes me feel more relaxed.

It is now after 1 am. I’ve always envied people who can live for the moment. I couldn’t then and still find it hard to do. As I’ve mentioned, Brian had told me not to socialise with his clients. And this one is married. I explain to Felicity that I have to be at work in a few hours and she gathers up her things.

The doorman hails us a cab and Felicity tells the driver to take us to her address and then 14 Pont Street. As soon as the cab pulls away, without a word she leans over and kisses me – passionately. Nice.

We drive around Berkeley Square.

She hold my hand and places it on her breast. Very nice.

The cab drives down Piccadilly, through the tunnel under Hyde Park Corner, past Harrods and down Beauchamp Place, and we keep kissing.

Then Felicity takes my hand from her breast and guides it to her knee and along her thigh onto velvet skin. She is wearing garter and stockings.

Our kissing becomes more ardent and she moves my hand further. When did you manage to rearrange everything that way? But then it dawns on me, No, it’s not rearranged! Felicity, do you know that between there and there your knickers have no knickers?

‘You have reached your destination,’ the cabbie announces.

Maybe not, but we are parked outside Felicity’s home and we both sit back in our seats.

She opens her handbag and gives me a crisp £20 note.

‘Pay the cabbie when he drops you home,’ she says, then, ‘Mmmmm’ and gives me a last long kiss and leaves the cab.

‘Got anything smaller?’ the cabbie asks when we arrive at Pont Street and I proffer the £20 note. I think, I have now, but don’t say it. When I see Felicity the following week, to remove Bianca’s stitches, I give her a £20 note and explain she had given me too much for the cab. Felicity has no recollection of giving me the money but from the look in her eyes remembers the rest of the evening. Bianca still doesn’t want me to touch her.

I ask Christopher when he next visits with a litter of Pekingese pups if he knows of the Templeton-Ellises.

‘Felicity Templeton-Ellis is very alluring,’ I remark casually.

‘She may be moreish but avoid her with a barge pole,’ he cautions. ‘It doesn’t matter how charming she is, he’s ex-SAS and provides mercenaries for African dictators. Mostly former Foreign Legionnaires. His best friend Lord Lucan has just separated from his wife. They’re both heavy gamblers at the Clermont Club. Ruthless. Completely ruthless. Brian pales into insignificance in comparison.’

‘You’re comparing Brian with the SAS?’ I ask incredulously.

‘Aren’t you as frightened of Brian as I am?’

I say that I am intimidated by Brian but also see that he behaves as he does because he exemplifies the reserved Englishman.

‘There’s someone inside who wants to get out and have fun,’ I remark.

‘Well, all I see is a perfectionist who frankly I find quite scary,’ Christopher says. ‘And what’s scarier is that tomorrow I have to take one of these bloody Pekes on a Swissair flight to Geneva, and I hate flying!’

‘Okay, Christopher,’ I reply. ‘I have two questions: why don’t you like flying and do people actually pay your airfare for you to personally deliver pups to exotic places – because if they do, I want to swap jobs with you.’

‘I hate flying because I feel claustrophobic in planes, and yes, we provide a door-to-door service if that’s what our customers want. This one here?’ and he lifts the pup in his left hand. ‘I’m delivering it to Yul Brynner in France next Friday.’

‘Right then, the pub after work? I’ve got more questions and I owe you.’

We meet as arranged at 7 pm at the Nag’s Head.

‘There’s a charity gala event in Belgrave Square this evening and I’m taking my girlfriend to it. British Red Cross. So just one drink,’ Christopher explains.

Inside it is heaving as always, so once more we take our drinks outside.

‘Do you seriously hate flying?’ I ask.

‘Everything about it. Going to Piccadilly to buy the bloody ticket. Checking in at BEA in Victoria. The coach trip to Heathrow. Walking across the tarmac. Climbing those rickety stairs. Finding myself incarcerated in a sardine can without a bloody can opener. Going through bloody Customs. Filling in the bloody tax forms because I’m importing goods. The bloody French. I hate it all.’

‘So why don’t you have one of your shop or kennel staff do the deliveries?’

‘Because our customers want mother to deliver their pups, and if it’s not mother then it’s me. That litter of Pekes I brought in today? Royalty. Singlewell Pekes. And royalty have their own chauffeurs. The mother of that litter was a debutante at last year’s Crufts. Are you going to Crufts? Dog royalty. You should. It’s not simply a dog show, it’s the start of the London Season.’

‘The London Season?’ I quiz.

‘Bruce, you must go. It’s the doggy equivalent to the Debutantes’ Ball. Bossy women and moustachioed men. Only those with aristocratic credentials – they’ve won best in their class – are eligible to attend. Fresh-faced virgins displayed not just to eligible bachelors but to professional seducers. Parents choosing who will mate with whom. Stagey pomp. The participants all nervously eyeing each other. It’s absolutely hideous and wonderful all at the same time.’

‘But you said it’s the start of the London Season. What’s that?’ I ask.

‘Bruce, to understand the British you need to know what makes us tick. I’m sure just as I do you meet some wonderful people, but we also meet people who are utter snobs, who go to events because it’s what aristos have always done. Go to Crufts. You’ll see more ex-Colonial officers and their wives and retired colonels and their wives than anywhere else in Britain, unless of course you follow them through the London Season, to the Boat Race between Oxford and Cambridge on the Thames, then the Summer Exhibition at the Royal Academy and the Chelsea Flower Show, Trooping the Colour, racing at Royal Ascot, the Proms at the Royal Albert Hall and if you are willing to move up the Thames a little, to the Henley Regatta.’

Christopher laughs. ‘Do you think they see the irony of an aristocratic event sponsored by Pedigree Chum?’

Before I can get a word in, Christopher adds, ‘Listen, Bruce, must leave. That Peke pup I’m delivering to Yul Brynner on Friday? I’m taking my girlfriend with me. He lives at Le Manoir de Criqueboeuf about ten miles from Deauville. He’s always sending us photos of his Pekes with his children. We’ve sold three to him. I’ve booked a hotel for Susannah and me in Deauville for the weekend, and I’m hoping we might be invited to his chateau for a meal. I’m picking her up now, then we’re off to the Red Cross fundraiser in Belgrave Square. Why not grab a girl and join us there? But not Felicity Templeton-Ellis.’

Grab a girl? That was like, ‘Why don’t you fly to the moon?’

I did wander over to Belgrave Square. It’s minutes from Kinnerton Street. The railings around the gardens had just been replaced. They were removed during World War II when the gardens were used as an Army vehicle compound. I felt out of place, on my own. I looked for Christopher, but in the thick crowd didn’t see him. An artist, Feliks Topolski, was sketching people, with his fees going to the Red Cross. I sat for a sketch. Seventy-five pounds. Almost four weeks’ salary. Still have it.

* Pethidine is a narcotic painkiller. It’s still used sometimes but was succeeded by methadone.

† Curare (from a tree bark) was used on arrow tips by South American people to paralyse prey. It works by paralysing motor nerves. Synthetic drugs were developed to do the same.

5

It was July and London was sunny, although the mood in the country sure wasn’t. I was on a decent salary for the British, £21 a week when the basic wage was £11. But dock workers had called a national strike and the Queen, who had been visiting Canada, signed a State of Emergency within ten minutes of landing back in London.

There was a surly feeling in London. Lots of talk of ‘us’ and ‘them’, lots of national strife, but even so this was the best time ever to be a vet. That’s because my profession was on a cusp. I was trained as an animal mechanic, but I already had a hunch I should be more than that. The equipment at my disposal was just starting to improve in capability. We were about to be the first clinic in London with an electrocardiogram (ECG) machine, although that depended on the strike ending and supplies coming through the ports once more. There were a few specialists around, but a vet like me was still a jack of all trades, expected to handle any animal emergency. I was able to do things my professional liability insurers would never let me do today.

‘Bruce, St George’s Hospital just rang. A horse has been injured by a lorry outside the hospital and needs help. Brian wants you to go.’

It is lunchtime and I am reading the ECG section of Canine Cardiology, one of the American textbooks I brought with me to London.

‘Do you know how bad it is?’ I ask Pat.

‘The horse is standing and has a large flesh wound to its shoulder. That’s all I know. It’s probably one of Lilo Blum’s. Her stables are in Grosvenor Crescent Mews.’

‘Does Brian know I’m allergic to horses?’ There’s a hesitation in my voice.

‘You mean you don’t like treating horses?’ Pat queries.

‘No, I mean I’m allergic to horses. They make me seize up.’

‘How did you get through college, then?’ she asks.

‘With friends covering for me.’

‘Don’t forget the bute. It’s in the fridge,’ Pat reminds me.

I packed my medical bag with Betadine,* a new skin antiseptic we had just purchased, developed by NASA for the recent lunar landings, xylocaine cartridges and the cartridge gun, a spool of autoclaved surgical silk ready for use, a selection of sterilised surgical needles, a surgical pack of forceps, needle holder, scalpel, scissors and swabs, the phenylbutazone, or bute, a painkiller and ACP, a sedative, in case the horse was difficult to manage.

‘Did the knife-sharpener sharpen all the scalpel blades and scissors?’ I ask.

‘Yes,’ says Pat, ‘and Mr Singleton has ordered new, disposable blades, so we’ll be hearing less bloody grinding from that sodding cart in the future.’

At a brisk walk in a fresh autumn wind it took less than five minutes to get to St George’s, where the injured horse was standing on the crescent-shaped ambulance entrance, surrounded by a crowd. There were several girls in nurses uniform in the throng. All of them looked gorgeous, even the ones who probably weren’t.

A ginger-bearded man, blue-green eyes, my height – a little over six feet tall – and my age – late twenties – wearing an olive-green tweed hacking jacket, tan riding breeches and brown boots, was holding the reins and halter. He looked great. I was envious.

‘Hi, I’m Bruce Fogle, the vet. How’s the horse?’ It is a little Arab-Welsh grey pony.

‘I’m Jeremy Livingston and this is Euripides. He’s surprisingly relaxed considering what has happened to him. I ride Euripides at lunchtime each day. He’s immune to the traffic but today, as we turned into Hyde Park Corner towards the park, for no reason at all he came to a full stop. He has never done that before. The traffic stopped, but then a lorry tried to go around us and caught him on his port side. It looks rather angry, and so am I.’

By now, between working at the zoo and for Brian, I had been in London for almost a year, was getting more familiar with British understatement, and I liked it. It sat well with how I felt. I walked around to Euripides’ left side and saw the damage, a raw, ragged skin tear about fifteen inches long, with many red trails of both dripping and drying blood running down his leg. Fortunately, there was minimal muscle damage under it.

‘Nasty,’ I say to the rider. ‘Jeremy, are you his owner?’

‘Yes. I stable him at Lilo Blum’s.’

‘Do you have your own vet?’

‘Yes, Mr Eaton. In Sutton.’

‘Before anything else, I want to give Euripides some painkiller,’ I say. I get the bute from my bag, raise his right jugular vein and inject a few millilitres of it.

‘Is Mr Eaton on his way?’ I ask.

‘I have had people ring from the hospital but they can’t get hold of him. Will you please take care of the wound?’

‘Yes, of course,’ I say.

So far so good. In a horse stables, thanks to my allergy my lungs would have sounded like bagpipes by now, but outdoors at Hyde Park Corner they produce no whistles and breathing is easy.

Euripides is an experienced urban pony, wonderfully relaxed, so I don’t use the ACP sedative. Pat’s grinning advice as I left the surgery – ‘If the horse is a male and you use ACP, remember you’ll probably have to carry his penis back slung over your shoulder’ – influences my decision to avoid it. ACP relaxes the muscles that keep a horse’s penis where a horse penis should stay.

While Jeremy holds Euripides by his halter, I cleanse the tear with Betadine. On the upper edge of the laceration, one region of skin is raised and rounded. I feel both sides of the mass and it’s as if a pellet has lodged just under the skin. I squirt xylocaine over the open flesh, then inject the surrounding skin, including on the far side of the pellet. On dogs I usually use about half a cartridge of xylocaine. Euripides needs six cartridges.

‘How old is Euripides?’ I ask.

‘Fifteen this month.’

The hundred-yard spool of sterilised surgical silk is in a separate autoclaved bag, but as I open it the spool unexpectedly rolls out, not onto relatively clean pavement but into Euripides’ fresh green manure. I am surrounded by a crowd of onlookers. I’ve dropped my suture material in horse poo. Can you imagine how I feel?

‘Damn!’ I mutter under my breath, but before I even think of asking someone to go back to Pont Street for more, one of the pretty nurses steps forward and says, ‘Would you like me to get you some suture material?’