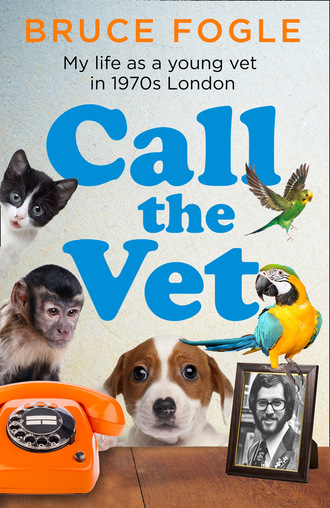

Call the Vet

‘Vet is having tea,’ he replies.

‘Thanks,’ I say, ‘I’ll come and have a look now.’ I pick up my medical bag and walk down the corridor to a large wooden crate with rope handles. There is no door.

‘How do you open it?’ I ask.

‘The top is nailed shut so they can’t escape,’ the Manager says. He is carrying a claw hammer and, with the claw end, pries off the top. There is silence from inside the crate.

I look in. One pup sits up and unhappily looks at me. Another, with its hair pasted to its face by its own profuse saliva, lies on its side, glassy eyed, panting and drooling. A third pup is twitching and salivating. The rest are lifeless.

I pick up the sitting pup, give it a cursory look and hand it to the Manager. ‘Put it somewhere with water.’

Without looking at her I say to the shop assistant, ‘Get two of those fabric dog beds from the floor.’

I pick up the salivating pup and with my stethoscope listen to its chest. The heart sounds good. I listen to the twitching pup’s heart. It sounds the same. I lift a lifeless pup and listen to its chest. No breathing or heart sounds. Then the next pup. It has a heartbeat. So does the next. So do all the rest. Only one is dead. I guess this is probably a low blood sugar crisis.

The shop assistant returns with the round fabric dog beds. The Manager places the healthiest pup in one of them.

‘Do you have any maple syrup or honey for your tea?’ I ask the Manager.

‘I don’t. But they do in the Food Hall. Come with me.’

I turn to the shop assistant. ‘As fast as you can, run to the surgery, ask them for a vial of 50 per cent glucose and get back here, to wherever honey is in the Food Halls.’

‘The surgery is on Pont Street, the other side of the lights,’ the Manager adds.

I pick up the bed full of unconscious or frothing pups and follow the Manager across his department. He quick marches.

‘Faster!’ I shout and he moves from a brisk walk into a run, down the flights of stairs to the ground floor, through Menswear and into the Food Halls, straight to a selection of honey.

I take a jar from the display, open it, give it to the manager and say, ‘Dip your finger in it and smear it in the mouths of the conscious pups.’

I take another jar and do the same with the unconscious pups, applying honey under their tongues and inside their cheeks.

‘Animals are not allowed in the Food Halls,’ I hear over my shoulder.

‘These are not animals!’ the Manager barks back. ‘They are Harrods inventory!’ No one seems upset that I have taken honey from the shelf without purchasing it.

It amazes me how fast sugar gets absorbed from the mouth into the bloodstream. The pups are small. They have little or no sugar reserve. They had been enclosed in a wooden crate since sometime in the early morning somewhere in Wales for a long, hot train journey to London before another hot ride in a taxi to Knightsbridge. I am burning with anger at how these pups have been treated, but I don’t say anything.

The shop assistant arrives with the injectable glucose vial. I break it open and fill the syringe I have brought along to give vaccinations with, add a sharp new needle, place my finger on an unconscious pup’s throat to raise its jugular vein, insert the needle and inject one millilitre of the concentrated sugar. Within a minute, the pup is moving and within five minutes sitting up. I do the same with the remaining two pups that have not responded to honey under their tongues. Both come back from the dead.

‘Get me a towel, please,’ I ask the Manager’s shop assistant, and she instantly produces a tea towel. I give the brightest pup a rub then place it on the floor, where it gives a little shake that is too much for it and it sits down. I repeat the rub downs with the other five pups, and when I am convinced that their low sugar crisis is at least temporarily over, I put them in the dog bed and return with the Manager and his assistant to the second floor, this time by the lift.

‘Oh, aren’t they cute,’ the lift operator says as we get in.

We return to the Manager’s office.

‘I’m sorry, I don’t even know your name,’ I say to him.

‘Grimwade,’ he replies. ‘And this is Miss Clark.’

‘Annabelle,’ she adds.

In the corridor, the bed in which we placed the unharmed pup is empty when we return.

‘Miss Clark, find that puppy,’ Grimwade tells his assistant, and as he does so the pup scampers out from under his desk with a piece of wrapping tissue in its mouth.

I speak to them. ‘Annabelle, please give that one a little honey with its dog food. Mr Grimwade, I’m taking these pups back to the surgery for the rest of the day. I want to make sure they’re over their crisis. They shouldn’t be left alone tonight.’

‘Mr Grimwade, if you can arrange for a taxi I can take all of them home with me tonight. I can stay up with them,’ Annabelle adds.

‘We shall see,’ he says.

‘That’s a terrific suggestion, Annabelle. Thank you very much. That’s what we’ll do. Mr Grimwade, considering the amount of money Annabelle saved Harrods with her Olympic-standard run to Pont Street, I think you can afford to provide her with the taxi fare home and back. I’ll discuss the events with Mr Singleton, then give you written advice on where Harrods should get its puppies and kittens, how they should get here and what to do when they arrive.’

‘I look forward to that, Vet,’ Grimwade replies.

I think about asking him out for a drink that evening. I already know what I want to change in his set-up, but remember that Brian has told me no socialising, so I don’t.

Back at the surgery, late in the afternoon, Brian calls me into his office.

‘Bruce, may I introduce you to Mrs Jane Grievson from Town & Country Dogs and her son Christopher.’

Each has two Shih Tzus in their arms, a breed I have never heard of, let alone seen.

‘Good afternoon,’ they reply in unison.

Mrs Grievson has immaculately permed, bottle-blonde hair, is petite and vivacious, younger than my mother, an English rose whom I am instantly frightened of. Christopher, my age but more heavy set and a little taller, a man with an artlessly happy face, tickles the pups in his hands as his mother speaks.

‘I was just thanking Mr Singleton for sending me to Mr Startup in Worthing. I was considering buying a new toy Poodle as a potential stud, and wise Mr Startup asked me to bring the pup’s grandmother for him to examine. He found eye disease in the grandmother that he says is hereditary and leads to blindness, so I did not purchase the pup.’

Brian turns to me. ‘There are no eye specialists at the Royal Veterinary College, but Geoff Startup in Worthing is very knowledgeable about eyes and sees referred cases.’

‘And I was also telling Mr Singleton that you will be seeing more of Christopher,’ says Mrs Grievson. ‘My husband Bob and I enjoy dabbling in property. We have an old mill in Italy we are about to fix up.’

‘Yes, I’m afraid so,’ Christopher adds. ‘Mother has convinced me to join her permanently. Bruce, have you visited our shop?’

I tell him I haven’t and agree to visit after I finish the afternoon appointments.

‘What type of pups are they?’ I ask before I return to my list of clients, and I am impressed that Christopher answers before his mother can.

‘They are Shih Tzus. Very rare. Oriental. We get them from a breeder friend of my mother’s in Trevor Square.’

‘We sell oriental breeds but we don’t sell breeds to Orientals. They treat their dogs abominably!’ Mrs Grievson adds.

Early that evening I walked up luxurious Sloane Street then left onto Hans Crescent. Town & Country Dogs was the second shop on the left, although its address is 35B Sloane Street. I assumed that Mrs Grievson managed to secure a better address because other people found her just as scary as I did when I’d met her a few hours earlier. I felt more relaxed when Christopher told me she had gone for the day and suggested that after a quick look around we go to a local pub for a drink.

The shop was elegant and feminine, with pastel, floral wallpaper, dark wooden floors, hanging lace in the north-facing windows that were set up for litters of pups to be displayed in and a pendant light fitting of smoked glass. Christopher takes me downstairs to see the pups’ holding kennels and their clipping, washing and grooming facilities, then we walk over to the Nag’s Head on Kinnerton Street, a mews street five minutes away.

‘Have you been here before? It seems a suitably named drinking hole for a veterinary surgeon,’ Christopher chuckles as he steps aside to let me enter the tiny, dimly lit, packed pub. The Nag’s Head is simply a tiny mews house, no more than 15 feet wide, on a narrow lane, surrounded by private homes. It’s like walking into someone’s small, dark-panelled living room, 15 feet of standing room in front of a bar with stairs going down to the left and stairs going up to the right. The walls are densely covered in framed cartoons and art. I instantly fall in love with the place and decide that this will be my ‘local’. I have a Carling Black Label, and we take our drinks outside and find room to stand between two parked cars in front of the pub. I had already learned during the shop tour that Christopher has the ability to speak so loudly and so fluently there are virtually no pauses where I can ask any questions.

‘How did your mother come to set up Town & Country Dogs?’ I spot an opportunity and Christopher embarks upon a resumé of his mother’s life. Earlier that day, I had pigeonholed him as his mother’s gofer. Now I hear the pride in his voice as he tells me the back story of the pet shop.

‘My mother is not your typical British dog breeder. Much too glamorous.’

I’m relaxed with Christopher, so I ask, ‘What’s a typical British dog breeder?’ and Christopher says, ‘A woman who reached marriageable age just after World War I, found there were no men left to marry and so has devoted herself to dogs. Do you know Betty Conn Ffyffe? Wonderful woman. Enormous. Ever so loud. Only wears tweeds. Monocle. Barks ferociously. If a dog is reluctant to perform she shouts, “Pull yourself together,” wanks it until it’s blue in the face and two months later Mother has another litter to sell.’

I sip my ale and let his riff roll on.

‘Mother has been breeding Poodles and Yorkies for over twenty years. After the War, her family – she lived in Kent – had nothing. She knew dogs and started out making clothing for them. Very upwardly mobile, she was. Mother saw that no one was catering to the top end of the market. She managed to convince Tatler to give her an enormous picture spread. That made her, her shop and her dogs well known to society. That’s why we are around the corner from Harrods. Mother breeds most of the dogs she sells. She has an enormous facility in Cornwall. Or she knows breeders personally. But Bruce, you know what has really made the business so successful? Hollywood loves her. Simply adores her. They love her energy, her theatricality. Cary Grant or Ethel Merman or Elizabeth Taylor come into the shop and they think they are in an Edwardian film set, which is exactly where they are. We still can’t find enough good Old English Sheepdogs for the Americans.’

‘Is that why Harrods always has Old English Sheepdogs?’ I ask.

‘They get theirs from breed-to-order hill farmers in Wales. Dreadful places. Riddled with parasites. The pups don’t meet a soul until they’re put on a train to London.’

‘Why Old English Sheepdogs though?’

‘Because of Doris Day and David Niven and their Old English,’ Christopher replies. ‘In Please Don’t Eat the Daisies, the film. It might be ten years old now, but it started a craze in America for Old English.’

‘Did your mother supply the dog for the film?’ I ask.

‘It wouldn’t surprise me, but I’ve never asked,’ Christopher answers. ‘Mind you, if she did, they would have had to pay for it then and there. Mother has very firm rules. No one is given extended credit, not President de Gaulle, not Princess Grace of Monaco.’

‘They buy dogs from you?’ I am impressed and wonder whether I’ll meet them at Brian’s.

‘Yes, and they were not allowed to leave her shop until they paid for them. In full. In cash.’

‘I’m trying to convince Brian to accept payment with Barclaycard,’ I say, and I pull out of my pocket my Chargex credit card issued by my Canadian bank. ‘It’s identical to this, right down to the colours. Brian says it’s only for shopping in department stores, but vets in Canada get paid this way and the card holder is liable if someone else uses it.’

‘Too technical for mother,’ Christopher replies. ‘Cash rules.’

* The vaccine came with a two-inch serrated saw, to abrade the necks of the vials to make them easy to snap open. I routinely cut my fingers when snapping vaccine vials so I also took finger plasters for myself.

4

I talk with Brian about the low blood sugar Yorkies at Harrods and he asks me to give him in point form a short list of recommendations. With help from Christopher, I list:

Wormed pups from reliable sources

Bred for physical health

Checked by breeder’s vet before dispatch

Open kennels for travel, accompanied by a person

No crowding

Sugared water available during transit

Seen by us when arrive at Harrods.

Brian approves the list with one alteration:

Seen by us at Pont Street before arrival at Harrods.

He asks Pat to flesh out each point into a single sentence, make two carbon copies and bring them to him for his signature. ‘It’s best that this letter comes from me,’ he explains.

I tell him how good Annabelle the shop assistant was, and he says, ‘Keep an eye on her. I think Jane is pregnant, and if she is we’ll have to look for a new junior RANA.’

In the 1970s, pregnancy often meant you lost your job.

In the following weeks, I continued to do around twenty to twenty-five consultations each day, mostly dogs but some cats, a few birds and the occasional monkey or snake. At that time, I was too preoccupied with whether or not I was making accurate diagnoses to notice much about the owners, but I was aware they were mostly women and regardless of age almost invariably tall and well dressed. When I became more familiar with Britain’s social orders, I realised that Knightsbridge acted like a magnet for tall, thin women. I imagine it still does.

I’d also noticed that we saw a large number of elderly Poodles owned by over-made-up, fleshy women, mostly in their late forties or early fifties.

‘Those dogs can thank the Street Offences Act for the good lives they lead,’ Brian tells me when I ask why Poodles had once been so popular.

‘How’s that?’ I ask.

‘The Act made it an offence for streetwalkers to solicit for business in public places. So the girls equipped themselves with Poodles. The dog’s colour indicates the service its owner provides. They’re mostly Shepherd Market Poodles. That’s part of our catchment area.’

‘So would you call them working dogs?’

Brian grinned.

My relationship with Brian was very much employee and employer. My instinct was to joke about what Brian had told me, but I didn’t think I should so I didn’t. In fact, I never relaxed enough with Brian to joke or make small talk with him about anything much. To a fresh grad like me, Brian was intimidating, more like a father figure you always wanted to prove yourself to.

Brian did all the complicated surgery, leaving me with mostly cat spays, dog and cat castrations and wound repairs, although I also did emergency ops and fortunately for me we saw lots of emergencies when Brian was out of the surgery. His responsibilities as Junior Vice-President of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons were extensive, so Pat and I met all the pharmaceutical company trade reps. I was obliged to stay at the surgery most nights and alternate weekends to take telephone calls and see any emergencies. If I wanted to go out in the evening, I arranged with the Post Office telephone operator to answer calls to us and refer them to Keith Butt, a vet in Kensington.

A nurse joins me in the surgery on Saturday mornings, and it is Pat rather than Jane or Brenda who is on duty when a distraught women bursts in with her rag of a little dog cradled in her arms.

‘Oh god, she’s been attacked by an Alsatian! Please! Help!’

I am sitting on the corner of the reception desk idly talking to Pat and can see visible flesh in the Maltese’s chest. I take my stethoscope from my neck to listen to its heart but before I have a chance to do so, Pat takes the dog from the woman.

‘I’m just taking her downstairs.’

I follow her down.

‘Turn on the oxygen,’ she tells me as she opens the dog’s mouth, inserts an endotracheal tube into its windpipe and blows into it. I watch candy floss pink lung tissue inflate and bulge out of the torn chest.

Pat continues to blow into the tube until I have oxygen flowing through anaesthetic tubing and she can breathe for the little thing by compressing an inflated anaesthetic bag.

‘Now you can listen to its heart,’ she tells me, and I do. It’s beating perfectly.

‘Where is Mr Singleton when you need him,’ she says, more I think to herself than to me.

I feel stupid, reaching for a stethoscope rather than doing something to save the dog’s life. Pat, the instinctively good nurse, doesn’t comment on my foolishness. I examine the ragged wound and see that one lobe of lung is punctured and damaged beyond repair, but the others on the injured left side are untouched. Two ribs are broken. It is the dog’s own rib that damaged her lung, not the Alsatian’s teeth. Pat continues to inflate the dog’s lungs by compressing the oxygen bag, but now with oxygen in her circulation she regains consciousness and is trying to get up.

‘Add ether,’ I tell Pat, and she opens the valve on the anaesthetic machine to run the oxygen through liquid ether. She opens the valve on the nitrous oxide cylinder and adds that gas to the mix. That settles the dog into anaesthetic unconsciousness.

‘Give her pethidine,’ I tell Pat.* Pethidine will lighten her breathing.

I tell Pat to continue ‘bagging’ the dog – inflating its lungs for it – while I prepare a tray of surgical instruments, and as I do we hear the telephone ring in reception.

‘Everything’s fine down here,’ Pat calls through the closed door. ‘Can you please answer that and get the caller’s telephone number?’

‘This is what’s called on the job training,’ she says, as I carefully cut away the little Maltese’s long white hair that has been sucked into its chest and prep the surgical site. If the dog is to survive, I have to remove two ribs and one lobe of lung, sew off the air passage and lung tissue so that there is no leakage of air whatsoever, then sew up the chest wall air-tight, coordinating the last stitches going in with Pat inflating the repaired lung back to its maximum.

‘I’ve done this before,’ I say.

‘Never!’ Pat replies. ‘At the zoo?’

‘No. We had surgical exercises at college. I’ve done one of just about everything.’

As I scrub up, the Maltese’s owner puts her head around the door to the prep room.

‘May I come in? Is she all right?’

‘She has dreadful injuries, but Dr Fogle is familiar with the surgery she needs and he’s just about to start. If you can answer the door and the telephone, I can stay with her. Right now she needs me to help her breathe. This is Bianca, isn’t it?’

‘Yes, it is,’ the owner says.

‘Mr Singleton spayed her last summer. She’s a sweety.’

‘And you’re Felicity Templeton-Ellis?’ Pat asks.

‘What a good memory you have.’

‘Well, I do read the papers.’

My interest and competence in surgery had been honed back in Canada by Jim Archibald, my professor of surgery, who co-authored the textbook Experimental Surgery and edited the first surgery text for small animal vets, Canine Surgery. He was the dominant personality at the Ontario Veterinary College, and the curriculum committee gave him extensive time for his students to perform ‘surgical exercises’.

He chose his favourite students, and I was one of them, to work their final summer at the College as salaried employees performing experimental surgery – taking a dog’s kidney from the abdomen and transplanting it into the neck, opening a sow’s belly then her womb, then her unborn piglets, punching holes in their diaphragms then sewing everything back together so that human obstetricians could try to keep the piglets – born with the equivalent of torn diaphragms – alive long enough for full-time surgeons to arrive to save them. I never thought about the welfare of the animals I was experimenting on, only the challenge of operating successfully.

For surgical exercises, each group of four students was given a dog and a sheep to operate on in alternate weeks. We would open the dog’s abdomen – a ‘laparotomy’ – then sew her up, let the incision repair, then two weeks later do another laparotomy but this time remove her spleen then sew her up, play with her for another two weeks, then open her up again, open and close her bladder, then sew her up once more. As long as the dog survived we kept operating on her, removing a section of her intestines, or a kidney or a lobe of lung. If you think that what I was doing was barbaric, all I can do is utterly agree. What makes be shiver as I write this is that the welfare of these poor, innocent dogs never even entered my mind, or as far as I’m aware, the minds of my classmates. Most of us were men – only three women were accepted each year. Most of us were off farms or ranches, and those of us who weren’t, including me, didn’t have the basic thoughtfulness to question what we were doing. We wanted our dogs to survive to the next operation, to prove to Professor Archibald we were proficient surgeons. Being given a replacement dog was a sign of failure. What does that say about human nature?

I’m not saying that veterinary students should not practise on live animals. I am in favour of surgical exercises where a dog that is going to be killed because no one wants it is anaesthetised and operated on, then immediately killed without regaining consciousness. Today, I wasn’t ‘learning on the job’ when I was confronted with the difficult surgery that Bianca needed if she was to survive. I had learned to do a lobectomy and rib resection on a stray dog that no one had a continuing emotional investment in. But I still don’t fully understand why throughout my training as a vet I never once considered the welfare of the defenceless animals that I did surgical exercises on. They must have been family pets. Had they got lost? Were there families somewhere wondering what had happened to their dogs? How did the dogs feel? What did the dogs feel? It’s just horrific.

Bianca’s surgery is uneventful. We don’t paralyse her breathing with curare-like drugs,† something we did during surgical exercises, simply because we don’t have these drugs at the surgery. That means Pat coordinating the compression of the anaesthetic bag in synchrony with Bianca trying to take a breath herself. The challenge comes when we turn off her ether. The narcotic effect of pethidine keeps her breathing light, but even when she groans and screams, the stitches hold and her lungs remain inflated. By now the air in the operating room is heavy with ether that has seeped from Bianca’s torn lung.

‘We really should use halothane,’ I say to Pat. That’s the new and much safer anaesthetic gas we used at college.

‘Tell Mr Singleton,’ she replies.

While Pat wraps Bianca’s chest in gauze bandage, I go upstairs to reception.

‘She’s not out of the woods yet, but so far so good,’ I say to her owner.

‘Can she come home?’

‘Not today. I’ll keep her with me upstairs over the weekend. I’m on call anyways. Give me your number and I’ll call to give you progress reports.’