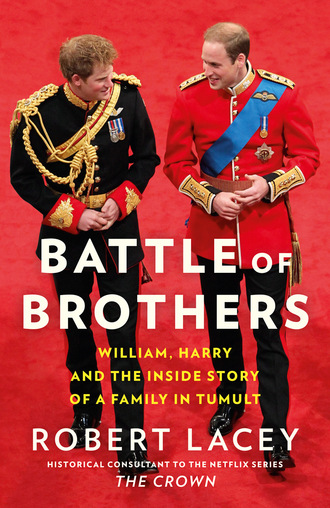

Battle of Brothers

In 2020, a Silver Cross Balmoral pram, complete with huge curved springs and wire-spoked wheels, will set you back £1,800 – and if that is a little too rich for your pocket, you can slum it with the lesser Kensington model at just £1,500. These prices come from John Lewis – to this day the Middletons’ favourite store, motto: ‘Never Knowingly Undersold’.

‘We all thought Dorothy was a bit of a snob,’ recalled Ron’s niece, Ann Terry, who worked beside her in a jewellery store. ‘She always wanted to better herself.’

Living upstairs in their cramped and unheated Southall flat that lay under the Heathrow flightpath, the Goldsmiths had to manhandle their Silver Cross perambulator up and down the staircase every time baby Carole needed some air.

‘My grandmother used to grumble about Dorothy,’ remembered another relative, ‘because she thought she henpecked her Ronald. She thought Dorothy always wanted more and more money. She wanted to be the top brick in the chimney.’

After a dozen years of marriage, Dorothy and Ron were finally able to move out of the council flat to their first proper house – in Kingsbridge Road, Norwood Green, near Ealing, at the smarter end of Southall. By now Carole was about to enter her teens, but she only attended the local state school and then left when she was sixteen, since Ron could not afford to send her to teacher training college. Carole went straight out to work for ‘the Pru’ – the Prudential Insurance Company in Holborn.

The Pru and Carole Goldsmith did not get along. She had never seen herself working in an office, so she asked her father to stake her for two more years at school to get her A-levels – economics, English literature, geography and art. These helped her to win a place on the coveted retail trainee scheme of where else but John Lewis, learning her shopkeeping in the china and glass department at the Peter Jones branch on Sloane Square, Chelsea. Carole was loving the idea of a career in merchandising, until she was instructed to knuckle down for a full six months as a sales assistant on the shopfloor.

‘Blow that!’ she said in 2018 in an interview with the Telegraph. ‘I’m not doing that for six months – it was really boring.’

No office and no shopfloor for Carole Goldsmith! Still aged only eighteen in 1973, she used her Pitman shorthand to get a job at BEA – British European Airways, just merging with British Overseas Airways Corporation to become the modern British Airways – and she also brushed up her schoolgirl French to secure a position with the ground staff. There she met the handsome and genial Michael Middleton, somewhat less forceful than her, but working in a quietly responsible job as a flight dispatcher, sharing with the pilot legal responsibility for passenger safety of the flights he supervised. The couple soon fell in love – and Lady Dorothy thoroughly approved.

Michael Middleton was exactly the sort of husband that Carole’s mother had hoped her daughter would snag – charming, good-looking and rolling in class, plus a bit of money. The Middletons could trace their descent to Tudor times, while their money went back to Yorkshire wool production during the Industrial Revolution. Shrewdly invested through a variety of trusts, the inheritance had cushioned the family for generations. Michael had been privately educated at Clifton College, Bristol’s top public school, before moving to British Airways in hopes of becoming a pilot. Grounded by poor eyesight, he had switched to ground-crew work, where he met Carole.

When the couple married in 1980 it was Middleton money that bought their first home, a Victorian semi-detached cottage in a village near Bucklebury in Berkshire – whence they moved after three years with their baby daughters Catherine and Pippa to Amman in Jordan, where Michael had been transferred. As an expat mum there was not much for Carole to do in Amman except to stage and attend parties – and this may have helped to inspire what came next. On their return to the UK in 1987, Carole, by now thirty-two, was pregnant with their third child James.

Oooh, she recalled thinking. Bills to pay!

Within months of James’s birth she had created her own trading company, Party Pieces.

It was a simple idea – a one-stop, mail-order destination from which you could order anything you needed for a children’s party. Fancy dress, candles, going-home party bags, balloons, a dinosaur table piece – Carole could source it all. She went to the Spring Fair at Birmingham in 1987, hooked up with some suppliers of paper plates and cups, stuck up a self-designed flyer at Catherine’s playgroup in Bucklebury – and began stuffing colourful party bags on her kitchen table.

There were lots of trips to the local post office in the months that followed, and business was slow to start with. These were pre-Internet days. But then Carole had the idea of advertising with a children’s book club she had subscribed to. She paid to send out ten thousand flyers, then later a hundred thousand – and orders took off. She soon had to transfer from the kitchen table to the garden shed – and then to an office space in nearby Yattendon, where her husband built the packing benches. After a year or so Mike left his job at British Airways in order to help grow the business.

‘We were pretty much the only ones doing this sort of thing when we started,’ Carole told the Telegraph in a 2018 article celebrating thirty years of successful trading. ‘It was really clear almost from the start that this was going to work … Running a business is really very simple: you buy things and sell them for a profit.’

Moderate as always, the Middletons never took major risks. Happy to bide their time, they funded their growth from revenue – and they never allowed commerce to get in the way of their parenting.

‘It was my business,’ recalled Carole, ‘so I could work around the holiday … Mike and I often talked about work in the evenings or on holiday, but we enjoyed it. I never really felt I was a working mother, although I was – and the children didn’t either. They grew up with it.’

Catherine, Pippa and James were involved from the start, often modelling for the increasingly elaborate brochures that their parents were sending out. Catherine/Kate was on the cover of one of the early Party Pieces catalogues, blowing out the candles – an image that will surely be much reproduced when she becomes Queen Catherine. As Kate grew older she styled pictures and helped to develop the business, showing a head for negotiation to match that of her mother.

‘Catherine had all the makings of a fantastic trader,’ says a business person who has dealt with Party Pieces and seen her operate at first hand. ‘Everybody thinks of her now as a mother and future queen – whatever that means. But she’s got a shrewd eye for profit and a very hard head on her shoulders. After university she worked with Party Pieces, and I am quite sure she would have taken the business into a new dimension if she had stayed – very much in her mother’s style.’

Carole Middleton’s haggling skills are legendary in the direct mail business. The family who developed today’s successful Party Pieces empire are not quite the gypsy pedlars depicted in Channel 4’s satirical TV series The Windsors, but the clan are certainly neither noble nor royal. They are a tribe of Internet stallholders at the end of the day – with a keen nose for profit.

‘Carole ran a very strong business and she ran it very well,’ says one of her suppliers. ‘But you did not want to get on the wrong side of her when it came to the pennies. Butter wouldn’t melt in her mouth most of the time, but she was a ferocious negotiator – and if the haggling wasn’t going her way, then the decibel level rose. I remember her almost screaming down the phone on one occasion when I refused to drop my price on something. People could hear her on the other side of the office – and that was in my office with her voice coming through the phone from Bucklebury, or wherever.’

Taxed on her negotiating style, Carole has ruefully acknowledged that her nickname with some is ‘Hurricane’ – but she undoubtedly got results. Within a few years Party Pieces was turning a handsome profit.

‘No one seems to have picked up on the fact that both my sister and I were millionaires before we turned thirty,’ said her younger brother, and only sibling, Gary, himself the developer of a successful UK IT recruitment enterprise. ‘She with her Party Pieces business, and me with my company.’

In fact, Carole Middleton was already thirty-two when she founded Party Pieces, but she was clearly generating a healthy cash flow by her mid-thirties. Set up as a private partnership, with related family trusts, Party Pieces has never released figures, so it is impossible to say when the family attained the millionaire status that they enjoyed by the time Kate found herself at St Andrews University with Prince William in the early 2000s. Since Kate became royal in 2011, financial analysts have had a field day probing the family company’s value – placing a £40 million estimate on the enterprise for 2020.

In August 2000 Carole is said to have forcefully negotiated the key decision that transformed her daughter’s destiny – and, indeed, the life of all the Middletons. On the seventeenth of the month, Kate’s A-level results arrived in the post – two As and a B – precisely the grades that she needed to secure her place at her first-choice university, Edinburgh, where she and two of her best friends from Marlborough College, Alice and Emilia, had long planned to study. The three girls had already travelled up to Edinburgh together to set up their lodgings.

Out in Belize, where he was on military exercise with the Welsh Guards, Prince William received similarly welcome news – he had achieved the A, B and C grades that he needed to secure his place at the University of St Andrews to study history of art the following year, and the details of his results and university destination were made public.

It was the first time the world knew that the prince was planning to study at this pleasant Scottish seaside town between Edinburgh and Dundee, starting at its highly rated, Oxbridge-level university in 2001 – and Kate promptly changed her mind about her own degree arrangements. She told Alice and Emilia that she would not be joining them in Edinburgh after all. She had decided to switch to St Andrews to study history of art, like William – and she would also take a gap year so that, if she did get a place, she would go up at the same time, and join the very same course, as the prince.

‘If’ was the operative word. The moment the news of William’s intentions became public, applications to St Andrews rocketed by 44 per cent – with many of the new applicants being female and from America.

But Kate persevered. Sometime at the end of August or the beginning of September 2000, she wrote formally to Edinburgh turning down her place through the UCAS clearing system – Marlborough had insisted she write to the university to apologise – then made a new application to join the history of art course the following year at St Andrews, all with the help of her Marlborough advisors.

‘After she left school,’ recalled her housemistress, Ann Patching, ‘Catherine made some different decisions. But why she made those decisions, I don’t know.’

A few years later the well-connected society journalist Matthew Bell presented his interpretation of Kate’s life-changing switch, based on a ‘reliable’ inside source who, according to Bell, ‘knew Kate very well’.

‘Some insiders wonder,’ wrote Bell for the Spectator on 6 August 2005, ‘whether her university meeting with Prince William can really be ascribed to coincidence. Although, at the time of making her application to universities, it was unknown where the prince was intending to go, it has been suggested that her mother persuaded Kate to reject her first choice on hearing the news.’

So the spirit of Lady Dorothy and her Silver Cross rode again, possibly in Carole Middleton, and certainly in her ambitious daughter who was willing to throw away the security of a place at Edinburgh and take her chances with St Andrews for the sake of a good history of art course – and, oh yes, the associated chance of meeting a prince and becoming ‘the top brick in the chimney’. Kate Middleton’s dramatic last-moment switch of university in August 2000 and her decision to delay her studies by twelve months would seem to display our future consort in a more ambitious and socially striving light than we have previously imagined …

Well, up to a point, Lord Copper. What is wrong with a bright and striving girl nursing the ambition to become England’s sixth Queen Catherine?

* Anglo-American editor Tina Brown cannily took The Daily Beast as the title of the online news magazine that she created in 2008 with businessman Barry Diller.

7

An Heir and a ‘Spare’

‘I felt the whole country was in labour with me.’

(Diana, Princess of Wales, Panorama, November 1995)

Diana, Princess of Wales was on Valium when she conceived her first son and sovereign-for-the-twenty-first-century, William, in the autumn of 1981 – ‘high doses of Valium,’ as she later recalled, ‘and everything else’.

So her pregnancy was a reprieve – she could come off all the drugs. ‘Thank heavens for William!’

But with the Valium-assisted future monarch came morning sickness. ‘Couldn’t sleep, didn’t eat, whole world was collapsing around me,’ she described to Andrew Morton. ‘Very very difficult pregnancy indeed … All the analysts and psychiatrists came plodding in to try and sort me out.’

The experts’ diagnosis was sympathetic, but they could hardly offer the princess a solution, since their verdict basically set out the dilemma in which this less-than-prepared twenty-year-old found herself trapped – ‘One minute I was nobody. The next minute I was Princess of Wales, mother, media toy, member of this family, you name it …’

Matters came to a head that Christmas of 1981, when the family decamped to Sandringham for what was supposed to be a holiday.

‘I threw myself down the stairs,’ Diana told Morton. ‘Charles said I was crying wolf, and I said I felt so desperate and I was crying my eyes out and he said: “I’m not going to listen. You’re always doing this to me. I’m going riding now.” So I threw myself down the stairs. The Queen comes out, absolutely horrified, shaking – she was so frightened … Charles went out riding and when he came back, you know, it was just dismissal. Total dismissal. He just carried on out of the door.’

The Prince of Wales’s behaviour reflected the advice of some of his trusted friends who had come to feel he should be tougher with what they interpreted as Diana’s self-indulgence – they felt that the princess needed to ‘pull herself together’. But Charles quickly abandoned that tactic. He could see that his young wife would not be in such misery if it were not for her extraordinary and scrutinised position bearing a future heir to the throne – ‘the demands were too great, the pressures too daunting, the loss of freedom too stifling’.

As the delivery date grew closer he spent more and more time with his wife, eventually taking her to St Mary’s, Paddington, with the dawn on 21 June 1982, and staying beside her throughout her long and painful labour which had lasted all day.

‘I felt the whole country was in labour with me,’ Diana said.

‘The arrival of our small son has been an astonishing experience,’ Charles wrote a few days later to his godmother, Patricia Brabourne, ‘and one that has meant more to me than I could ever have imagined … I am so thankful I was beside Diana’s bedside the whole time, because by the end of the day I really felt as though I’d shared deeply in the process of birth, and as a result was rewarded by seeing a small creature which belonged to us, even though he seemed to belong to everyone else as well!’

Charles was the first royal male known to be present at a birth – and it was the first time that an heir to the throne had been delivered in a hospital rather than in a royal home or palace. Tens of thousands of people had been milling outside St Mary’s all day chanting ‘We want Charlie!’ and when the prince finally emerged sometime after 10 p.m., having smartened up and straightened his regimental striped tie, the cheers were deafening. One well-wisher planted a kiss on his cheek, leaving a smudge of lipstick.

‘You’re very kind,’ the prince responded with a smile – and broke more fresh ground by lingering with the crowd informally for a chat. Asked if the baby looked like him, he replied, ‘No, he’s lucky enough not to.’ And that was the line that the Queen followed when she came to visit her grandson the next day – ‘Thank goodness he hasn’t got ears like his father.’

William was ten months old when his parents embarked on their first major foreign tour together, to Australia and New Zealand in March 1983, taking their baby son with them, to be based with his nanny at the Woomargama sheep station in New South Wales. It made for an unusual tour structure, and Buckingham Palace did not greatly approve of the couple’s breaking off from their timetable at regular intervals to fly back to Woomargama. But it brought the young family together as never before.

‘I still can’t get over our luck in finding such an ideal place,’ Charles wrote home to friends. ‘We were extremely happy there whenever we were allowed to escape. The great joy was that we were totally alone together.’

This was the moment, on the other side of the world, when William chose to start moving.

‘I must tell you that your godson couldn’t be in better form,’ wrote Charles to Lady Susan Hussey, the Queen’s great friend and lady-in-waiting. ‘Today he actually crawled for the first time. We laughed and laughed with sheer, hysterical pleasure and now we can’t stop him crawling about everywhere. They pick up the idea very quickly don’t they, when they’ve managed the first move?’

Within a week or so William was moving at ‘high speed’, reported his proud father, ‘knocking everything off the tables and causing unbelievable destruction. He will be walking before long and is the greatest possible fun. You may have seen some photographs of him recently when he performed like a true professional in front of the cameras and did everything that could be expected of him. It is really encouraging to be able to provide people with some nice jolly news for a change!’

As the future King William V performed in public for the first time, Diana made her own debut on the international scene – and it could not have come at a better moment. The royal couple had brought William along at the suggestion of Malcolm Fraser, the Liberal prime minister of Australia who had proposed the tour. But in the meantime Fraser had lost an election by a landslide to the anti-royal Labour leader Robert ‘Bob’ Hawke, who made no secret of his republican feelings – he wanted to see Australia jettison the entire outdated monarchical nonsense.

‘I don’t regard welcoming them as the most important thing I’m going to have to do in my first nine months in office,’ said the new prime minister bluntly. ‘I don’t think we will be talking about kings of Australia forever more.’

Diana soon had Hawke hauling down his flag.

‘I’d seen the crowds in Wales,’ said the photographer Jayne Fincher, recalling the enthusiasm that had greeted Diana in the principality the previous year, ‘but the crowds in Australia were incredible. We went to Sydney and wanted to photograph her with the Opera House, but just when we got there it was like the whole of Sydney had come out. It was just a sea of people … and all you could see was the top of this little pink hat bobbing along.’

In their forty flights shuttling between Australia’s six states and two territories, Charles and Diana transformed the anti-crown dynamic that had greeted their arrival. By the end of the tour an opinion poll revealed that Australian monarchists had come to outnumber republicans two to one, and even Bob Hawke had fallen under Diana’s spell. His wife, Hazel, actually found herself curtsying to the princess.

The success brought a certain uplift to the Waleses’ previously depressed marriage. As they drove together through the vast crowds in their open car, Diana regularly reached for her husband’s hand and squeezed it hard for comfort.

‘Ron, isn’t she absolutely beautiful?’ asked Charles of the AP photographer Ron Bell, as the royal couple stepped out of the lift during a reception in Melbourne. ‘I’m so proud of her.’

Crowds cheered when Diana got out of the car on their side of the street for any of the massively attended joint walkabouts – while those on the other side would groan in open disappointment at the prospect of having to put up with the prince.

‘It’s not fair, is it?’ he would grin in a sporting attempt to shrug his shoulders. ‘You’d better ask for your money back.’

It was not long, however, before the couple’s press secretary, Vic Chapman, started receiving disgruntled late-night calls from Charles complaining about his scarce column inches when compared to the acres devoted to his wife. The prince retreated into the ‘light’ reading he had brought along – Turgenev’s First Love and Jung’s Psychological Reflections. They helped him, he wrote in a letter home, ‘preserve my sanity and my faith when all is chaos, crowds, cameras, politicians, cynicism, sarcasm and intense scrutiny …

‘I do feel desperate for Diana,’ he continued. ‘There is no twitch she can make without these ghastly, and I’m quite convinced mindless, people photographing it … What has got into them all? Can’t they see further than the end of their noses and to what it is doing to her? How can anyone, let alone a 21-year-old, be expected to come out of all this obsessed and crazed attention unscathed?’

For the future head of Britain’s most significant celebrity institution, Charles displayed a curious blindness to the realities of celebrity culture.

‘Princess Superstar!’ proclaimed the headlines. ‘Without a doubt,’ declared America’s Ladies’ Home Journal, ‘she’s the greatest media personality of the decade.’ The princess, wrote one columnist, had scored ‘a humdinger of a success’ in a sceptical and potentially hostile atmosphere.

Almost single-handed, according to most commentators, Diana had saved Australia from becoming a republic – and if Charles did not get it, the young princess did. Finally she started to believe in herself.

‘When we came back from our six-week tour,’ she said later, ‘I was a different person. I was more grown up, more mature … I learned to be royal, in inverted commas, in one week.’

Britain’s left-wing Daily Mirror, not always an admirer of the monarchy, editorialised that Diana had done ‘more for the Royalty she married into than other Princesses who were born into it’.

This was a less than subtle dig by the Mirror at Diana’s sister-in-law Princess Anne, whose notorious frostiness seemed to grow a couple of degrees chillier whenever the subject of Diana came up. Aged thirty-one and a mother of two, Anne had been particularly unreceptive to the good news of William’s arrival in June 1982, which had happened while she was in the American Southwest touring Indian reservations in New Mexico on behalf of Save the Children.

‘I didn’t know she had one,’ the princess snapped when asked by one reporter about Diana’s baby.

‘Do you think everyone is making too much fuss of the baby?’ asked another.

‘Yes,’ Anne replied shortly, moving on.

‘Sweet as vinegar, cutting as a knife,’ commented William Hickey in the Daily Express.

‘Anne’s behaviour,’ said the Mirror, ‘has confirmed for many Americans the stories that she is jealous of the adoration lavished on the Princess of Wales.’

There was a certain truth to this. In the early 1980s, the hard-working Anne was carrying out over two hundred engagements every year, compared to Diana’s fifty or so – and an unimpressive ninety-plus for Charles.