Battle of Brothers

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2020

Copyright © Robert Lacey 2020

Cover image © Getty Images.com/WPA Pool/Pool/Julian Parker/PA Photos

Robert Lacey asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Extracts from Notes on a Nervous Planet by Matt Haig reproduced by permission of Canongate Books Ltd. Copyright © Matt Haig, 2018.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Source ISBN: 9780008408510

Ebook Edition © October 2020 ISBN: 9780008408527

Version: 2020-10-08

Dedication

To my brother,

Graham

– and also to my darling

Jane and Scarlett

who inspired me every day

Contents

1 Cover

2 Title Page

3 Copyright

4 Dedication

5 Contents

6 List of Illustrations

7 1 Brothers at War

8 2 Family Matters

9 3 Dynastic Marriage

10 4 Agape

11 5 ‘Whatever “in love” Means’

12 6 Party Pieces

13 7 An Heir and a ‘Spare’

14 8 Bringing Up Babies

15 9 Entitlement

16 10 Exposure

17 11 Camillagate

18 12 Uncle James

19 13 People’s Princess

20 14 Scallywag

21 15 Forget-me-not

22 16 Wobble

23 17 Kate’s Hot!

24 18 Kate’s Not!

25 19 Line of Duty

26 20 Fantasy of Salvation

27 21 White Knight

28 22 In Vogue

29 23 End of the Double Act

30 24 Different Paths

31 25 Christmas Message

32 26 Sandringham Showdown

33 27 Abbey Farewell

34 28 Social Distancing

35 Picture Section

36 Source Notes

37 Acknowledgements

38 Bibliography

39 Also by Robert Lacey

40 About the Author

41 About the Publisher

LandmarksCoverFrontmatterStart of ContentBackmatter

List of Pagesvviviixixiixiiixiv123456789101112131415161718192021222324252627282930313233343536373839404142434445464748495051525354555657585960616263646566676869707172737475767778798081828384858687888990919293949596979899100101102103104105106107108109110111112113114115116117118119120121122123124125126127128129130131132133134135136137138139140141142143144145146147148149150151152153154155156157158159160161162163164165166167168169170171172173174175176177178179180181182183184185186187188189190191192193194195196197198199200201202203204205206207208209210211212213214215216217218219220221222223224225226227228229230231232233234235236237238239240241242243244245246247248249250251252253254255256257258259260261262263264265266267268269270271272273274275276277278279280281282283284285286287288289290291292293294295296297298299300301302303304305306307308309310311312313314315316317318319320321322323324325326327328329330331332333334335336337338339340341342343344345346347348349350351352353354355356357358359360361362363364365366367369370371372373374375376377378379380381382383384385386iiiii

Illustrations

1st section

Prince and Princess of Wales at Highgrove with William and Harry, 1986 (Tim Graham Photo Library/Getty Images)

Prince Charles with Princess Anne, 1954 (Camera Press)

Prince of Wales’s wedding, 1981 (Lichfield Archive/Getty Images)

Lady Diana Spencer and Camilla Parker Bowles, 1980 (Express Newspapers/Archive Photos/Getty Images)

Prince Harry and Prince William, 1985 (Tim Graham Photo Library/Getty Images)

Princess Diana with Princes William and Harry, 1997 (John Swannell/Camera Press)

Prince Harry at Trooping the Colour, 1989 (Anwar Hussein/Getty Images)

Diana in minefield, 1997 (Tim Graham Photo Library/Getty Images)

Princess Diana presenting polo trophy to James Hewitt, 1989 (Iain Burns/Camera Press)

Princess Diana in car with Dodi Fayed, 1997 (Sipa Press/Shutterstock)

Funeral service of Princess of Wales, 1997 (Jeff J. Mitchell/AFP/Getty Images)

Funeral of Princess of Wales with flowers, 1997 (Wayne Starr/Camera Press)

2nd section

Prince William at Eton, 2000 (Anwar Hussein/WireImage/Getty Images)

Prince William and Kate Middleton at St Andrews University, 2005 (Royal/Alamy Stock Photo)

Kate Middleton on catwalk, 2002 (Malcolm Clarke/Daily Mail/Shutterstock)

Wedding of Prince William, 2011 (George Pimentel/Getty Images)

Wedding of Prince of Wales, 2005 (Hugo Burnand/Getty Images)

Duke and Duchess of Cambridge at Lindo Wing with Prince George, 2013 (Alan Chapman/Film Magic/Getty Images)

Making a Difference Together, 2018 (Goff Photos.com)

Fab Four at Sandringham, 2017 (Karen Anvil/Goff Photos.com)

Kate and Meghan at Wimbledon, 2019 (Karwai Tang/Getty Images)

Queen at Christmas, 2019 (Steve Parsons/Getty Images)

Prince William, Kate Middleton and their children at Trooping the Colour, 2019 (JS/Dana Press Photos/PA Images)

3rd section

Prince Harry in Afghanistan, 2008 (PA Photos/Topfoto)

Prince Harry in car after hospital visit, 1988 (Mirrorpix)

Princes in Botswana, 2010 (Chris Jackson/Getty Images)

Meghan and family (News Licensing)

Meghan Markle in Suits, Season 1, 2011 (Frank Ockenfels/Alamy Stock Photo)

Meghan and her mother on their way to the wedding, 2018 (Oli Scarff/AFP/Getty Images)

Prince Charles with Doria Ragland and the Duchess of Cornwall, 2018 (Jane Barlow/WPA Pool/Getty Images)

Duchess of Sussex and Queen Elizabeth II, 2018 (Samir Hussein/Samir Hussein/WireImage/Getty Images)

Meghan with women of the Hubb Community Kitchen, 2018 (Christmas Jackson/Getty Images)

Prince Harry, Meghan and their son Archie, 2019 (Dominic Lipinski-WPA Pool/Getty Images)

Meghan with Archie and Desmond Tutu, 2019 (Toby Melville/Samir Hussein/Getty Images)

Prince Harry on Abbey Road, 2020 (Samir Hussein/Getty Images)

Commonwealth Day Service, 2020 (Phil Harris/Getty Images)

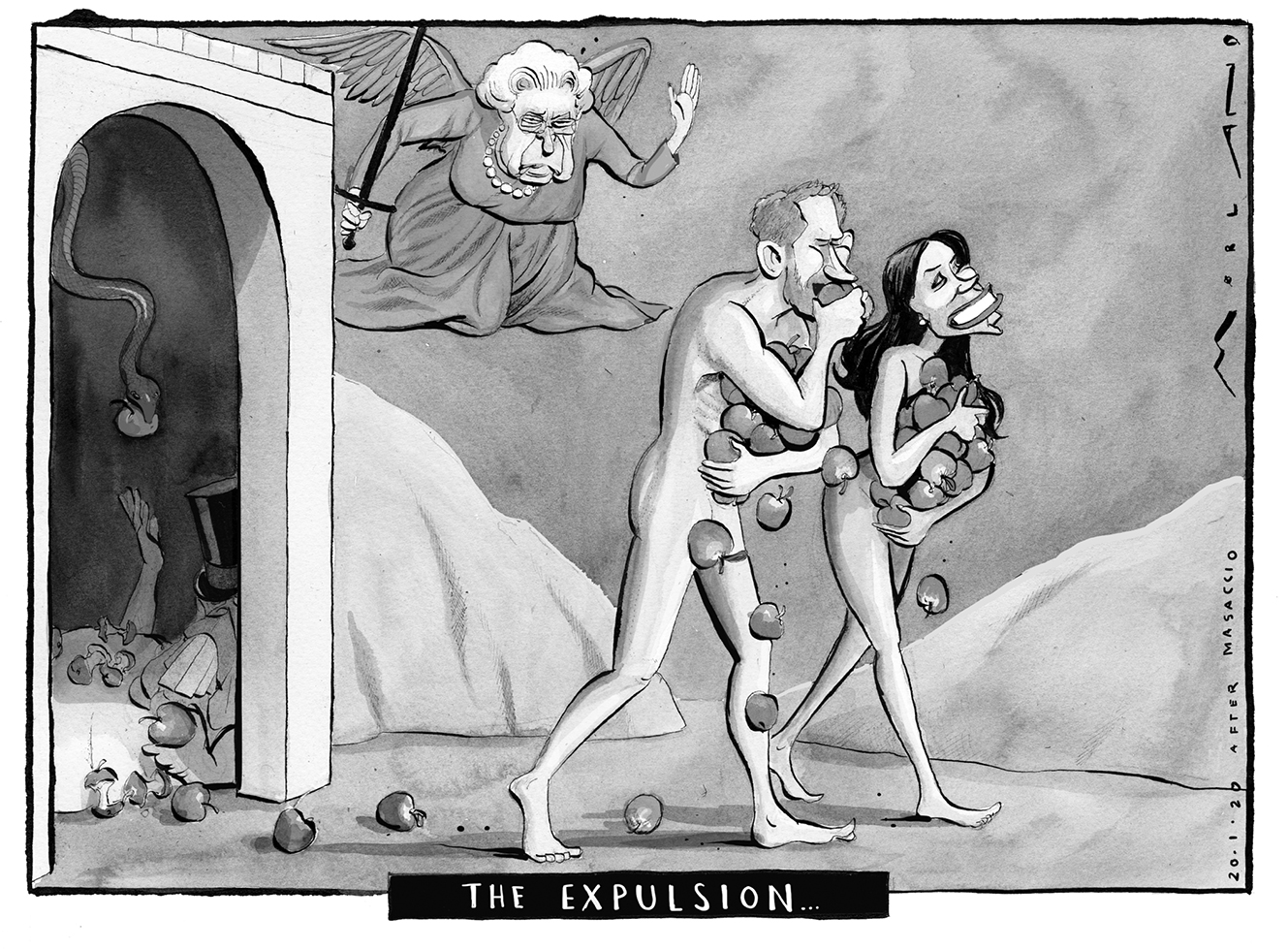

Cartoons

Harry and Meghan’s expulsion from Eden (Morten Morland/News Licensing)

The Queen writing to Roddy Llewellyn (Courtesy of the Mark Boxer Estate)

Royal infidelities featuring Charles, Camilla, Diana and James Hewitt (Mirrorpix/Reach Licensing)

Crocodile tears of the media (Chris Riddell/Guardian News & Media)

‘I’m having a ghastly nightmare’ by Cummings (Reproduced with kind permission of the Cummings family)

Fergie’s toe-licking (Tom Johnston/News Licensing)

Harry’s paternity (Ben Coppin, animator and illustrator)

Tidal wave of flowers on Diana’s death (Gerald Scarfe/News Licensing)

Diana as Queen of Hearts (Peter Brookes/News Licensing)

The Queen gives orders to James Bond (Ben Coppin, animator and illustrator)

Camilla and Charles as potted and potty (Peter Brookes/News Licensing)

Camilla and Charles ‘Gotcha!’ (Reproduced with the permission of Private Eye Magazine)

Harry in Afghanistan (Peter Brookes/News Licensing)

Queen and Philip respond to the Markles’ arrival (Peter Brookes/News Licensing)

Gallery of Prince Andrew scandal (Peter Brookes/News Licensing)

Sussex Royal commercialisation controversy (Morten Morland/News Licensing)

Harry and Meghan’s ‘Souvenir Issue’ (Reproduced with the permission of Private Eye Magazine)

Allowing the ‘Sussex Royal’ name (Peter Brookes/News Licensing)

‘He could have been the next Prince Andrew!’ (Morten Morland/News Licensing)

Harry and Meghan with zip masks (Paul Thomas/Daily Mail)

Harry and Meghan on coronavirus and the press (Morten Morland/News Licensing)

The pumpkin carriage (Peter Brookes/News Licensing)

1

Brothers at War

‘There are disagreements, obviously, as all families have, and when there are, they are big disagreements.’

(Prince William, BBC News, 19 November 2004)

Talk to each other, for God’s sake! That was the way Diana had raised her boys – to get their feelings fully out in the open in a direct fashion, not stumbling and mumbling into their emotional cups of tea like so many other members of the Windsor clan. ‘Never complain, never explain!’ – what kind of philosophy for life was that?

Thanks to their mother, William and Harry had grown up to be two expressive straight-talkers – and ambitious world-changers too. Their straight-talking – along with their attempts at changing – make up the substance of this book. And we jump into our story in May 2019 with the birth of Prince Harry’s first child and the chance that this happy event offered the two battling brothers to reconcile – to embrace and to make up. Would they take it?

There had been tiffs and troubles before, of course, in the run-up to the wedding – you know, that little wedding at Windsor Castle between the Anglo-Saxon prince and the American, mixed-race, divorcee TV star in the spring of 2018 that attracted some 1.9 billion viewers around the world. What family wedding would be complete without a few family hiccups: a disputed bridesmaid’s outfit here, a missing tiara there – and oh yes, an absentee father of the bride?

But twelve months later, almost to the day (19 May 2018 to 6 May 2019), here was the fruit of the blessed union about to arrive, a springtime baby to thrill its parents and to bring all the family back together again – especially those two Windsor brothers and their allegedly warring wives.

Royal births, like royal weddings, are the human happenings that cement the affections of a modern people to its monarchy. Constitutional historians like to explain the theory – the paradox of how a modern democracy can actually be strengthened by the elitist and undemocratic traditions of an ancient crown. But there’s nothing like the practical appeal of a newborn baby in its swaddled slumber – the fresh arrival of new life that encourages life for all.

Just as with coronations and royal weddings, a set of popular ceremonies has developed around royal births in the age of mass communications – the jostling crowd outside the hospital, the smiling parents with their baby on the steps, the shouted compliments, the flashguns exploding. Then later, the quieter, more formal christening photograph and the announcement of all the godparents’ names.

That’s how Charles and Diana set the modern style in 1982. Their son William, on 21 June that year, was the first ever heir to the British throne to be born in a regular hospital – St Mary’s in west London, right beside Paddington railway station and smelling not a little of the trains. Charles’s sister, Princess Anne, had discovered the attractions of St Mary’s private maternity wing – named after the philanthropic Portuguese-Jewish Lindo family – for the births of her children Peter (b.1977) and Zara (b.1981). Harry followed two years after William on 15 September 1984 to make up a royal quartet of Lindo births.

When William himself became a father, he and Kate adopted the same tradition, choosing Lindo for their children, George (b.2013), Charlotte (b.2015) and Louis (b.2018). By this last date the footmarks of proud royal parents displaying their newborn to the world had almost worn grooves into those stone steps at Paddington. There was an anthropological thesis to be written on the success of populist monarchies who chose to display their offspring outside railway stations at birth: Austria’s archdukes snootily kept their child production away from the public eye, and who now cared about the archdukes – in Austria or anywhere else in the world?

In May 2019, however, Harry and Meghan had decided that they did not want to display their newborn baby on those steps outside the Lindo Wing. They wanted to be royal in a new style – and maybe not royal at all. And to understand why this mattered so much, we have to go back in royal history – to the legend of the warming pan.

The warming pan was the electric blanket or rubber hot water bottle of its day, a couple of centuries back. Before his lordship retired for the night, his chambermaid would heat up his sheets by smoothing them energetically with the warming pan – a large, flat, circular brass container on the end of a long wooden handle, with a high curved lid that meant it could hold a generous quantity of red-hot coals from the fireplace. Or a newborn baby …

Such a warming pan, it was alleged, had been used in 1688 to smuggle a healthy substitute baby into the birthing bed of Mary of Modena, wife of the hated Catholic King James II, replacing the legitimate heir who was said to have been born sickly. Until 1688 the unpopular monarch had been tolerated because his successor was going to be his Protestant sister Mary and her still more Protestant Dutch husband, William of Orange. Loyal anti-Catholic Brits had hoped that the generally popular and non-popish couple would succeed the childless and far-too-popish James as joint monarchs, William-and-Mary, thus preserving what passed for democracy in those days – as well as the Church of England.

The unexpected appearance of the living and healthy ‘warming pan’ baby, James Francis Edward Stuart, however, threatened this scheme – and 1688 turned into a landmark year in the history of Britain’s monarchy. William of Orange sailed his invasion fleet into Torbay that November, bloodlessly persuading James II to flee London with his warming pan son.

The ‘Glorious Revolution’ was British history’s memorable moniker for the stirring events of 1688 and its resulting settlement that became the model for our modern system of enhanced and democratic powers for Parliament and reduced powers for an increasingly symbolic ‘constitutional’ monarchy. Alongside the theoretical changes came the very practical provision that all royal births must, in future, be personally attended by the home secretary of the day, whose job it would be to make sure that the new royal arrival had been delivered properly, and not in a warming pan.

So, well into modern times, attendance beside the royal birthing bed became the duty of every British home secretary. Queen Victoria gave birth to all nine of her children with her home secretary in the room, along with assorted privy councillors – and this intrusive custom lasted long into the twentieth century. Sir William Joynson-Hicks was present at the birth of the future Queen Elizabeth II at her parents’ London townhouse in April 1926, and, four years later, his Labour successor, John Robert Clynes, had to travel up to Glamis Castle in Scotland to be at the birth of her sister Margaret – he found himself stranded there with a single, operator-controlled telephone line for two whole weeks because the princess arrived late.

In November 1948 Prince Charles became the first post-1688 heir to the British throne to be born without the ritualised scrutiny of his arrival on behalf of the people. Clement Attlee’s post-war Labour government had wasted no time in sweeping away the outdated practice. But Charles revived its spirit in 1982 and 1984 with the births of William and Harry, when he and Diana proudly – and dutifully – brought their sons out onto the steps of the Lindo Wing for public inspection and approval, within hours of their births.

Prince William continued the tradition unquestioningly – though by 2013 the performance had turned into a menacing and undignified scrum among the ever-growing mass of paparazzi, in a most alarming free-for-all. But William still did his duty sturdily, beside him Kate, immaculate and smiling despite the traumas of delivery. As an heir to the throne who had done his homework, Prince William knew about warming pans and the importance of making the people feel that you were at one with them.

But as the ‘spare’, his younger brother had received no such special instruction in the ancient legend, let alone its sociological importance – and if he had, Harry could not have cared less. The heir could choose to suffer the ordeal of inspection on the Paddington steps if he wished. The spare had other ideas, and his wife totally agreed. Harry and Meghan were resolute that their newborn baby’s first sight of the world should not be the same insane and lethal camera-flashings that had attended – had actually brought about – the death of Diana.

A cursory glance at the photograph of baby Harry in his mother’s arms outside the Lindo Wing in September 1984 also suggested that Diana must have spent a good hour or more washing and blow-drying her hair before she emerged onto the steps for her ‘spontaneous’ greeting of the people. Cautious Kate might put up with all that primping and prepping for the sake of ‘the Firm’, but mercurial Meghan would not.

So Harry and Meghan, the Duke and Duchess of Sussex, had agreed that their new child should be delivered at home in the peace and seclusion of Frogmore ‘Cottage’ – not so much a cottage, in fact, as a collection of cottages in Windsor Great Park that had recently been renovated and amalgamated into a long, twenty-three-room dwelling at a cost of some £2.4 million in public funds. Here was another mildly difficult issue. If the royal parents were not going to display their baby to the public for the sake of warming pans, what about all those pots and pans and cooker(s) in their lovely new kitchen? Perhaps some public gesture would be appreciated to say thank you for all that taxpayers’ money?

As events turned out, the question would be academic. Baby Sussex took his time a’coming, and when his expected arrival became two weeks late Meghan’s doctor (a secret, whose name has not been revealed to this day) advised a hospital-assisted delivery. Frimley Park was a perfectly good NHS hospital a dozen miles down the road near Farnborough, but the couple set off instead with Meghan’s mother Doria on the longer journey to London and Britain’s most expensive delivery facility, the US-owned Portland Hospital, famous for its celebrity births. Victoria Beckham, Liz Hurley, Kate Winslet – all these glamorous mothers had delivered their babies in the luxury of the Portland, where a basic birth package starts at £6,100, with four-poster cots for the babies. And not a nasty, smelly railway station in sight.

Here was another issue with Harry and Meghan – the deluxe, five-star instincts to which these reach-out-and-touch-me tribunes of the common people so regularly surrendered, from their fondness for private jets and Hollywood friends to their need to ‘hide away’ in expensively renovated twenty-three-room ‘cottages’ or, when they first moved to California in 2020, an $18 million, twelve-bathroom Tuscan-style mansion occupying twenty-two acres in Los Angeles’ exclusive Beverly Ridge Estates.

‘It’s a matter of security,’ their handlers would explain. ‘And they DO need their privacy.’

But the Portland Hospital did its job efficiently and confidentially through the night of 5 May 2019. On the morning of 6 May, Meghan was duly delivered of her delayed but healthy son, weighing in at 7lbs 3oz. Baby Archie had arrived with the dawn at 5.26 a.m., allowing grandmother Doria and the happy couple to return to Windsor with their precious cargo undetected. Their stratagem was bolstered by Buckingham Palace’s putting out a strangely misleading statement at 2 p.m. that day saying that the Duchess of Sussex was just going into labour – when she had, in fact, been delivered of her new son eight hours earlier.

Harry and Meghan had played fast and loose with both royal tradition and the truth, but for once they had successfully outwitted the hated press.

2

Family Matters

‘He is the one person on this earth that I can actually talk to about anything and we understand each other.’

(Prince Harry, January 2006)

The helpful ‘friends’ who brief the media from time to time about the inner thoughts of royal folk have let it be known that elder brother William did not think too highly of Harry and Meghan’s ‘prima donna’ manoeuvres to conceal the birth of their son in May 2019 – and this impression was confirmed by the failure of William and Kate to visit the new arrival for a full eight days. By contrast, the Queen, Prince Philip, Charles and Camilla all turned up within hours to coo over the baby – and it seemed strange that, when the Cambridges did finally pitch up more than a week later, they didn’t bring along little George, Charlotte and Louis to welcome their new cousin.

But Harry won the next round. On 8 May he had appeared with Meghan cradling the two-day-old Archie Harrison Mountbatten-Windsor in the soaring and magnificent surroundings of St George’s Hall, Windsor, with the press pack excluded. There was just a single photographer of their choice and a small group of TV cameras with whom they spoke of their joy.

‘It’s magic, it’s pretty amazing,’ declared Meghan. ‘I have the two best guys in the world, so I’m really happy.’

‘He has the sweetest temperament,’ disclosed Harry. ‘He’s really calm. I don’t know who he gets that from!’

The name ‘Archie’ was said by Sandhurst mates to have been inspired by a mentor of Harry’s in the army – Major Tom Archer-Burton – while the baby’s mother offered a posher clarification. ‘Arche’, the Duchess of Sussex explained, was a term from classical Greek meaning ‘origin’ or ‘source of action’ – Meghan had picked up more classical learning at school in Los Angeles than ever Harry had at Eton – and the couple would later bestow the same name on their charitable foundation. As for Harrison, well, that was sort of a joke – ‘Harry’s son’ – leading some commentators to wonder if the name had anything to do with the mystic and meditational aura of George Harrison, Meghan’s particular idol in the Beatles.