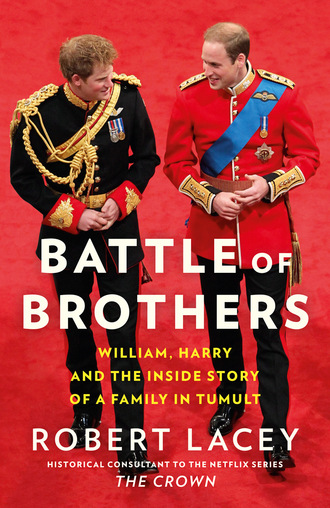

Battle of Brothers

Swaddled in a white blanket and wearing a delicate white knitted hat, little Archie appeared to sleep peacefully throughout his first official photo call – which was, of course, exactly as his father and mother had planned it.

‘Thank you, everybody,’ said Meghan, ‘for all the well wishes and kindness. It just means so much.’

The entire private-public occasion was just pitch-perfect – with the splendid lofted windows of St George’s providing the ideal backdrop – a touch of history along with modernity: it was Harry the father who, fifty-fifty parenting style, was cradling the baby, not the mother, unlike every previous photograph on those wretched Paddington steps.

And then came an even warmer family occasion when the proud parents were shown presenting Archie to the Queen, Prince Philip and Doria. The picture made the front page of every British newspaper – and a good many others around the world – with the two grandmothers, black and white, smiling down on the British monarchy’s first mixed-race baby.

‘How any woman does what they do is beyond comprehension,’ remarked Harry in one of his post-birth interviews. ‘It’s been the most amazing experience I could ever have possibly imagined.’

But here came the real crunch: the godparents. An essential component of any Church of England christening process, these adult mentors who will guide the new baby spiritually, morally and often materially through life are considered even more important for members of the royal family. Technically, they carry the title of ‘sponsor’.

Numbers six and seven in the order of succession may not seem particularly close to inheriting the crown, but who knows what can happen in an age of mass terrorist attack and global pandemics. Six and seven could well get promoted to three and four – or even higher. And, more profoundly, anyone in the single figures – Harry stands at six at the time of writing, Archie at seven – is certainly ‘royal’ whether they like it or not, since they have been sanctified by the public’s emotional commitment to them, as well as by taxpayers’ largesse.

It is well understood at Buckingham Palace that not all godparents can make it to a hastily arranged christening service. So in July 2019, Elizabeth II’s Holyrood Week duties in Scotland meant that she and Prince Philip could not attend the ceremony for Archie on 6 July. And this date had already been the result of some shuffling of schedules to accommodate the busy summer diaries of Charles, Camilla, William and Kate – not to mention the Archbishop of Canterbury who was to preside over the rite.

Yet it is still expected by monarch, palace and just about anyone with a stake in the game that the world should be told who the new royal baby’s ‘sponsors’ are. How can you judge the suitability of a sponsor who remains unknown? ‘Secret sponsor’ has a dodgy sound to it. And it is an ingredient of Britain’s representative monarchy that Brits should have the right to know who is giving moral guidance to their possible future king or queen. Here again, however, precedent, protocol and practice all collided headlong with Harry and Meghan’s firm insistence on their privacy – and that of their new baby.

‘Archie Harrison Mountbatten-Windsor will be christened in a small private ceremony by the Archbishop of Canterbury in the Private Chapel at Windsor Castle on Saturday 6th July,’ announced Buckingham Palace in a statement on 3 July. ‘The Duke and Duchess of Sussex look forward to sharing some images taken on the day by photographer Chris Allerton. The [names of the] godparents, in keeping with their wishes, will remain private.’

Confirming the palace announcement, the Sussex Royal office made clear that the whole ‘sponsor’ issue was non-negotiable. The godparents’ names would not be revealed.

‘I’ve covered five or six christenings in my royal career,’ commented Majesty magazine’s editor-in-chief Ingrid Seward on the Today programme. ‘And I’ve never come across such secrecy.’

Was brother William outraged? Just angry? Or merely perplexed?

‘Friends’ tried to keep the temperature down by suggesting the last – that the future king, only five places clear of Archie in the order of succession, could not comprehend how such a basic matter of constitutional principle had been misunderstood. How could any new Windsor royal be christened in a meaningful sense without the newcomer’s sponsors being known, if not present?

William was smiling after a fashion on the morning of Saturday, 6 July, when he turned up for his nephew Archie’s christening in the Queen’s Private Chapel at Windsor, and the family photograph that would follow in the formality of the Green Drawing Room. But it was a wry and curious smile, and commentators had a field day interpreting what the prince’s face and posture – and those of his wife – might portend. Kate was thoughtfully wearing a pair of her late mother-in-law’s pearl drop earrings – the very pair that Diana was said to have worn to Harry’s christening in 1984. Yet Kate was sitting rather ‘awkwardly upright’, thought body language expert Judi James. The duchess was leaning forward in a ‘ready to flee’ posture.

This was nothing, however, when compared to Ms James’s verdict on William, standing to attention behind his wife with a ‘fig leaf hand clasp’ shielding his trouser crotch, in her opinion, and a ‘raised chin pose that a policeman might adopt before collaring a suspect’.

A few Internet commentators agreed. ‘William looks like he would rather be elsewhere,’ tweeted one, with another ‘royal fan’ responding, ‘William should have a much bigger smile on his face.’

Oh, the lot of a future king! Was this the captious and carping destiny for which Prince William, second in line to the throne, had been working for over twenty years since his visits to Windsor Castle for lunch with his grandmother the Queen in the late 1990s? Aged thirteen in the autumn of 1995, the prince had just started school at Eton College, the exclusive all-male academy (founded 1440) across the Thames from Windsor.

It was then three years after his parents’ separation – just two years before Diana’s death – and the Queen was worried about her grandson’s state of mind. Was Charles too wrapped up in his own concerns to be a proper father, with that Camilla Parker Bowles and everything else in the picture? While Diana, of course, with her motley succession of largely foreign boyfriends, was deliberately acting as a subversive anti-royal ‘flake’. The Queen actually feared that the boy might be heading for some sort of breakdown, she confided to one of her advisors – just as the prince’s mother herself had clearly cracked up mentally in several respects.

The Duke of Edinburgh intervened. Philip shared his wife’s concerns and he suggested that she overcome her longstanding aversion to involvement in messy family matters by trying to get closer to this particular boy – who was not just her fragile grandson, but a future inheritor of her crown. Perhaps the lad could come up and join them both in the castle from time to time on a Sunday, when the Eton boys were allowed out into the town?

And so the lunches had begun. Every few Sundays – allowing for the weekends that William would spend with his separated mother or father – the teenager would walk along Eton High Street with his detective, and across the bridge up to Windsor, where he would join the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh for a hearty and tasty meal.

Pudding ended, Philip would make a discreet exit, leaving his wife and grandson together in the panelled Oak Room with its six-arm chandelier hanging over the table in front of Queen Victoria’s beautiful Gobelins tapestry of The Hunt. In this splendid and historic but also intimate setting, grandmother and grandson – monarch and future heir – would get down to brass tacks, talking and ‘sharing’ as only the pair of them could.

‘There’s a serenity about her,’ William revealed ten years later, talking to the Queen’s 2011 biographer Robert Hardman, and explaining how his grandmother had encouraged him to stay calm in the face of all that the world would throw at him one day. ‘I think if you are of an age, you have a pretty old-fashioned faith, you do your best every day and say your prayers every night. Well, if you’re criticised for it, you’re not going to get much better whatever you do. What’s the point of worrying?’

It was during these conversations in the Oak Room that Prince William learned from his grandmother how the institution of the crown was something to be upheld and respected, and how one might have to fight – he might have to become quite tough, in fact – in order to preserve it. It was William’s birthright and legacy, after all, as much as his gran’s. The prince was particularly impressed by the stories that his grandmother would tell him about her own early years on the throne – how she had had to step in to succeed her father King George VI in 1952, at the age of only twenty-five, to tackle a job that many men in those days believed they could do better.

‘It must have been very daunting,’ he said to Hardman. ‘And I think how loads of twenty-five-year-olds – myself, my brother and lots of people included – didn’t have anything like that. And we didn’t have the extra pressure put on us at that age. It’s amazing that she didn’t crack. She just carried on and kept going. And that’s the thing about her. You present a challenge in front of her and she’ll climb it. And I think that to be doing that for sixty years – it’s incredible.’

Talking to the BBC in 2005, as he neared the end of his studies at St Andrews University, William would again pay tribute to the personal support and advice that his grandmother gave him.

‘She’s just very helpful on any sort of difficulties or problems I might be having,’ he said. ‘She’s been brilliant, she’s a real role model.’

It was in the Oak Room conversations that William would have heard of warming pans and the Glorious Revolution, along with the role that the armed services would have to play in his future. Then there was the importance of the Church of England in his responsibilities as monarch – though none of this was presented to him in any formal, lecturing sort of way.

‘I don’t think she believes too heavily in instruction,’ he said in 2016, expanding to the BBC on the subject of the Queen’s personal style and input, which he described as ‘more of a soft, influencing, modest kind of guidance’.

The Queen herself had received formal constitutional history lessons. In a curious mirror image of William, the young Princess Elizabeth used to walk over the Thames between Eton and Windsor twice a week in the months before the Second World War, when she was thirteen – but in the opposite direction. Accompanied by her nanny Marion Crawford (‘Crawfie’), the princess had gone for history tutorials to the book-littered study of Sir Henry Marten, the Vice-Provost of Eton, an eccentric scholar whose habit, while ruminating, was to crunch on sugar lumps that he shared with his pet raven.

One of Sir Henry’s particular enthusiasms had been the recent creation of the British Commonwealth of Nations, formalised by the Statute of Westminster of 1931, and the ingenious arrangement by which the Commonwealth contained at that date more than half a dozen monarchies – Canada and Australia, for example. There Elizabeth’s father George VI did not reign as some remote imperial sovereign in London, but as Canada’s or Australia’s very own king and head of state.

Elizabeth II was particularly proud of having developed and built upon this decentralised system in the course of her reign – by the year 2000 there were no fewer than fourteen Commonwealth monarchies around the world – and she passed on to William the importance of maintaining Britain’s Commonwealth links, especially in Africa, the Pacific, the Caribbean, the Indian subcontinent and other developing corners of the globe. And all this, of course, came on top of the challenge to the young man of having to prove himself one day as a dignified and respected – but not too posh and remote – truly ‘representative’ monarch of the United Kingdom at home to the satisfaction of the fractious Brits.

As William absorbed his grandmother’s principles, there was a sense, he later described, in which he became as one with her, establishing a warm personal closeness – a strong and quite extraordinary partnership across the generations that he defined as a ‘shared understanding of what’s needed’.

The prince’s conversations in the Oak Room helped to turn the fragile schoolboy heading for a breakdown into quite a tough young man who would once be compared to a ‘nightclub bouncer’ protecting the standards of and entry to his highly exclusive royal club. The prince was not prepared to allow anyone – and certainly not his brother and his American celebrity wife – to threaten the precious legacy that had been entrusted to him by his gran.

‘She cares not for celebrity, that’s for sure,’ William declared in 2011. ‘That’s not what monarchy’s about. It’s about setting examples. It’s about doing one’s duty, as she would say. It’s about using your position for the good. It’s about serving the country – and that’s really the crux of it.’

Brother Harry might be heading for La-La Land, but brother William was heading to be king.

‘I’ve put my arm round his shoulder all our lives together,’ said the prince to a friend, explaining why Harry and Meghan’s behaviour and the succession of erratic decisions surrounding Archie’s birth and christening – particularly the weird concealing of the godparents – had led to the rupture between the brothers that Harry would describe later that year as the pursuit of ‘different paths’.

‘I can’t do it any more,’ said William.

The identity of those ‘secret’ godparents, of course, did not stay secret for very long. Secrets will out, and the names of Archie’s three British sponsors became public within months of his christening.

Tiggy Pettifer, née Legge-Bourke, had been the beloved nanny of both William and Harry. Mark Dyer had played a similarly formative role in the lives of the young princes – ‘a former equerry to the Prince of Wales’, as The Times described him, ‘who became a mentor and close friend to Charles’ sons’. Then there was Charlie van Straubenzee, one of Harry’s closest childhood friends and Eton schoolmates. Meghan and Harry had attended his wedding in August 2018.

A combination of newspaper digging and high society contacts got these three British names on the record by the end of 2019, and, once out there, the names were not denied by Buckingham Palace, the Sussex Royal office, nor the godparents themselves. The question was – who were the others? The three British names clearly represented Harry’s choices of sponsor. So the focus turned upon whom Meghan might have chosen.

If there were three British sponsors, logic suggested there must be one, two or three American sponsors. And the three US names on whom speculation, informed or otherwise, centred were tennis star Serena Williams, film star George Clooney and one or other of the political star couple, ex-President Barack and Michelle Obama. All four were friends of Meghan, who had gone to watch Serena at Wimbledon in the summer of 2019, while George Clooney had already cheerily dismissed the rumours in a cleverly crafted non-denial denial.

‘You don’t want me to be a godparent of anybody,’ Clooney said at the time of Archie’s birth. ‘I’m barely a parent at this point. It’s frightening.’

When it came to the Obamas, the husband and wife team were close to both Meghan and Harry. Barack Obama had joined the prince in Toronto in 2017 at the Invictus Games for injured ex-servicemen and women – Harry’s own creation and one of his most dearly cherished causes – while Michelle had written an article for the UK issue of Vogue that Meghan had guest-edited in September 2019 – see Chapter 22 for more on that. Certain American commentators even wondered whether the Obamas were not encouraging the new duchess to pick up their liberal political legacy at some time in the future – on the way to Meghan achieving her teenage ambition to give the United States its first mixed-race female president.

Such fanciful imaginings showed what can happen when you seek to divert the truth from its natural course – and the course of this book is to seek to reveal the truth. The pages that follow will narrate the story of two brave young men who have lived through extraordinary privilege and tragedy, each of them challenged from birth by their ultimately different destinies. For many years, the two brothers would work together, supporting each other in times of trouble. But as time and circumstance have changed, so William and Harry have, inevitably, grown in different directions.

In recent months – even as this book was being written – we saw the younger of the pair finding himself a new identity and seeking to follow, with his wife, a new way ahead. In Shakespearean terms, Prince Harry has decided to throw off his old and troubled past – the dissolute world of Falstaff and Prince Hal – to remake himself in the fresh and shining role of King Henry V, British history’s heroic and exemplary monarch: ‘Oh, happy band! Oh, band of brothers …’

The trouble is that brother William has claimed that job already.

3

Dynastic Marriage

‘Marriage is a much more important business than falling in love …’

(Prince Charles, 1979)

So you are approaching the age of thirty. You are a single male of the species – reasonably attractive if rather shy, and not very sexy. You are heir to the throne of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland – plus Canada, Australia, New Zealand and a dozen or so other Commonwealth monarchies – and you have your love life to organise.

No, sorry, you have a future queen to locate for this formidable array of thrones.

Is there a difference?

Well, yes, there is, actually – and that dilemma provides the basis of the story that is at the heart of this book. Princes William and Harry were the products of an arranged dynastic alliance, not a love match …

As the future King Charles III responded to the nudgings of his family in the late 1970s to get on with the business of tracking down a lifetime companion, the Prince of Wales found himself on the horns of a dilemma – to which his great-uncle and ‘honorary grandfather’, Lord Mountbatten, had a solution that he would reiterate with relish:

‘I believe, in a case like yours,’ wrote Mountbatten to Charles on Valentine’s Day, 1974, ‘that a man should sow his wild oats and have as many affairs as he can before settling down. But for a wife he should choose a suitable, attractive, and sweet-charactered girl before she has met anyone else she might fall for.’

It was a measure of Charles’s shyness that he did not tell his interfering ‘Uncle Dickie’ to stuff his cynical advice where the monkey puts his nuts, since his ‘honorary grandfather’ was not only peddling the values of a vanished age, he was also pushing the candidacy of his own granddaughter, Amanda Knatchbull, just sixteen, as the ‘suitable, attractive, and sweet-charactered girl’ whom Charles should eventually select as his future queen – thus bringing even more Mountbatten blood into the dynasty of Windsor.

Nine years his junior, Amanda knew the prince well, and in time she would come genuinely to love Charles, in her grandfather’s opinion. But as a teenager she was clearly too young to commit to marriage – so the old man’s worldly counsel was offered in the hope that his great-nephew would ‘keep’ himself for Amanda.

‘I am sure,’ Charles responded a few weeks later, ‘that she must know that I am very fond of her …’

In the event, Charles’s and Mountbatten’s imaginative ambitions for Amanda Knatchbull – discussed in her total absence and ignorance – came to naught. Over the years the two cousins did grow close, developing a mutual respect and friendship that has lasted to the present day. But when the prince finally made his proposal in the summer of 1979 – shortly before Lord Mountbatten’s assassination by the IRA – the independent-minded Amanda politely turned him down.

‘The surrender of self to a system,’ she explained, was so absolute when joining the royal family, it involved a loss of independence ‘far greater than matrimony usually invites’.

These powerful if formal words come to us via the memory of Prince Charles, as he recounted the details of his rejection to his biographer Jonathan Dimbleby. The prince could recall every reason Amanda had given him for her refusal – and especially ‘the exposure to publicity, an intrusion more pervasive than attends any other public figure except at the zenith of a chosen career’.

‘Her response,’ concluded Dimbleby, ‘served only to confirm his own belief that to marry into the House of Windsor was a sacrifice that no-one should be expected to make.’

The future king would clearly have to find himself another suitable and sweet-charactered girl. But in the meantime, Charles had enjoyed several years of success pursuing Uncle Dickie’s alternative line of advice on the sowing of wild oats, since he had made the acquaintance of a certain Camilla Parker Bowles (née Shand), a characterful lady noted for her sheer brass nerve. Long before her royal future was assured, Mrs Parker Bowles had taken her young children, Laura and Tom, shopping to Sainsbury’s in the Wiltshire market town of Chippenham.

‘Most of the parking spaces were filled,’ recalled Laura, ‘but Mummy saw an empty one right outside the front door and nipped in there. The parking space was “Reserved for the Mayor of Chippenham”.’

When the family came out with their shopping bags, a man stopped Camilla and asked her what she was doing in the mayor’s parking place.

‘Mummy smiled and said, “I’m so sorry, I’m the Mayor’s wife …” and hurried me into the car. The man followed us and said, “What a joy to meet you for the first time – I’m the Mayor!”’

The story gives credence to the scarcely believable tale of how Camilla is often said to have first introduced herself to Charles, sometime in the early 1970s. It was a pouring wet afternoon and the prince, aged twenty-two, was just stroking one of his ponies after a polo match on Smith’s Lawn in Windsor Great Park, when Camilla Shand, then twenty-four, approached for a chat – without any introduction.

‘That’s a fine animal, sir,’ she said. ‘I’m Camilla Shand.’

‘I’m so pleased to meet you,’ replied Charles politely – only for Camilla to dive straight in with a reference to her ancestor, the notorious Alice Keppel, mistress of King Edward VII.

‘You know, sir, my great-grandmother was the mistress of your great-great-grandfather – so how about it?’

This extraordinary tale puts the mayor of Chippenham to shame, and many of the prince’s biographers have questioned its reliability. Charles himself, via his semi-official biographer Dimbleby, is quite clear that although he did meet Camilla at the polo from time to time, he first met her properly in London, through his former girlfriend Lucia Santa Cruz, the Chilean research assistant of Lord Butler, who was the master of Trinity, Charles’s college at Cambridge.

Before he became master of Cambridge’s largest and poshest college, Richard Austen Butler, universally known after his initials as ‘Rab’, was a Tory grandee who had occupied numerous Cabinet ranks. But for all his record of public achievement, Rab’s fondest private boast was how he had used the Trinity Master’s Lodge to facilitate the liaison by which a ‘young South American had instructed an innocent Prince in the consummation of physical love’. In 1978 Butler indiscreetly told the author Anthony Holden, who was writing a semi-authorised biography of Prince Charles, that he had ‘slipped’ Lucia Santa Cruz a key to the Master’s Lodge, after Charles had asked if the young lady could stay there with him ‘for privacy’.

When Holden’s book was published in 1979, Buckingham Palace indignantly denied Rab’s suggestion that Lucia had initiated Charles into the delights of the sexual dimension.